Biljana Đurđević, Present State. Courtesy of the October Salon.

Biljana Đurđević, Present State. Courtesy of the October Salon. A significant question posed by this year's October Salon in Belgrade—What's Left?—sparked many theoretical and artistic reflections. As the show and its accompanying events demonstrated, it delved into the future and significance of art and the relevance of large international exhibitions in today's world. With the Salon now closed and its next iteration anticipated in two years, revisiting selected works offers a compelling insight into one of its thematic undercurrents that, though not particularly emphasized within the three curatorial frameworks—Hope is a Discipline, Traces, and Aesthetic(s) of Encounter(s)—provides an insightful lens into contemporary art and its trajectories.

"Everyone is afraid, but art can help us process the fear. Art also has the power to transform. Artists are letting their creativity flow, as a tool for survival, now more than ever!" states Barbara Klein in her text Art in the Time of Crisis. Cited by artist and October Salon Board member Mihael Milunović in his short commentary for the Salon's catalogue, the quote can be taken to encompass various artistic and global concerns—especially in light of current ecological crises that have led to significant loss of life in recent months—while allowing art a position of a political agent capable of activating processes of change. The fear Klein mentions, especially in this context, has preoccupied artists for several decades, escalating in recent years with the surge of eco art and the prominence of environmental issues in contemporary art practices and theory.

In the rich selection of works at the Salon, those addressing concerns regarding ecology and the destruction of natural habitats, nature-human relations, and anthropocentrism presented their propositions and critiques both directly and implicitly, including also examinations of direct and immediately visible consequences of intersections of environmental and socio-political issues.

Among the most direct yet poetic examples was a video work by Anne Imhof, who represented Germany at the 2017 Venice Biennale and won the Golden Lion for the best national pavilion. Imhof's Youth (2022), shown in the dark basement of the Salon of the Belgrade City Museum, featured a group of wild horses that roam freely through a snowy landscape—the Chertanovo Severnoye district on the outskirts of Moscow, Russia.

The bleakness of the washed-out landscape that, at times, revealed a concrete housing block that appeared deserted contrasted sharply with the vigorous movements of the horses against the resonant soundtrack of Bach's St. Matthew Passion. The imagery's symbolism betrays deeper concerns with the human-nature relationship, as hinted at by the artist herself, who commented that the inspiration for the piece came from the wild horses that roam the exclusion zone near Chernobyl, a site of the biggest nuclear catastrophe in Europe.

The unstoppable natural forces set free in the wintry landscape the humanity's controlling hand failed to capture, exist in an uncertain chronotope: it might be a post-apocalyptic world recuperating after human-made devastation, or the present moment when the vision of harmonious coexistence among species remains an elusive dream.

Another nook of the same basement featured Edi Dubien's watercolours on paper portraying the human body in a symbiotic relationship with nature. "I've never met nature, I am nature," said the artist, whose delicate drawing depict human figures from which plants sprout, reflect on the skin, or heads metamorphose into animals. This profound connection to nature is further underlined in Dubien's statement, where he notes that he "recognized himself in the morning mists around the forests where deer and fox hide, I recognized myself in the wind…"

Cross-species symbiosis has been one of the dominant themes in recent eco art focused on alternative modalities of existence and sympathetic and mutually beneficial relationship between species. In these considerations, our environment and nature are no longer objectified; rather, they are expanded to include a "'multitude of ecologies'—biological, technological, political, social," as art historian T.J. Demos pointed out.

The new environments are not to be mastered, ruled over, or tamed—an attitude towards the 'other' deriving from colonial and imperialist epistemologies—but embraced in their multiplicities in which humans are just another part, equal to others in their ontological status.

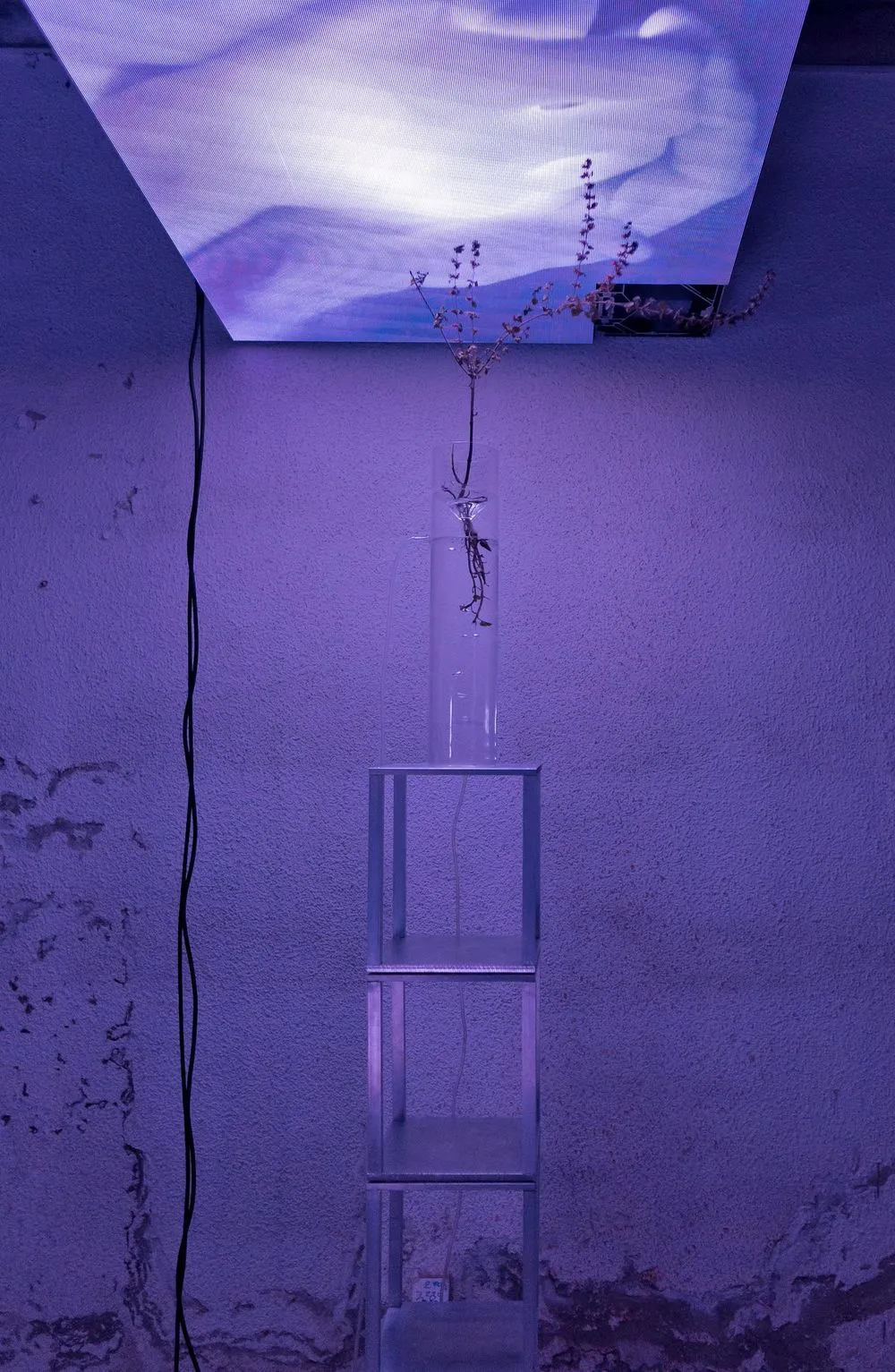

One such symbiotic relationship was explored in the work by Jesper Just titled Seminarium (plant nursery). It comprised a complex system of cables, glass vases, tubes, LED screens, and plants, creating an unexpected symbiosis between human digital presence and the natural world in the dark basement space. The violet light emanating from the screens showing human bodies sustained the plants in vases, which, in turn, could be used as food or medicine by humans—their survival is intricately linked.

The work highlighted the interconnectedness between different species and technology, bridging the fissures built by previous social structures. Here, nature was not an object upon which human power is asserted but is instead looped in with other elements that constitute our environment, across a spectrum of positions and concerns.

While environmental and ecological issues affect different communities globally, the consequences of climate change, loss of arid land and jobs, and other related factors manifest themselves across the spectrum of human conditions. Issues such as lack of housing, forced migration, and other social challenges wave a complex narrative of capitalist exploitation and its devastating consequences, where environmental factors are only one aspect.

Forced to move due to economic or ecological hardships—or a combination of the two, which has become a dominant structural factor across vast regions of the globe—people face various forms of marginalization, exploitation, and oppression, intersecting with different aspects of their identities.

The works addressing these problems at the Salon included those by Biljana Đurđević, whose painting Present State showed a bleak collective living environment of labourers; Malek Gnaoui's audio-visual installation Firnas, which often explored perilous migratory travels from Tunisia to Europe; and Milica Ružičić, whose photo series Hope= Home brought together the most advanced technology and people living on the margins of techno-capitalism.

Whether these works can function as aesthetic agents for a new era beyond anthropocentrism and whether they will help usher in new positionalities on the human-nature axis will depend on the answer to the Salon's question: what's left? An answer that could lie in the remnants of the big exhibitions and works presented, in forms of ethics, hope, community, and collectivity they foster and preserve.