Algernon Miller, 11.11 The Future Lives in the Past, 2022

Algernon Miller, 11.11 The Future Lives in the Past, 2022 I first encountered Algernon Miller as the architect of Frederick Douglass Circle, the great circle that demarcates the northwest corner of Central Park. I walked, biked, and drove that plaza hundreds of times when I lived just off Cathedral Parkway: I even sold a man my old pair of AirPods on the plaza in a Facebook marketplace deal, which felt a little wrong. Because unlike its counterpoint to the south, Columbus Circle, Frederick Douglass isn't flanked my malls and Whole Foods. It has an air of the sacred—the feeling of a gateway to a new and different place than you came from.

Harlem's history as the pulsing heart of Black liberation and culture in New York needs no reintroduction here. And it's hard to imagine a figure more immersed in and of the American cultural revolution that occurred here, notably post-Harlem Renaissance, than Miller. Born in Harlem in 1945, he would go on to study at The New School and SVA with the aid of prestigious scholarships, and blend uptown and downtown beats both in his life and art. A small survey of his work was exhibited by Ethan Cohen Gallery, alongside contemporaries like Ellsworth Ausby, Nanette Carter, and Joe Overstreet under the title AFROFUTURISM.

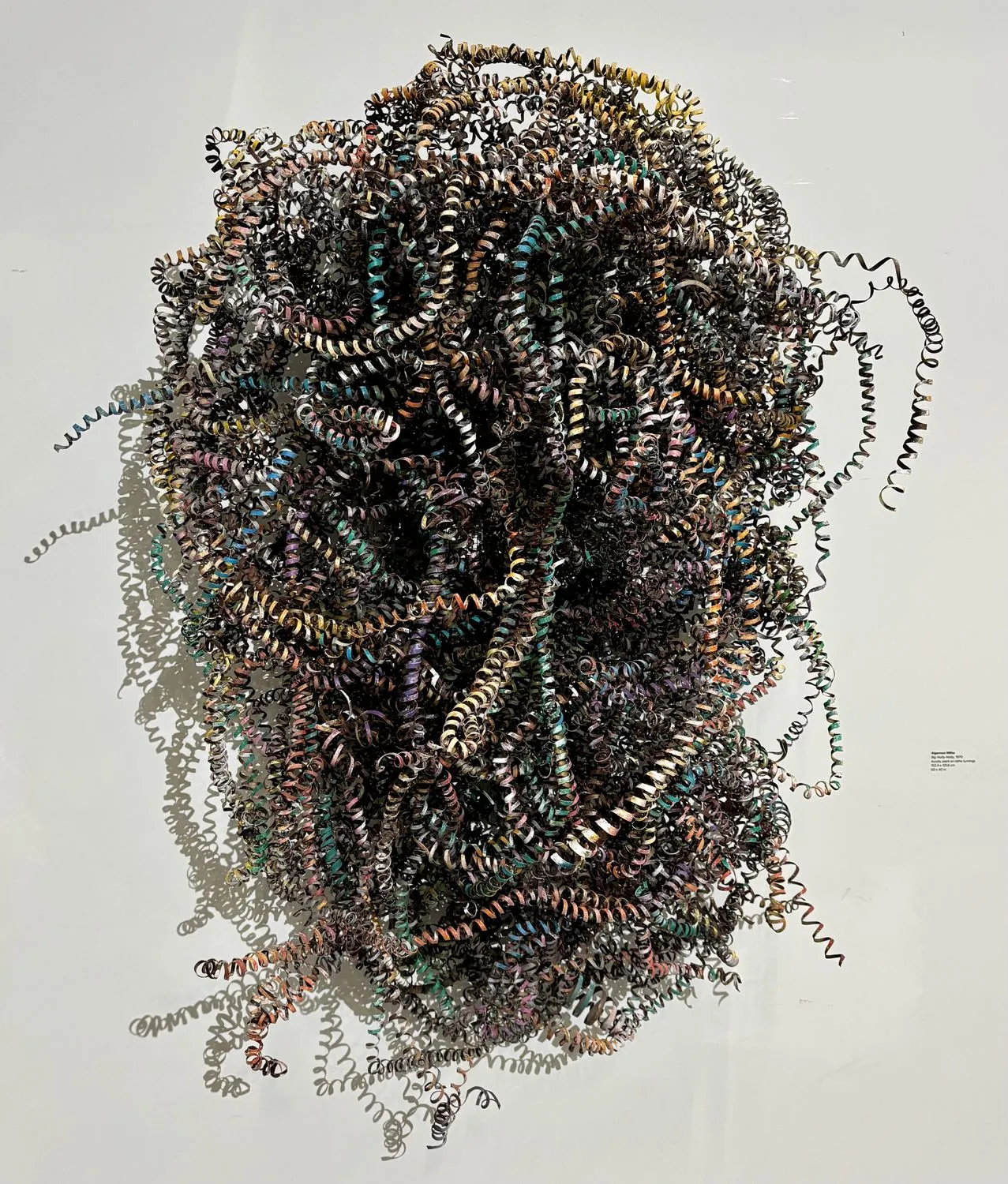

What is the Afrofuturist movement? Led by and for Black visionaries and creatives, the movement has no end date and has consistently used all mediums available, from traditional craft to the most urgent of emerging technologies, to envision and propel alternative futures into the world. These futures don't just include Black voices, they center them. These futures are consistently presented in technicolor, incorporate music and texture, and explore the complexity of joy and pain that’s been overcome.

We see in the cavernous space of Ethan Cohen's 17th street gallery not Miller's iconic plaza though, nor his Tree of Life public sculpture. Rather his first solo exhibition, Afrofuturism and Beyond, we see here as we often do in galleries the more salable works: capital P paintings. And while I hesitated at first to imagine how the energy of Miller's grand public projects could be held in the humble oil on canvas format, I was surprised at how immersed I became in the world Miller fabricates in two dimensions.

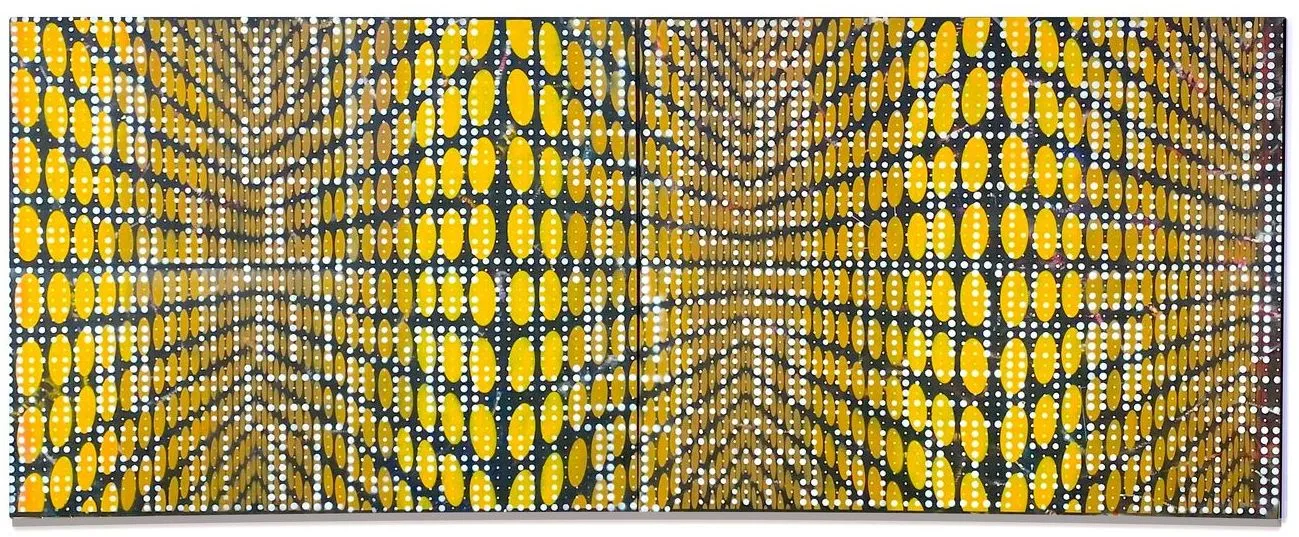

Imagine standing alone in the middle of Frederick Douglass Circle: it's a windy fall day, and buses trudge along on the perimeter. Tourists are trying to cross the streets at the wrong time, and cyclists ring their bells at cars in the bike lanes. But all this culminates in a big, whirlwind of energy moving around your body. You're at the center of his red and yellow sundial, perched above it all on a raised, geometric plinth shaded by the branches of a tree. Time is suspended, just as your body is between the park and the energy of Harlem to the north. This multisensory world is what Miller is so adept at conjuring, and the ability to bring us out of our daily trudge and into another, lighter dimension is what gives his entire oeuvre the tinge of the spiritual. Looking at Miller's canvas titled Sun Ra #3 at the very front of Ethan Cohen, puts you on the floor of a concert, the lights and sweat and brass clinking around you like silverware.

The music of Sun Ra, jazz, and lyric poets was a major inspiration to Miller and all the other artists included in this small survey of Afrofuturism. And music is what brings the canvases to life in their flat form. I thought of this as I wandered the lower floor, a truly massive space with old crumbling brick walls hidden behind the plywood slabs supporting each artwork: a woman on the upper floor was sweeping, and in the quiet of a rainy Thursday afternoon, the rhythmic sweep created a soundtrack for my looking, as surely rhythm guided Miller's brushes.

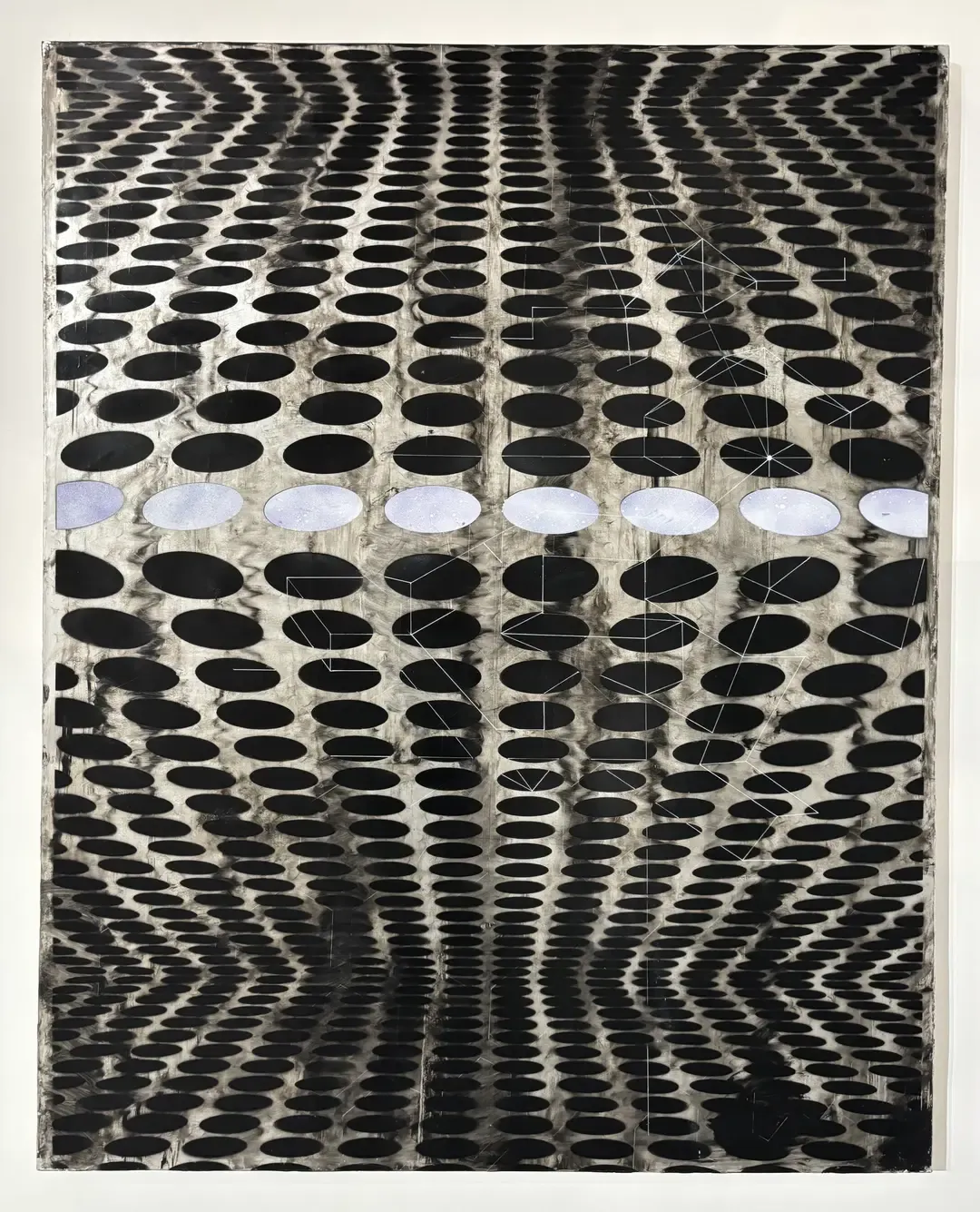

I fell into the deep inky black paints of Miller's canvases. In traditional oil paint theory, black is a color never used: we are instructed to mix dark colors like red, blue, and green to achieve shadows. Black creates a void that has been considered too harsh, too absolute. Miller and many other Black artists after him have therefore harnessed the use of black pigment as a statement: think of Storefront's groundbreaking installation by Amanda Williams. In a collection of Miller's more recent paintings, he plays with positive and negative space and scale with a nearly psychedelic array of stencils: black outlines of spheres lend perspective to each canvas, folding us in and over ourselves, whether the black pigment is the dark interior of a tunnel or the shadow defining the sphere of light. Miller describes this trip as "multidimensional being-ness in a new unified visual field." Abstract, quite colorful backgrounds ground each canvas, and the overlays give an ordered and even technological feel to each work. This high tech feel is heightened specifically in Post Pythagoras Break Down, my favorite of the show: Miller's paints were applied here not on canvas, but on reflective board.

But these works and their worlds seem to reference only a time long past. Today we seem desperate for change, for tangible action, and for the intense proximity that art and culture in 1960s New York stank of. We see it in the election of Zohran Mamdani in contrast to the consistently stale actions and statements taken by career democrats. But we also feel it in an art world that feels hollow and perhaps equally stale: lacking a unified movement, an energetic core, a critical stance.

Surely collectors will buy the canvases that so effortlessly blend reflectivity and void in Ethan Cohen. But emerging artists could take more cues perhaps from Miller's life and actions: coming together, listening to music, making new worlds and taking a stance. Miller and the Afrofuturists exhibited alongside him here never felt they had to be one thing, or curate one brand. They embrace technology as much as traditional handicraft, embraced African American culture and struggle while never forgetting African heritage. One medium does not define this continuing movement, nor could one medium ever. When our generation is asked what the future could look like, Miller shows just how powerful it can be to look to the past while fabricating the future.