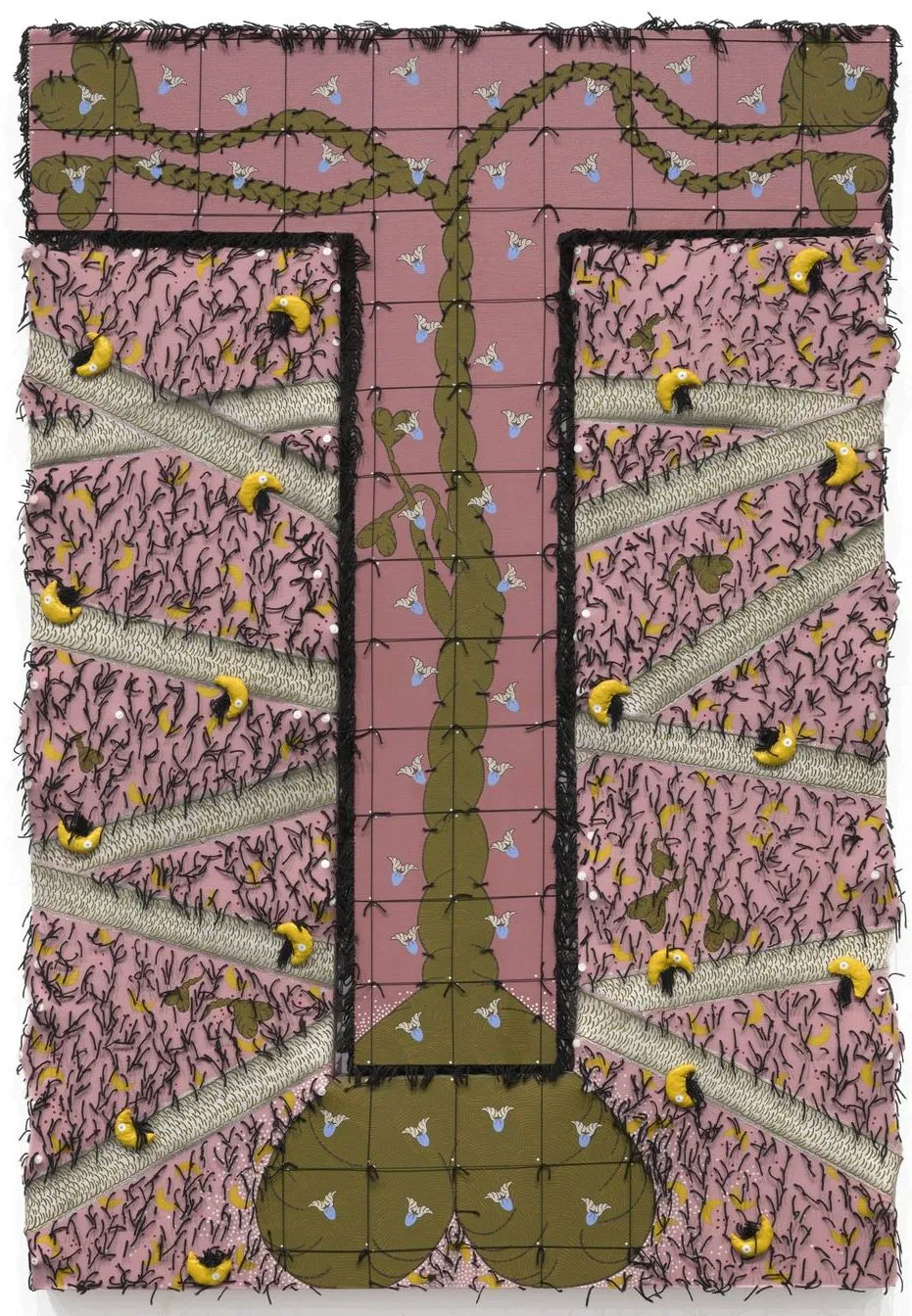

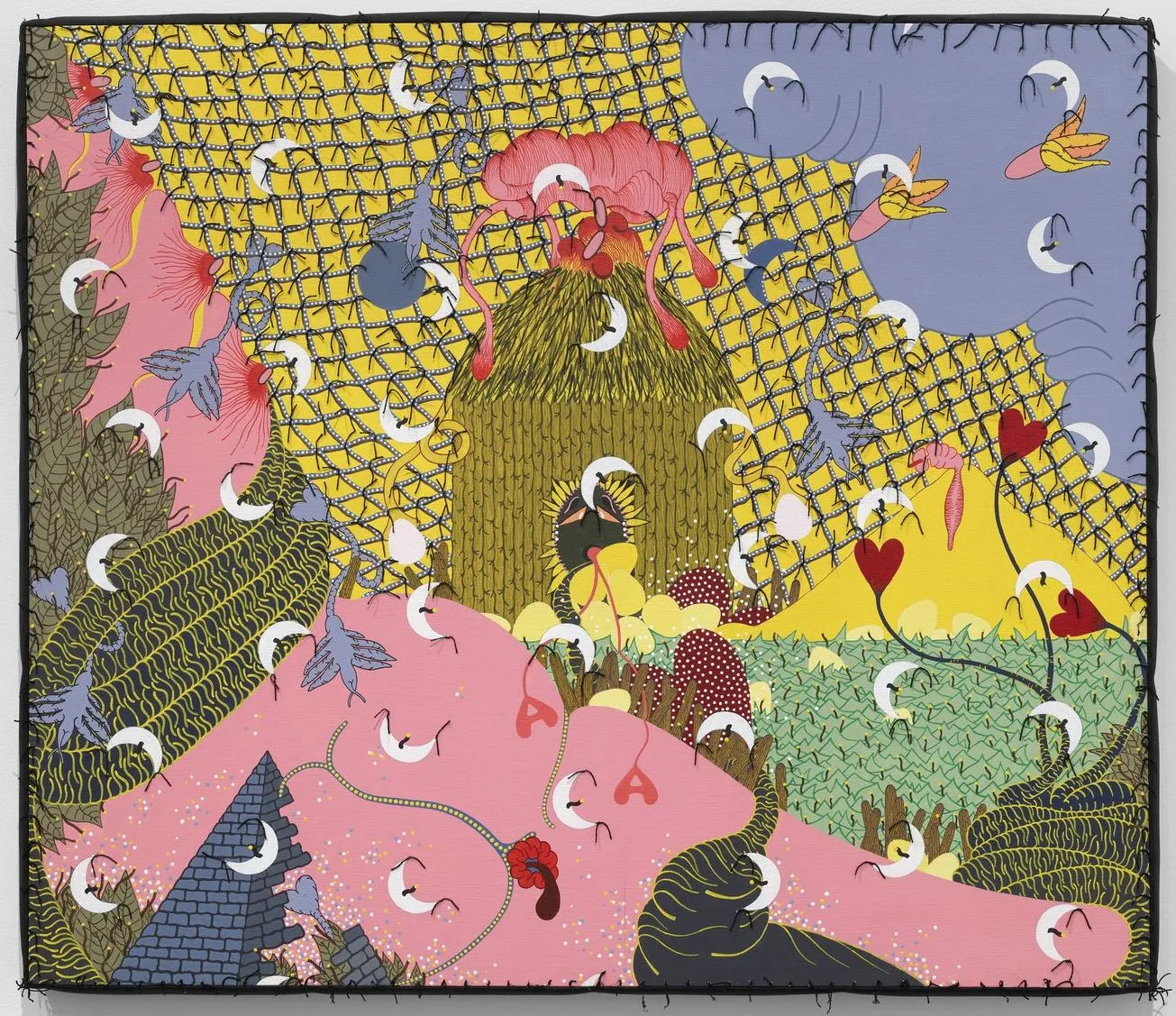

Franklin Williams, Baby Girl #2, 1970. Photo by Julia Featheringill; Courtesy of The Bell.

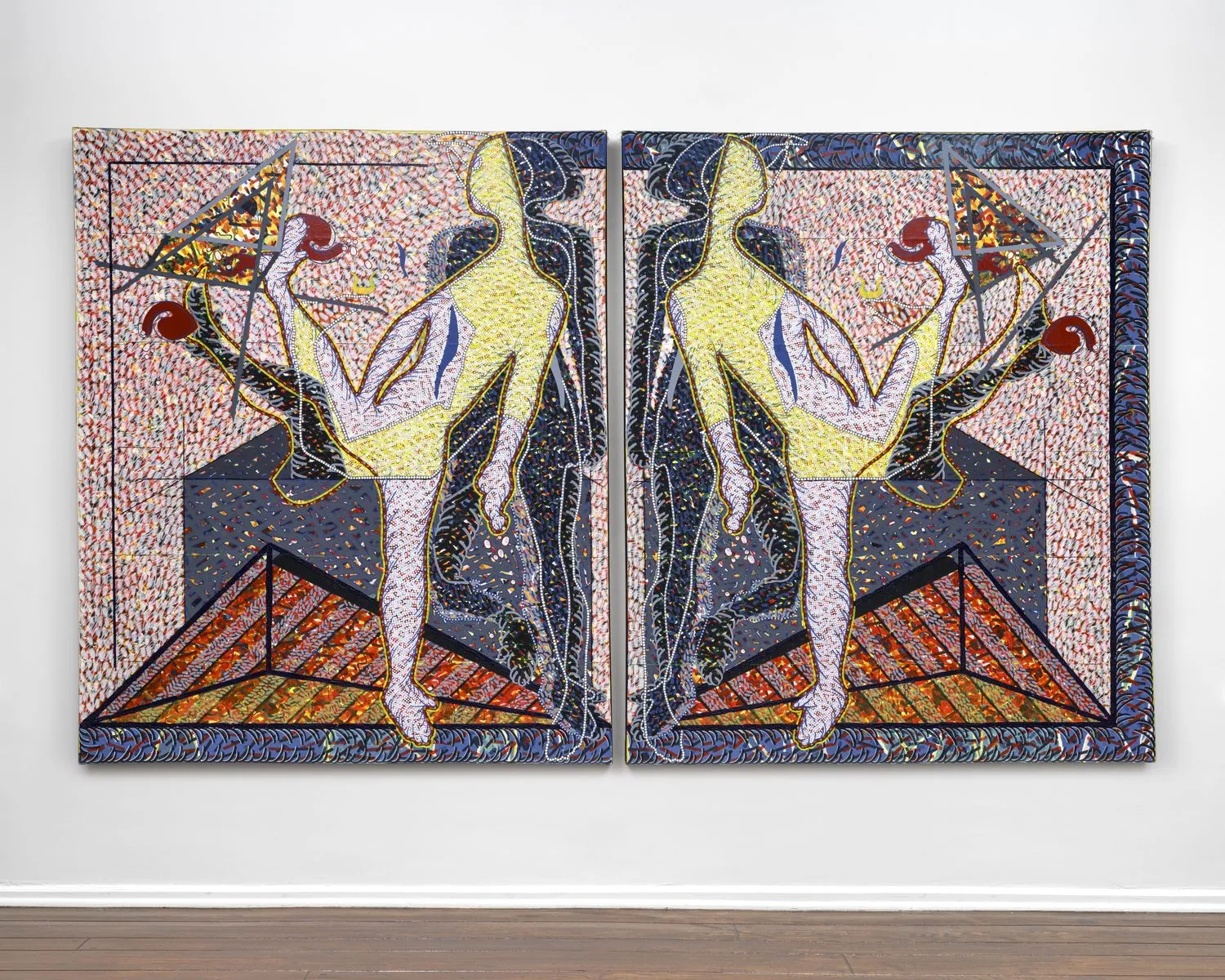

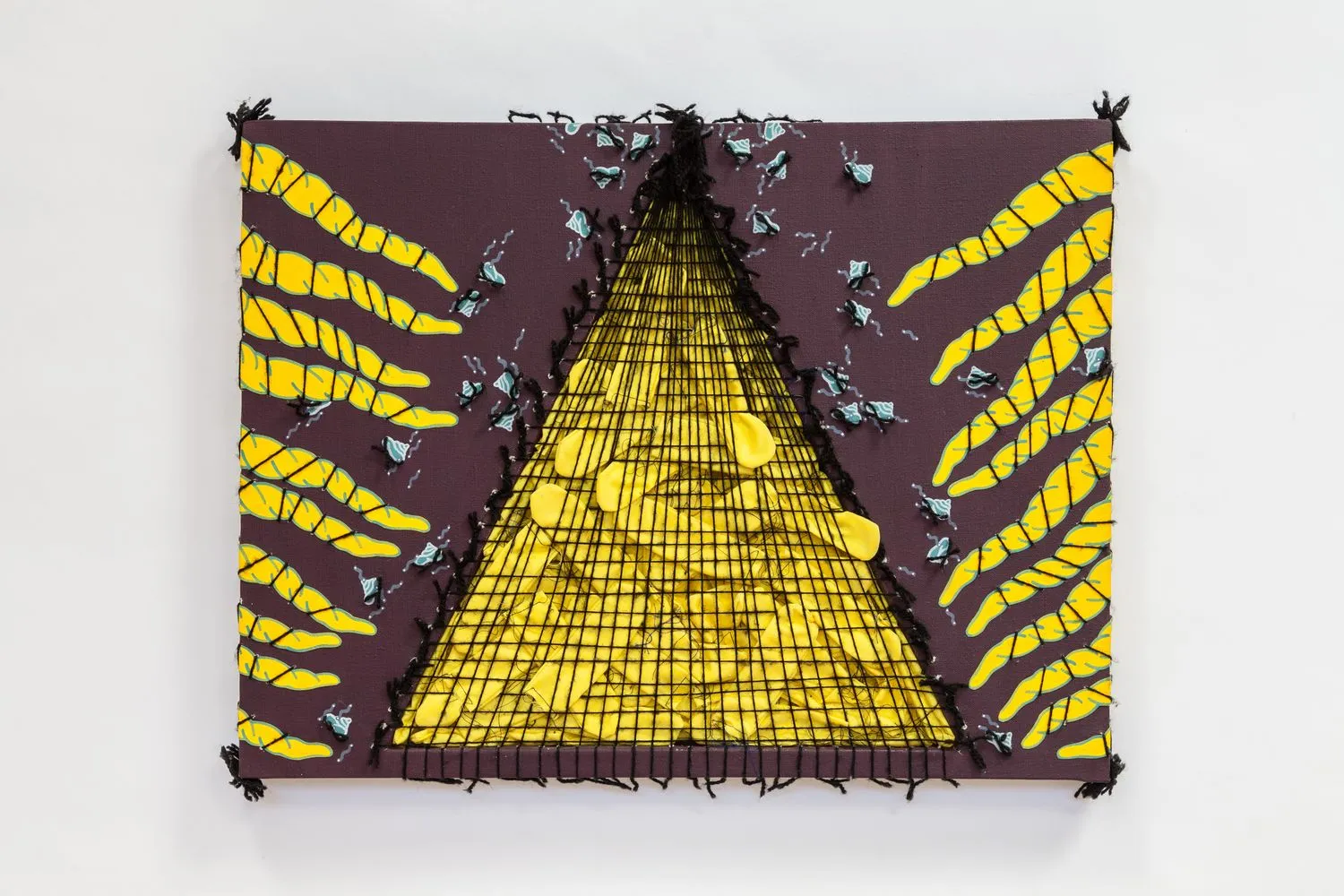

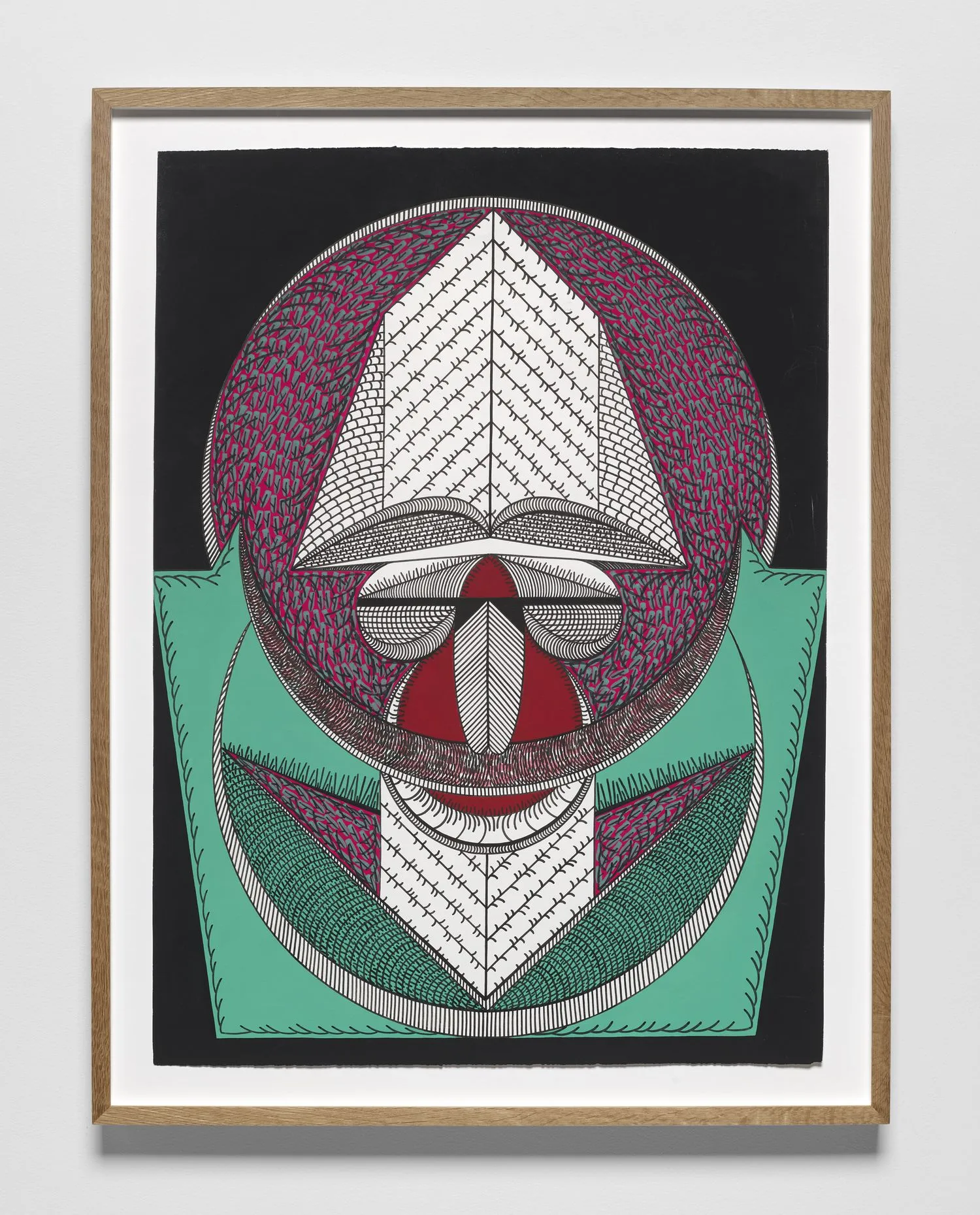

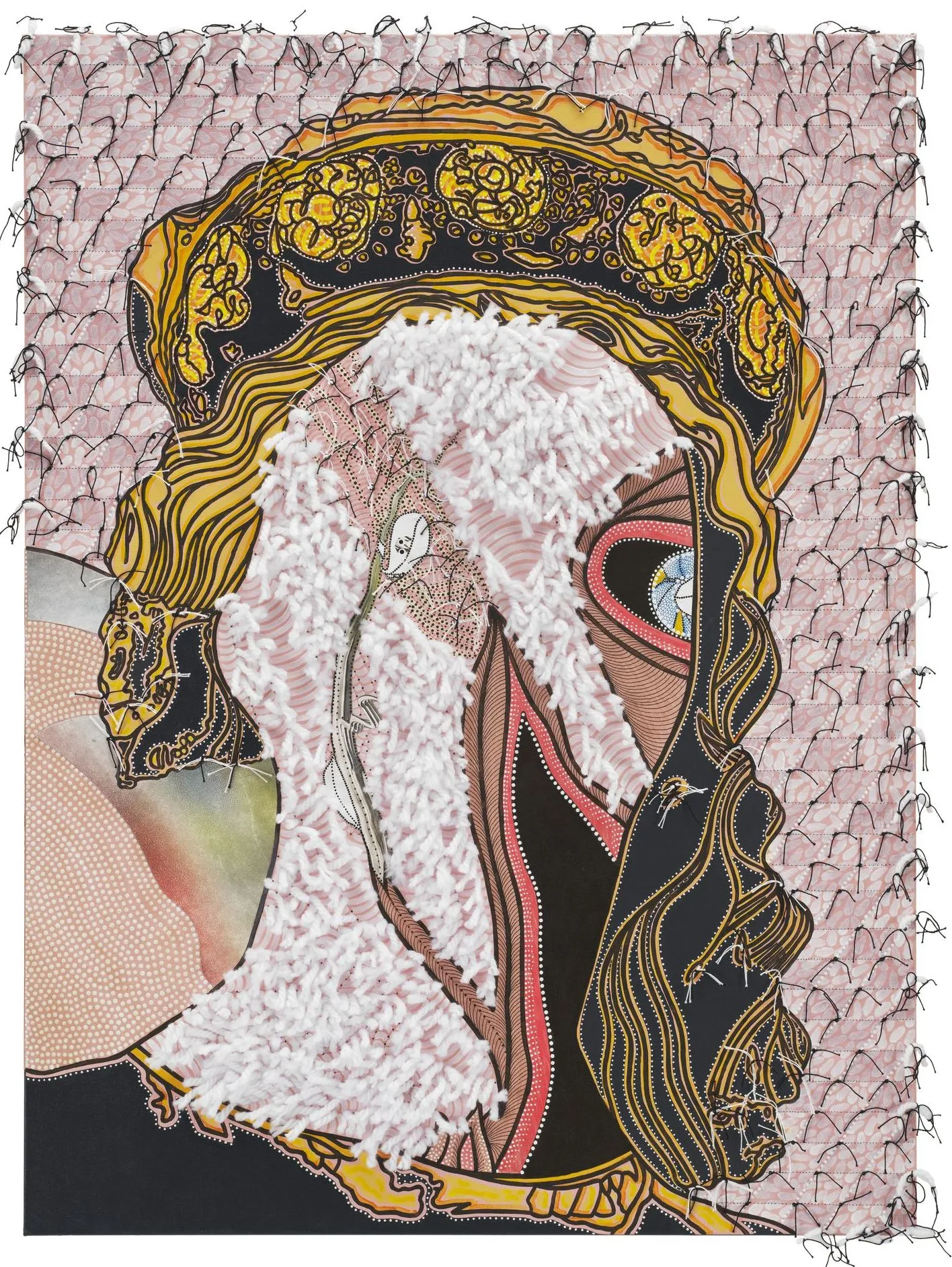

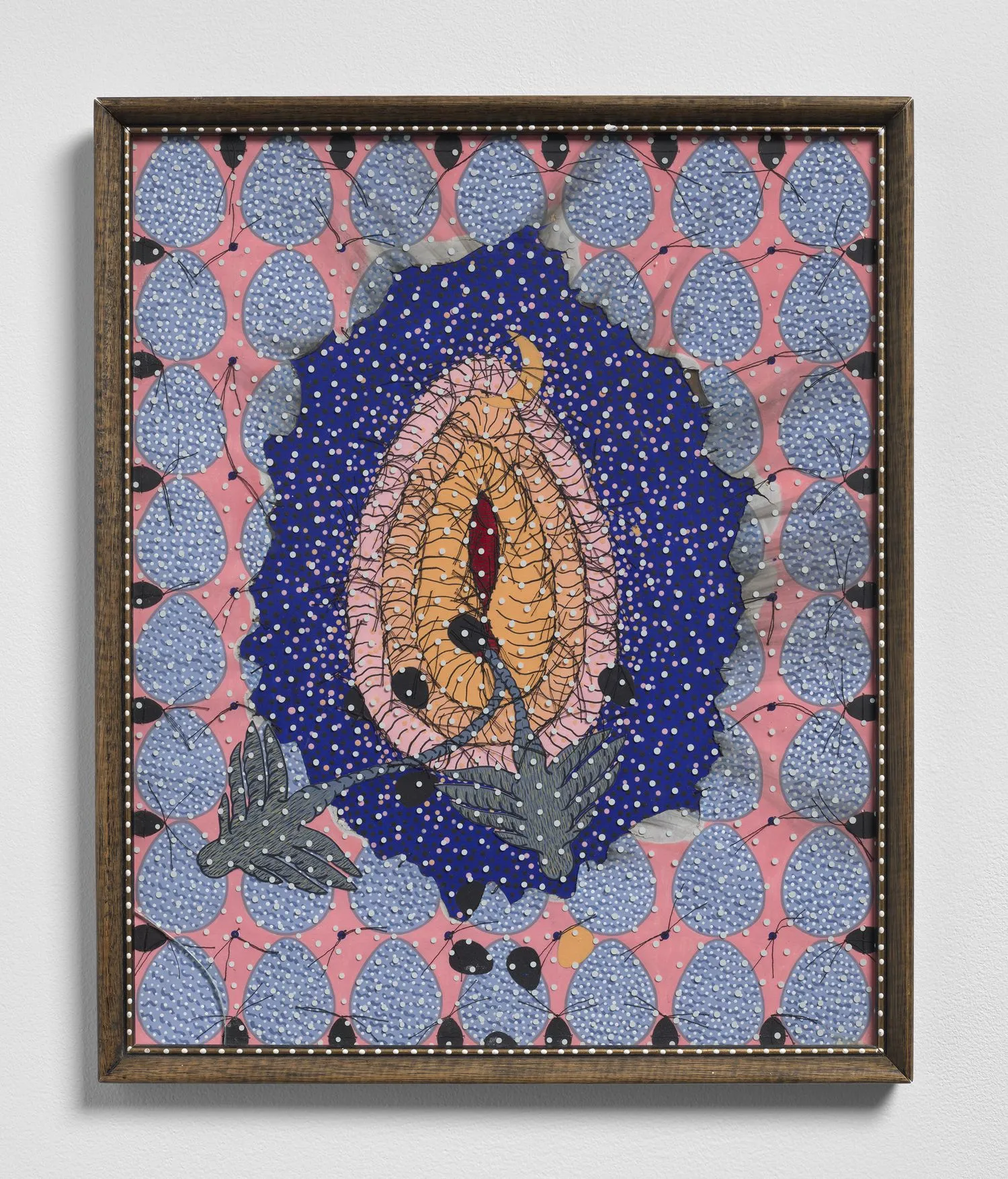

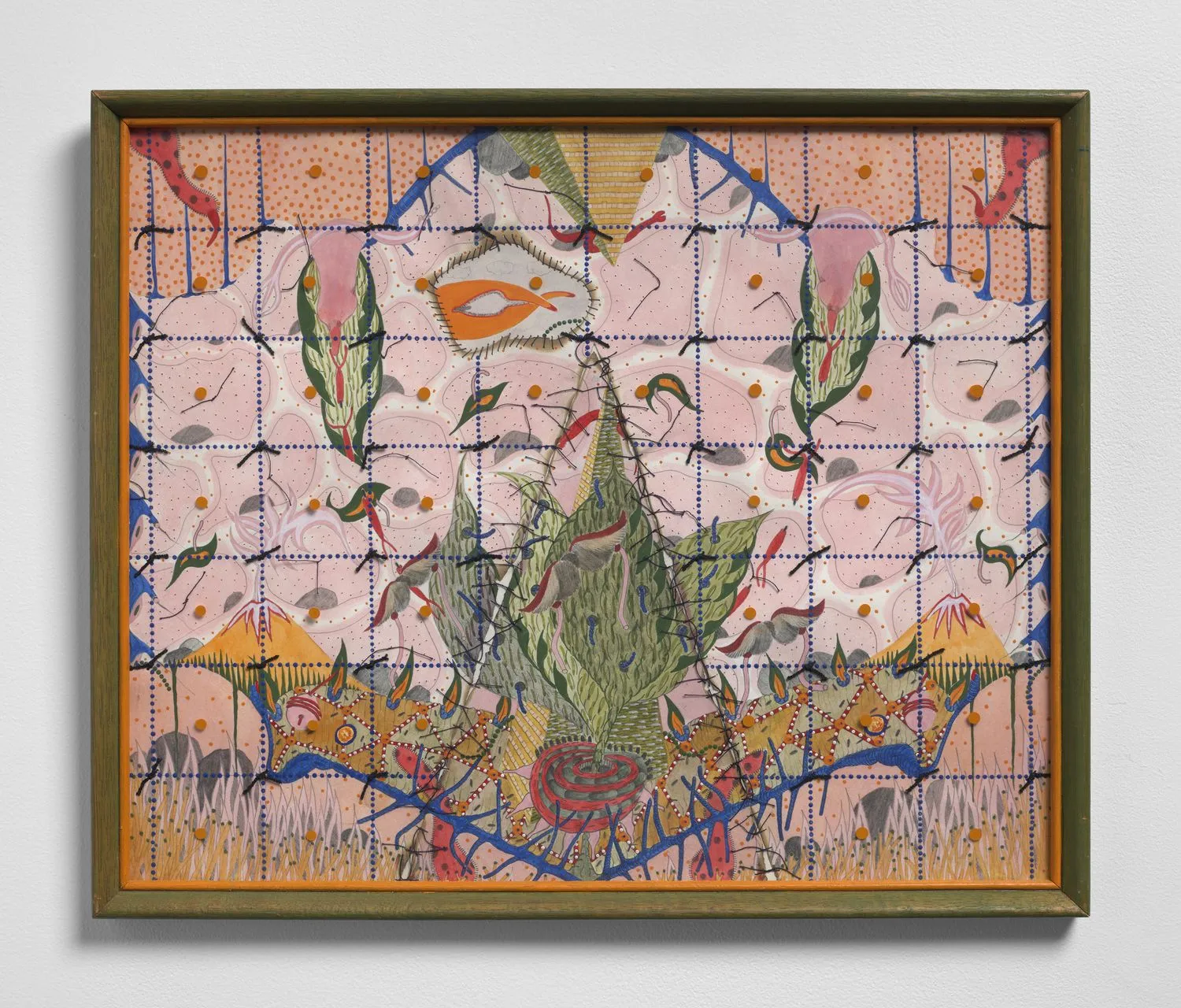

Franklin Williams, Baby Girl #2, 1970. Photo by Julia Featheringill; Courtesy of The Bell. Franklin Williams, an auto-didactic multimedia artist, is a norm-defying octogenarian whose oeuvre has been escaping definitions, eluding canonical conclusions, and meandering through the outer rims of canonical art history for more than six decades. Integrating painting and drawing with needlework, crochet, and other fiber-related techniques he learned from his family in rural Utah, Williams foregrounds textures, colors, and organic forms as hallmarks of an entirely unique artistic alphabet. These are the fibers of his extraordinary "personal cosmos," which is finally getting the institutional attention it deserves.

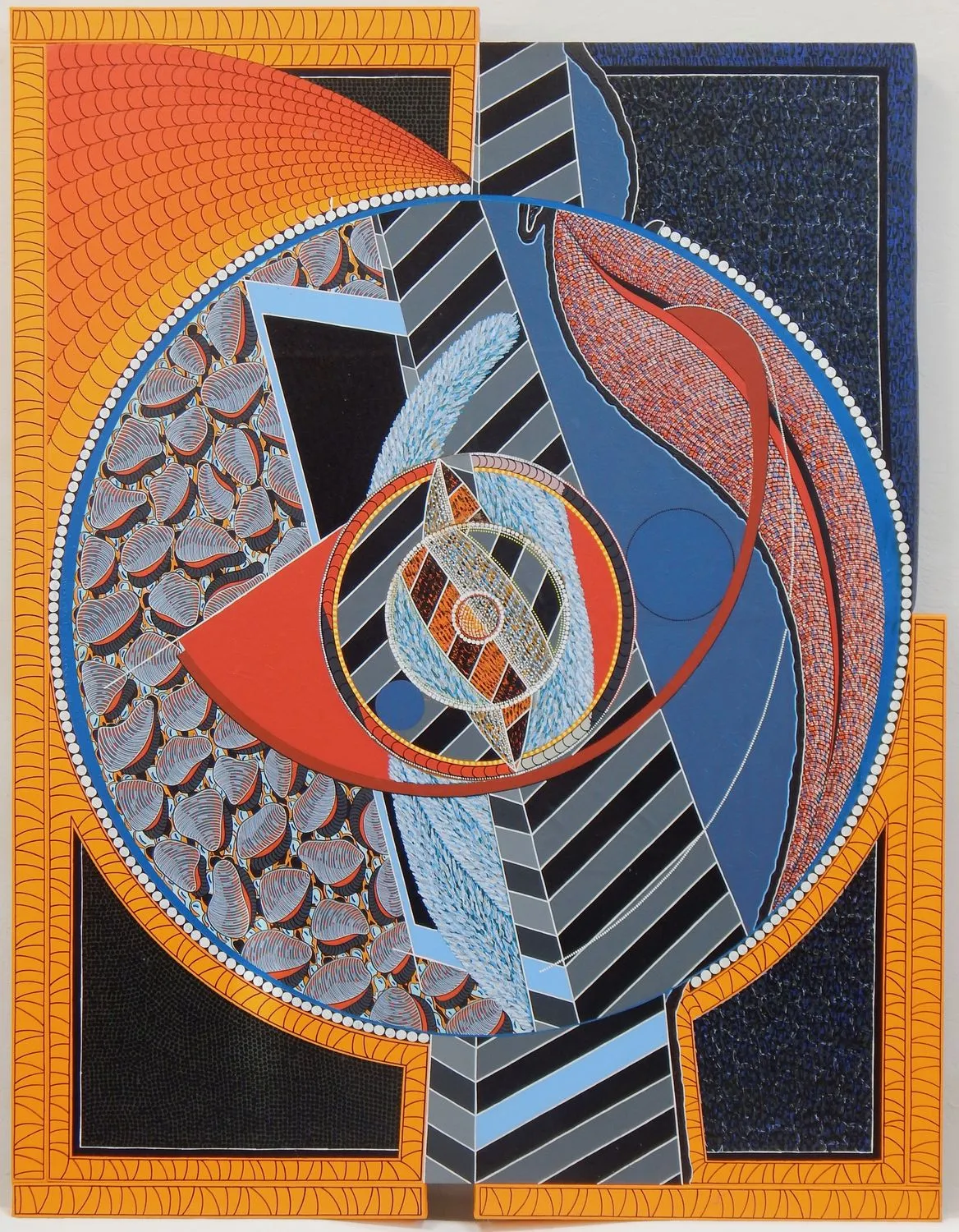

Representing a carefully curated selection of more than half of a century of relentless artistic activity, the show Franklin Williams: It's About Love at the David Winton Bell Gallery (The Bell) at Brown University is a well-deserved nod to a lifetime of dedication to emotion, texture, and artistic expression. Frequently regarded as a forerunner and contemporary of the Pattern and Decoration Movement of the 1970s, Franklin Williams developed a distinct practice that upholds a tension between figurative and abstract art, austerity and humor. However, his practice remains deeply embedded in exploring universal human themes, such as familial and romantic love, death, and sorrow.

Despite eluding affixation regarding specific movements, Williams was included in the 1972 Nut Art exhibition at California State University Hayward and the 1967 Funk exhibition curated by Peter Selz at the Berkeley Art Museum. His work was also recently a part of the exhibition With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985, curated by Anna Katz at LA MOCA in 2019, regardless of not being part of any of the historic P&D exhibitions.

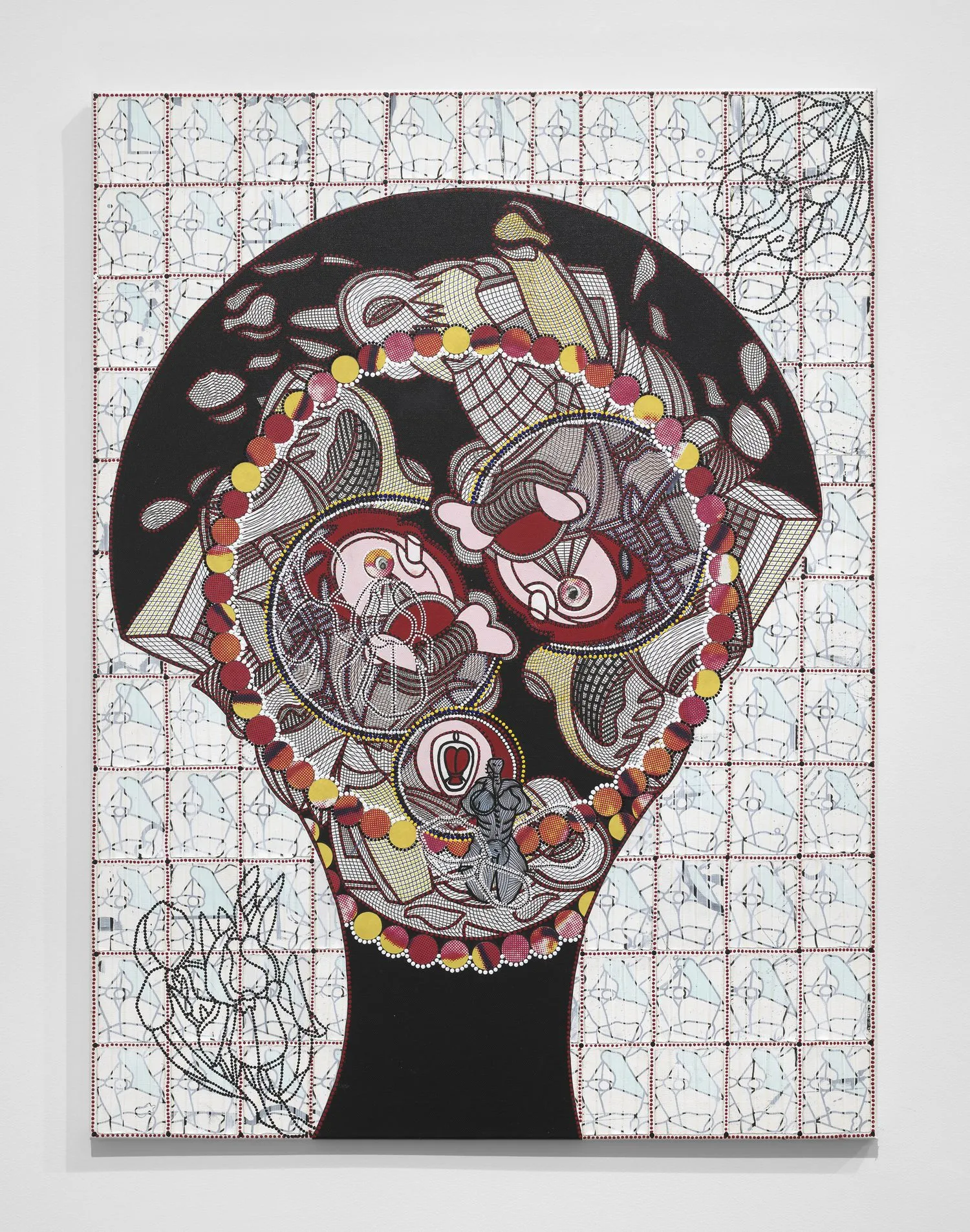

Featuring forty artworks, spanning from sculptures to intricate canvases and works on paper, the exhibition is curated by Director of Exhibitions of the Brown Arts Institute (BAI) and Chief Curator of the Bell Gallery at Brown University, Kate Kraczon. "A deeply symbiotic relationship," as Kraczon described it, the show relies upon curatorial trust. Intensely collaborative, the exhibition developed in close alignment with the artist, who pointed out major works and periods in their conversations, helping chart the curatorial narrative.

The show Franklin Williams: It's About Love centers on six decades of the artist’s daily meditative studio practice. Since the 1970s, Williams has been based in Petaluma, California. His studio serves as an extension of his home—a hub of ancestral heirlooms and Williams' artwork intermixed with his family’s handmade quilts, furniture, and other art objects. Art and poetry permeated his upbringing, greatly determining his diaristic approach to art-making. "Much of the work in the exhibition is directly autobiographical," the curator notes.

"Objects from the early 1980s, such as Last Gate and Cutting Apron Strings, were created as Franklin processed the death of his parents," Kraczon explains. "The visual influence of international travel with his family is often referenced in the titles of works like Secret Sweet Slovakia, and he has explicitly described Pink Tea (1972) as a kind of family portrait: the fleshy pink hairy and bulbous surface of the painting, the glandular imagery of testes and ovaries, and the fluttering eggs and crescent moons that signal fertility."

Kraczon also recognizes a certain Bay Area Funk element to Williams' work, ranging from the colors, transdisciplinary textures of fiber and wood alongside canvas and paper, and the slightly grotesque but humorous sexual imagery that becomes particularly evident in works such as the Pink Tea.

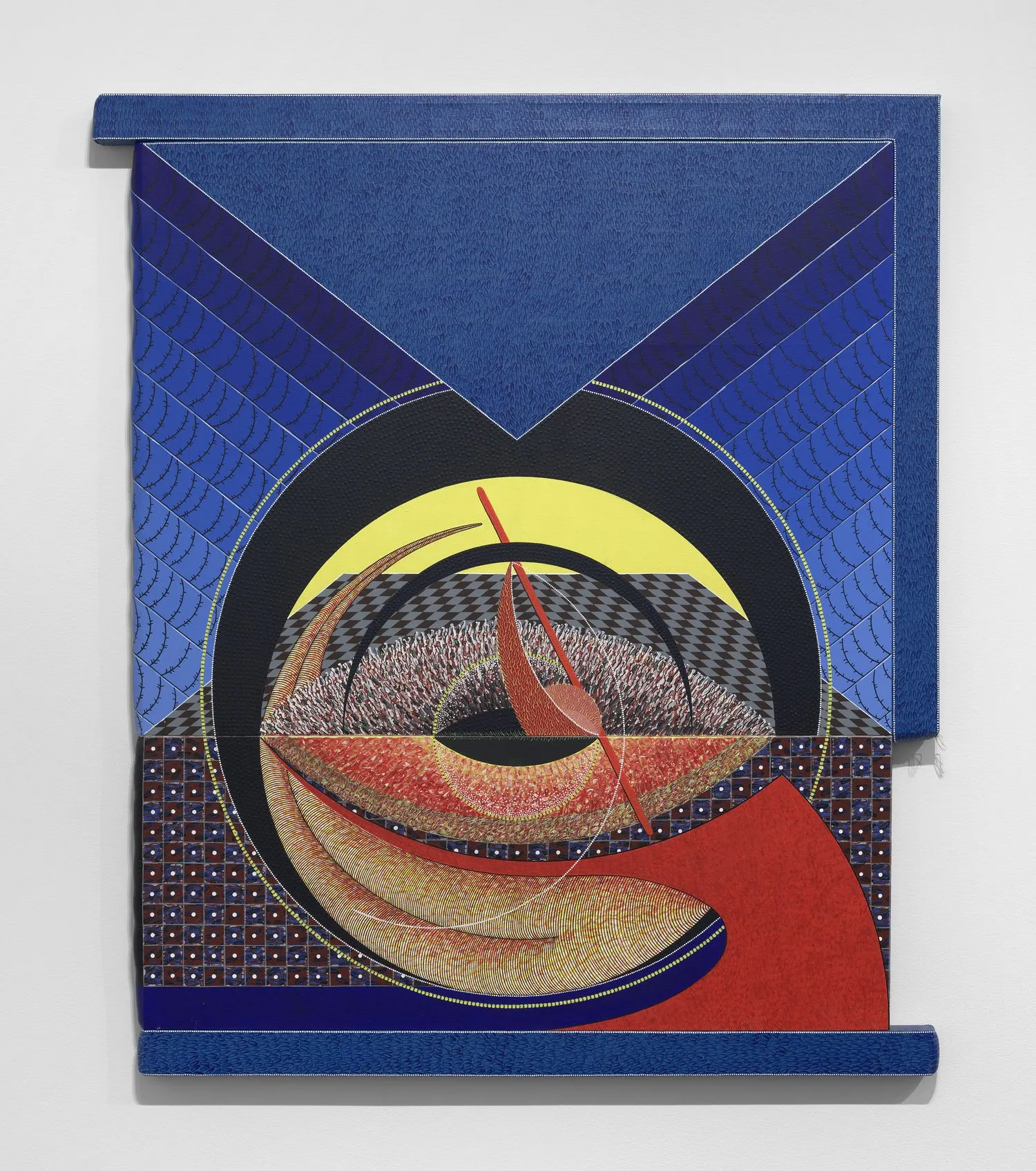

On view at The Bell at Brown University in Providence until December 8th, 2024, the exhibition Franklin Williams: It's About Love unravels the threads of human emotion. It is a roadmap of a lifetime—an intricate path filled with joy, sorrow, lust, and love. It is a tale of broken hearts, mended wounds, euphoria, and hardships. But most of all, it is a story about hard work and meticulous labor embedded within the objects, revealing "the temporality of its making," as underlined by Kate Kraczon.

Even those of us who do not have experience as makers can detect the labor and time needed to produce these thousands of marks, whether dots or other patterns, knotted fiber, or slight shifts in colors that cover the surfaces of his objects. The traces of this labor are affective: there is an emotional response to recognizing the careful repetition of the artist's hand.