Chess of the Wind (1976) by Mohammad Reza Aslani

Chess of the Wind (1976) by Mohammad Reza Aslani The Iranian New Wave stands as one of the most poetic and profound movements in global cinema, reshaping storytelling through its innovative approach to narrative, aesthetics, and social commentary. Emerging in the 1960s as a distinct alternative to the commercial mainstream cinema that preceded it, this cinematic renaissance challenged conventions and offered a window into the complexities of Iranian society. It blended realism with allegory, introspection with bold critique, and combined poetic visuals with deeply humanistic storytelling, redefining the language of film. Unlike mainstream cinema, the filmmakers embraced minimalism, allowing silence, symbolism, and subtle gestures to carry profound meaning. Often working within the constraints of censorship and limited resources, they crafted films of remarkable depth and beauty, exploring subjects often neglected or suppressed.

The movement was more than a stylistic shift; it was a cultural awakening. Emerging during the cosmopolitan and yet turbulent period of the 1960s-1970s, the movement responded to the tensions of a rapidly modernizing society grappling with its historical, political, and spiritual identity. In this charged atmosphere, filmmakers turned to cinema as a means of resistance and cultural reclamation, blending allegory with realism to critique the injustices of their time and explore the complexities of Iranian identity.

Rooted in the lives of ordinary people, these films transcend their specific contexts to explore universal truths. They employ visual metaphors and non-linear narratives to comment on issues such as social inequality, existential despair, and the search for freedom. As much about what is left unsaid as what is spoken, these films offer profound insight and moments of haunting beauty. This artistic approach created a unique cinematic language that resonated far beyond Iran's borders, earning the movement a place in the annals of world cinema.

This February, London's Barbican Cinema will pay homage to this transformative era with Masterpieces of the Iranian New Wave. Running from February 4th to 25th, 2025, the program showcases nine meticulously restored films that exemplify the spirit and ingenuity of Cinema-ye Motafavet. Curated by Ehsan Khoshbakht, this landmark season offers audiences a rare opportunity to experience the movement's breadth, from Ebrahim Golestan's Brick and Mirror to Forough Farrokhzad's The House Is Black. Each screening will illuminate the collaborative, subversive, and visionary energy that defined the New Wave, set against the backdrop of a nation on the cusp of profound change.

Khoshbakht emphasizes the collective spirit among New Wave filmmakers, a rare quality in Middle Eastern cinema.

Almost always subversive, these films reveal the contradictions of Iranian life with haunting clarity. They not only capture the genesis of an Iranian cinematic revolution but also foreshadow the social and political upheavals that culminated in the 1979 revolution. Tragically, this same revolution would lead to the banning of many of these trailblazing films.

This selection includes some of the movement's defining works. From the hauntingly lyrical Chess of the Wind to The Sealed Soil, the earliest surviving Iranian feature directed by a woman, these films challenge audiences and offer fresh perspectives on a changing world.

Abbas Kiarostami's Experience (Tajrobeh), his debut feature co-written with Amir Naderi, delicately unveils the emotional landscape of a young man navigating the complex shift from rural life to the bustling metropolis of Tehran. The film immerses us in the protagonist's sense of isolation, capturing the internal turbulence of a youth faced with a foreign urban environment. Kiarostami's film, a blend of documentary realism and poetic imagery, invites us to feel the weight of his protagonist's experience—an everyman struggling to find his place in a world that feels overwhelmingly large. Experience taps into universal themes of identity and belonging, offering a glimpse into the transformative power of memory and self-discovery.

The film's autobiographical elements, enriched by Naderi's influence, are a haunting reflection of Kiarostami's own journey. Together, the pair, working within the confines of the early Iranian New Wave, crafted a narrative that ebbs between reality and the dreamlike. Experience sets the stage for Kiarostami's future works, foreshadowing his ability to fuse the personal with the universal, creating a film that feels as intimate as it does monumental.

Amir Naderi's Waiting (Entezar) is an experimental masterpiece, a haunting meditation on time and solitude that shatters traditional narrative conventions. In this nearly wordless film, a young man waits for a bus in a desolate landscape, his every moment suspended in anticipation. The film’s minimalist approach—its sparse dialogue and dreamlike visuals—allows Naderi to explore the protagonist's internal world, where anxieties and unspoken desires come to the fore.

Shot just a year after Experience, Waiting marks a departure from realism, merging the illusory with the documentary. The film's eerie silence, punctuated only by the sounds of nature and distant echoes, amplifies the protagonist’s emotional isolation. Waiting lingers long after the credits roll, a meditation on the quiet tension between expectation and existential uncertainty. It is a precursor to Naderi's exploration of human endurance, a quiet yet powerful statement on the limits of the human spirit.

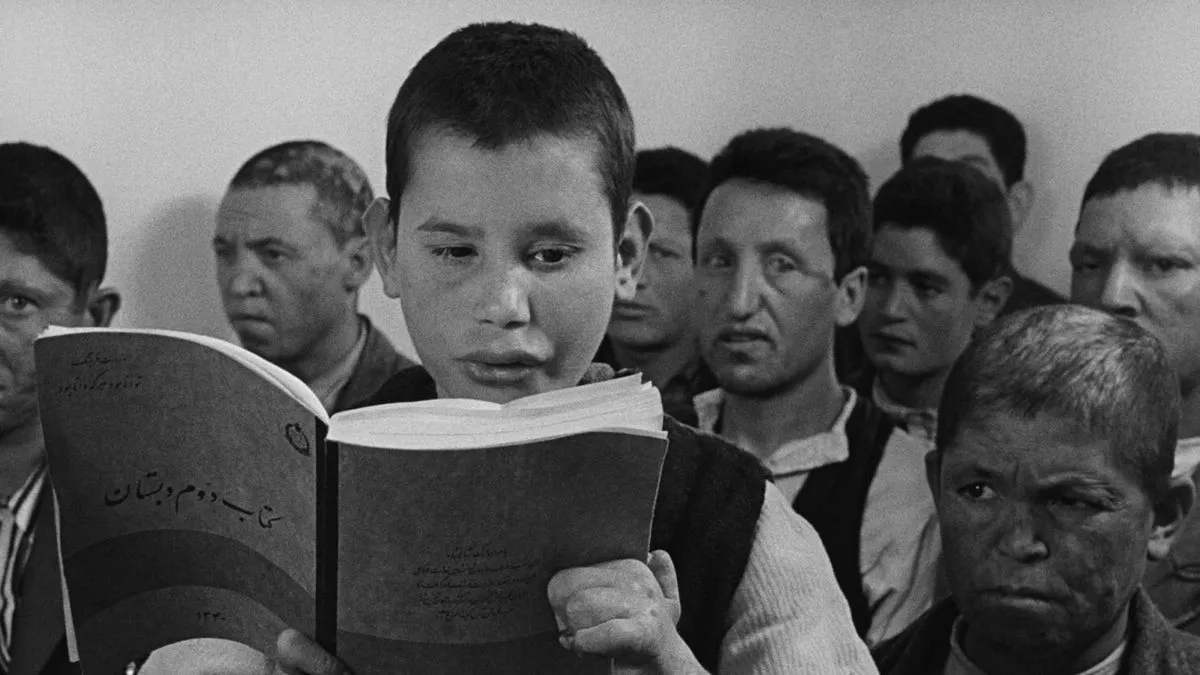

Forough Farrokhzad's The House Is Black (Khaneh Siah Ast) is a landmark film that defies traditional documentary filmmaking. In this 22-minute short, Farrokhzad brings us into the harrowing world of a leper colony, a place often hidden from the public eye. Her voiceover, tender yet unflinching, creates a bridge between the visual and the visceral, turning what could be a stark social commentary into a profound poetic meditation on suffering and resilience.

Farrokhzad's close-ups of the patients are not just images; they are windows into the depths of human dignity. The film's emotional power lies in its ability to transcend the pain it shows, transforming it into a universal reflection on life, death, and the fragile nature of existence. The House Is Black remains a touchstone in Iranian cinema, a film that challenges societal taboos and invites us to confront discomfort with empathy and understanding.

Marva Nabili's The Sealed Soil (Khak-e Sar Bé Mohr) is a rare cinematic gem, the earliest surviving full-length feature by an Iranian woman director. Set against the backdrop of pre-revolutionary Iran, the film explores the personal and societal struggles of a young woman trapped by the limitations placed upon her by both family and state. Through minimal dialogue and restrained yet powerful imagery, Nabili crafts a narrative that feels both intimate and revolutionary.

The protagonist's emotional turmoil, portrayed with quiet intensity, highlights the tension between personal desires and societal expectations. The film's themes of patriarchy and rebellion resonate deeply, making The Sealed Soil not only a feminist film but a poignant critique of a society on the brink of transformation. Its rediscovery offers a rare glimpse into a voice that had been stifled, and its legacy continues to inspire those who seek to challenge oppressive structures with subtle, yet powerful, storytelling.

Ebrahim Golestan's Brick and Mirror (Khesht o ayeneh) stands as a pioneering force in Iranian cinema, tackling themes of responsibility, fear, and alienation in the wake of the 1953 coup, which was orchestrated by the CIA and MI6. Often hailed as Iran's first true modern masterpiece, it centers on a taxi driver who discovers an abandoned child in his cab. His internal battle—whether to take responsibility or avoid the consequences—unfolds slowly, mirroring the protagonist’s profound moral dilemma. Golestan's cinematic style is bold, relying on striking visual experimentation to amplify this tension.

The film's stark black-and-white imagery complements its existential themes, with a narrative structure that remains unconventional even by today's standards. Brick and Mirror is one of the first Iranian modernist films, pushing the boundaries of cinematic form. Its portrayal of personal and societal responsibility in an uncertain world resonates powerfully, offering a timeless reflection on the human condition.

Bahram Beyzaie's The Stranger and the Fog (Gharibeh va meh) is a visually rich and symbolically layered film that blends elements of Persian theatre with the nuances of cinematic storytelling. Set in a fog-bound village, the film tells the story of a stranger whose arrival disrupts the lives of the locals, weaving a narrative that explores fear, power, and the unknown. Beyzaie's non-linear storytelling and heavy reliance on allegory create a dreamlike atmosphere, offering layers of meaning that invite multiple interpretations.

The film's mise-en-scène—characterized by fog and muted colors—enhances its ethereal, otherworldly quality. Beyzaie's exploration of societal divisions and human frailty strikes a potent critique of the social and political tensions of the time. The Stranger and the Fog lingers as a meditation on the tension between the individual and the collective, leaving a lasting impact on Iranian cinema's ongoing engagement with political and social themes.

Sohrab Shahid Saless' Far From Home (Dar ghorbat) is a hauntingly quiet exploration of immigration and isolation, following an Iranian man living in Vienna. The protagonist, an immigrant worker, drifts through the monotony of his daily routine, weighed down by the emotional toll of being far from home. Saless' minimalist approach—long, meditative shots and sparse dialogue—immerses the viewer in the protagonist's lonely existence, allowing the emotional weight to slowly build.

The film’s quietude speaks volumes, capturing the profound psychological impact of displacement and alienation. Far From Home is a poignant reflection on existential loneliness, identity, and the emotional burden of immigration. As a piece of Iranian New Wave cinema, it stands as a powerful meditation on the immigrant experience, poignant in its stillness and profound in its exploration of identity.

In The Crown Jewels of Iran (Ganjineha-ye gohar), Ebrahim Golestan crafts a daring short documentary that critiques the excesses of Iran's monarchy just before the 1979 revolution. Focusing on the opulent collection of royal jewels, the film casts them as symbols of wealth, power, and decadence at a time when the nation teetered on the brink of radical change. Golestan's approach is both poetic and subversive, using the jewels as a powerful metaphor for the inequality and corruption that festered within the ruling class.

The sharp visual contrasts and biting commentary make this documentary an indictment of the monarchy's extravagance. The Crown Jewels of Iran offers a rare glimpse into the opulence that would eventually contribute to the regime's downfall. Subversive and once banned, it remains a captivating exploration of the cultural and political tensions that defined pre-revolutionary Iran.

Mohammad Reza Aslani's Chess of the Wind (Shatranj-e baad) is a visually stunning and politically charged film that delves into the moral decay and intrigue of Ira's aristocracy. Set in an opulent mansion, the narrative follows a family caught in a web of betrayal, manipulation, and power struggles. Aslani's intricate plot and the lush cinematography—emphasizing light and shadow—create an atmosphere of tension and mystery, reflecting the political unrest of the time.

Chess of the Wind is an allegorical commentary on the decline of the old order in Iran, making it a poignant critique of the societal structures that the revolution would soon dismantle. Banned following the 1979 revolution, it remained unseen for decades, but its restoration has allowed it to be rediscovered as a masterpiece of Iranian cinema. Both The Crown Jewels of Iran and Chess of the Wind are now celebrated as suppressed cinematic treasures that not only showcase the artistry of Iranian filmmakers but also reveal the roots of decadence that helped precipitate the revolution.