Khashayar Javanmardi, Caspian. Courtesy of Loose Joints

Khashayar Javanmardi, Caspian. Courtesy of Loose Joints The Caspian Sea, the largest enclosed inland body of water on Earth, has long been a symbol of natural abundance and beauty. Its shores span five countries—Iran, Russia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan—each with deep cultural and economic ties to the sea. For centuries, the Caspian was a vital resource, providing fish, caviar, and a trade route between East and West. Yet, in recent decades, this once-thriving ecosystem has suffered immense environmental degradation. Pollution, overfishing, and the looming threat of climate change have drastically altered its delicate balance, putting both the sea and its surrounding communities at risk.

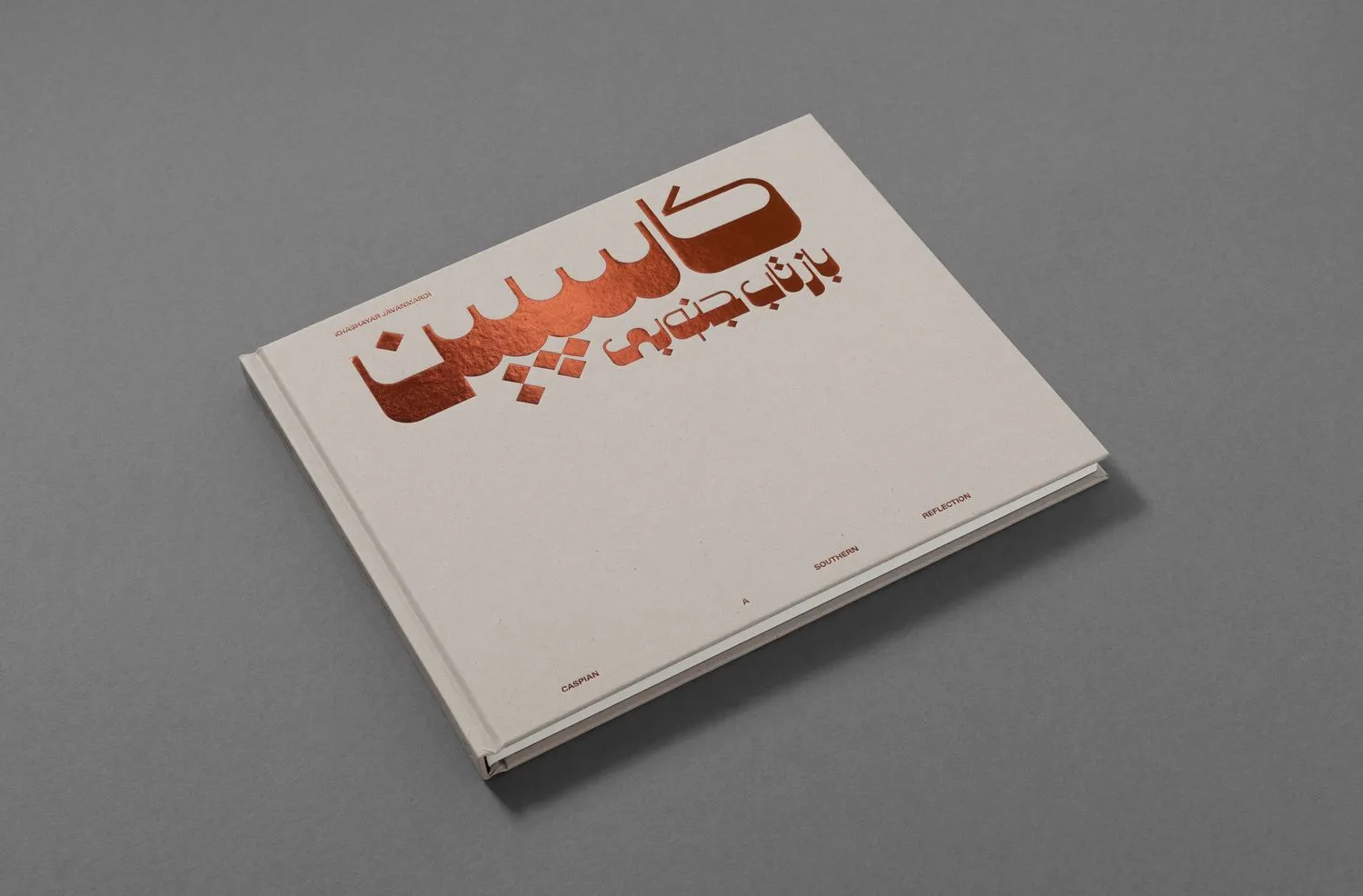

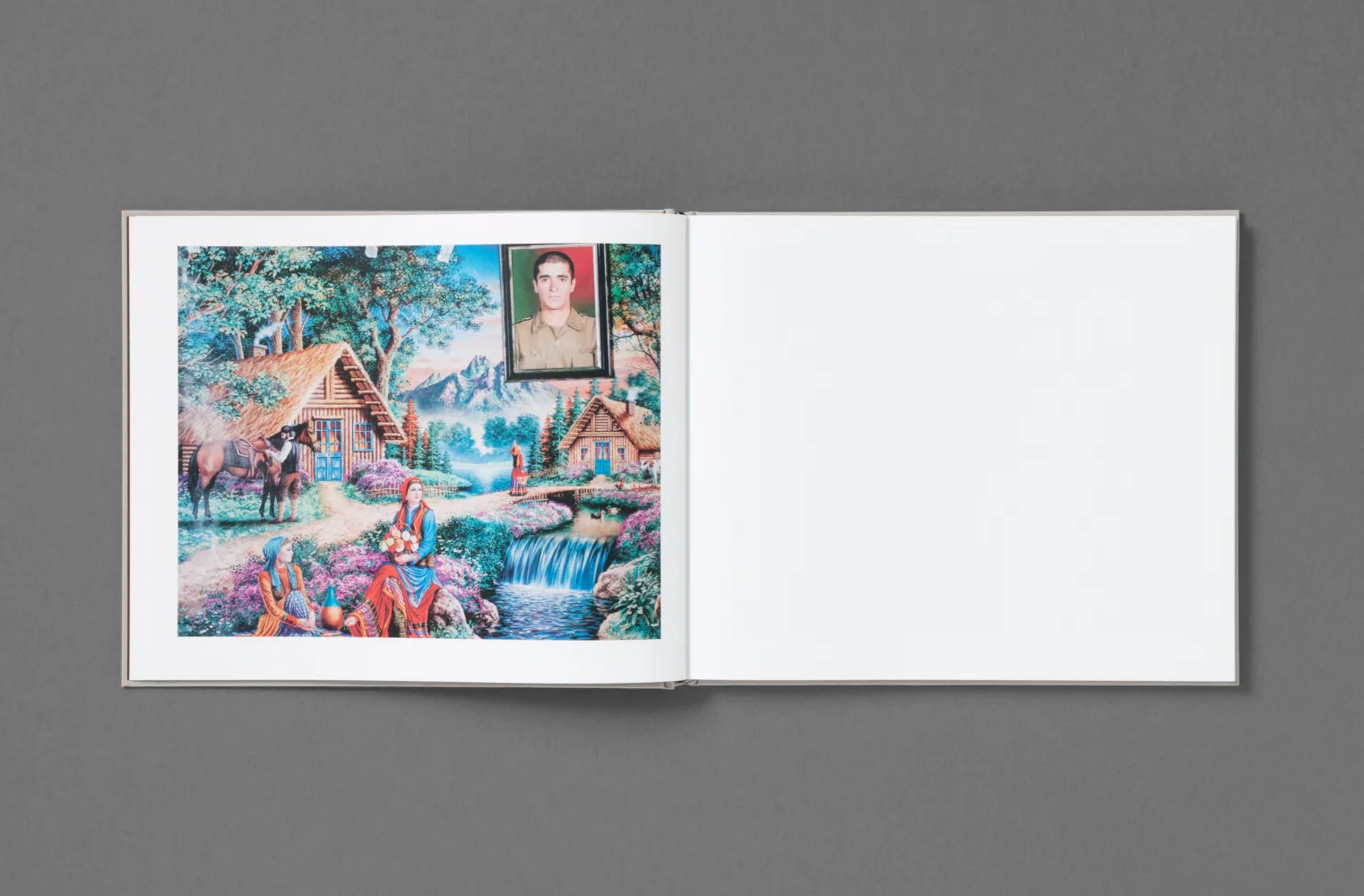

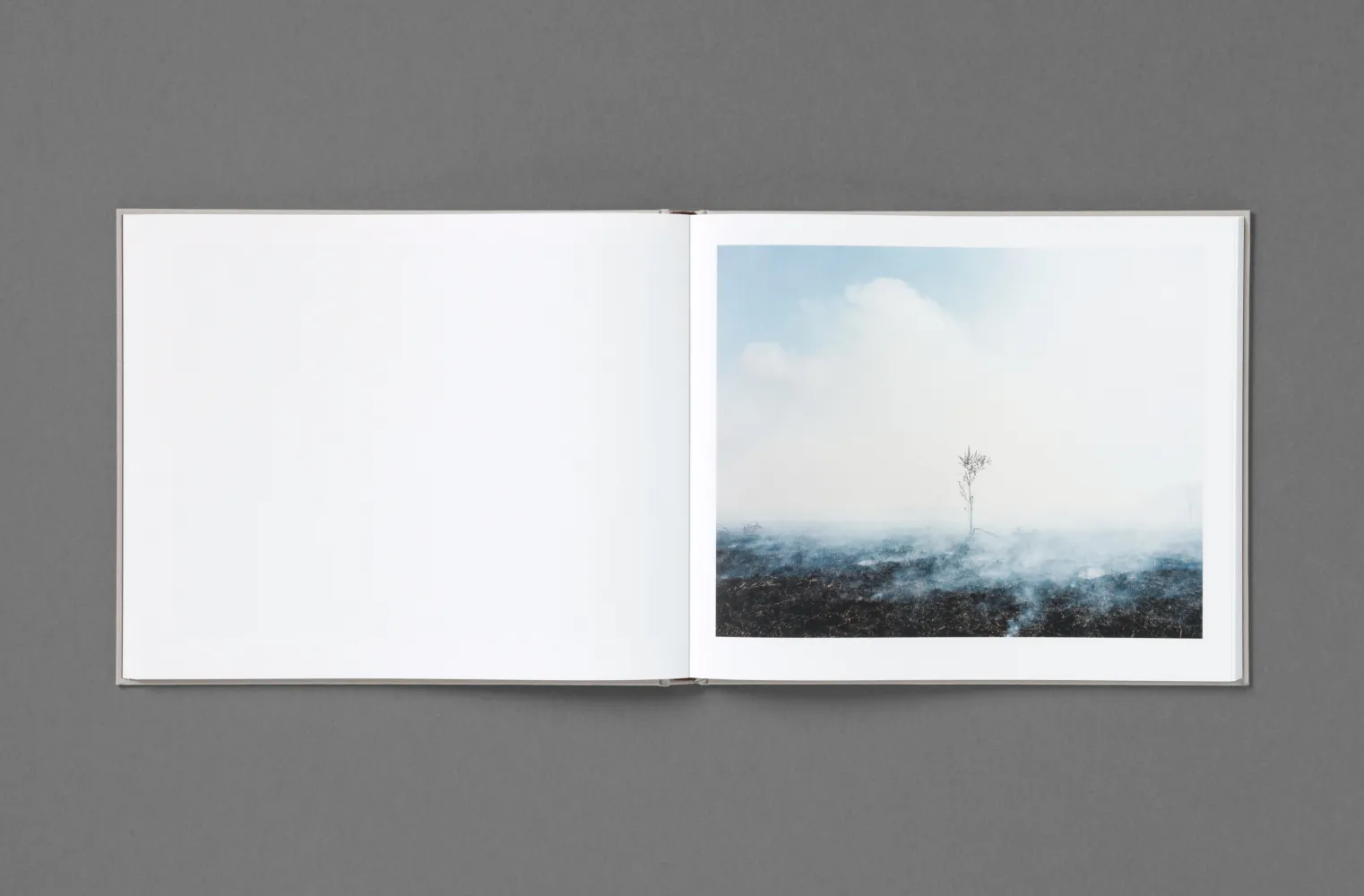

Khashayar Javanmardi's photobook Caspian documents the environmental devastation along the Iranian coastline. More than just a record of decline, Caspian is a powerful meditation on loss, ecological destruction, and the deep bond between people and place. Drawing from his personal connection to the sea, where he travelled to every summer as a child, Javanmardi has created a body of work that blends poetic sensitivity with a sharp activist edge. The photographer explores deterioration and climate change that have stripped the region of its vitality, leaving lasting scars on both the landscape and the communities that depend on it.

How fortunate I was to grow up on the shores of the world’s largest lake. How blessed to have spent my youth dreaming of its endless blue sky, of swimming in its gentle waves. But now I wonder, am I fortunate enough to see it smile once more?

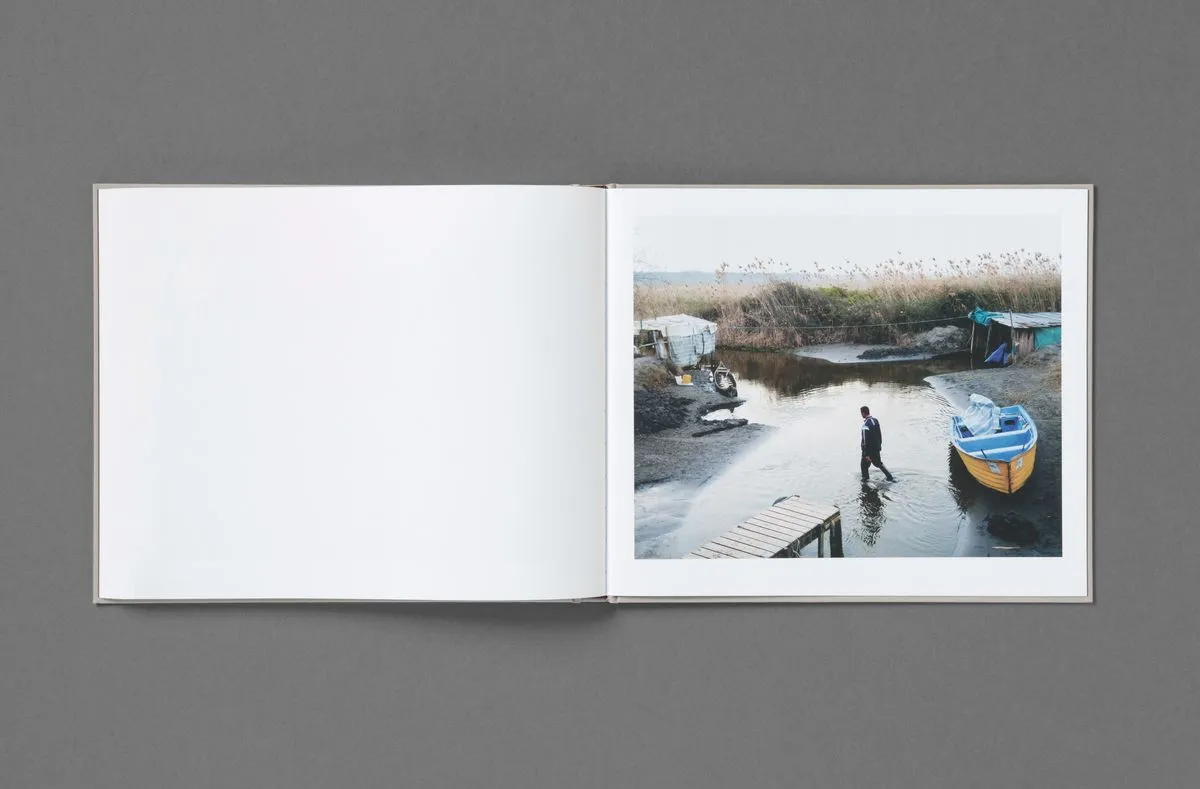

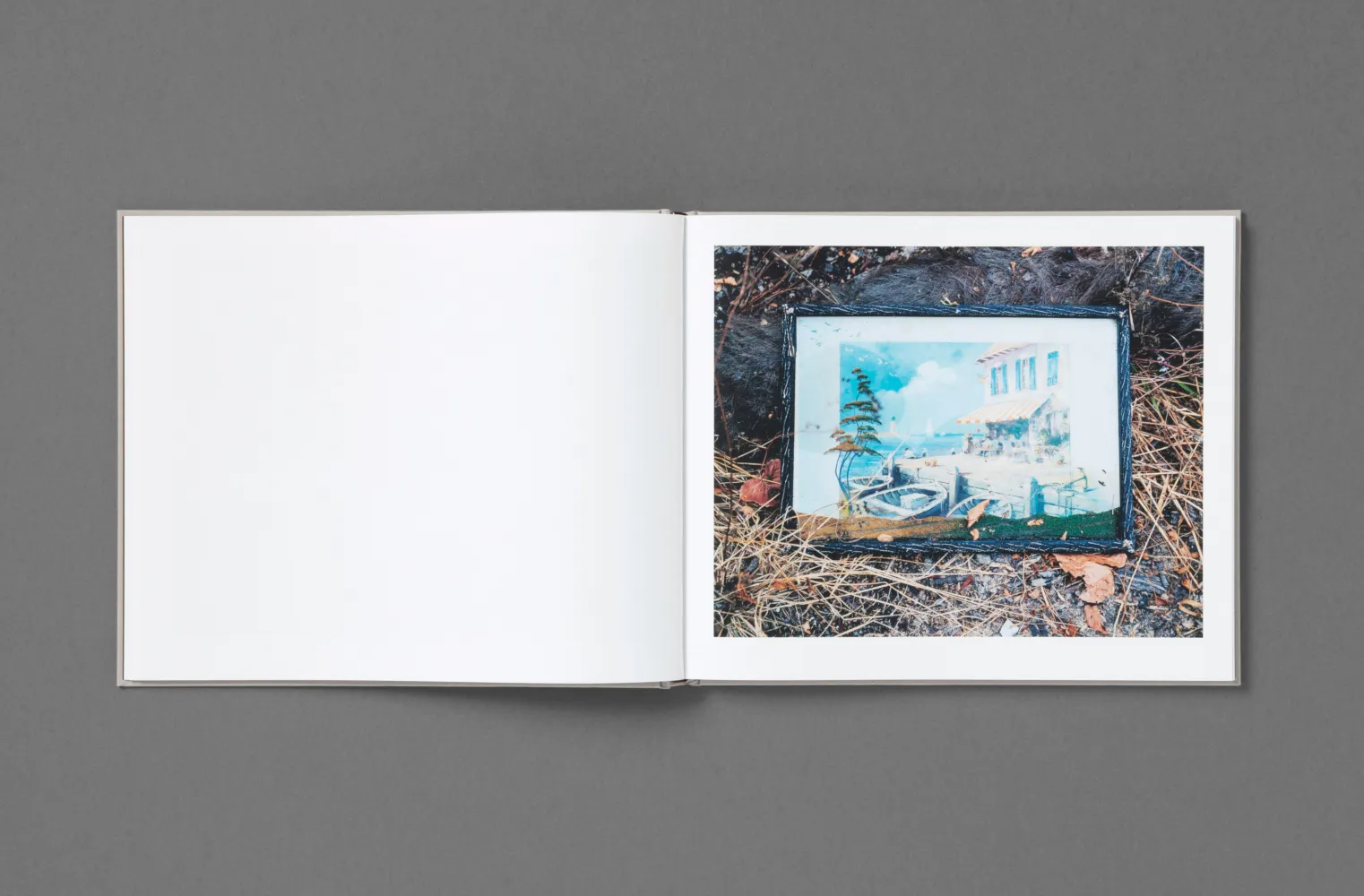

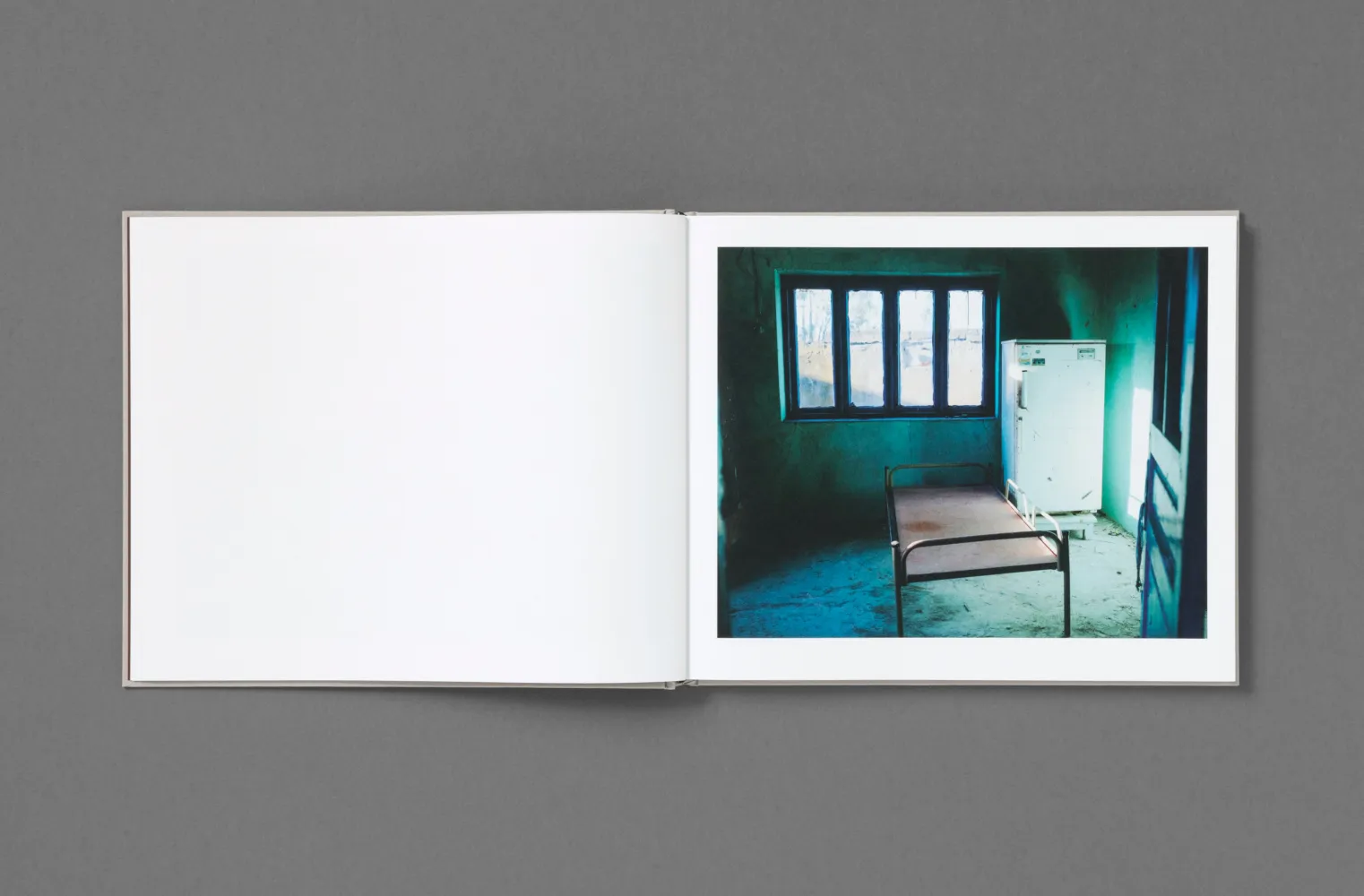

The Caspian Sea serves as both a symbol and a reality of environmental catastrophe. Javanmardi’s images are steeped in the melancholy of this decline, bearing witness to its effects on the sea and its surrounding communities. In one striking image, a group of boys bathing in the tranquil waters offers a moment of serenity, a fleeting sense of timelessness. Yet, this contrasts with other photographs in the book—scenes of desolate landscapes, rusting boats, and abandoned houses—all signaling a broader story of degradation. The juxtaposition of these images underscores the tension between human joy and the pressing environmental reality that threatens to wipe it away, while also revealing the traces of a once-thriving era now lost.

This body of water, this vast inland sea, has no outlet, no escape from the poisons we pour into it. Its life is bound up with ours; as it withers, so do we. As it sickens, so too do we fall ill. There is no separation between its fate and ours, except perhaps in the love and compassion it still seems to hold, which we, for all our arrogance, seem to have lost.

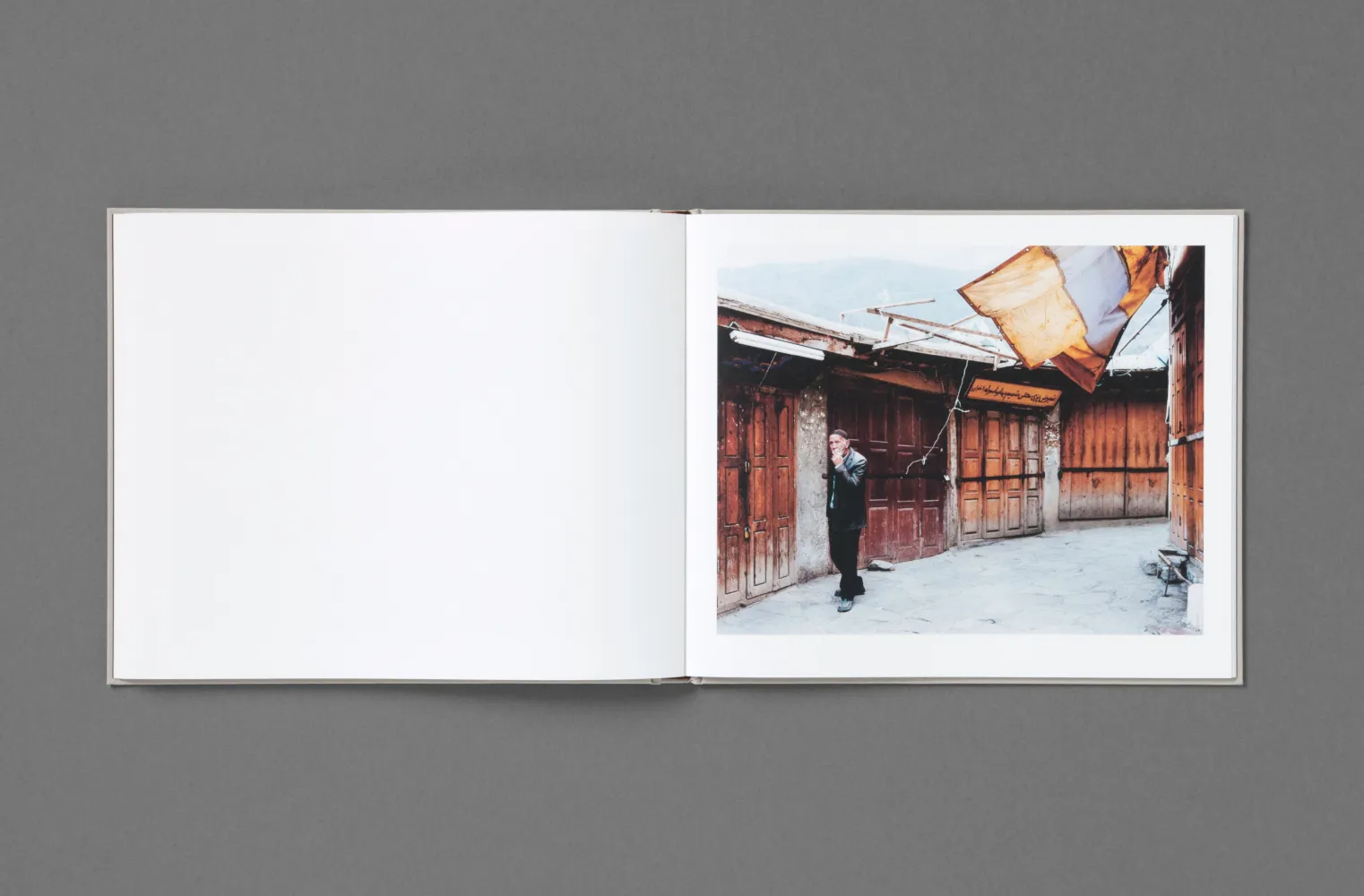

What sets Caspian apart is Javanmardi’s ability to marry the atmospheric with the documentary. His photographs evoke a sense of place that is both personal and political. While the sea may be a site of childhood nostalgia, it has also become a battleground where the consequences of human activity are starkly visible. Industrial waste and sewage have poisoned the water, leading to a 70% reduction in the local fishing industry, devastating livelihoods. The water level is evaporating due to climate change, pollution, and waste, while the overexploitation of both land and sea is wreaking havoc on its ecosystems and communities.

Javanmardi’s photographs capture this reality without sensationalism; instead, they are infused with a quiet, urgent sadness that demands attention. His color palette, often muted and restrained, reflects the somber mood of a land struggling under the weight of environmental neglect.

The book’s narrative unfolds in layers, revealing not just the ecological damage, but the emotional toll it has taken on the region’s inhabitants. From the fishermen whose nets come up empty to the villagers who witness their environment slowly decay, there is a palpable sense of anxiety and loss in their eyes. Javanmardi’s approach is respectful and distant—he doesn’t intrude on their pain, but he makes it impossible to look away. The subtlety of his compositions amplifies the gravity of the situation, making the viewer feel both a witness and a participant in this shared crisis.

In his accompanying text, Javanmardi reflects on the profound emotional and ecological loss surrounding the Caspian's decline. His reflections are personal, emotional, and evocative, weaving together memories of childhood spent on the Caspian Sea's shores with the harsh realities of its current state of decline. Through a blend of nostalgia and sorrow, he draws intimate connections between the fate of the sea and the lives of those who depend on it, suggesting that this environmental destruction is not just a physical catastrophe but a spiritual one as well. Though his reflections are tinged with sadness, there remains a quiet hope for the Caspian, a longing for its return to vitality, however distant that may seem.

For me, this story is one of love, even if, like all great loves, it carries within it the seeds of inevitable sorrow.