Exhibition view It's All Work. Women between Paid Employment and Care Work, Fotoarchiv Blaschka 1950-1966. Copyright: Universalmuseum Joanneum/J.J. Kucek

Exhibition view It's All Work. Women between Paid Employment and Care Work, Fotoarchiv Blaschka 1950-1966. Copyright: Universalmuseum Joanneum/J.J. Kucek Over the years, I've come to associate autumn with work—it is, after all, the season of new beginnings and the return to routines after the summer. This year, the Kunsthaus and the History Museum in Graz seem to echo that sentiment. Across their venues, two engaging displays delve into the meaning of work in all its dimensions—political, social, gendered, and ideological—featuring a rich array of archival materials and contemporary artworks

The exhibition at Kunsthaus Graz, 24/7: Work between Meaning and Imbalance, showing contemporary art that reflects on the meaning of work, is paired with a documentary show across the river at the History Museum, titled It's All Work: Women between Paid Employment and Care Work, Fotoarchiv Blaschka 1950–1966. A thematic connection between the two venues is reinforced by No Wonder, a video essay by Lia Sudermann and Simon Nagy, which is featured in both locations. Using the Fotoarchiv Blaschka as a visual framework, the video focuses on women's work, both paid and unpaid, and its dynamics of visibility and invisibility in public discourse. In a particularly thought-provoking segment, narrated by Lia, the video explores the invention of the 'housewife' and the immense workload women assumed with the dawn of industrialization.

The modern division of labour is an undercurrent at both venues against which different social and affective positions are tested. While work remains essential to the sustenance of society, the diverse modalities of its presence and absence from different social and political contexts emerge as a key point of investigation.

It's All Work features photographs from the rich Blaschka archive. Established by Egon Blaschka in 1947, Blaschka studio was run by his wife Erika after Egon became a journalist for Kleine Zeitung newspaper in the early 1950s. Although it is unknown who took which photo displayed in the venue, it is believed that many have been captured by Erika, who dedicated her time and work to the studio and was among the few women in the field dominated by men.

Unfolding over nine rooms, the exhibition examines different aspects of work and the tension between the paid, precarious, and unpaid work women in Styria undertook from 1950 to 1966. Some images present what is well-known—women working in their kitchens, taking care of children, and in other types of reproductive labour, while others highlight their position in the workforce, including in factories, laboratories, and offices. The show's first room reveals Eva Tropper and Astrid Aschacher's curatorial approach—a selection of images presented partly overlapping blurs the distinction between different aspects of women's work, where divides between paid/unpaid becomes indistinguishable. In many photos it could be both: women doing laundry, vacuuming, and feeding children. It's a tapestry of positions, questions, and ideas that other rooms aim to entangle and highlight. They are designed as interactive workstations where thematic questions and statements guide visitors to engage more deeply with the politics of representation, the role of media, social norms and structures shaping women's presence and position in the workforce, and image production.

The Blaschka archive proves decisive in this endeavour, with the contrast between published and unpublished work revealing deep-rooted attitudes about women's position in the workforce and society. A telling example is a photo sheet from a feature on rescue jumpers, showing both a man and a woman in this role. The newspaper decided to publish the photo of the man depicted in full professional gear, while the woman's portrait is cropped to show only her face, erasing any visual markers of her profession. To address this omission, a full portrait of the woman is displayed on the museum's wall, proudly reclaiming her status after decades of obscurity, also underscoring the complex journey of a story from concept to publication and exposing deeply rooted gender biases in representation.

With its engrossing design, It's All Work encourages interactive learning and critical exploration of women's work and the ways it shaped Austrian society, although the wealth of information often detracts from the aesthetic appreciation of the displayed images. The show's strength lies in its seamless integration of published and unpublished imagery and information, highlighting women's labor in Styria—a long-overdue focus, as noted by the curators—while emphasizing the work's centrality in the Blaschka archive. It offers a compelling critique of visual memory, exposing how different power dynamics shape hegemonic narratives while erasing others and questioning, at the same time, the concept of productive work in modern society.

While drawing attention to an often-overlooked aspect of Austrian social history and the work of Erika Blaschka, who remained unknown up until recently, the exhibition could have also benefited from a stronger intersectional perspective—for instance, by examining the experiences of migrant and upper-class women within this context. However, such perspectives may have fallen outside the scope of the archive on which the exhibition is based.

In the Kunsthaus, the understanding of labour expands to include contemporary modes of immaterial or intellectual work in a post-industrial society that everyone performs for big companies for free, as shown in Sebastian Schmieg and Silvio Lorusso's Five Years of Captured Captchas (2017).

The duo documented every CAPTCHA prompt they solved over five years, capturing screenshots of each and compiling them into five leporello books spanning approximately 90 meters. This is combined with an email the artists sent to Google, specifying the amount of work they did for the company (as it turns out, the prompts were used for digitizing books and training AI, among others) while seemingly only confirming they are not bots. Being used by a non-human intelligence and doing work without any acknowledgment, let alone remuneration, is among the newest forms of work exploitation perpetuated by big tech companies daily, and using millions of unaware workers. Similar in attention to the digitalized world is the work by Elisa Giardina Papa, Labour of Sleep, Have you been able to change your habits??, 2017, which critiques data mining as another form of labour imposed through digital apps used by people while resting.

As the exhibition 24/7 demonstrates, work has long transcended traditional notions, formats, and tools. Artists—or art workers—are themselves implicated in contemporary modes of production and exploitation, and their labour is particularly addressed in the exhibition's catalogue. As Katja Praznik notes, 24/7 highlights "the contradictions of work between meaning and imbalance," with art workers serving as "one of the best embodiments of this antinomy." They are presented as "model workers for neoliberal entrepreneurial rationality," encapsulating the precarity and paradoxes of contemporary labour. This neoliberal rationality is examined through a broad spectrum of approaches and reflections in mediums ranging from more traditional, such as painting, to installations, video art, assemblages, and mix-media installations.

This starts already in the long tunnel that takes visitors to the museum's first floor. Its walls and ceiling are covered in Peter Kogler's print Untitled (1992/2024), featuring large-scale images of ants, symbolizing the power of collective action. However, this power of the working class has been significantly undermined through its fragmentation and the terror of individualism that presides over contemporary neoliberal ideology. Art workers are just a segment of this totality that is tricked into and, at times, willingly participates in the Western ideology of art work not being work at all.

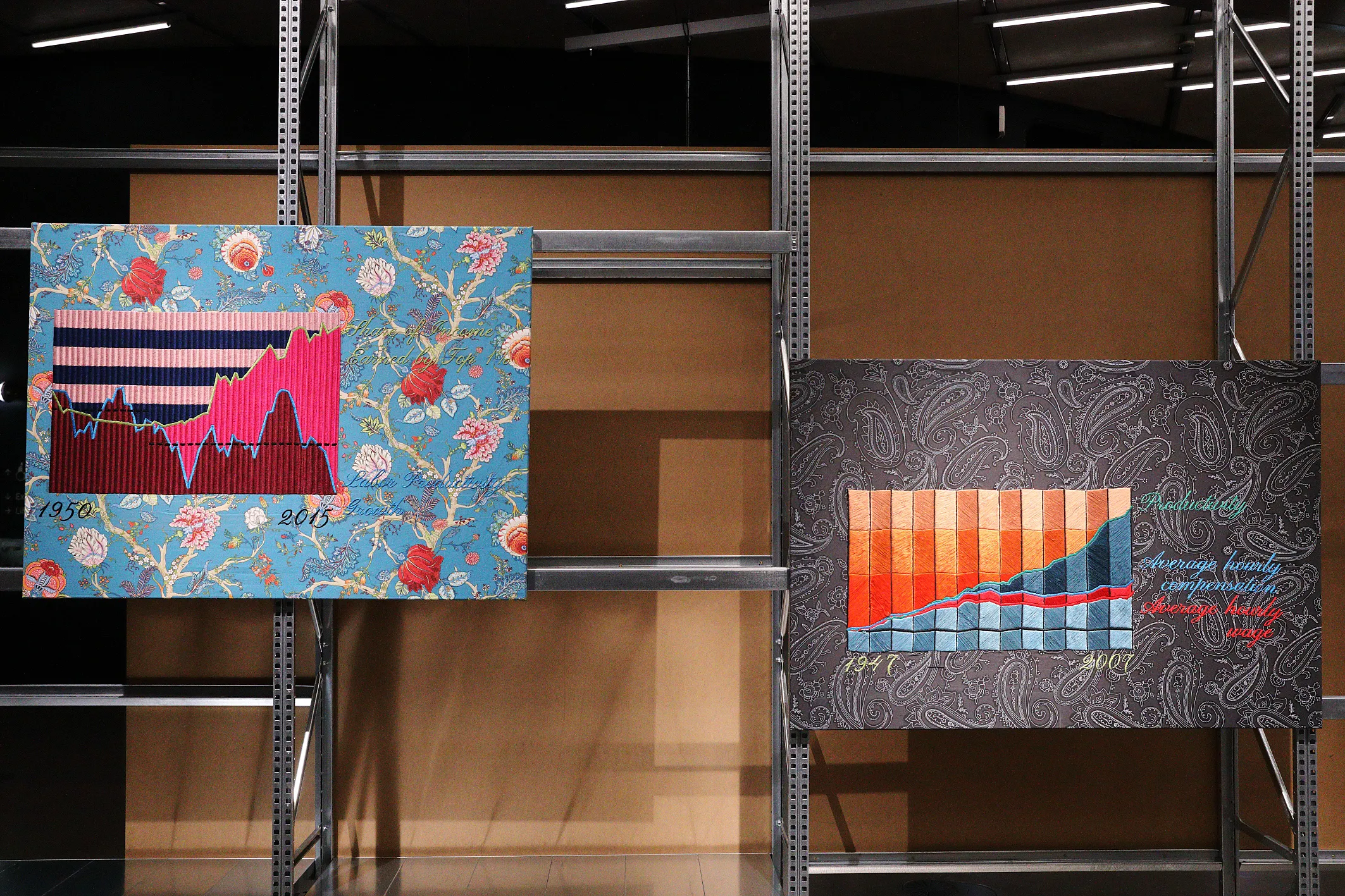

How collectivity and individuality intersect in a contemporary context, and how globalization influences labour, are the themes many artworks on view explore, including Maja Bajević's powerful video work Arts, Crafts and Facts, from 2015, accompanied by her embroidery of the same title from 2019, stitched with diagrams showing wealth distribution. The libretto featuring a choir from the artist's hometown sings about financial capital, its institutions, and its consequences on both the working class (with the loss of jobs on the periphery) and individual existence (in the increase of living costs). On the other hand, Oliver Walker's six-channel video One Euro (2015) makes visible the gross income disparities between the global North and South, showing how much time individuals spend working to earn one euro. While the video showing a CEO from the North lasts only one second, other videos run from a few minutes to over an hour.

Some artworks adopt an abstract formal language; among them is Liam Gillick's The Hopes and dreams of the workers as they wandered home from the bar (2005/2024), which greets visitors in the first segment of the show, in the form of a square on the floor made of red glitter, where only several footprints are discernable. Conceptual and formalist in nature, it captures an affective moment of workers' letting-go in bars and similar public spaces where collectivity and camaraderie could be asserted beyond the ticking clock measuring productivity.

Glitter, a material Gillick often uses, is fairy dust left behind by the workers who passed through the night, their footprints remaining a symbol of collectivism that dispersed with post-Fordism. Next to this work, a large photo by Andreas Gursky, Amazon, 2016, draws attention with its similar abstract quality, which reveals, on close inspection, a row upon row of packages waiting to be delivered with no workers in sight— a metastasis of consumer, mass society, in which Amazon's distribution centers are examples of its horror vacui.

While some works on view take aspects of reality distilled to resemble, formally, abstract artworks, others come in the forms of contemporary contraptions artists created to examine temporal aspects of labour.

These include Julien Berthier's The Clock of a Working Life, 2008, a machine that calculates individual time until retirement, and Sam Meech's Punchcard Economy: 8 Hours Labour, 2024, featuring a knitting machine used by the artist to knit a banner during an 8-hour working day in the museum, presenting the working process itself as an artwork (an interesting fact is that the artist was remunerated for this work in line with the Austrian Cultural Council's guidelines for fair pay).

A significant and also revealing aspect of the show are older pieces, including Tehching Hsieh's One Year Performance, 1980-1981, and Martha Rosler's iconic feminist critique of the naturalization of women's unpaid domestic work emerging from second-wave feminism, titled Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975. Hsieh's performance, documented in photos, involved punching a time clock installed in his apartment every hour on the hour for a year, highlighting the oppressive dynamics of work routines, while Rosler satirically demonstrates the use of kitchen tools.

The works actualize the position of illegal immigrants and sexual minorities in the workforce, making obvious class politics behind capitalist social formation that marginalizes and exploits individuals along different identity markers. Similar to Rosler's intention and also rooted in second-wave feminism is the video work AEG Vampyr 1400 (2017) by Selma Selman, showing the artist destroying vacuum cleaners in a gallery space.

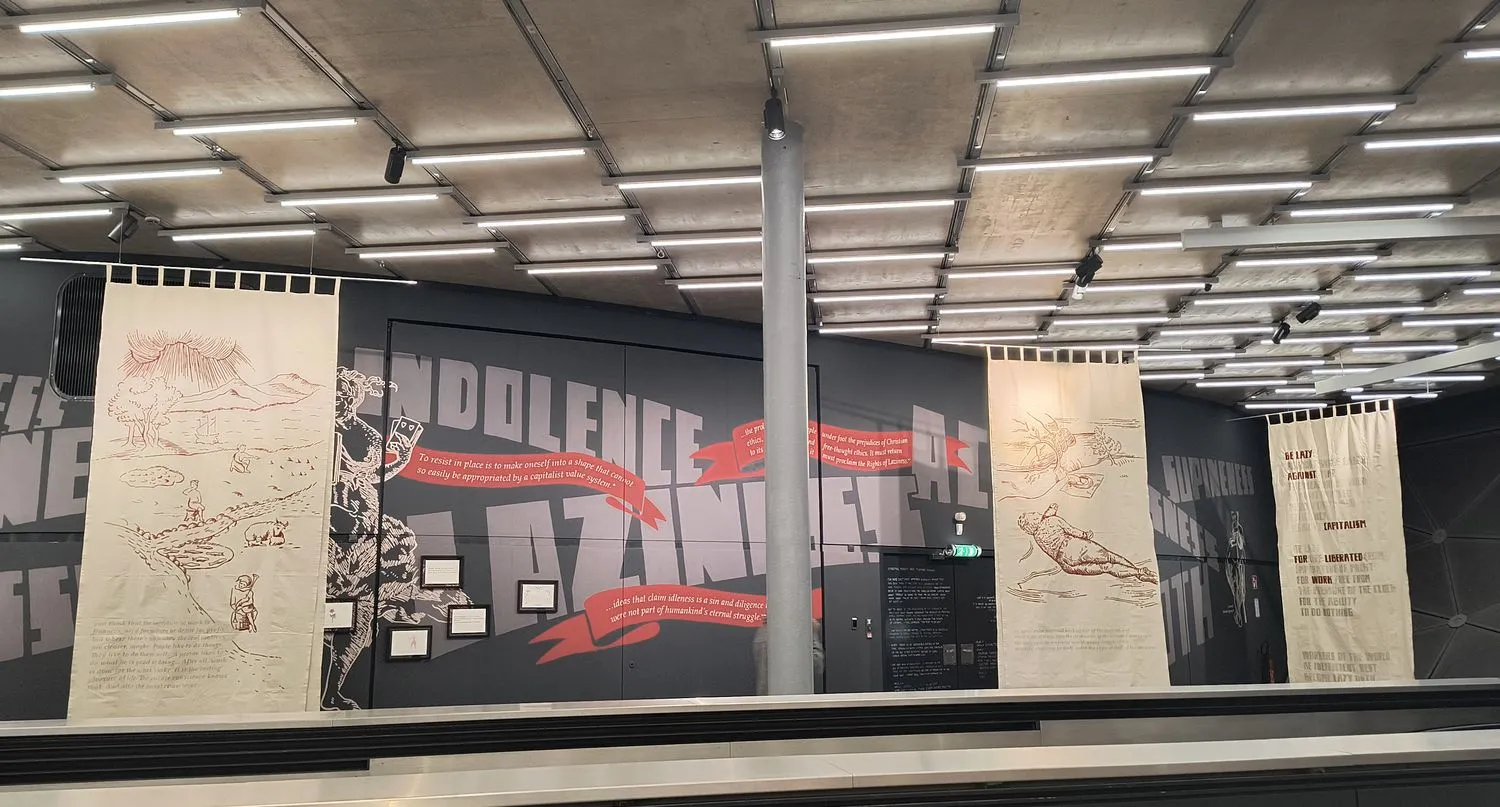

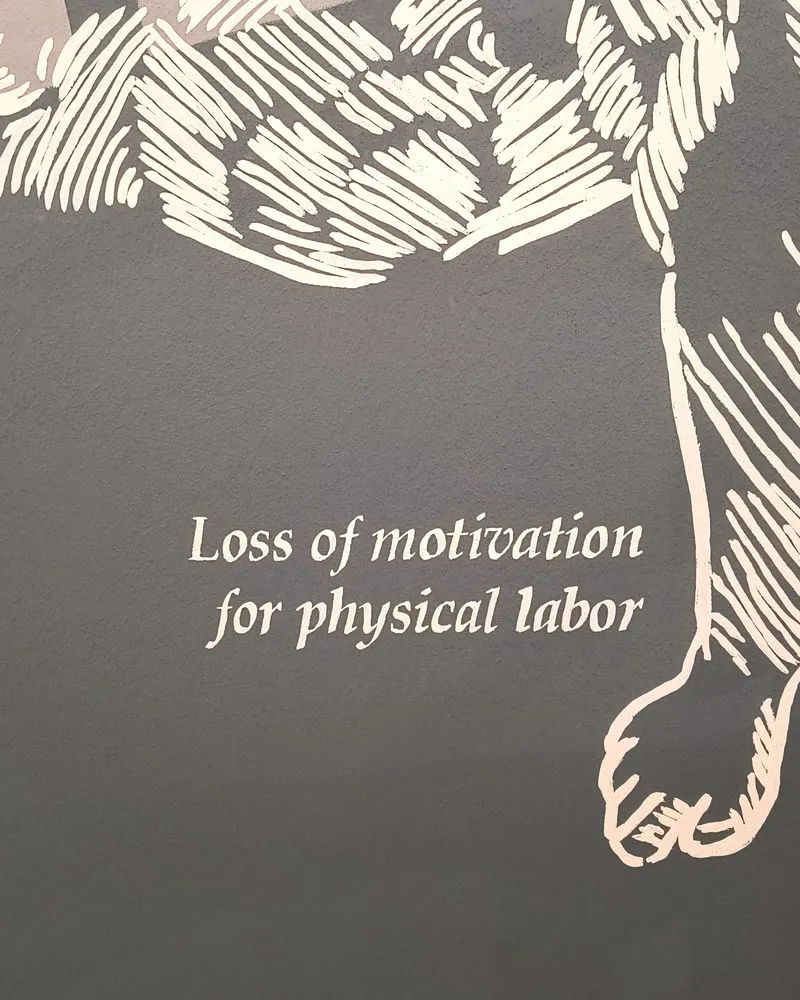

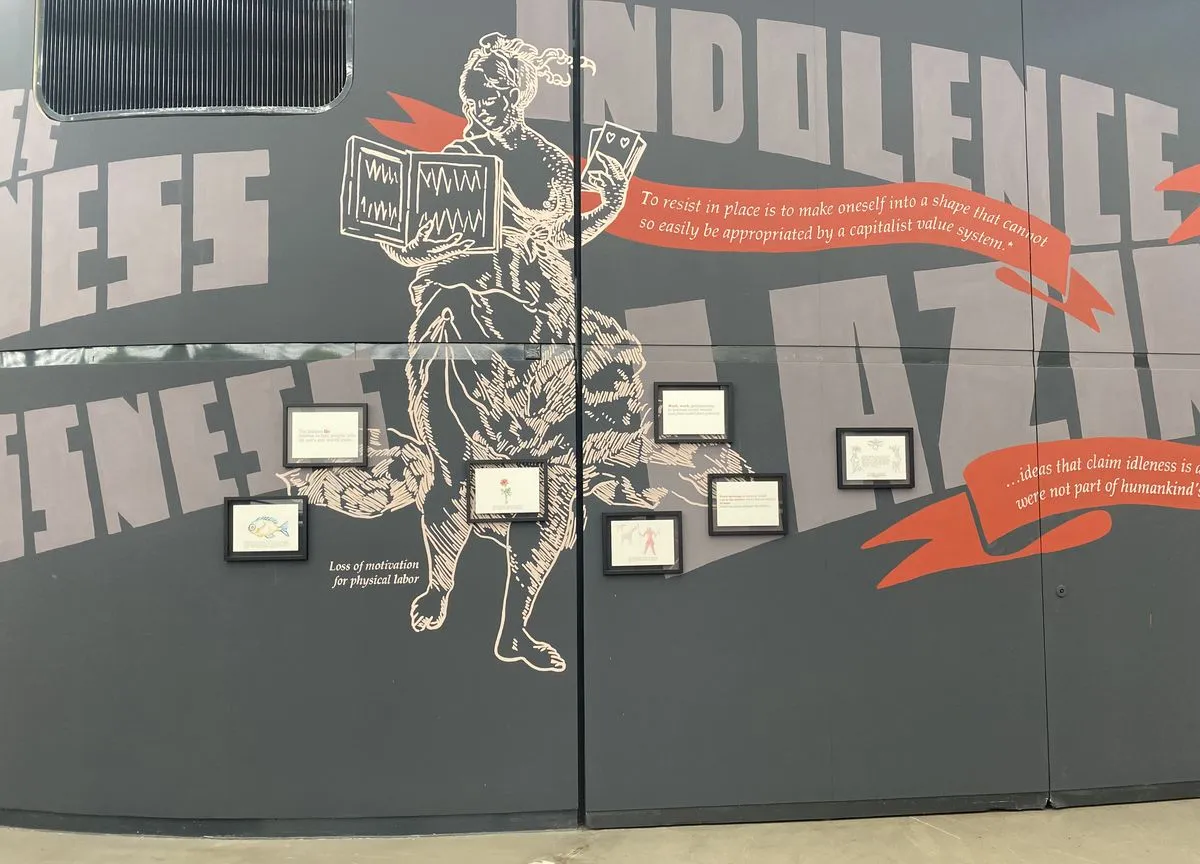

While workers' time is measured, remunerated, and commodified within the relentless expansion of capitalist accumulation, its ideological enemy comes in the forms known from child plays—Just keep on going (2015-ongoing) by Michail Michailov, although playful and lighthearted in showing the body's interactions with space, subtly references repetition and routine transposed from work to everyday life—and the concept and practice of leisure, but not in its touristic connotation, which perpetuates consumption-driven dynamics, but in the form of laziness, and all its ideological implications regarding productivity and value. The most powerful commentary on how to oppose the neoliberal capitalist machinery comes from the Serbian artistic duo KURS, comprised of Mirjana Radovanović and Miloš Miletić, and their large-scale multimedia work We have always received something in exchange that we lived. On Laziness, 2024.

After various contemplations on work in previous segments, KURS brings the idea of laziness and idleness as antidotes against exploitation and structural inequalities the neoliberal global order creates. Because what else to do when pressured to perform, than to perform oneself outside of the work norm, and to introduce, against the ticking clock measuring working hours, one that stands still? Through a series of narratives taken from historical sources that explore the concept of laziness, KURS creates an impressive tableau covering the entirety of a wall and large-scale textiles that bring these ideas more into focus.

There are segments of the show that seem to drift in space, between strong conceptual and political positions surrounding them. Those are tools of work, or objects linked to workers' spaces that seem uprooted without their human agents. These include Pia Mayrwöger's Mischmaschine (2021/2024), comprising a concrete mixer and concrete and Luisa Margan's Cache (2023/24), a ready-made installation of metal lockers inscribed with words wages, rent, and property in hand cream. Together, they are strong visual anchors and reposts from the overwhelming presence of video art at the show, demanding attention. Silent in contrast to sounds that come from different points in space, they are perhaps the most poignant elements that provoke thinking about what is left after the work is done, and how work shapes and builds our environments. The aesthetics of labour is grounded here, anchoring the exhibition in the material, palpable reality of work.

The journey through contemporary art that takes work as its inspiration and critique highlights artists' deep engagement with this central aspect of modern society. While the omnipresence of work and its role in shaping individual lives are foregrounded, its multiplicity of forms and the inequalities it engenders emerge as key points of contention. Curator Katia Huemer provides a thoughtful framework for navigating these positions and the historical contradictions of labour, culminating in the concept of laziness as a provocative political statement. While each artist focuses on their unique perspective, the collective body of work presents a critique of neoliberal capitalism, exposing its destructive processes of capital accumulation and the increasing subjugation of life to capital in the 21st century.

The exhibition 24/7: Work between Meaning and Imbalance at Kunsthaus Graz will be on view until January 19th, 2025, while It's All Work: Women between Paid Employment and Care Work, Fotoarchiv Blaschka 1950-1966 at the History Museum remains open until January 6th, 2025.