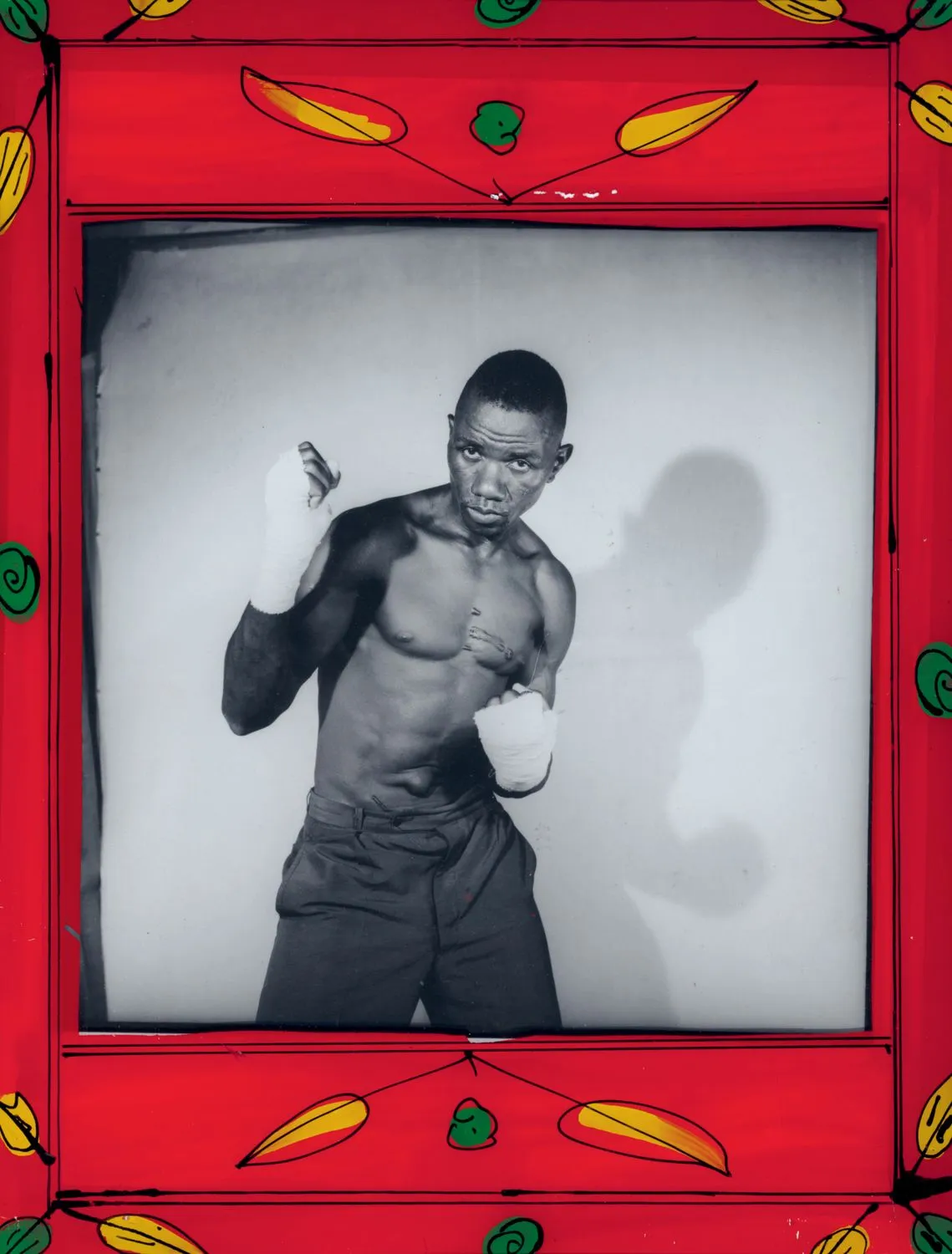

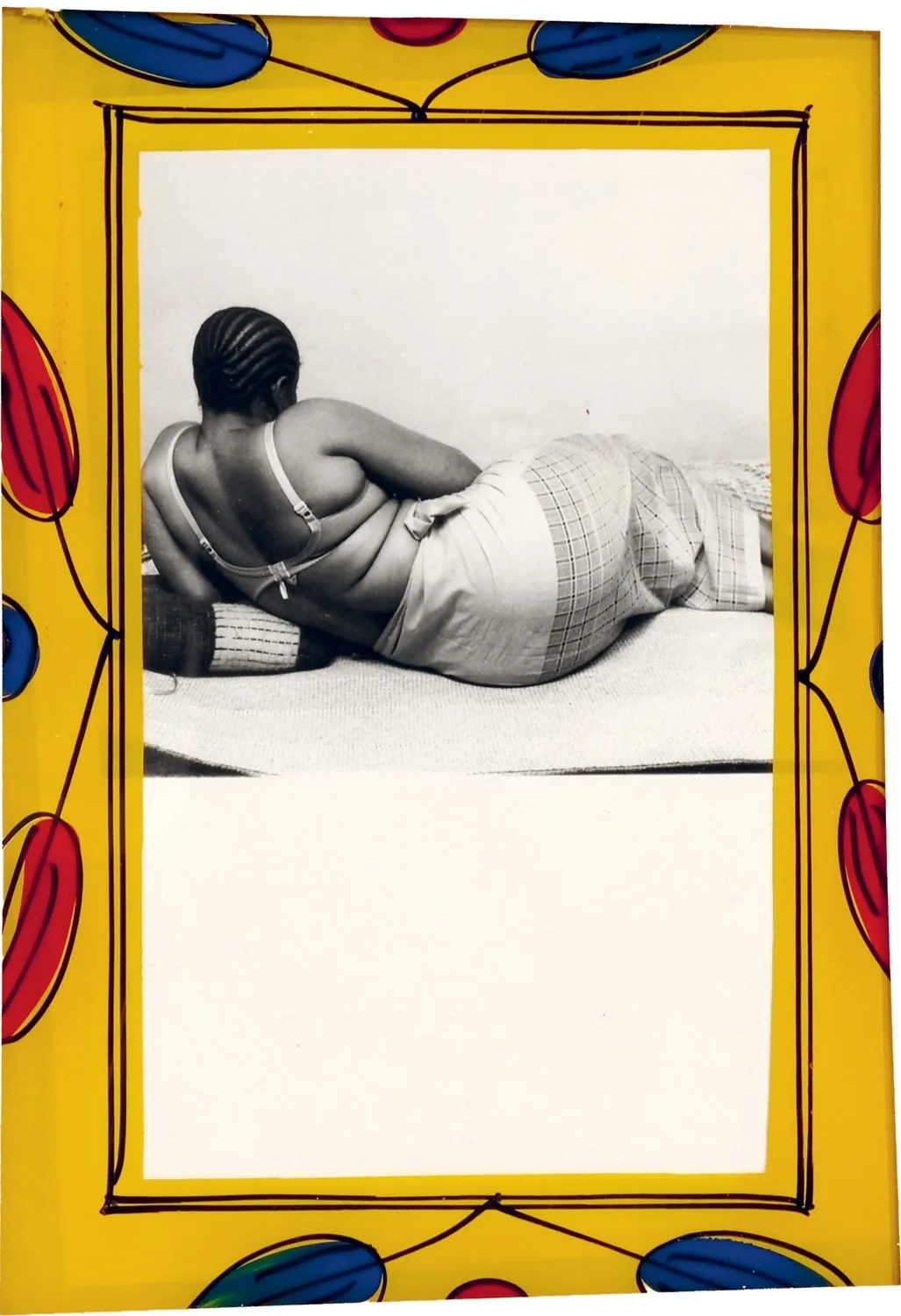

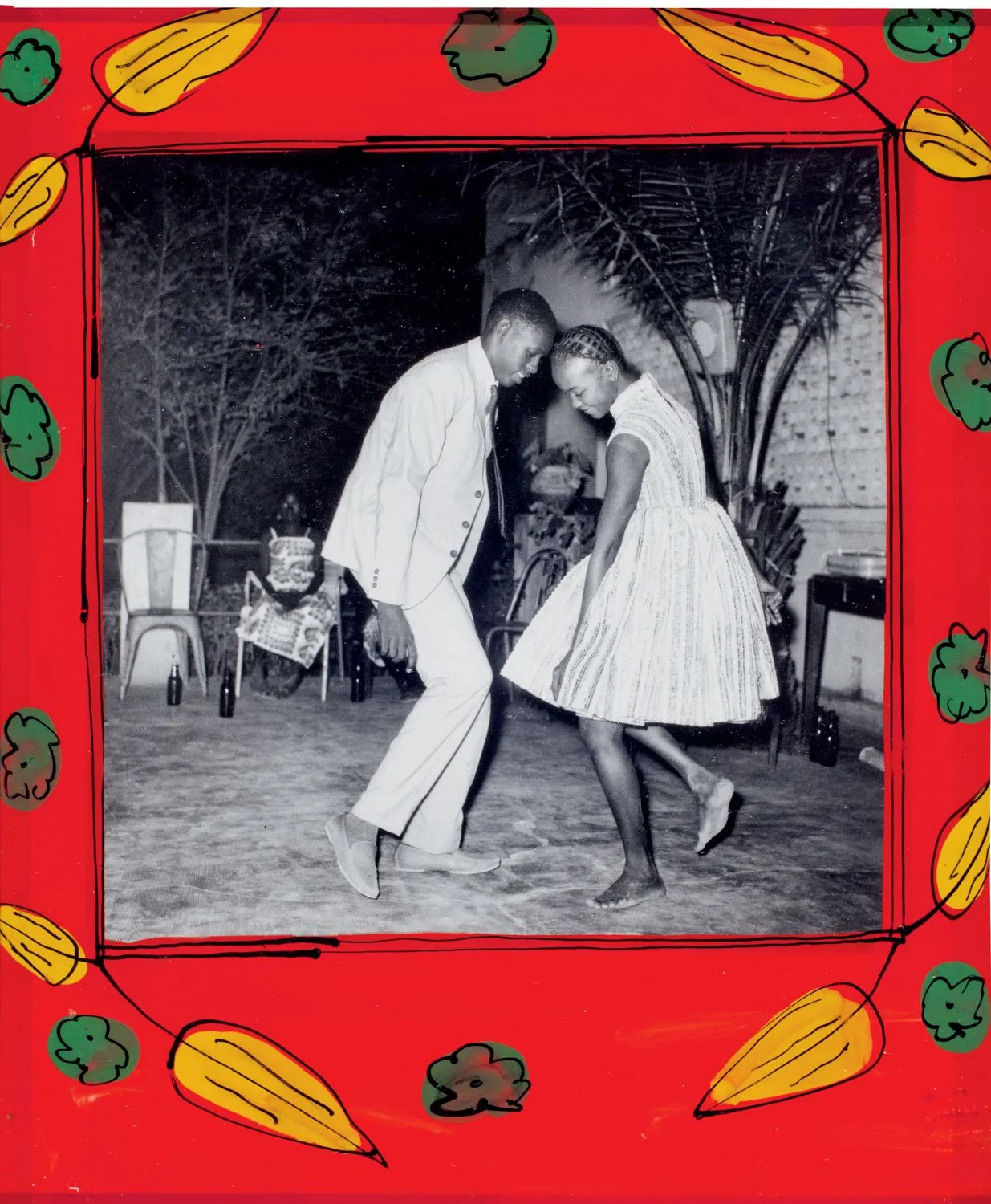

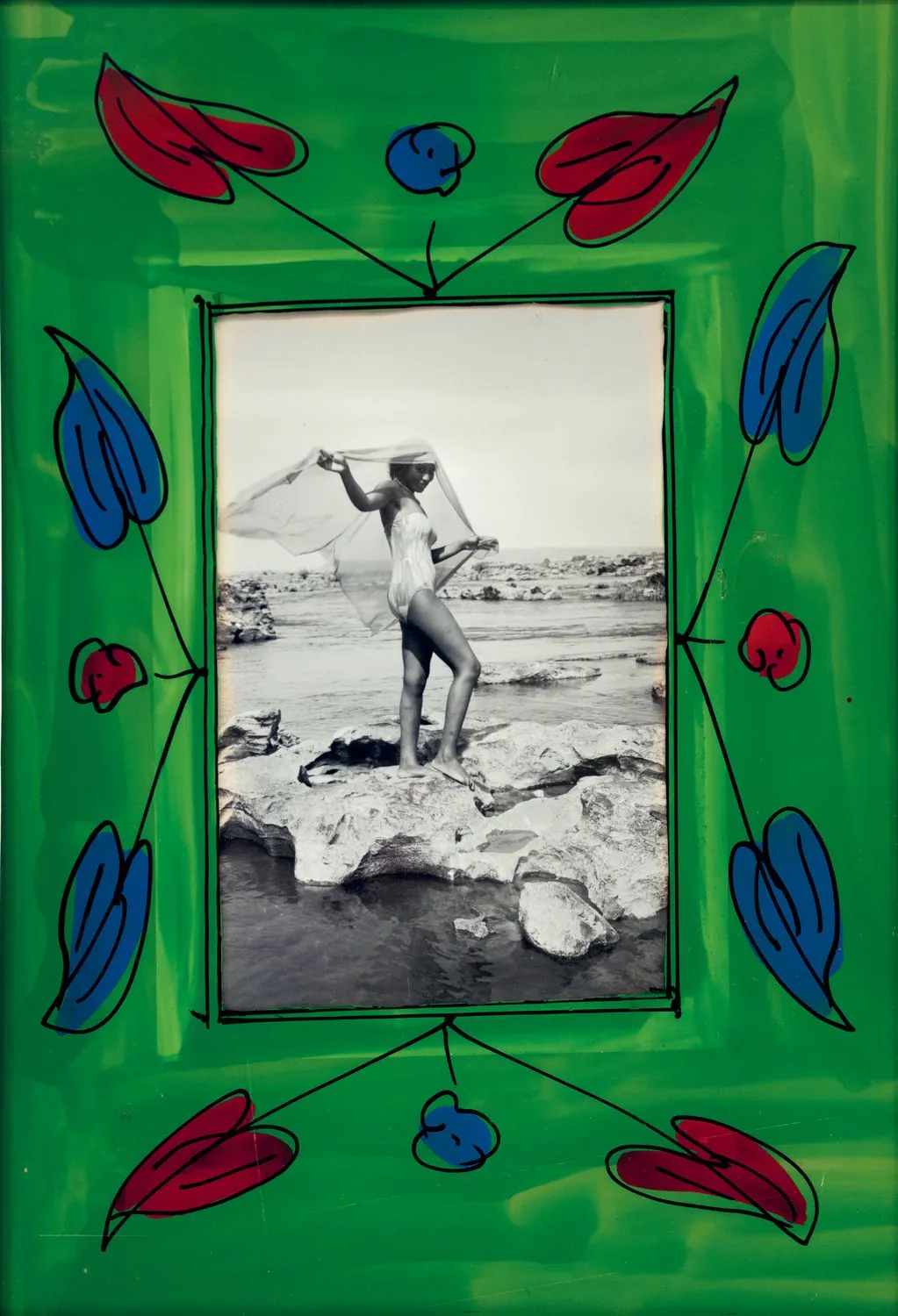

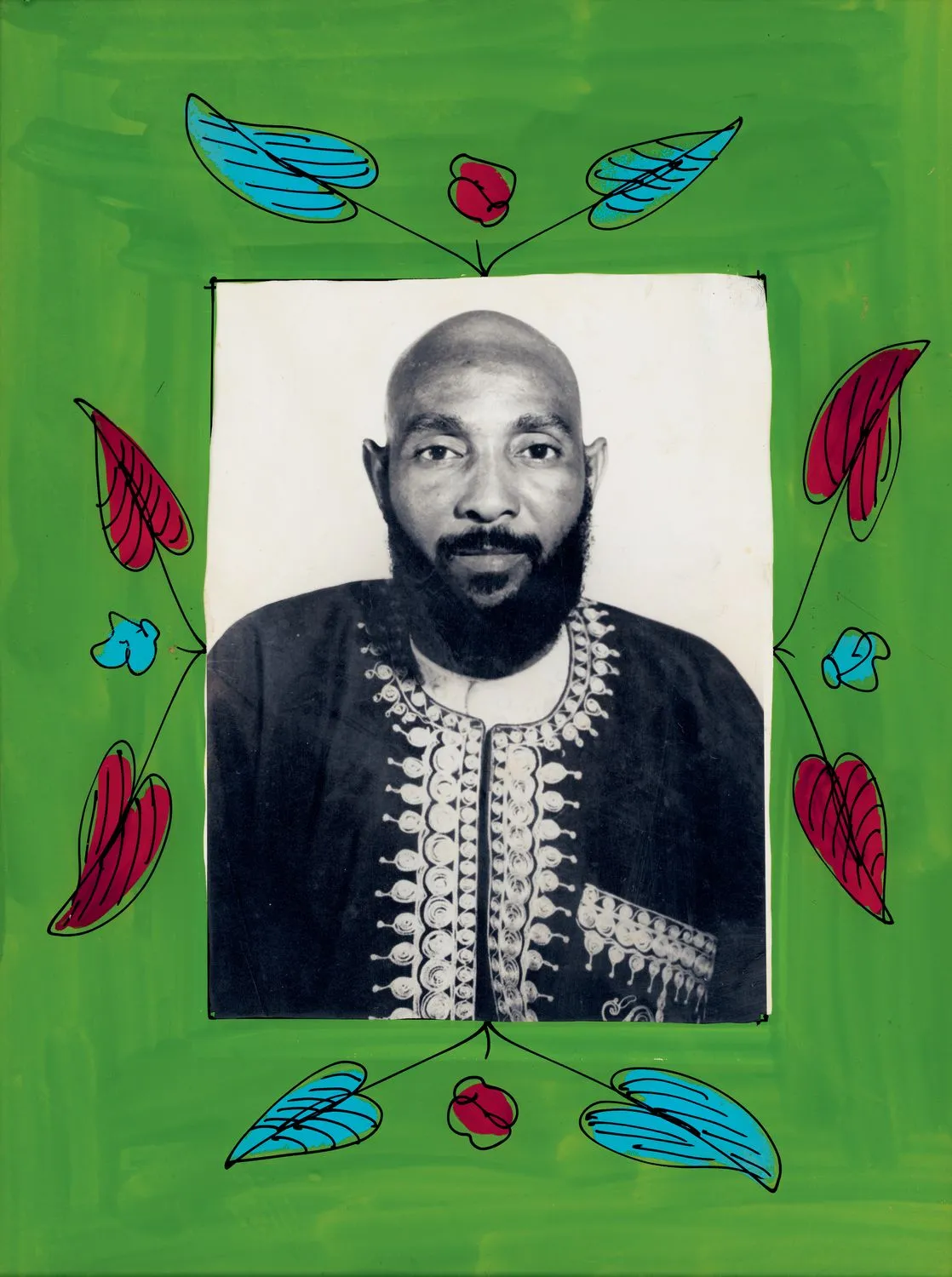

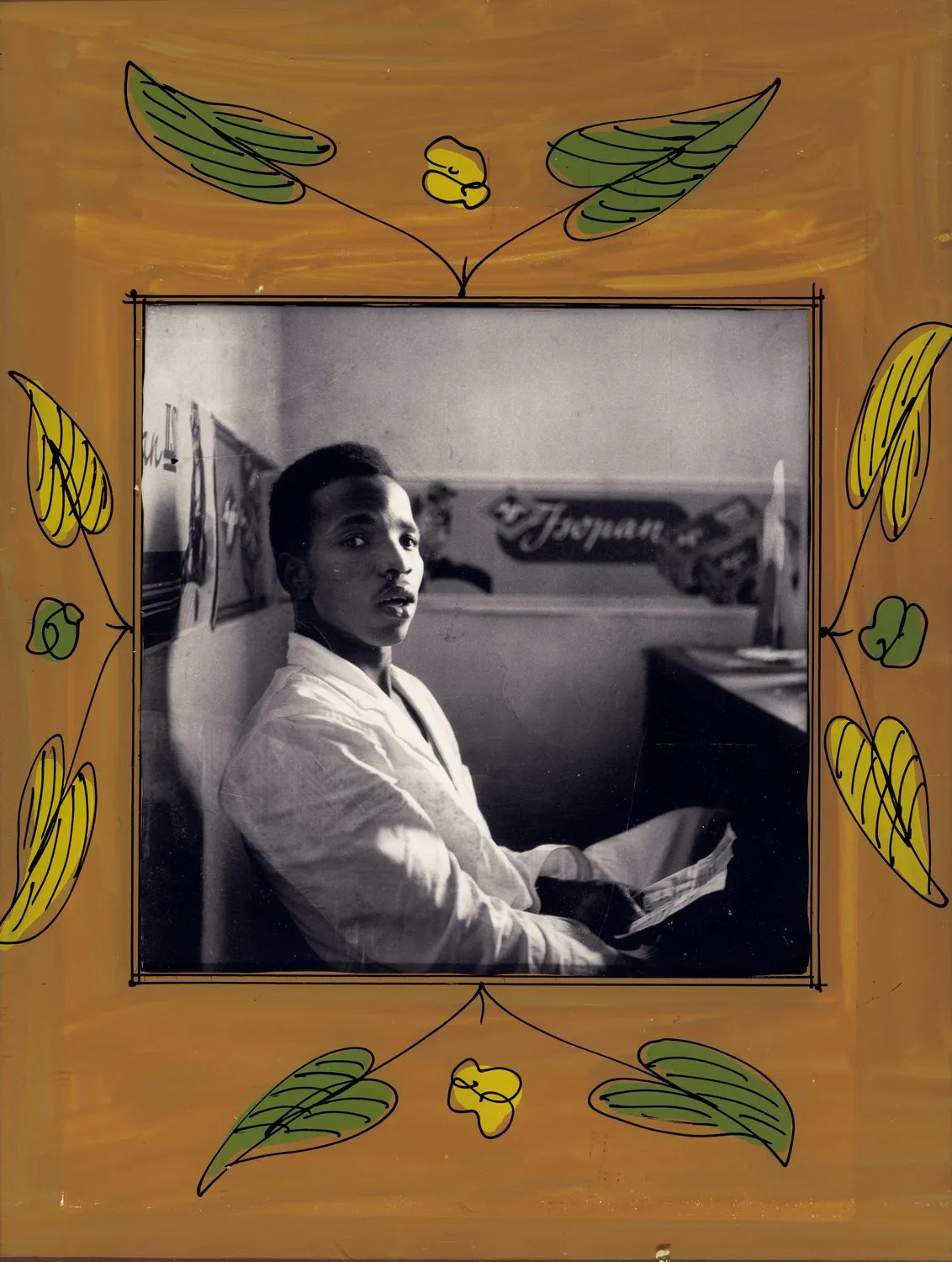

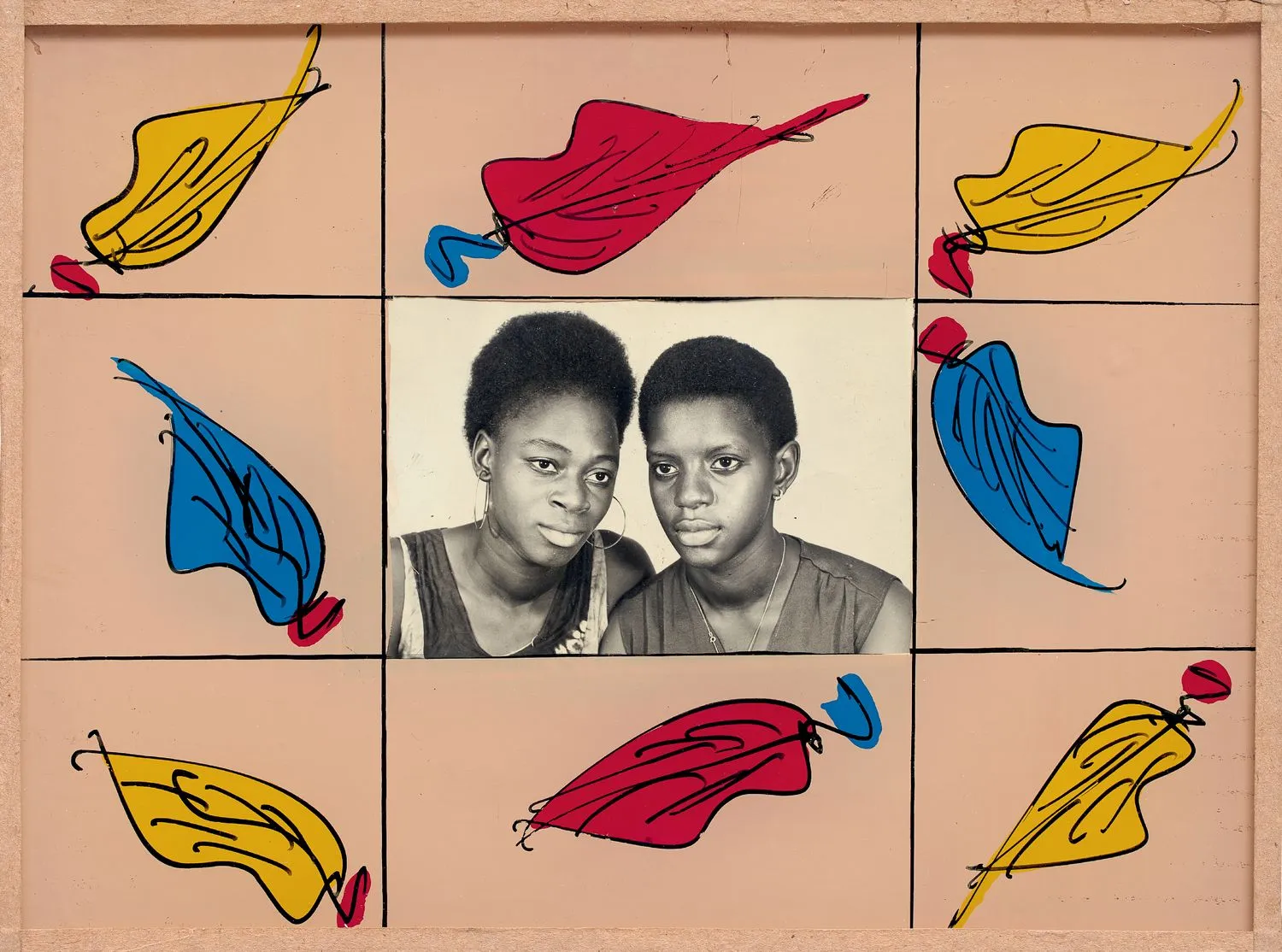

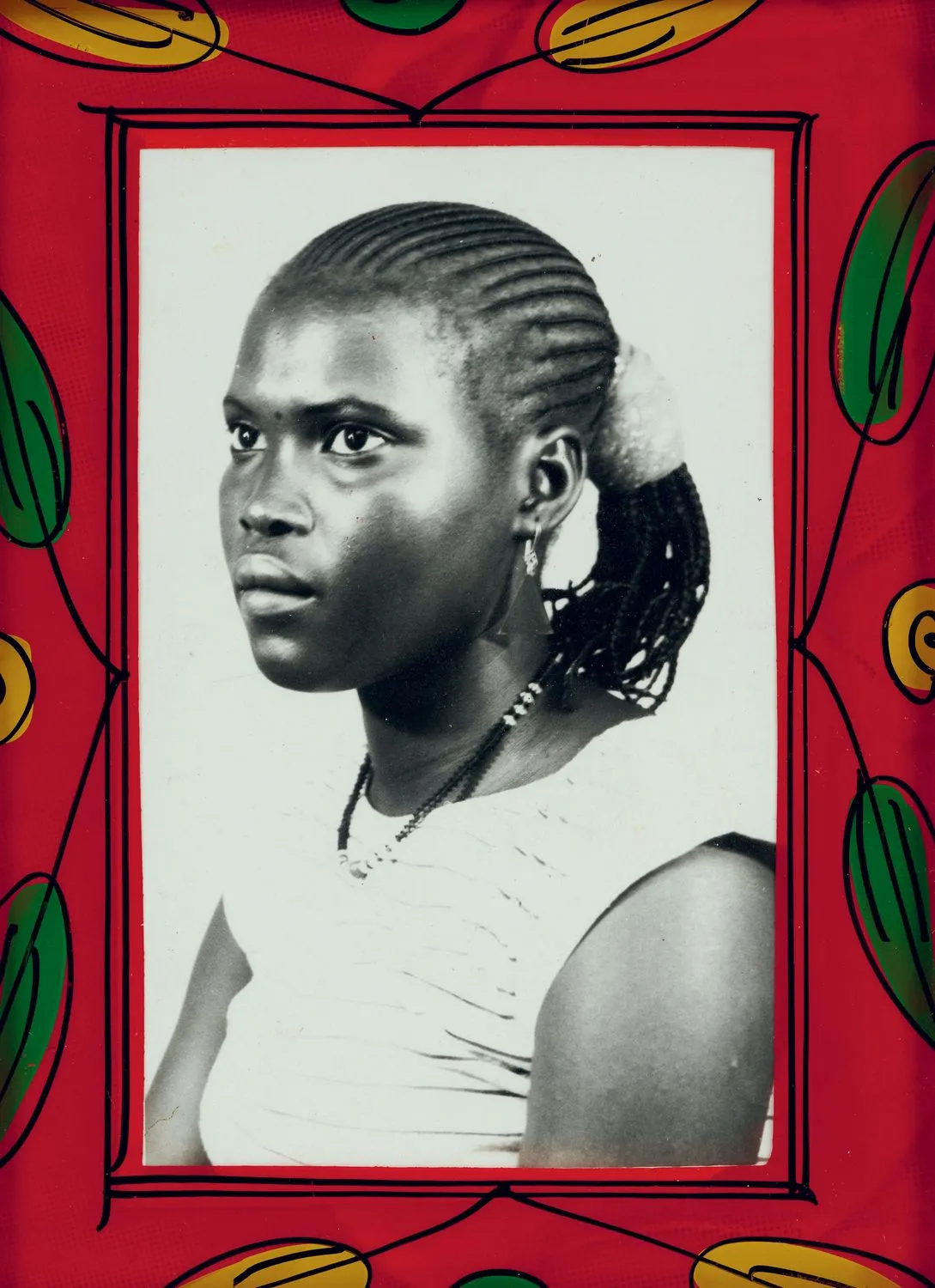

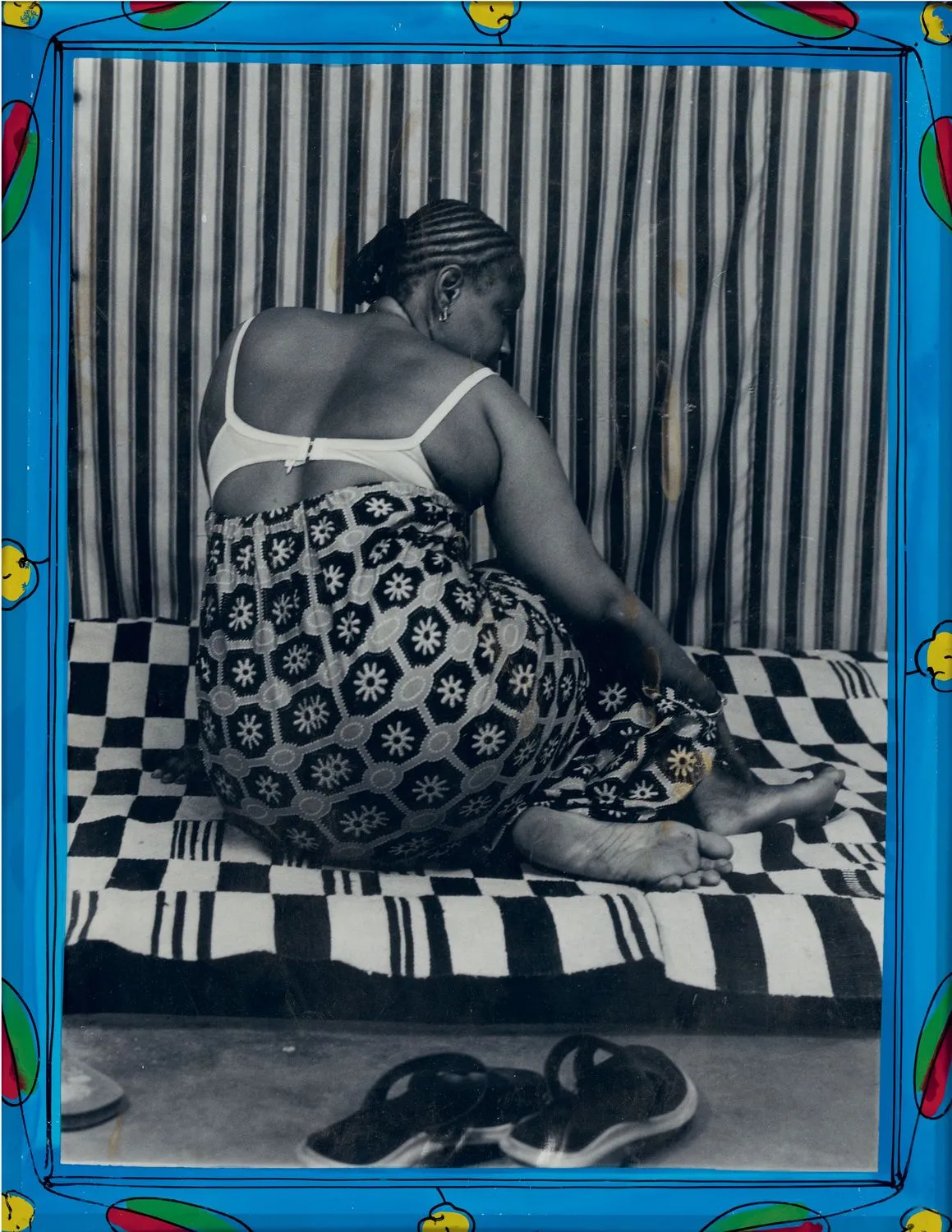

Malick Sidibé, Painted Frames, 2025 © Malick Sidibé 2025 courtesy Loose Joints

Malick Sidibé, Painted Frames, 2025 © Malick Sidibé 2025 courtesy Loose Joints In 1960, Mali emerged from 55 years of French colonial rule into a wave of nationalist hope. Independence brought palpable optimism to Bamako, where youth culture blossomed in a wave of renewal. The city's nightclubs pulsed with new rhythms, rock 'n' roll, soul, and Cuban sounds blending with African beats, while Pan-African ideals and liberation movements from across the Atlantic electrified the imagination. Self-expression became a political act, as a new identity was forged in real time.

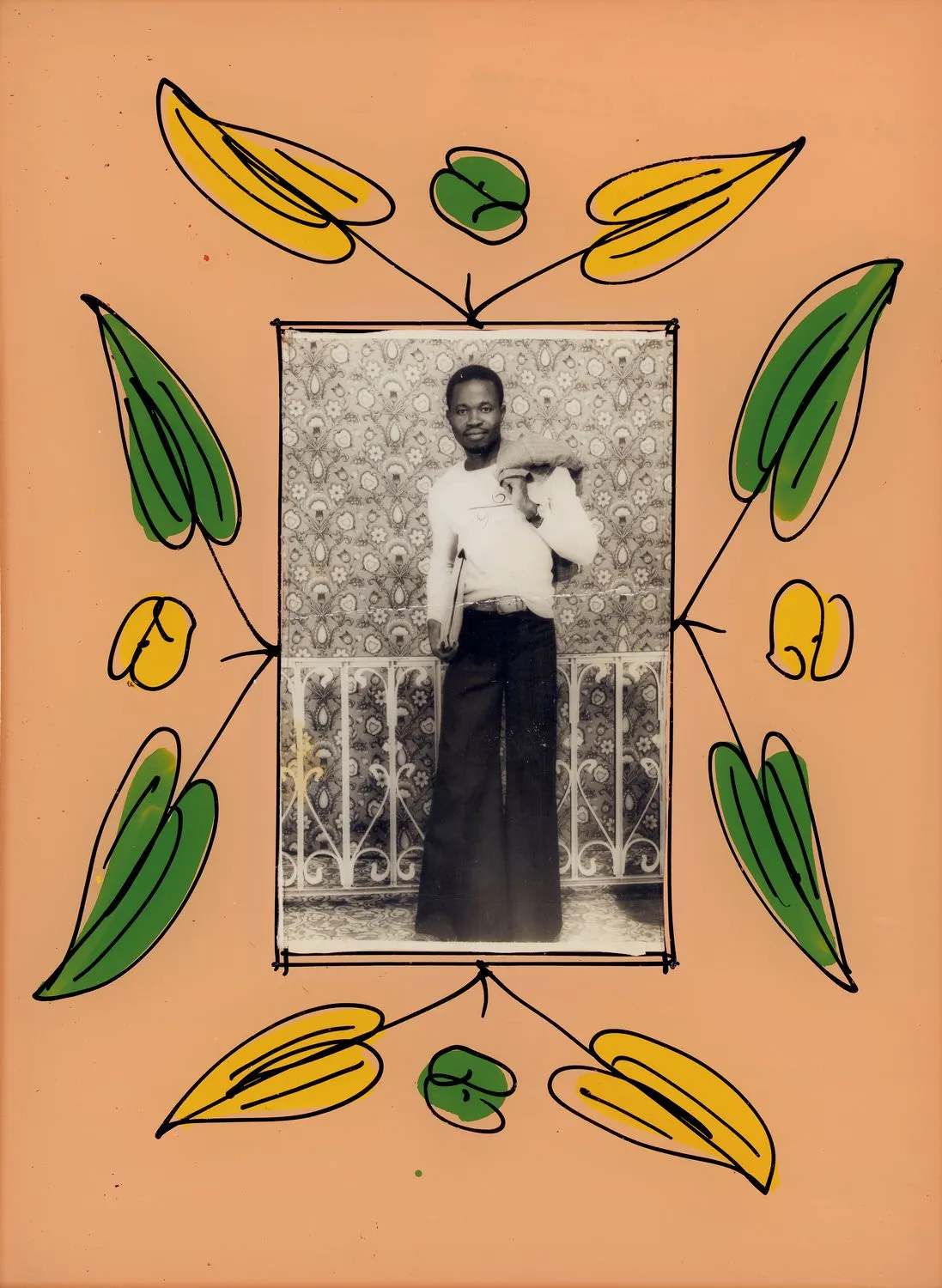

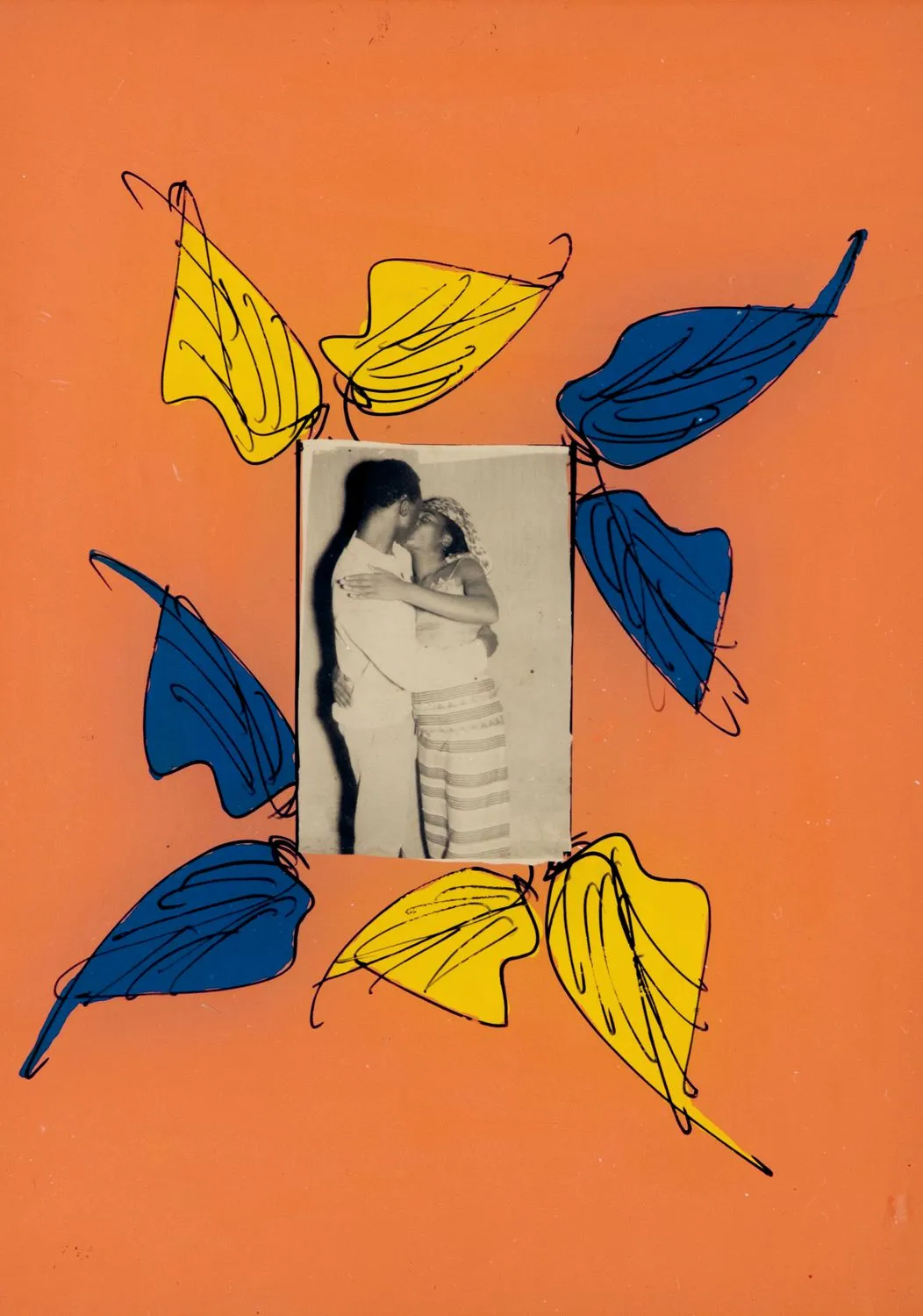

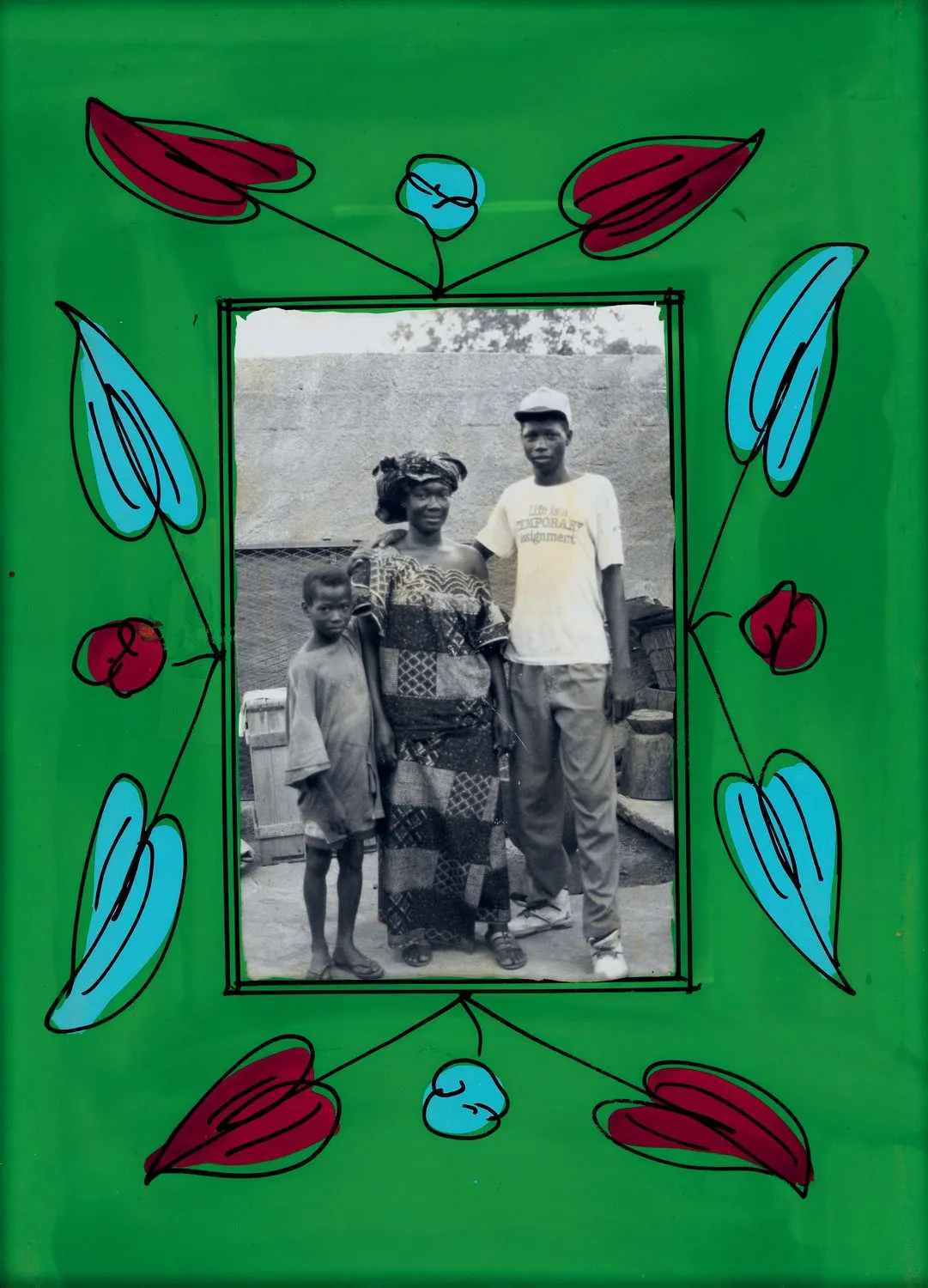

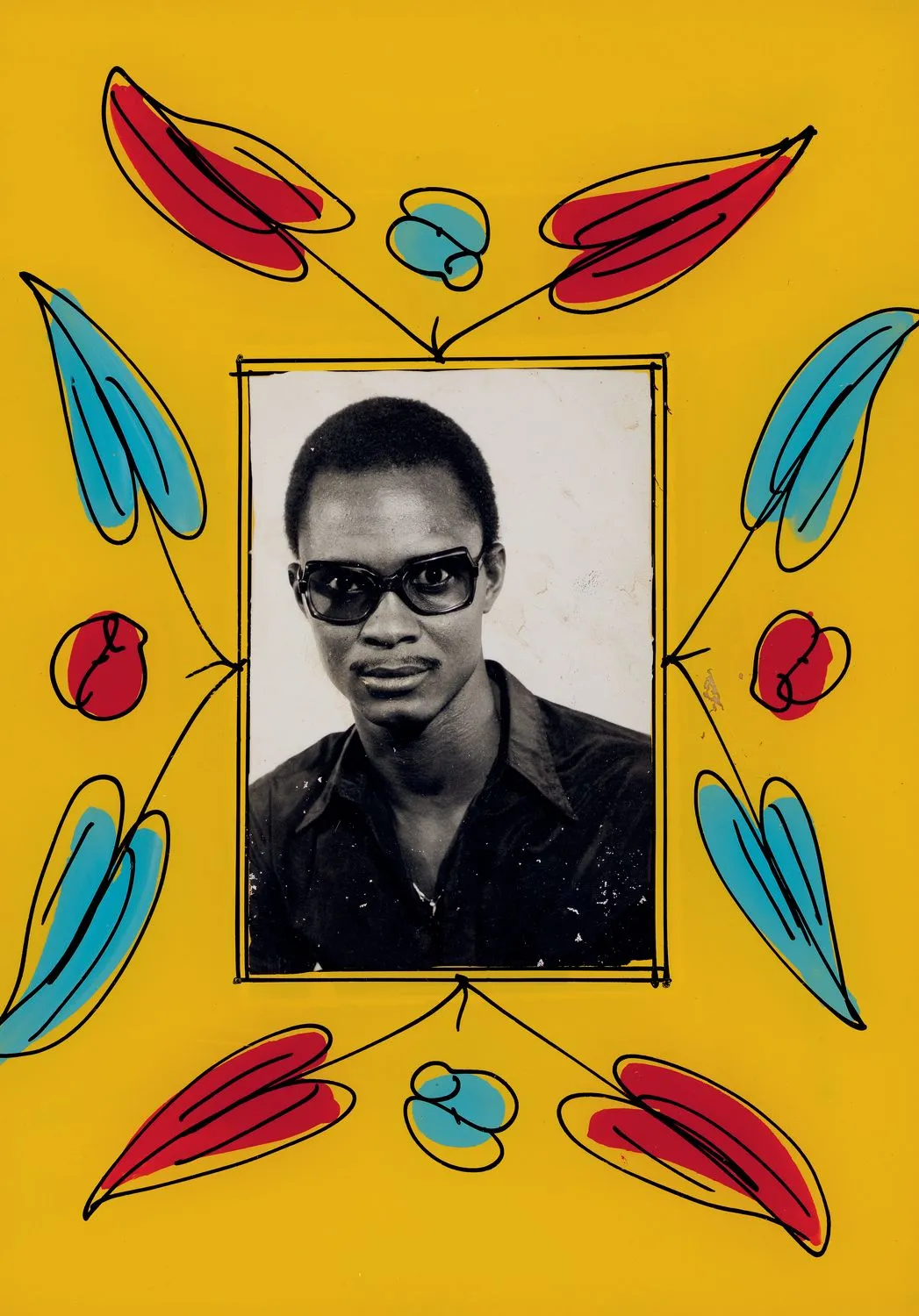

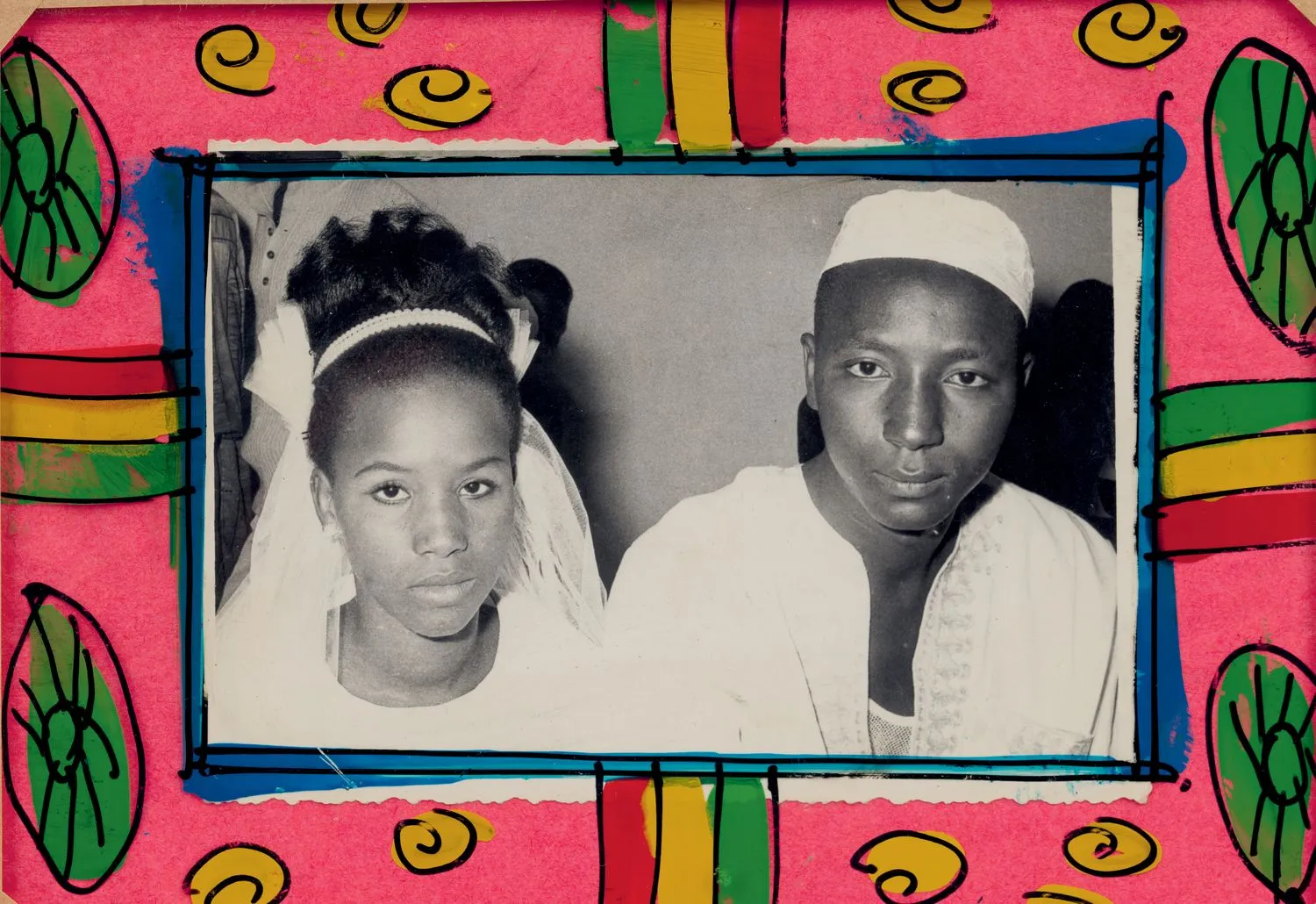

In a small, vibrant studio in Bamako, Malick Sidibé chronicled a generation redefining itself. Known as the "Eye of Bamako," Sidibé captured the exuberance of post-independence Mali with a singular intimacy. Now, Painted Frames, a new photobook recently published by Loose Joints, reimagines his work by pairing it with vivid hand-painted glass frames that revive the photographs' social life and emotional resonance.

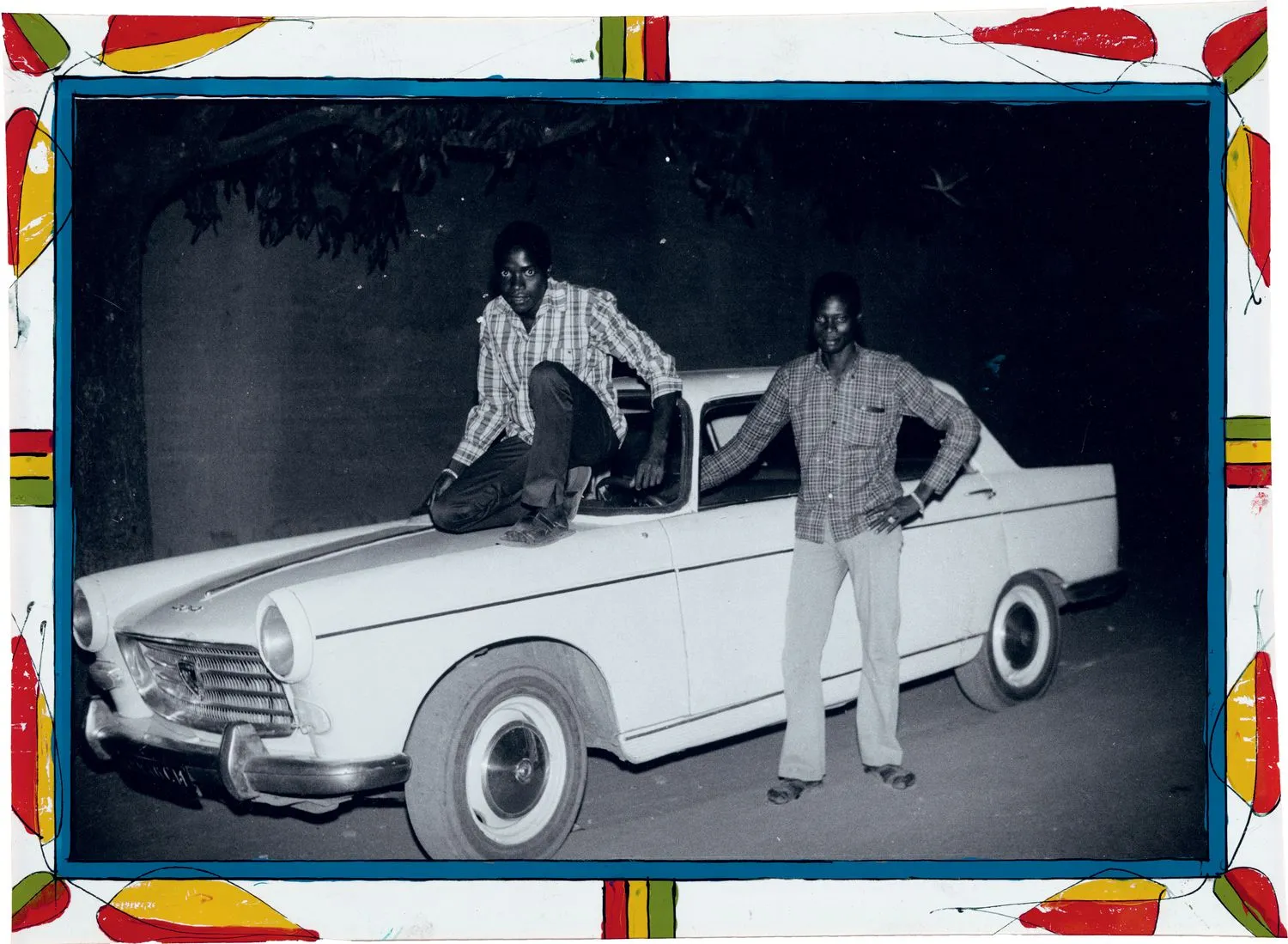

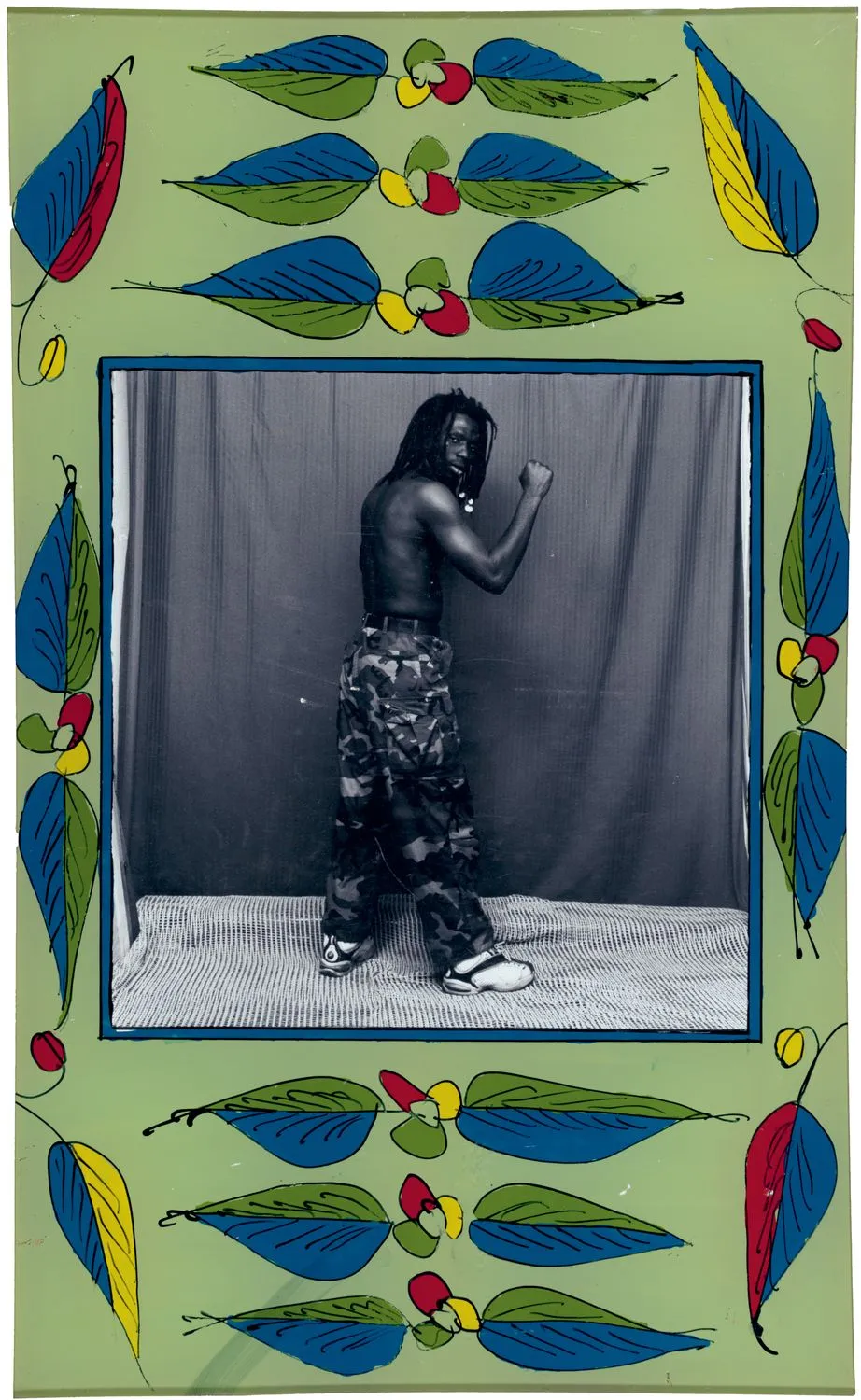

Sidibé's camera lingered on young men in sharply tailored suits, women in polka-dot dresses laughing against patterned studio backdrops, couples swaying at Christmas Eve dance parties, and friends reclining on the banks of the Niger River. His portraits radiated pride, aspiration, and a distinct sense of personal style. Studio Malick became a stage where sitters posed with props like radios, bicycles, or guitars, crafting images of modernity and joy that rippled far beyond Bamako's borders.

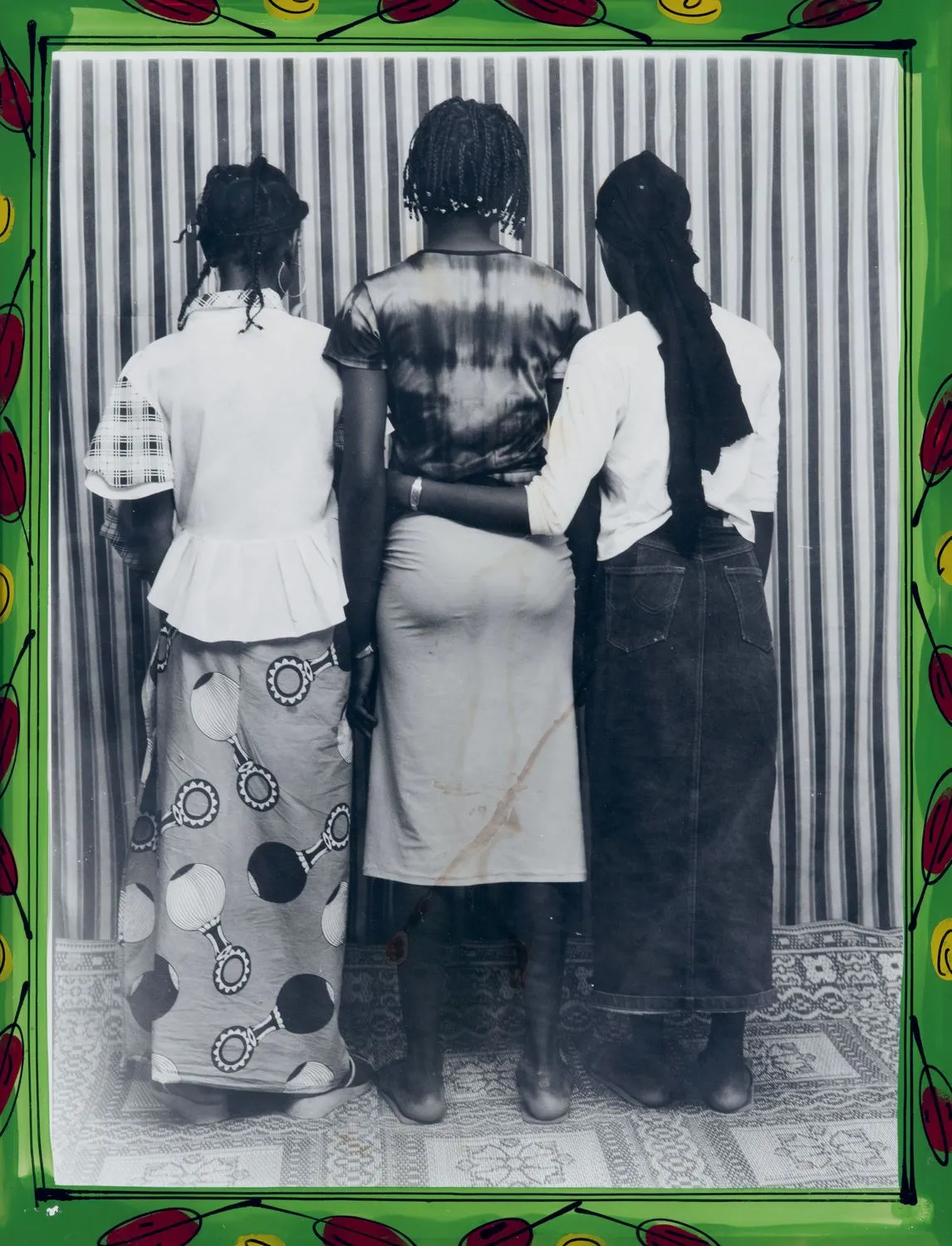

Painted Frames revives these photographs as living, breathing social objects. Collaborating with local artists such as Checkna Touré, Sidibé framed his images in brightly colored glass borders decorated with delicate foliage, swirling lines, and floral motifs. Each frame was crafted using the traditional West African reverse-glass painting technique. It acts as a second skin for the photograph: bold, intricate, and imbued with craftsmanship and care. Sidibé's subjects, youthful, stylish and rebellious, embodied a new African modernity fueled by soul music, Black Power politics, and diasporic dreams. His camera did more than record this spirit. It helped shape it, capturing the contagious electricity of a generation in motion.

The photobook also highlights Sidibé's role not just as photographer, but as curator of his own legacy. Toward the end of his life, he carefully selected images from across decades, landmark works such as Nuit de Noël (Happy Club) (1963) and later experiments such as Vues de Dos (2004), and housed them in new frames. This act of retrospective curation reveals that Sidibé was deeply conscious of the enduring weight of his archive.

Crucially, the project resists the Western art market's tendency to strip African photography of its original meaning. In Painted Frames, the worn surfaces, fingerprints, creases, and personal inscriptions are preserved, testifying to the photographs' journeys across families, borders, and generations. They are not exoticized artifacts, but living testaments to a generation's dreams and migrations.

Today, looking at these framed scenes—a young boy standing confidently, dressed in a sharply tailored suit, a young couple swaying mid-dance—feels like stepping into a world still vibrating with possibility. Through Painted Frames, Sidibé's vision shines anew: vibrant, rooted, and defiantly alive.