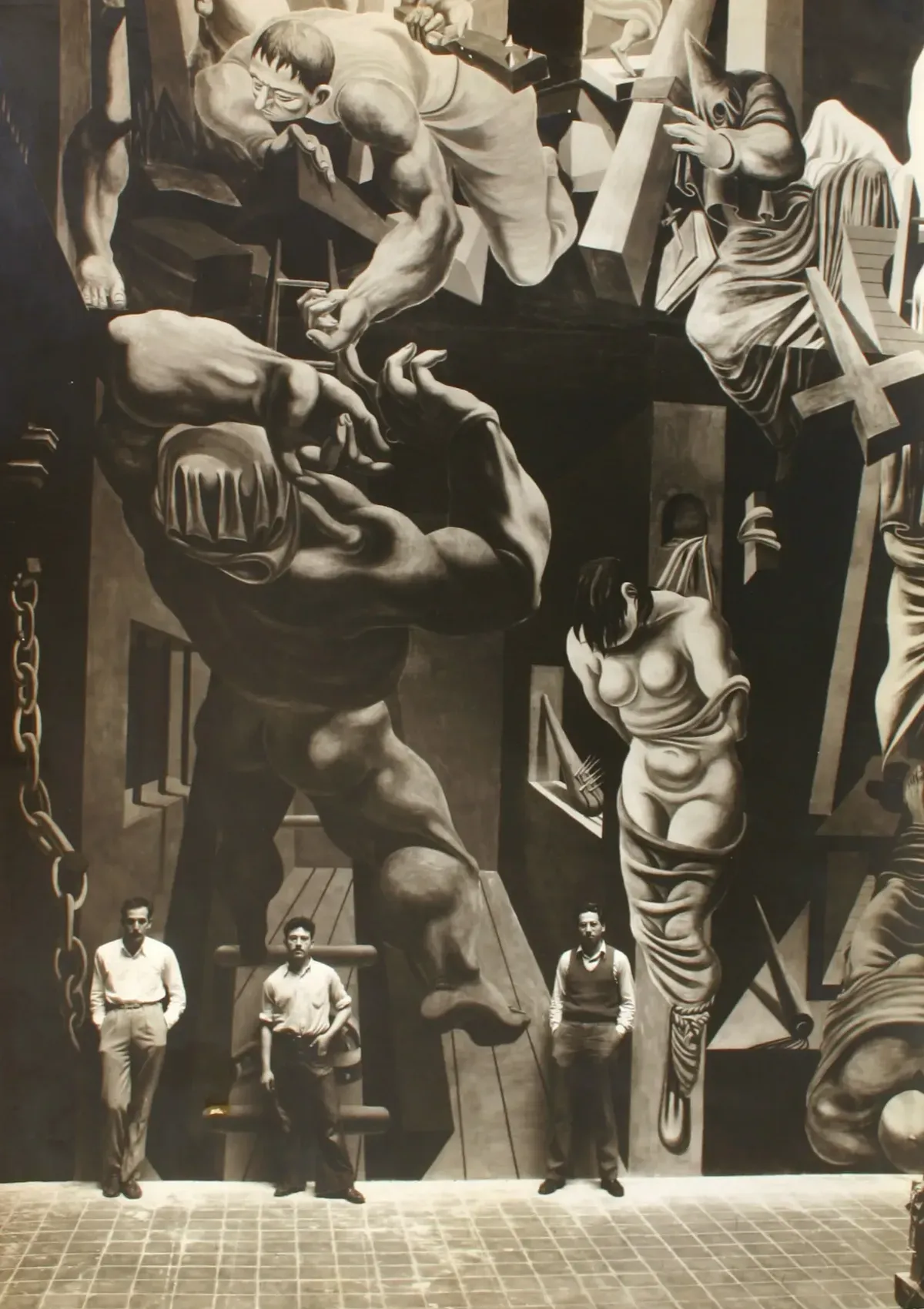

Reuben Kadish, Jules Langsner and Philip Guston with Gustavo Corona (above) in front of The Struggle Against Terrorism. The Philip Guston Foundation

Reuben Kadish, Jules Langsner and Philip Guston with Gustavo Corona (above) in front of The Struggle Against Terrorism. The Philip Guston Foundation Philip Guston and Reuben Kadish's The Struggle Against Terrorism (1934–35) is a searing indictment of oppression and brutality. Conceived during a period of mounting global fascism, the work presents a nightmarish vision of persecution and resistance, resonating as strongly today as it did nearly 90 years ago. Created at the invitation of David Alfaro Siqueiros, this immense fresco spans over 1,000 square feet in a Baroque palace in Morelia, Mexico, now the Regional Museum of Michoacán. Guston and Kadish, both just 21 at the time, wove a harrowing panorama of violence, drawing from history, religious iconography, and contemporary terror to warn against the rise of tyranny.

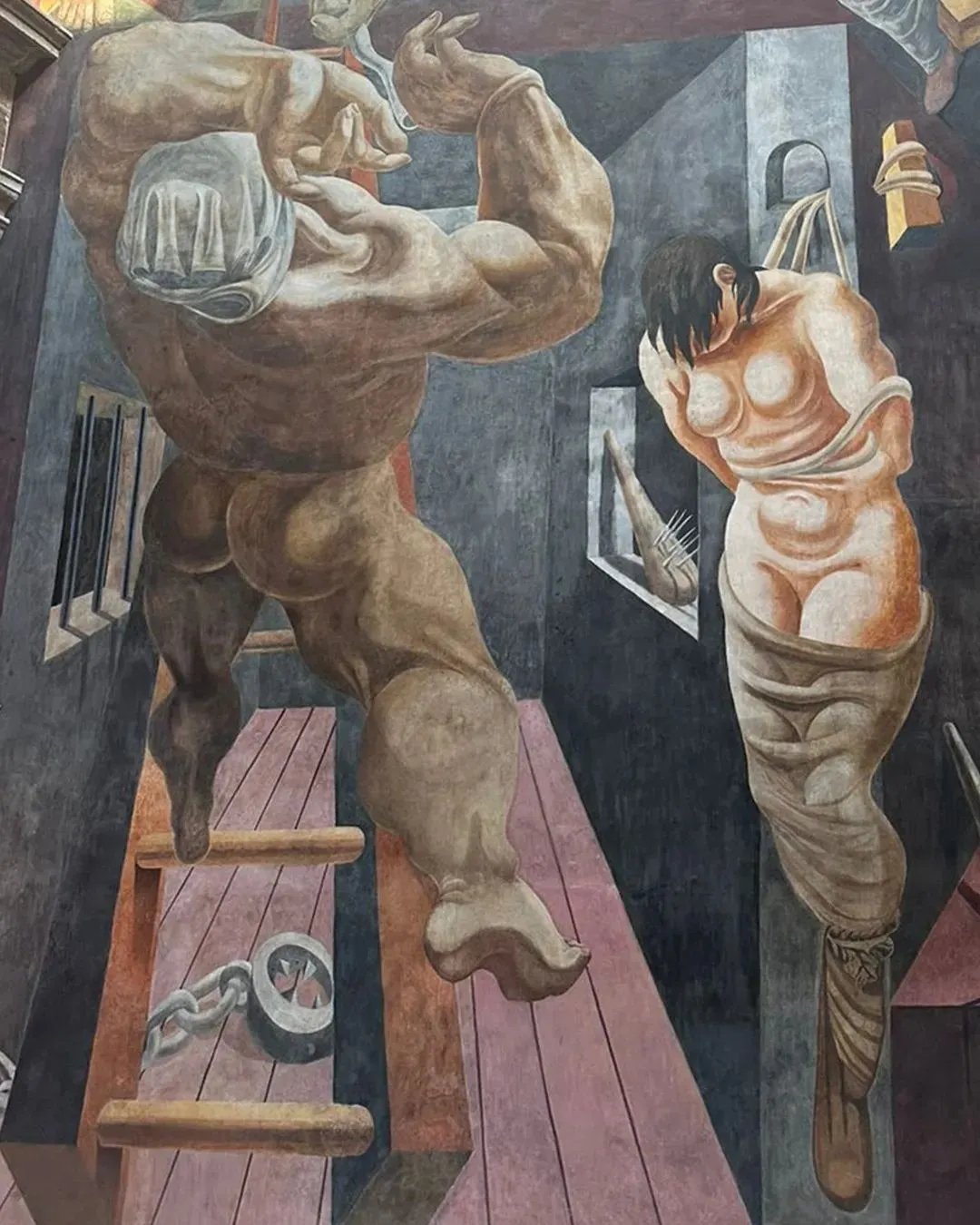

Hidden behind a false wall for decades and later damaged by climate conditions, the mural was now meticulously restored in collaboration with The Guston Foundation, Mexico's Ministry of Culture, and expert conservators. Led by the National Institute of Fine Arts and Literature, the restoration not only stabilized the fresco but revived its vivid colors and forms, preserving both its powerful visual narrative and the message that remains urgent in an era of resurgent far-right politics.

In the early 1930s, as fascist movements gained momentum across Europe and the U.S., Guston and Kadish were drawn to Mexico, where muralism had become a powerful political tool. Both had grown up amid the economic hardships of the Great Depression and witnessed the rise of white supremacist violence in the U.S., particularly the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan. As Jewish-American artists with leftist sympathies, they were acutely aware of the mounting threats of authoritarianism and racial terror.

Encouraged by their mentor, David Alfaro Siqueiros, they traveled to Morelia with poet and critic Jules Langsner, eager to contribute to the region's radical artistic landscape. With limited resources but a deep sense of urgency, they spent six months painting The Struggle Against Terrorism—creating a sweeping allegory of oppression and resistance.

Striking in its stylistic ambition, the mural pulls from an array of influences—Renaissance frescoes, Surrealism, and the dynamic compositions of Siqueiros—to construct a gripping and fragmented narrative of human suffering and struggle. Figures are stretched and contorted across the two-story surface, each scene portraying violence across history, from biblical persecution to the modern horrors of totalitarianism.

Guston and Kadish embraced Siqueiros' theory of polyangularity, a technique designed to produce multiple vanishing points, immersing viewers in the swirling, chaotic energy of the composition. The mural's scale demands engagement—one cannot passively observe it; instead, the eye is drawn from one gruesome spectacle to the next. Symbols of the Ku Klux Klan, Nazi insignias, and medieval instruments of torture coexist in an unsettling and relentless sequence.

The Struggle Against Terrorism already reveals Guston's preoccupation with themes that would define his career. Known for his later figurative paintings confronting racism and violence in America, he was grappling with these concerns decades earlier. The Klan figures he would revisit find their origins here, interwoven with historical atrocities and contemporary anxieties. In this way, the mural serves as a prototype for his lifelong interrogation of power and brutality.

For decades, the mural was largely forgotten—first hidden in the 1940s, then left to decay. Its rediscovery in the 1970s, followed by gradual recognition of its significance, mirrors the broader reassessment of Guston's career, which has gained renewed urgency in recent years. Now, with its meticulous restoration, The Struggle Against Terrorism reclaims its rightful place as a crucial chapter in the history of political muralism. It remains a raw, unsettling, and necessary work—one that reminds us of the cyclical nature of violence and the artist's role in bearing witness.

As Musa Mayer, Guston's daughter, aptly states, "Its message is as relevant today as it was 90 years ago." With radical right-wing movements on the rise, the brutal vision Guston and Kadish laid bare in 1935 is not just a relic of the past—it is a warning that remains as urgent as ever.