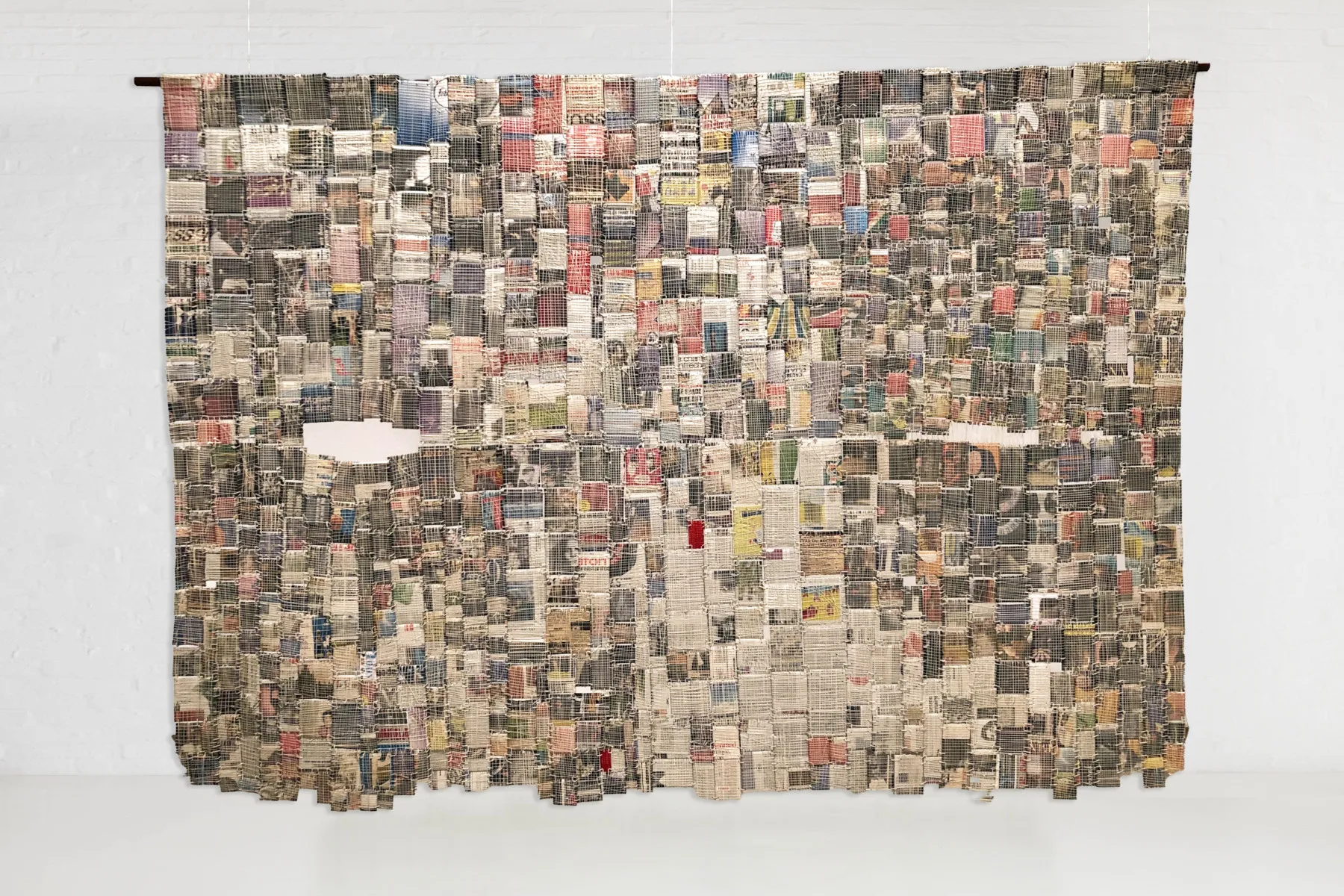

Moffat Takadiwa, Bhiro ne Bepa (Pen and Paper), 2023. © Dan Vezentan & Nicodim

Moffat Takadiwa, Bhiro ne Bepa (Pen and Paper), 2023. © Dan Vezentan & Nicodim In times of structural disintegration and social upheaval, objects bear silent testimony to personal and collective histories, revealing truths that defy simple representation. This impulse anchors signifying the impossible song, a group exhibition at Southern Guild Los Angeles curated by Lindsey Raymond and Jana Terblanche.

Bringing together 17 artists across diverse media, the exhibition embraces a plurality of voices, experiences, and visual languages, exploring the complexities of memory, material culture, and personal and collective histories. Through sculpture, photography, textiles, and found objects, the artists reveal how materials embody both knowledge and hidden histories, reflecting forces like defiance, displacement, and disintegration. The show examines the unraveling of political systems, as artists expose their fragility.

Raymond describes the curatorial mission as "interrogating the implausibility of resolute representation—of self, community, and nation," calling for global perspectives that are Pan-Africanist, self-aware, expansive, and queer.

Signifying the impossible song looks to how identity is formed both personally and inter-personally as well as by socio-politics, economics, geography, history, and other external forces and systems beyond our control. We wanted to highlight just some of the many worlds the artists extract from in order to return to self.

Terblanche adds that their intuitive, research-driven approach allowed them to listen to discordant voices and weave together personal histories. "We were not looking for a singular answer but embraced the conflict between individual and collective desire," she explains, finding meaning in contradictions rather than cohesion.

The exhibition’s title comes from Carl Adamshick’s poem Our Flag, which speaks to an unfinished reality. Raymond and Terblanche use this poetic inquiry to frame artworks grappling with the incompleteness of history and the limitations of representation. This tension between the material and the immaterial, the real and the imagined, forms the core of the show, positioning signifying the impossible song as an ongoing meditation on how objects and stories bear witness to time, memory, and change.

Ange Dakouo’s Édifice, a tapestry made from compressed cardboard and newspaper, evokes the spiritual potency of Dozo hunters’ amulets, preserving indigenous knowledge systems related to nature and spirituality. Meanwhile, Turiya Magadlela’s Mpilo Tutu I stretches pantyhose across a blood-red canvas, transforming this symbol of femininity into an expression of generational trauma, particularly in the context of South Africa’s femicide crisis. These materials carry pain, suffering, and resilience.

As Terblanche notes, some artists' choices might seem subtle, yet they carry profound significance within a specific curatorial framework. For instance, Lulama Wolf’s work subtly incorporates sand into her paintings, imbuing them with the essence of her homeland. The near-invisible texture speaks to the political significance of land in South Africa, connecting her art to broader issues of ownership and racial inequality. These pieces expand our understanding of materiality, showing how even the simplest elements can be charged with profound cultural and political significance.

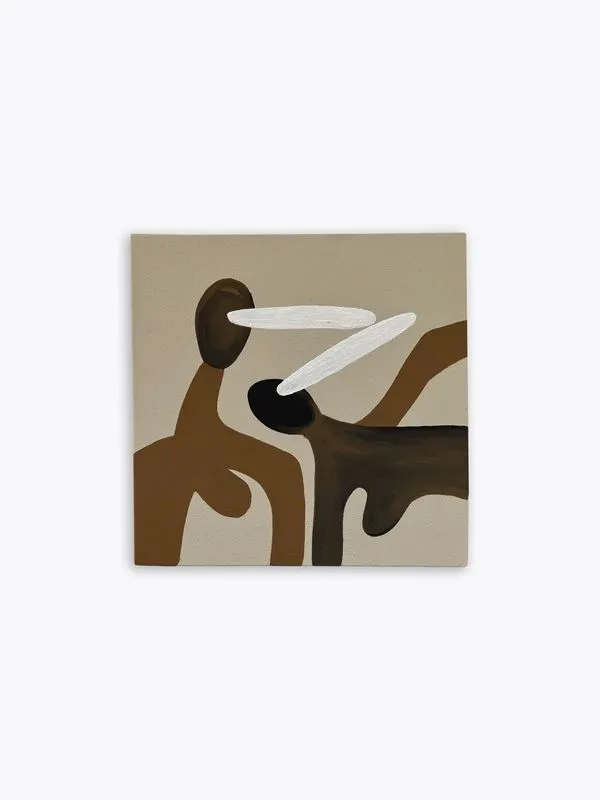

On the other hand, Sanford Biggers reimagines historical symbols in his Chimera and Codex series by blending Classical sculptures, African masks, and American quilts. This approach questions how meaning is constructed through history, disrupting familiar narratives. Bonolo Kavula focuses on shweshwe cloth, a material tied to her family’s heritage. Her tapestries, made from tiny cloth discs, reflect repeated acts of care and preservation, embedding cultural memories into abstract forms.

Reflecting the spirit of resistance against societal and historical forces, the exhibition allows the artists to reclaim narratives and assert their presence in spaces where they may have previously been marginalized. As Terblanche notes, "resistance is at the core of societal change, and we can always count on artists to find new ways to disrupt the status quo."

Roméo Mivekannin’s Bouguereau (The Myth of Orestes) critiques the absence of Black narratives in Western art history. In this large-scale painting, he superimposes his face onto William Bouguereau’s 1862 neoclassical work, jolting viewers out of their disbelief. This defiant act of self-insertion highlights the erasure of Black histories and calls for a revision of accepted narratives.

Zanele Muholi’s self-portrait Fika I, Highpoint I, London, part of their Somnyama Ngonyama series, reflects similar themes of invisibility and hyper-visibility as a Black woman and non-binary body. The artist boldly inserts themselves into spaces historically denied to them, often with humor and sensuality. In this work, they resemble a Frank Gehry building, with architectural forms enveloping their body. "The work speaks not only to socio-political inequality but to the creative and cultural exclusion within architecture," Terblanche explains, "the economic inequality implicit in city planning; forced removals, displacement and other structurally designed forms of racism and classism."

The exhibition draws on the powerful interplay between personal narratives and broader cultural or historical themes, weaving together intimate experiences with collective memory. The artists challenge notions of identity and belonging while offering nuanced perspectives on complex social realities.

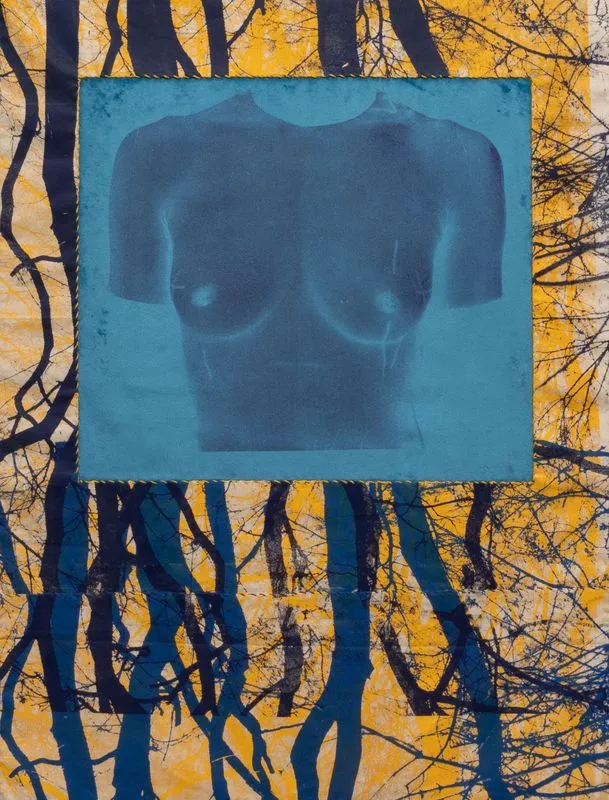

For instance, Zohra Opoku’s All the magic, all the words said against me… merges the personal and political within the exhibition’s themes. The work features before-and-after images of Opoku’s body during radiation treatment, alongside photos of wintry trees in a Berlin park, all screen-printed onto velvet and cotton in a collaged style. The title, taken from the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, reflects on mortality, while the trees symbolize the everyday nature of life, death, and the indiscriminate nature of illness.

"My hope is that viewers feel and experience deeply personal works such as Opoku’s and make the link that cancer, like power and greed, is a spreading and volatile force – a universal evil which is therefore binding," Raymond notes. "Opoku’s memoir archive speaks to the instinct for survival and resilience; to rise against malignant forces."

The curators reflected on the tension between individual and collective aspirations, particularly in how these dynamics are expressed through material culture. They acknowledged the challenge of representing the collective through a singular visual language, recognizing that such an approach inevitably excludes certain groups and individuals. "I’m left with an overwhelming feeling that an all-inclusive truth does not serve the greater good," Terblanche explains. "There is strength in bringing dissonant voices together to celebrate the nuances of being human."

By weaving together diverse perspectives, signifying the impossible song challenges viewers to confront the complexities of identity, history, and the human condition. The exhibition foregrounds material culture as a medium for expressing deeply personal and political stories, emphasizing how these individual narratives intersect with broader socio-political contexts. Ultimately, it asks whether we can imagine a future where our individual histories coexist without exclusion, offering a radical vision of defiance and unity.

The exhibition signifying the impossible song will be on view at Southern Guild in Los Angeles until November 14th, 2024.