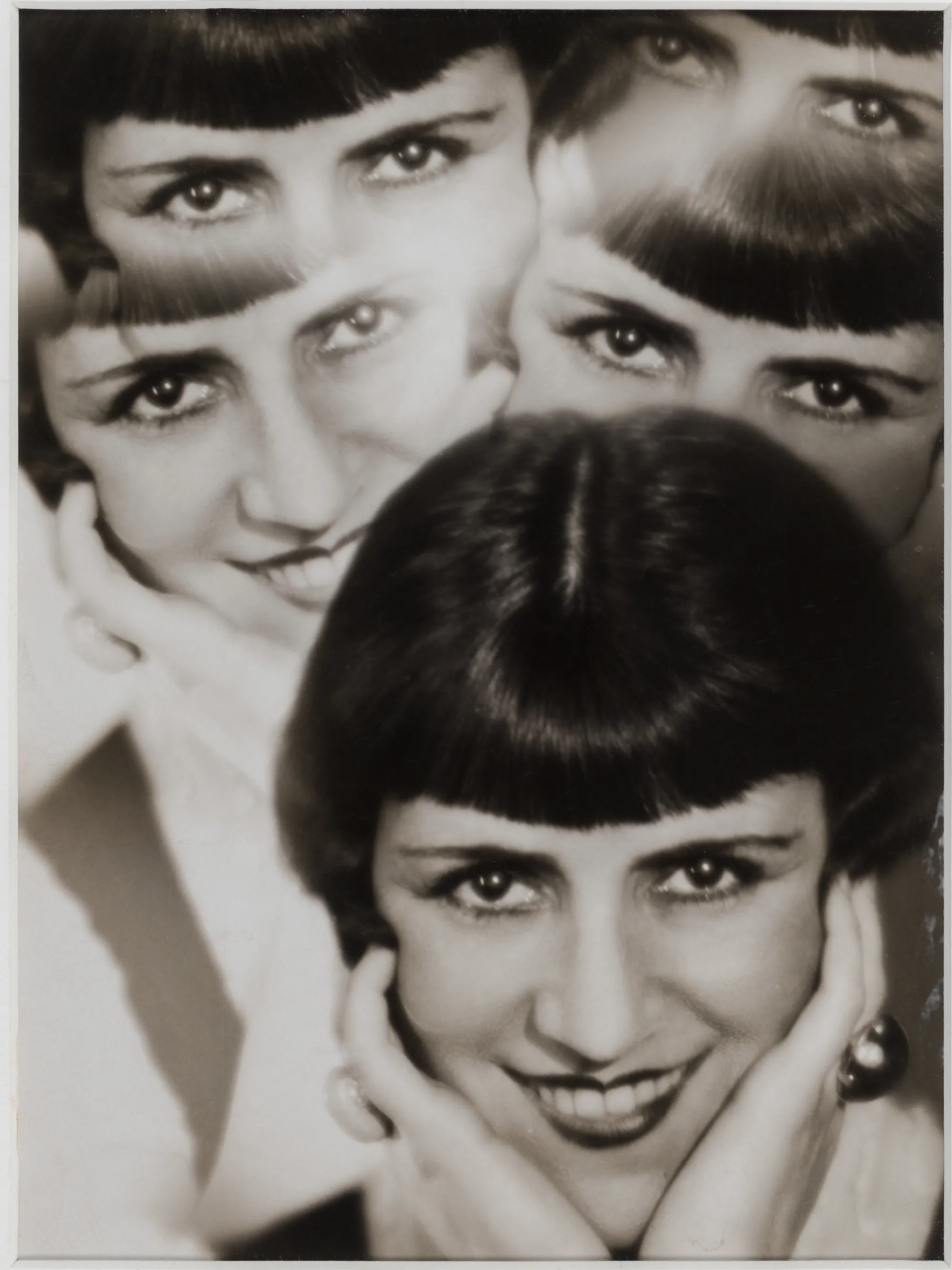

Dora Maar (Henriette Theodora Markovitch) (French, 1907–1997), Portrait of Nusch Eluard, c. 1935. Gelatin silver print, 5 x 7 inches, Collection of David Raymond & Kim Manocherian, © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Dora Maar (Henriette Theodora Markovitch) (French, 1907–1997), Portrait of Nusch Eluard, c. 1935. Gelatin silver print, 5 x 7 inches, Collection of David Raymond & Kim Manocherian, © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris In an intriguing turn of events, photography evolved from a tool for capturing reality into a medium for revealing hidden aspects of the soul and human consciousness. For this transformation to occur, the setting had to be pruned to its essentials—a post-war society, skinned to its most basic urges and needs, where violence and desire reigned freely. And another important ingredient not to be missed: the imaginative spirit of the avant-garde artist.

This shift leading to the development of a particular style and movement known as Surrealist photography occurred following the First World War and soon spread from Europe across the globe.

Emerging alongside Surrealism—the avant-garde movement that put automatism, the unconscious, dreams, and the human psyche at the centre of its investigations—Surrealist photography pushed the expressive possibilities of the medium, producing captivating and intriguing images featuring unusual details, unexpected arrangements of objects, and an eerie, dreamlike atmosphere.

The founder of Surrealism, André Breton, had already in 1921 recognised the transformative power of photography for reshaping artistic expression. He wrote:

“The invention of photography dealt a blow to old modes of expression, both in painting and in poetry, where the automatic writing that appeared at the end of the nineteenth century is a true photograph of thought.”

The transformative impact of Surrealism on photography is currently explored in the exhibition The Subversive Eye: Surrealist and Experimental Photography from the David Raymond Collection at the Dalí Museum, showcasing over 100 works by 50 artists spanning the period from 1925 to 1948.

After World War I, artists faced a changed reality, marred by the tragedies and insanity of war violence. In response, they sought escape through critical art that radically questioned all aspects of society, interrogating also the notions of normality and sanity.

While Dadaists rejected aestheticism and social conventions in pursuit of anti-art, Surrealists, led by Breton and artists Joan Miró, Jean Arp, Max Ernst, René Magritte, and Salvador Dalí, declared the total abandonment of reason in favour of exploring the unconscious. Inspired by the teachings of Sigmund Freud, they dived into the realm of fantasy, employing different approaches and techniques to present their visions while maintaining formal excellence.

Concerned with automatism and the removal of art from imitative traditions, Breton set a new precedent in art history with his 1924 Surrealist Manifesto, in which he established the principles of the new artistic movement. Against realism, which he loathed “for it is made up of mediocrity, hate, and dull conceit” and logic, which he dismissed as “applicable only to solving problems of secondary interest,” he positioned Surrealism, a “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought.”

Rather than adopting the anti-institutional stance that characterised other avant-garde movements, Surrealism sought to expand artistic norms and did not reject the institution of art per se. However, the surrealist experimental approach disrupted many artistic dogmas and introduced a novel visual language based on chance, unusual combinations, and experimentation.

This freedom of expression was most readily embraced in photography. With Surrealist photography, different experimental techniques and image-making strategies emerged, which strongly influenced art in the following decades as well.

The new impetus for experimentation came on the heels of technological advances. The invention of more portable Rolleiflex and Leica cameras and 'faster' lenses providing more control over angles and sharpness as well as more spontaneity in operation paved the way for highly experimental approaches.

At the beginning of 1921, Man Ray (1890–1976) developed a specific approach to capturing objects by setting them on sheets of photographic paper and exposing them to light. These Rayograms, as he would call them, later featured in László Moholy-Nagy’s Bauhaus publication Malerei, Photographie, Film, and gained international fame.

In collaboration with Lee Miller (1907–77), Ray also developed the process of solarization, where photographic paper was additionally exposed to light during the developing process, creating dreamlike results. This technique became widely popular in the 1930s and was adopted by other photographers like Osamu Shiihara (1905–1974) and Erwin Blumenfeld (1897–1969).

As Breton emphasized, photography could best respond to "the goal they had hitherto set for themselves… to break with the imitation of appearances."

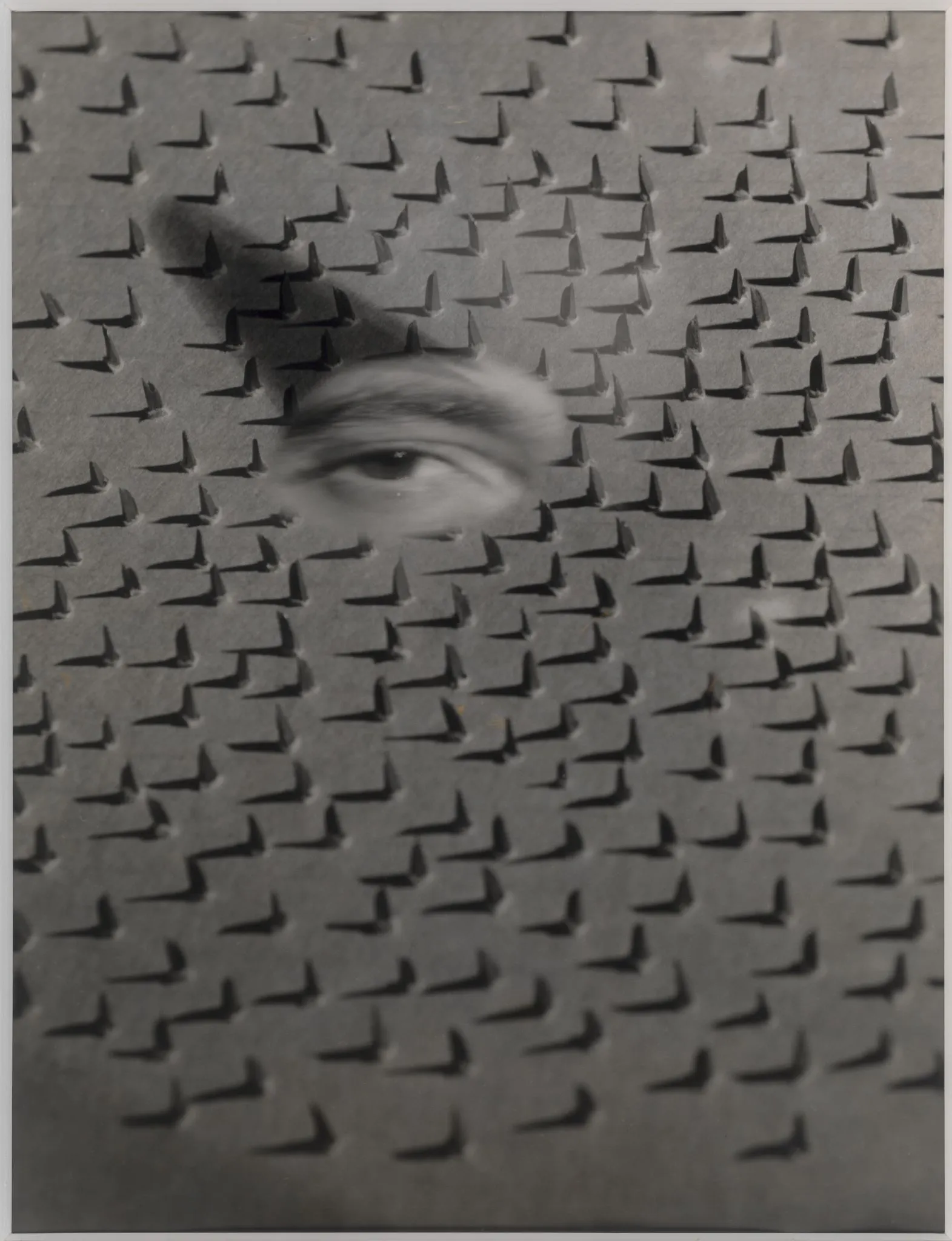

Besides developing new techniques, Surrealist photographers also experimented with different points of view and exposures, framing, and sharpness. The images were often combined, with collage and photomontage becoming dominant techniques for manipulating reality. Made of photographic images but often including print images as well, collages corresponded, in their formal aspects, to Dada poems, which randomly recombined phrases and words. Dora Maar (1907–1997) created disturbing and unreal representations by using cut-out elements from other photos, while Franz Roh (1890–1965) made collages out of print media.

Writing about his painterly practice in 1935, one of the leading Surrealists, Salvador Dalí, described his paintings as "color photography done by hand," revealing, in one sentence, the significance of the medium for the new movement.

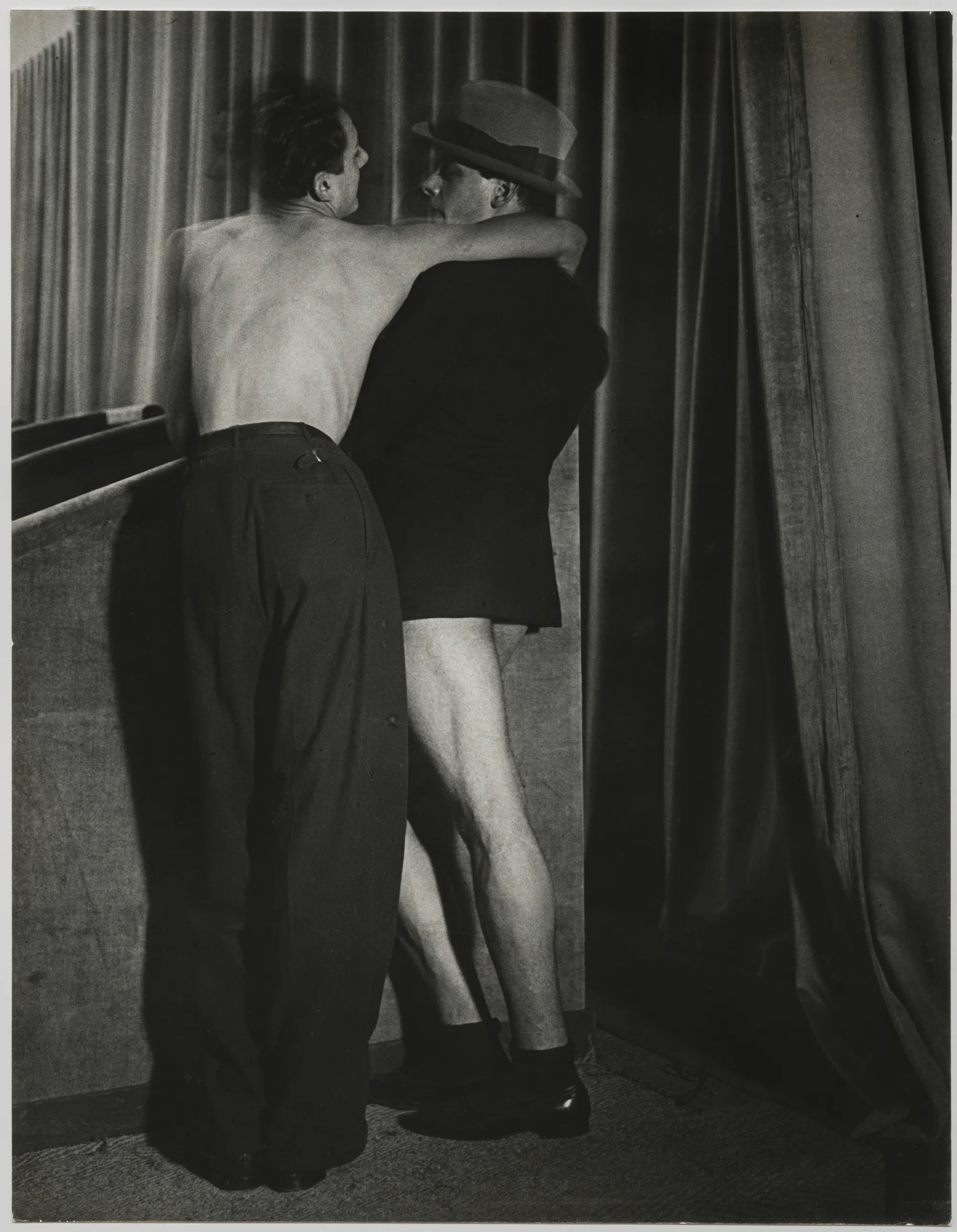

While challenging technical limitations, Surrealist photographers also devotedly explored the limits of perception, introducing perspectives from beyond the conscious.

"They privileged the abandoned, errant, disfigured, or achingly beautiful above the ordinary. They saw in the photograph's inhuman gaze a tool of liberation. The camera reveals what our mental order does not allow us to see. The photograph proves, as Dalí remarked, the truth of Surrealism—that there is a world parallel to this one," explains Hank Hine, Director of Dalí Museum.

Dreams and desire were sister subjects for Surrealists, and one of the recurring topics linked to both was the image of a woman. Man Ray, Brassaï (1899–1984), and Joseph Breitenbach (1896–1984) often represented an idealized figure. Paul Éluard's wife, Nusch Éluard, was considered the ideal surrealist woman and featured in many surrealist works.

As art critic Wiliam Jeffett notes in the exhibition catalogue, besides the woman's figure, the interest of surrealist photographers also gravitated towards odd combinations of objects, as seen in Ray's and Maar's works. Maar started her explorations with images featuring plant leaves, which she gave an abstract quality, while Roger Parry (1905–1977) reminisced on the future in his close-ups of hands holding a crystal ball.

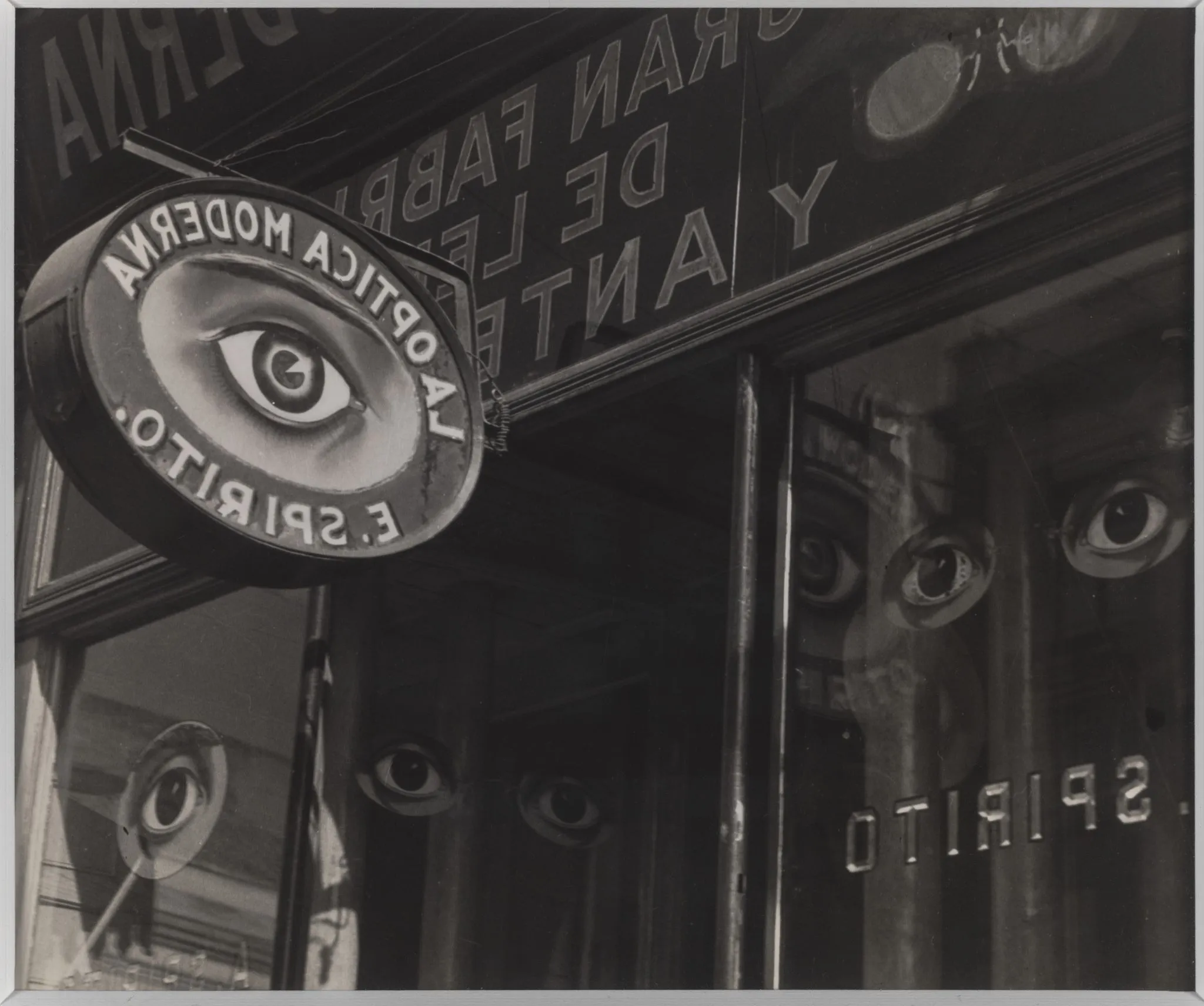

Mexican photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo (1902–2002), experimented with objects and shadows in revealing different mental visions, although he rejected the Surrealist label. Avant-garde photographers of Czechoslovakia, such as Josef Bartuška (1898–1963) and Ladislav Emil Berka (1907–1993), crafted ghost-like images, and the similar mysterious and often ominous atmosphere was present in the works of Maurice Tabard (1897–1984). His photos taken at Gare Montparnasse train station introduced another important topic in Surrealist photography—the mystery of the everyday and of urban surroundings.

Particularly alluring were mannequins and dolls from shop windows and modern amusements such as circuses and carnivals. Mannequins became an international subject, as "the realism of the mannequin seems to have worked with and against photographic realism to introduce a disruption of ordinary reality," explains Jeffett. This obsession also hews to considerations of identity and the self, another important aspect of surrealist explorations.

“Photography at the service of Surrealism, more than any other art form, including painting, was arguably the perfect vehicle for exploring the fragmentation of the self so central to the surrealist project.”

Although preoccupied with the unconscious, Surrealists also remained acutely aware of the reality that surrounded them and deployed their cameras for political and social concerns. A good example of such an approach are desolate photographs of old Paris by Eugène Atget (1857–1927), who rejected being called a Surrealist, with many others following in his steps. Maar also partook in these themes with her portraits of people on the street.

The collection of Surrealist photography at The Subversive Eye exhibition—offering a rare opportunity to see a large number of these works in one place—is revelatory of its importance in decoupling art from its imitative function, allowing free rein to dreams, desires, and, quite often, fears that plague our modern society. The dreamlike imagery that challenged conventional perception and technical experimentation proved significant and inspirational for later art movements as well, including Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and contemporary art, where distortions of reality, automatism, identity, and the subconscious remain prevalent.

The exhibition The Subversive Eye: Surrealist and Experimental Photography from the David Raymond Collection will be on view at the Dalí Museum in Saint Petersburg, Florida, until May 4th, 2025.