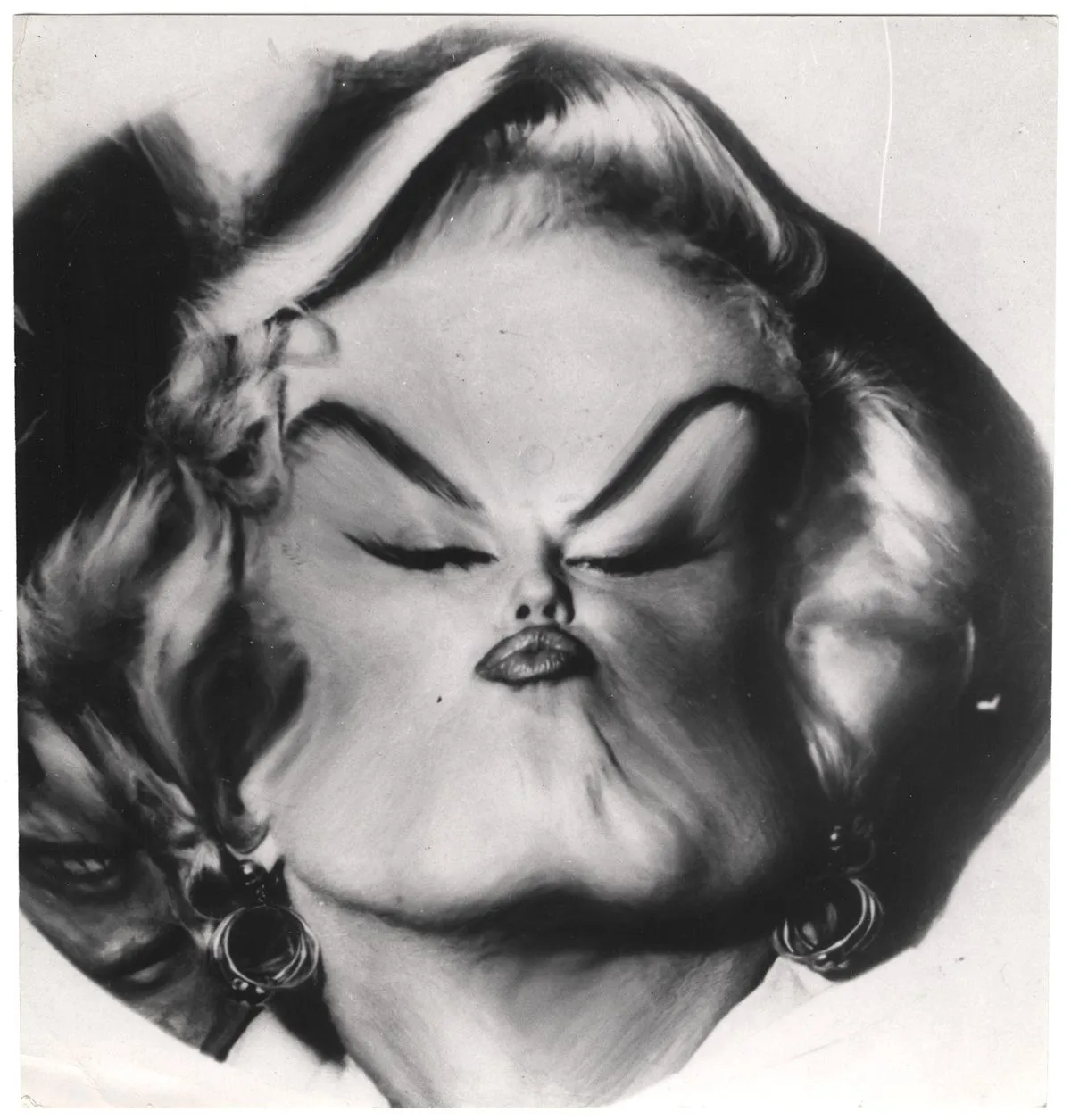

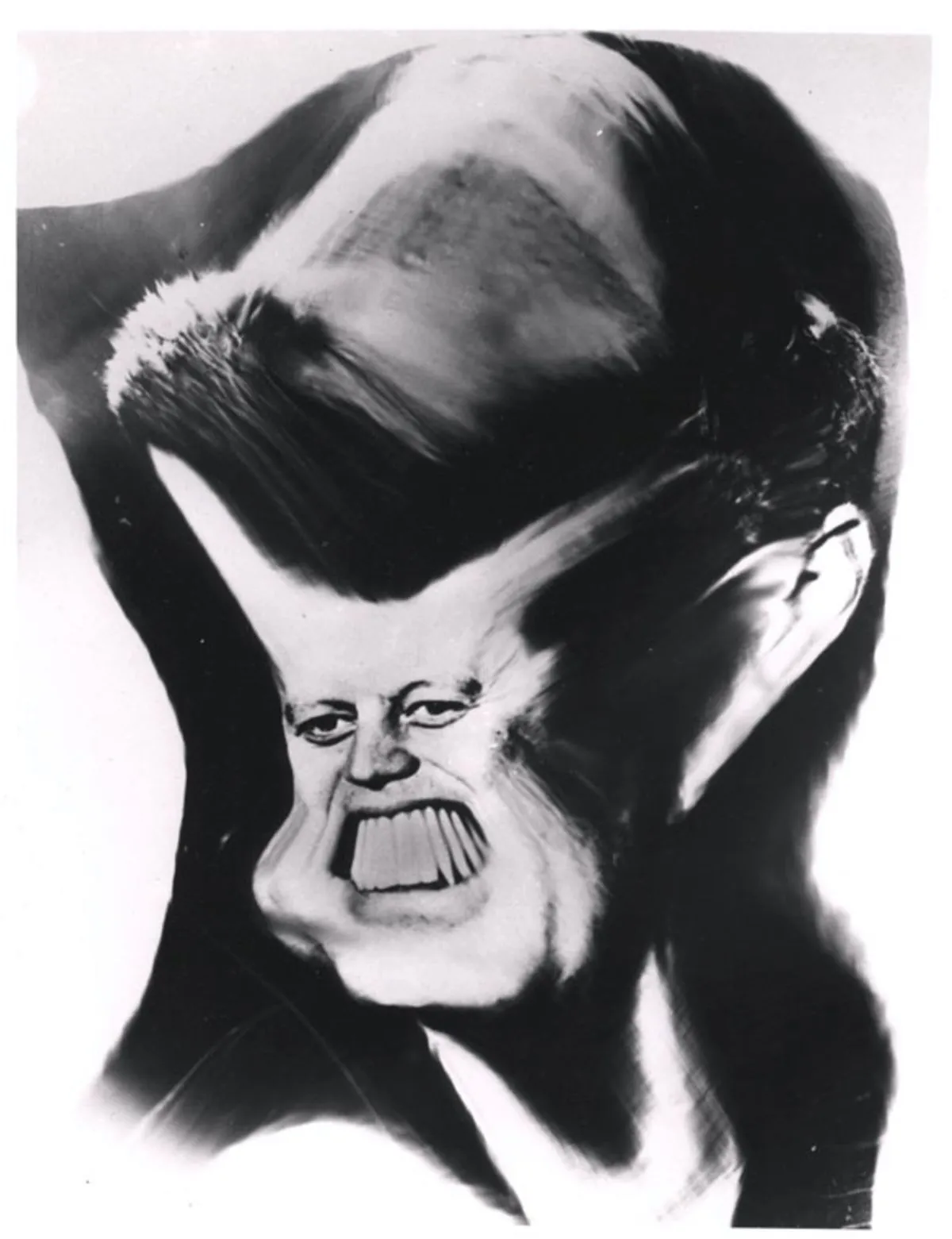

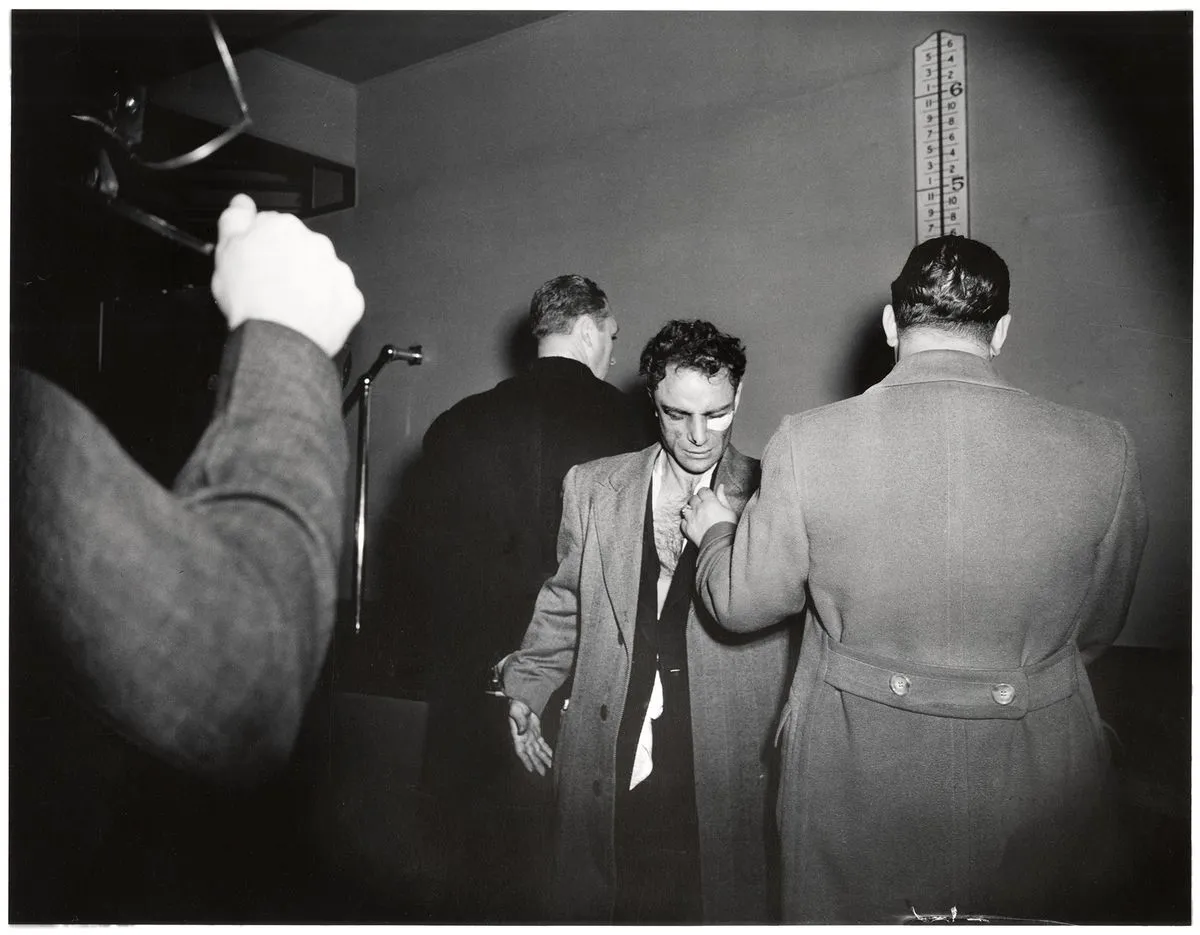

Weegee, St. Louis Gag Shot, ca. 1950, International Center of Photography. Bequest of Wilma

Wilcox, 1993 (20531.1993) © International Center of Photography/Getty Images

Weegee, St. Louis Gag Shot, ca. 1950, International Center of Photography. Bequest of Wilma

Wilcox, 1993 (20531.1993) © International Center of Photography/Getty Images Throughout history, myths have surrounded great artists, adding intrigue to their personalities, creative processes, or ways of life. Whether discrepancies in biography, haunting secrets, or unresolved enigmas, such myths pull us toward certain oeuvres like moths to flame—even though we may never truly unravel the figures behind them.

One such figure is the great American photographer Arthur Fellig, better known as Weegee, who pioneered a method and genre of photojournalism, ushering in a new era of street photography. Primarily acclaimed as a freelance press photographer in New York City during the 1930s and 1940s, Weegee was often rumored to be the first on the scene. The unique method of Weegee photography revolutionized street photography by capturing scenes of arrests, thefts, murders, and fires practically as they happened.

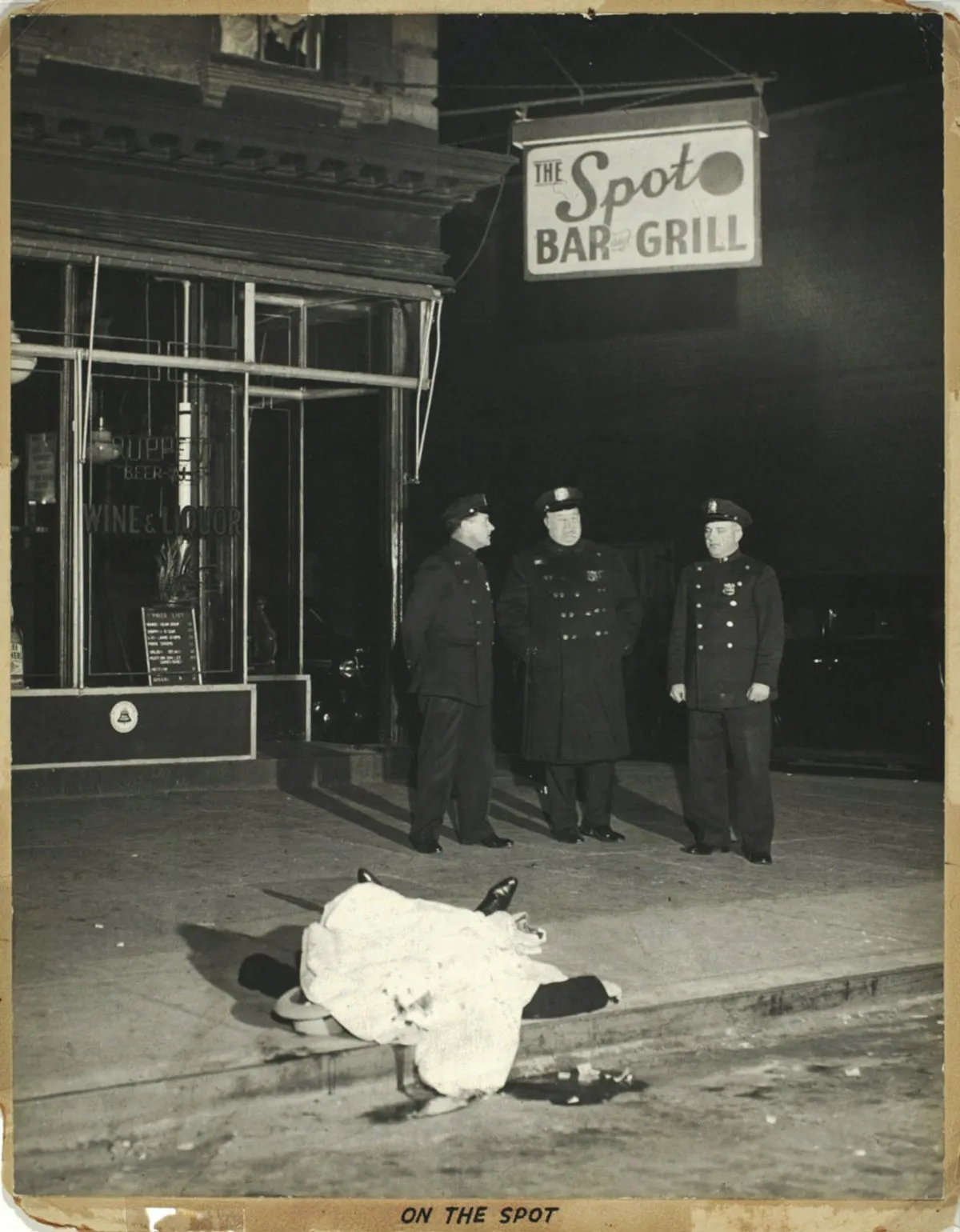

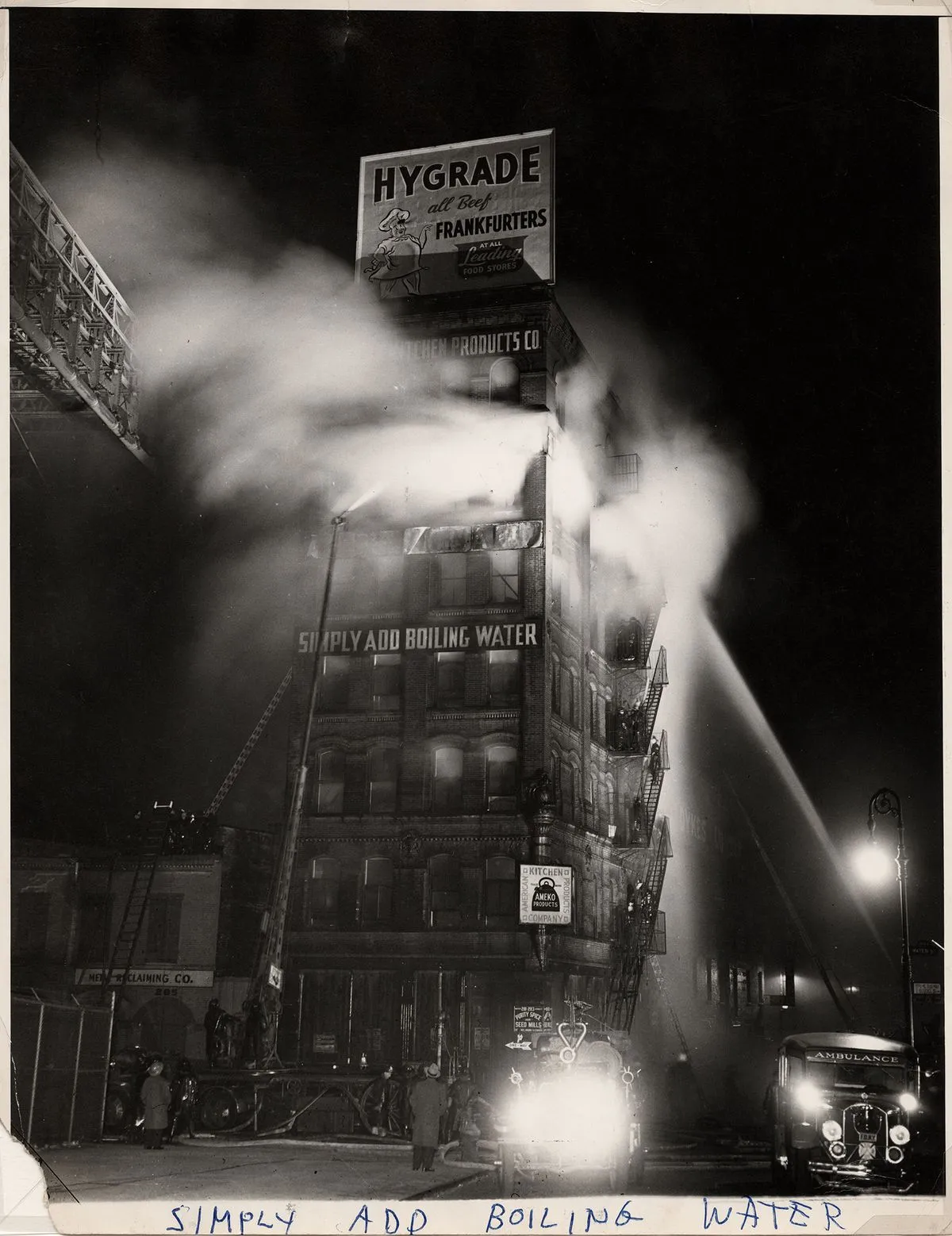

Fresh from the street, he would later sell the photographs to news magazines, including the Herald-Tribune, Daily News, Post, the Sun, and PM Weekly, to name just a few. Starkly contrasted and always taken with a flash; his photographs found the beauty within the horror. At the same time, the street photographer's immediacy and swiftness blazed a trail for revisioning photojournalism and introducing tabloid photography.

Now presented at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York after its debut at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris, the exhibition Weegee: Society of the Spectacle revisits the photographer's work through a thematic lens. Curated by Clément Chéroux, it examines how Weegee navigated and documented the line between tragedy and glamour, horror and desire.

Using ICP's complete Weegee archive—the world's most extensive holding of his studio work—the exhibition re‑examines his visual commentary on society by bridging his early New York street reportage with his later Hollywood caricatures. By foregrounding the persistent theme of spectacle—from crime scenes and fires to red‑carpet premieres—the exhibition reveals how Weegee's portrayal of the "society of spectators" spans both raw urban reality and the glossy allure of fame. As Chéroux notes, Weegee had an uncanny ability to "capture life's extremes, from high society to the underworld."

Often working at night, Weegee’s images of crime, fire and urban unrest reveal the harsh realities of 1930s and 1940s New York. His later shift to Hollywood did not distance him from this focus on spectacle but rather amplified his satirical approach, as he created playful distortions of celebrities that critiqued the American obsession with fame.

How Arthur Fellig Became Weegee

Born as Ascher Fellig on June 12th, 1899, in a Jewish family, Weegee migrated to New York at the age of ten, leaving his native Zolochiv, then a part of Austrian Galicia, modern-day Ukraine. The steamship passenger list records the photographer-to-be as "Usher," a name that was anglicized and eventually adjusted to Arthur upon his arrival. However, Arthur Fellig entered the pages of art history with his well-known nickname, Weegee, shrouded in mystery as to how it appeared and what it meant.

According to the most widely accepted theory, the name Weegee was a misspelled reference to the Ouija board, the fortune-telling device to which the photographer was often linked. In an effort to make sense of his uncanny ability to arrive at crime scenes before anyone else—unaware that he had a police radio in his car—many attributed his speed to a kind of mysterious foresight. Like someone consulting a Ouija board, Weegee seemed to predict events before they happened, a myth he welcomed, even if it hinged on a spelling error.

According to another theory, the name Weegee originated from his early days in press photography, when he worked as a "squeegee boy" at the New York Times. The nickname, initially meant to mock the menial task of wiping excess water from prints, became a badge of pride as he mastered the technical process of preparing photos for chrome-plated sheets. He ultimately adopted the name Weegee in the 1930s.

Weegee actively shaped the legends around him. His flamboyant look—cigar clenched, Speed Graphic at the ready—was a deliberate performance. In interviews and self‑published zines, he leaned into the Ouija myth, amplifying his aura of mystery. He embraced the persona of a clairvoyant, someone who could predict crime scenes before they happened. This mythical quality, combined with his "f/8 and be there" philosophy—which he later coined to summarize his approach to photography—set him apart from other photographers. By embodying this larger-than-life persona, Weegee ensured that he was not just another technician behind the lens but a character in the spectacle he captured.

With no formal education, Weegee plunged into the world of photography at a young age, quitting school at 14 to help support his family. Raised in the slums of the Lower East Side, he watched his father scrape by selling goods from a pushcart. Determined not to wait for opportunities to come to him, he took on various jobs—including photographing children on pony rides—setting the course for his career. He moved frequently between studios, eventually landing at ACME Newspictures, where he honed his craft as a darkroom technician.

In 1935, as New York was still reeling from the Great Depression, Weegee left the darkroom behind for the streets of New York. Newspapers were flooded with headlines about crime and violence, desperate for images to match the sensational stories. Sensing an opportunity, Weegee went to great lengths to capture the most striking and revealing photographs of the city's nighttime horrors. Initially relying on tips from hanging around the Manhattan police station, he took things further in 1938 by installing a police radio in his car—along with a portable darkroom—becoming the first American photographer allowed to do so. His innovative approach added to his growing legend.

Many accounts—perhaps in an effort to underscore his modest background—frame Weegee as a self-taught photographer who had never heard of Alfred Stieglitz, Ansel Adams, or even the Museum of Modern Art. Yet his work entered the art world relatively early, beginning with an exhibition at New York's Photo League in 1941. Soon after, MoMA began exhibiting his photographs, including in the 1944 Art in Progress show, where his work appeared alongside works by Stieglitz, Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy, Berenice Abbott, and others.

In 1945, Weegee published his first photobook, Naked City, a visual and narrative journey through New York's streets as seen through his eyes and lens. The title was later purchased by film producer Mark Hellinger, who adapted it into the 1948 film The Naked City, heavily inspired by Weegee's gritty aesthetic.

From the very start, Weegee wasn't simply chasing headlines—he was driven by responsibility to his family and a fierce need to prove himself in two worlds he never quite belonged to: the immigrant slums of the Lower East Side and the nascent art establishment. That tension between outsider and insider would fuel both his empathy for society's margins and his relentless work ethic.

Weegee's flash-flooded images of crime scenes, street life, and human drama did more than document—they dramatized. His mix of stark lighting and gritty subject matter reshaped photojournalism, producing images that felt as theatrical as they were real.

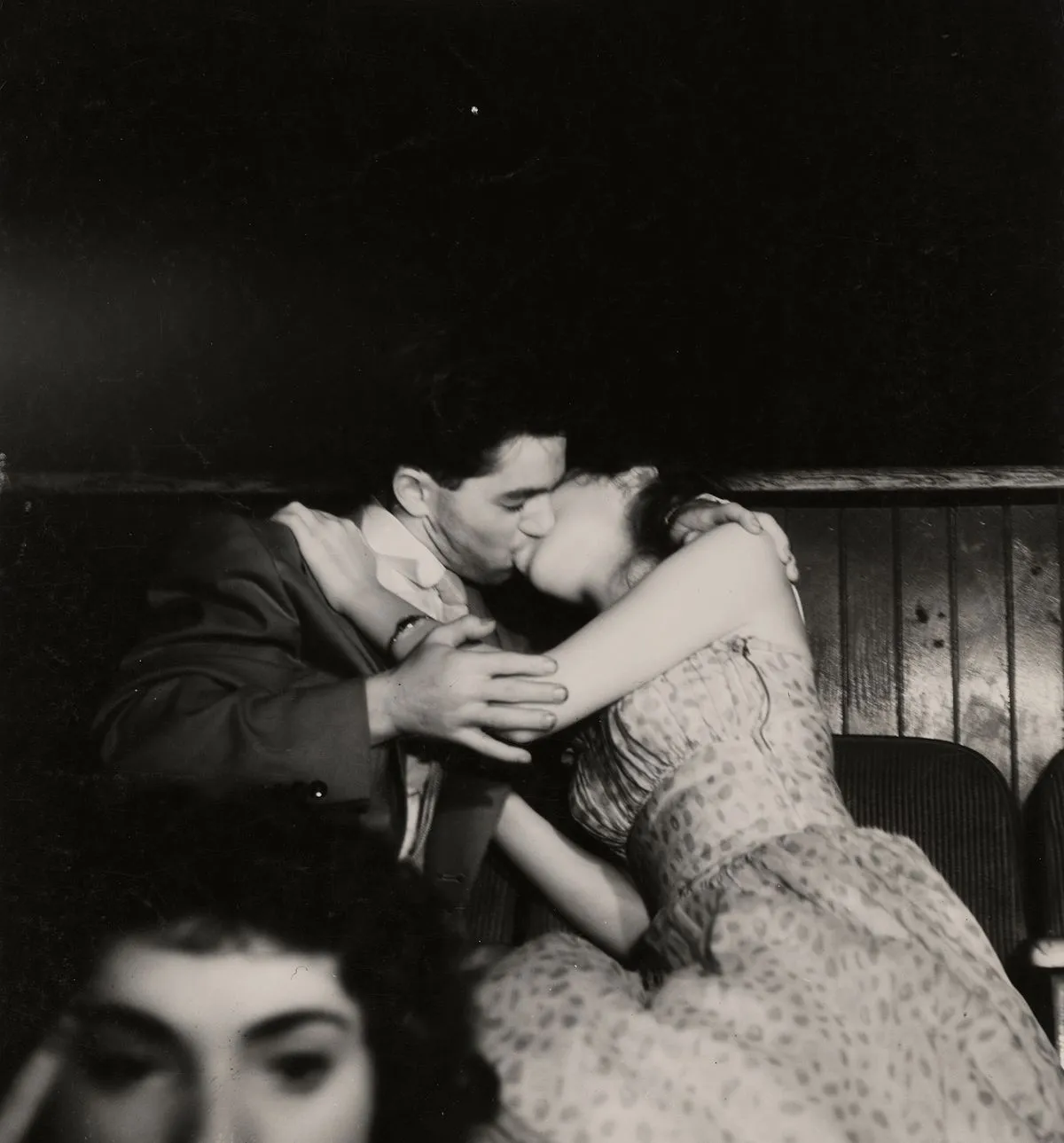

What set his work apart was its embrace of spectacle—not as empty sensationalism, but as a mediated reality, in the sense later theorized by Guy Debord: a reflection of society's fears, fantasies, and voyeuristic instincts. What made Weegee's images so arresting wasn't just what he photographed, but how. His confrontational style was urgent and emotionally raw. He wielded his flash like a spotlight, flattening scenes into high-contrast dramas that exposed every wrinkle, tear, and trace of violence. His proximity to tragedy—whether a murder victim, a grieving mother, or lovers caught mid-embrace—created a visceral immediacy rarely seen in journalism. The result was visual theatre, not quiet observation.

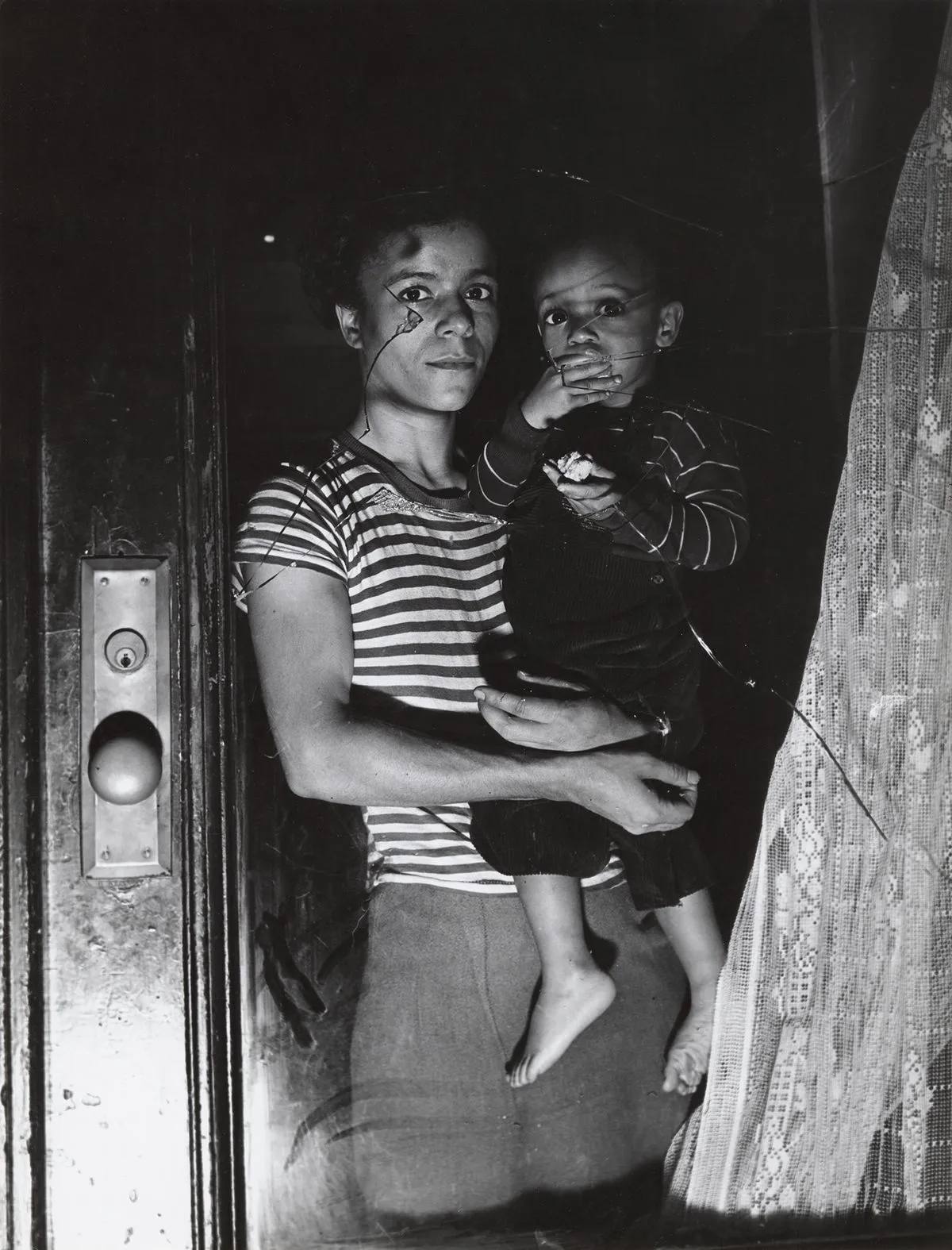

He got close—both physically and psychologically—often just feet from the bodies he captured: victims of fires, shootings, or street violence. His emotional tolerance for contradiction and distress gave his work its disarming power. Yet beneath the spectacle lies a haunting emotional core. I Cried When I Took This Picture, showing a mother and daughter in anguish as their family perishes in a tenement fire, is devastating not just for what it shows, but for what it refuses to turn away from.

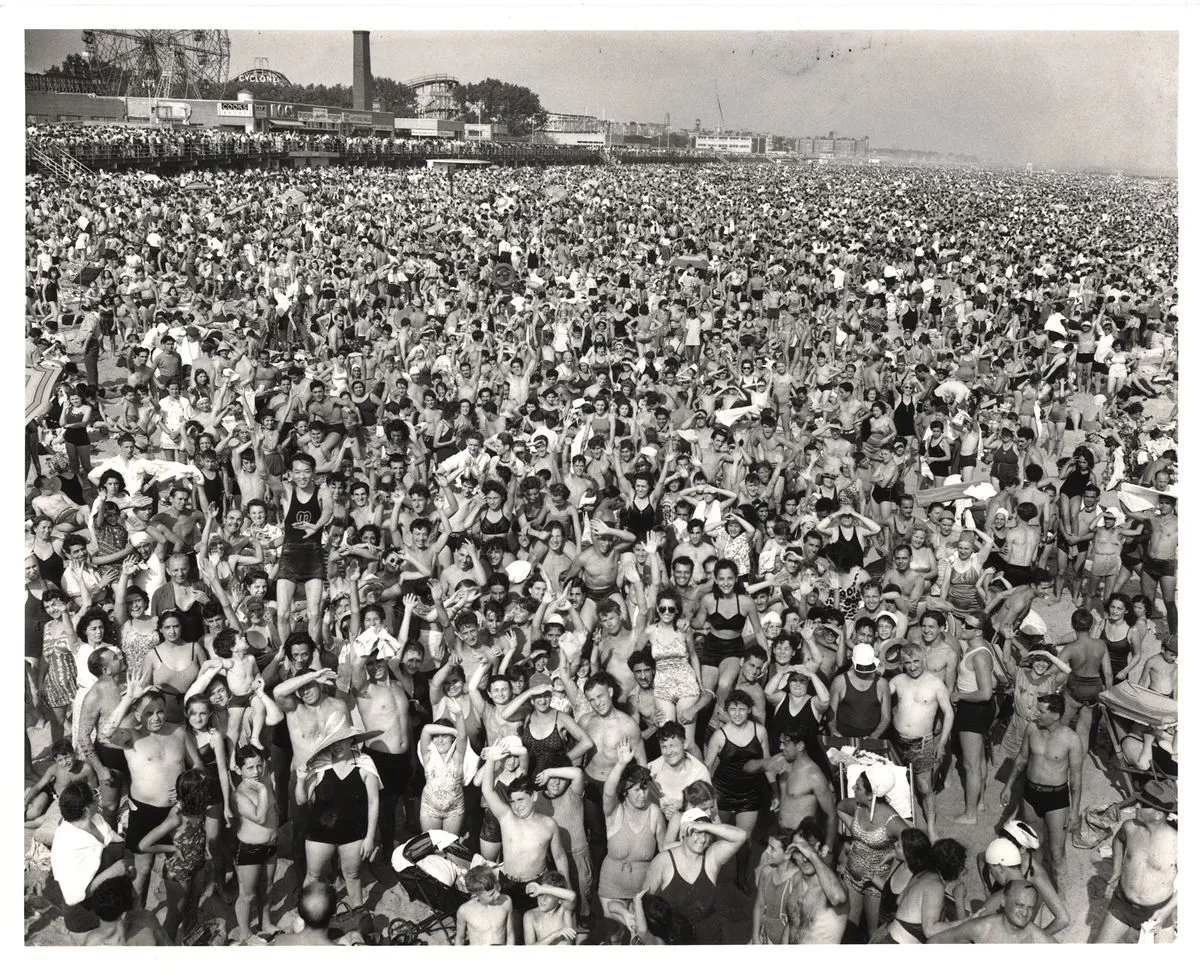

While many of his images blurred the line between truth and performance, others were staged to provoke. Some were candid: crowds at Coney Island, lovers in the park, regulars at Sammy's—"the poor man's Stork Club." But images like The Critic, in which a disheveled woman sneers at two opera-goers in fur, reflect deeper tensions around glamour and class. These moments point toward what Weegee would later call the "society of spectators"—a public complicit in the spectacle, always watching from the margins. Whether scandalous or mundane, he often turned his lens on the crowd itself, compiling a social portrait of the city through its outcasts, misfits, and circus performers. In this way, he became an American counterpart to Brassaï, capturing the charged nocturnal life of the metropolis.

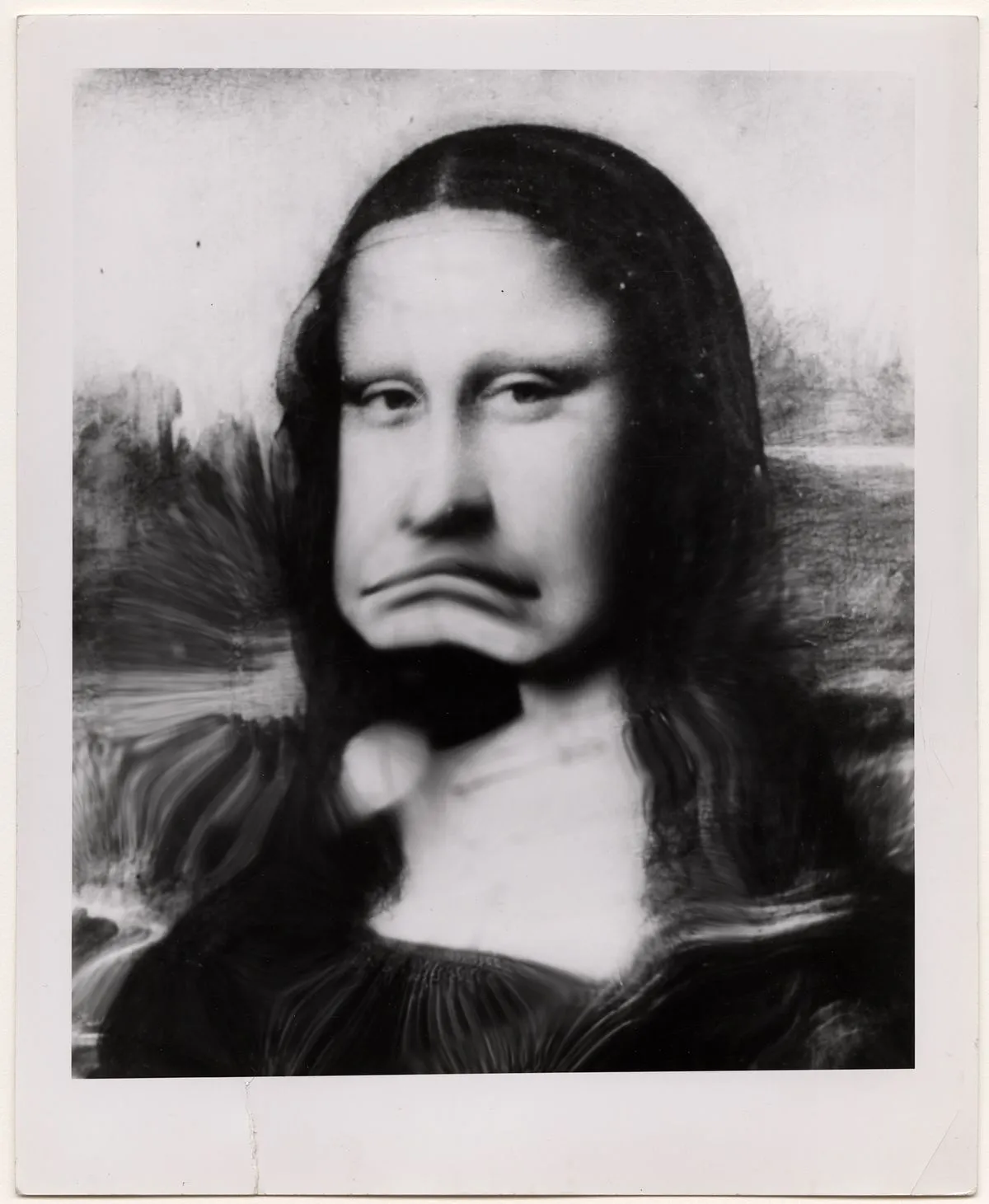

In later years, Weegee turned his camera on fame itself. His Hollywood Distortions series mocked celebrity culture by morphing familiar faces into grotesque caricatures. The same critical eye that once exposed the raw emotion of crime scenes now turned to the glossy shallowness of stardom. But the theme remained constant: the spectacle, in all its forms, reveals society’s deeper contradictions.

Elisabeth Sherman, Senior Curator and Director of Exhibitions and Collections at ICP, notes that while Weegee likely didn't anticipate the image-saturated world we now live in, his "provocative and prescient perspective on urban life forces us to reflect on how we now exist simultaneously as both consumers and the consumed."

In an age where technology and constant image sharing shape our reality, Weegee's work challenges us to reconsider the camera's role not only as a witness but as an active participant in the creation of spectacle.

The exhibition sharpens this focus through three recurring themes: The Spectacle of the News explores Weegee's iconic nighttime shots of crime scenes and fires, where gawkers and bystanders are as integral to the frame as the events themselves; The Society of Spectators centers on those on the margins—from glamorous parties to everyday street life—highlighting the dynamics of watching and being watched; and Hollywood Distortions examines his late satirical work, in which the faces of fame are warped into masks, skewering the absurdity of celebrity culture.

Weegee didn't just capture moments—he staged and performed them for the lens, drawing the viewer into the spectacle of looking. Poverty, grief, glamour, and absurdity often shared the same frame. Beneath the surface charge of the tabloid lies something sharper: a commentary on class, voyeurism, and the performance of urban life. The city wasn’t just his subject—it was his stage.

Weegee's legacy lies not only in the archive he left behind but in the visual logic he helped shape. His gritty immediacy and theatrical flair reshaped photojournalism, paving the way for photographers who blurred the boundaries between art, reportage, and social critique. The tension between authenticity and construction in his work ripples through the images of later photographers—from Diane Arbus's empathetic portraits to Garry Winogrand's raw urban scenes, and even the stylized realism of Magnum's narrative approach.

Shrouded in mystery and full of swagger, the persona Arthur Fellig created—the ever-ready photographer, cigar in mouth, bulb flash in hand—anticipated the rise of the artist as celebrity, a model later perfected by Pop Art icon Andy Warhol. In the age of livestreams and curated online identities, Weegee's work feels oddly prophetic. Long before the term media spectacle entered common use, he understood that news wasn’t just consumed—it was performed. His photographs mirror our voyeuristic gaze, collapsing the distance between witness and participant.

The exhibition Weegee. Autopsy of the Spectacle will be on view at the ICP in New York until May 5th, 2025.