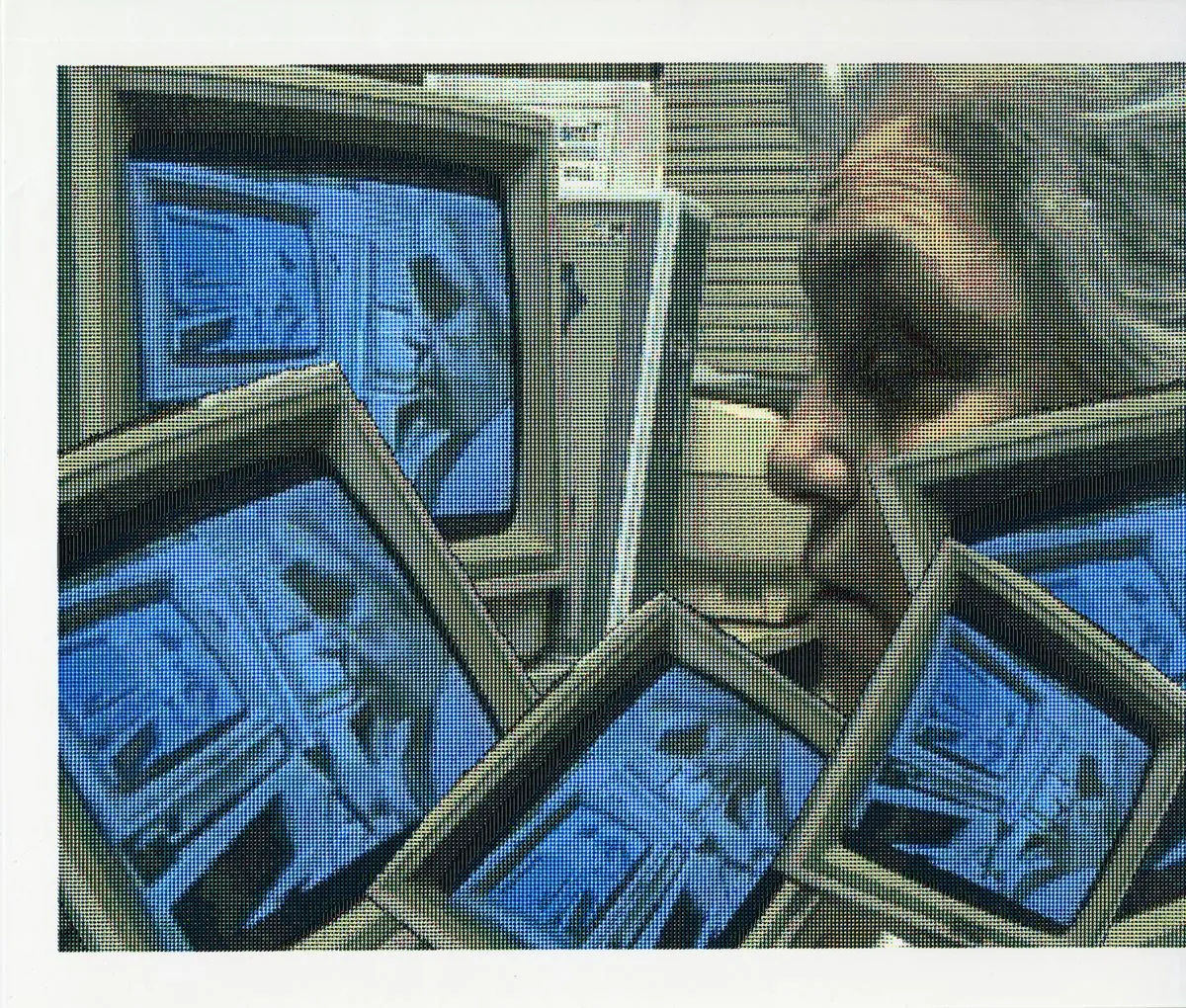

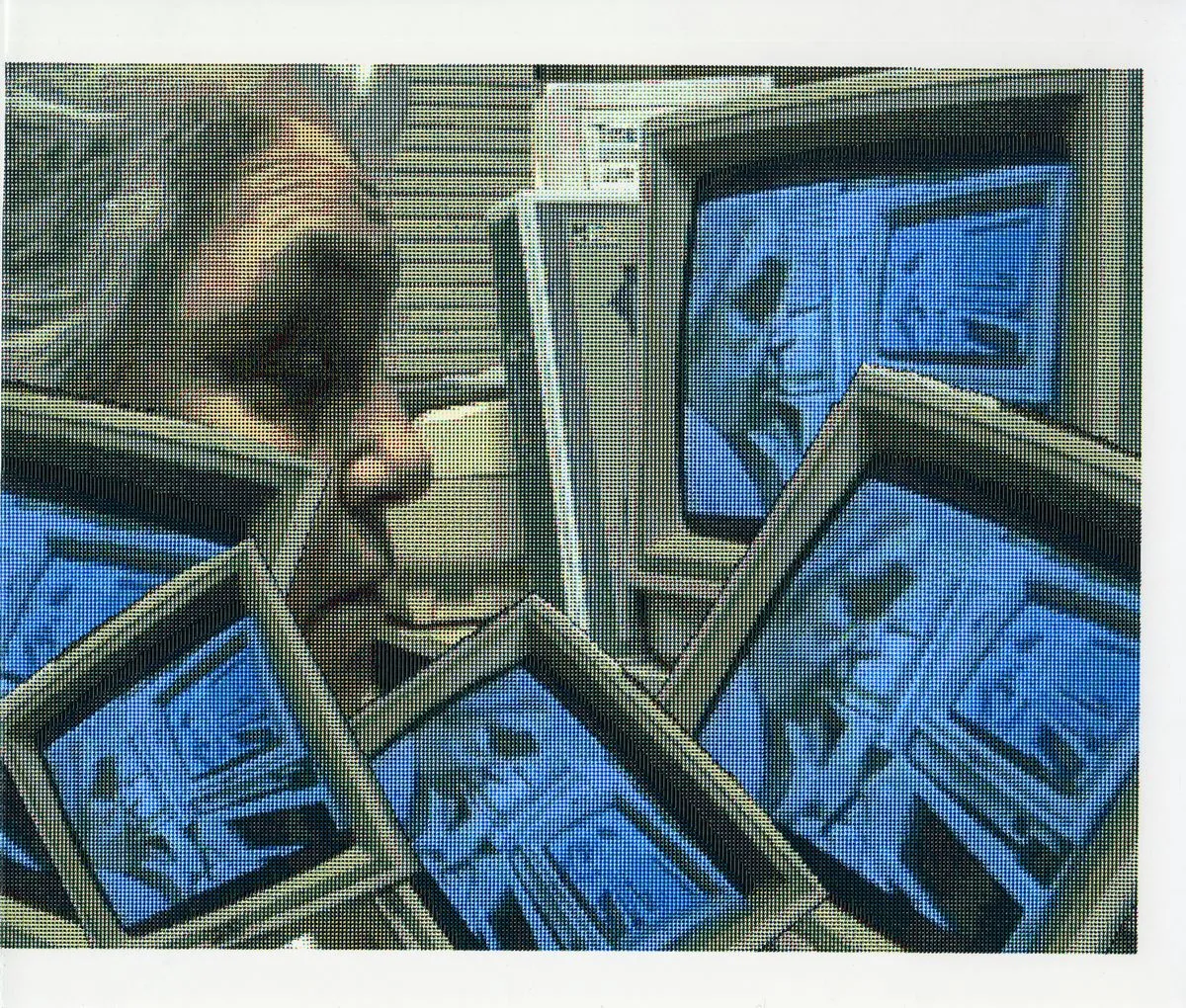

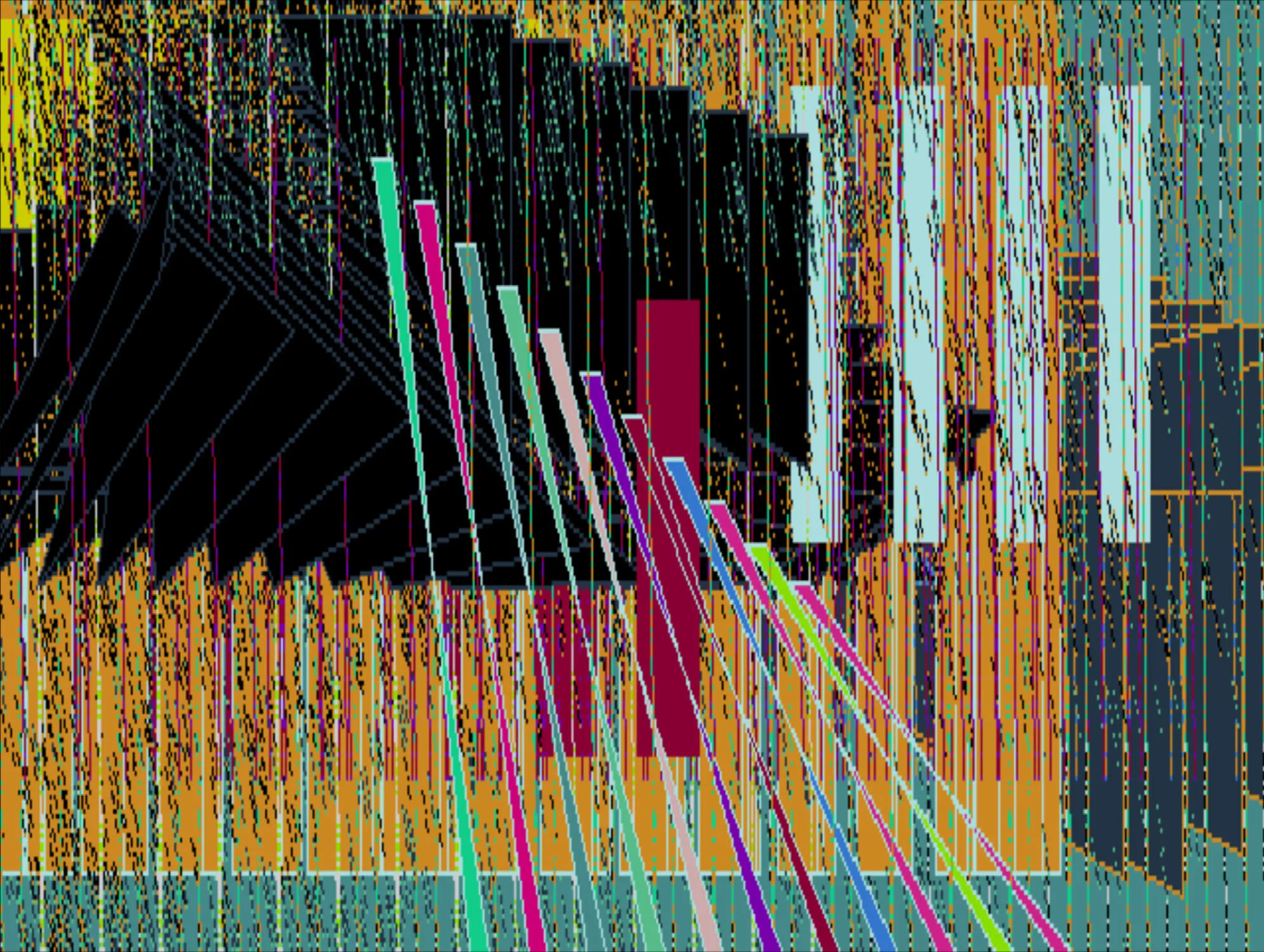

Dara Birnbaum, Pop-Pop Video Kojak Wang, 1980. Courtesy of Mudam Luxembourg

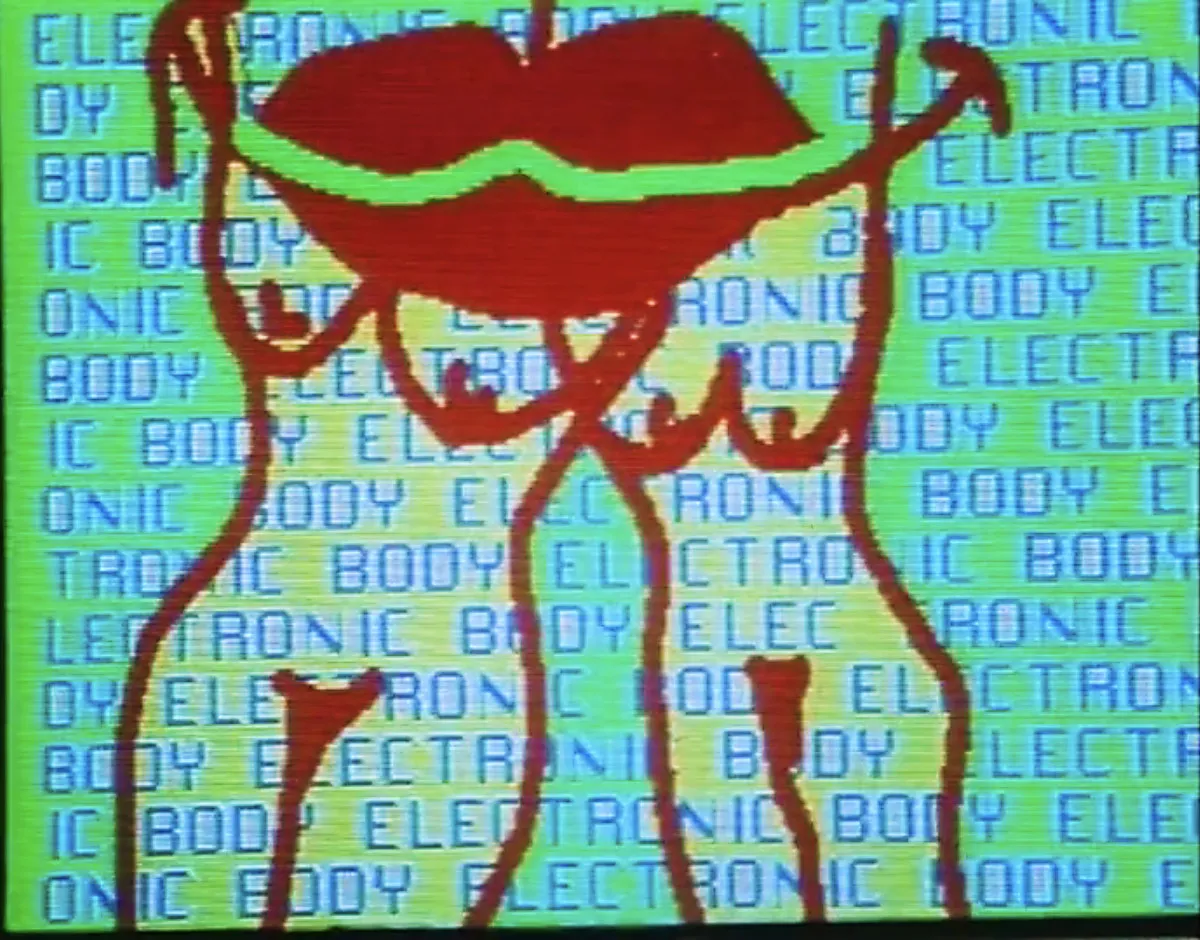

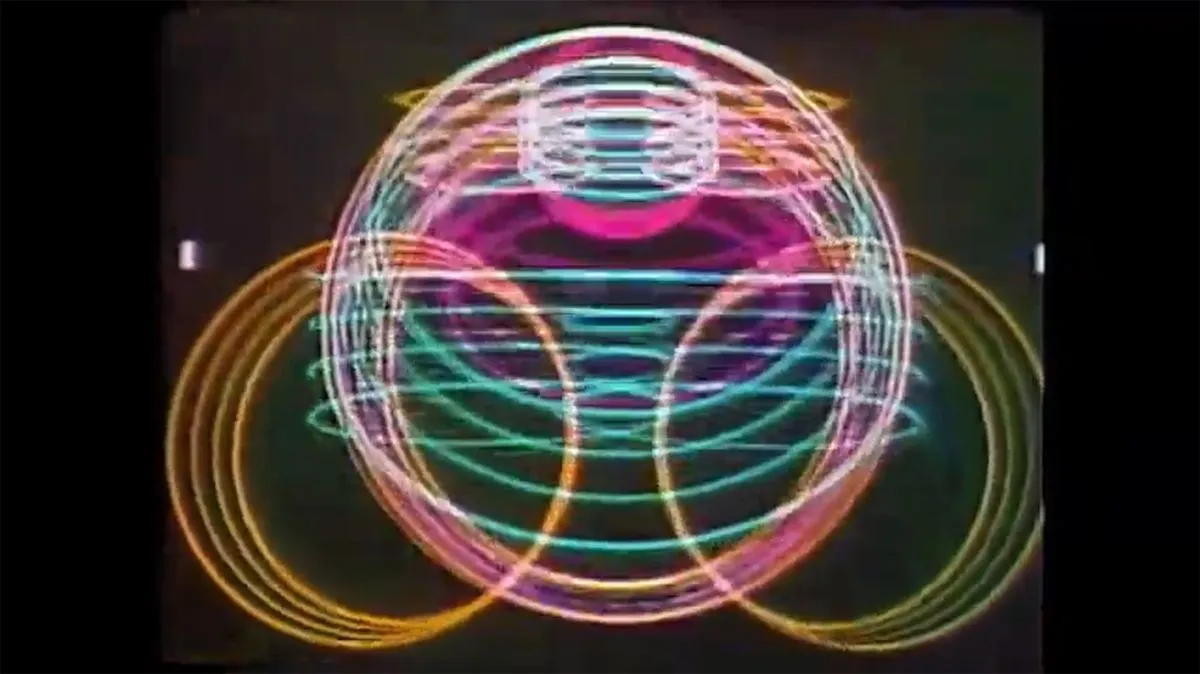

Dara Birnbaum, Pop-Pop Video Kojak Wang, 1980. Courtesy of Mudam Luxembourg 'ELECTRONIC BODY,' 'EROTIC TEXT,' and 'EROTIC ART,' flash in red and green on the screen in Barbara Hammer's video piece No No Nooky T.V. (1987). Preceded by an animated drawing of two naked women bodies, the video explores the relationship between machines and the human body, unfolding within a homoerotic narrative where the Amiga computer (amiga meaning female friend in Spanish) and the artist take center stage. The work is one of many created by women artists, early pioneers of computer art.

A prevailing trend in the art world can be best captured by the word 'rediscovery.' Among the most prominent 'rediscoveries' in recent years have been forgotten women artists who, due to gendered biases, remained on the margins and were largely unknown to the wider public. When Linda Nochlin famously questioned the absence of great women artists, she also emphasized the role of social conditions as a determining factor in their exclusion. In reshaping the narrative, the conditions of production, material, and societal norms came to be understood as critical, stirring a new direction in curatorial approaches.

The ongoing exhibition at Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean dedicated to women pioneers of computer art continues on this trajectory by offering a fresh perspective on a neglected segment of art history. Titled Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991, the show places the computer at its centre, highlighting women artists who embraced this technological innovation as a tool for creative expression.

Spanning the period from the advent of integrated circuit computing in the 1960s to the launch of the World Wide Web, the exhibition showcases how women artists used this innovative tool, tracing their artistic achievements through the computer's developmental phases, from early computing technology, through the expanded possibilities introduced by microprocessors, to the transformative revolution of microcomputing that made home computers widely accessible in the 1980s.

This is the first exhibition to approach the topic through a feminist lens, aligning the history of computing with the emergence of second-wave feminism and celebrating women artists who championed the creative possibilities of these new technologies.

"Now is the moment to present a show like this – appraising overlooked female artists of the twentieth century – who, often excluded from traditionally male artistic domains such as painting, turned to the then new field of technology. Women have been leaders in digital art in the twentieth century – yet the tradition of women in technology is a largely invisible part of Western art history. We want to make it visible," said Mudam Director Bettina Steinbrügge.

The interest in industrial innovation and new technologies is not foreign to artists. From the Impressionist depictions of trains and train stations to Futurists' fascination with speed and machines, artistic imagination closely followed technological advances, discovering ways to apply new industrial aesthetics in their practice.

However, computer art differs from these previous explorations as it includes new technologies in the process of art making, instead of relying on old media.

One of the pioneers of new art, artist Rebecca Allen, explains this fascination. "In the early 1970s, I was inspired by early twentieth-century art movements such as the Bauhaus, Constructivism, and Futurism. They were looking at the technologies of the machine age and using new tools to make new forms of art but also reflecting on how machines were affecting society thought the computer age could be the next stage for creating a new form of art."

The analogue exhibition focusing on digital art at Mudam highlights the work of around 50 women artists through 100 pieces created with the help of computers. It traces the history of digital art through a feminist perspective in a refreshing attempt to reshape the dominant narrative in the field.

Radical Software also reveals the processes and topics made available through this new medium, in a display including sculptures, installations, film, performances, paintings, and many texts and drawings generated by computers.

In 1970, a new magazine was launched, focusing on the latest technologies titled Radical Software. In the introduction of the first issue, the editors explained that humanity could survive only through the humanization of technology, and the implementation of alternate information structures that would support "alternate systems and life styles."

"Our species will survive neither by totally rejecting nor unconditionally embracing technology – but by humanizing it; by allowing people access to the informational tools they need to shape and reassert control over their lives."

Established by Beryl Korot, Phyllis (Gershuny) Segura, and Ira Schneider, the magazine—after which the exhibition takes its title—argued for social change through innovation, and predated the open information model of the web era.

The sentiment of the magazine is reflected in cyberfeminism, which envisions a new, ideal citizen of the world in Donna Haraway's cyborg—a hybrid of machine and organism that the feminist theorist introduced in her influential Cyborg Manifesto (1983). Developed in the 1990s, cyberfeminism explores the relationship between technology, gender, and media, and envisions cyberspace as an important arena for fighting patriarchy and empowering women.

Women artists who experimented with computer art, as forerunners of this social movement, emphasized an experimental and experiential approach to technology, foregrounding female-centered perspectives.

In contrast to a scientific approach rooted in cold rationality, their art often incorporates chance, chaotic, and surreal elements, challenging conventional parameters of productivity and computational thinking.

In doing so, their art humanizes technology—as the founders of Radical Software propositioned—by forgrounding alternatives.

An important segment in considering the socio-political history of computer and digital art is the trajectory of programming, from the early technological developments to its more advanced phases in the postwar years. As noted by researchers, female 'flesh and blood' computers—meaning women working in early programming and mathematics, such as Maria Mitchell and Grace Hopper—were prevalent in the emerging industry, as ‘software’ was considered the female arena.

This feminization of technology led to the predominance of women in early programming, although this did not mean that they could easily access hardware. Therefore, their early works emulated computational processes in analog form.

Early examples of using a binary system and algorithmic principles can be found in Vera Molnár's machine imaginaire, Hanne Darboven's Schreibzeit, and Elena Asins's paintings and drawings. Before gaining access to computers, these artists used drawing and painting to generate patterns, exemplifying a programmatic approach and computational systems in their oeuvres.

Another important aspect of early computer art was the focus on materials; the information age would become defined by mass dematerialization, and artists seemed to react against what was to come by foregrounding hardware and its material aspects. This is visible in the dark, pronounced forms of Deborah Remington's paintings and those generated by computers by Miriam Schapiro.

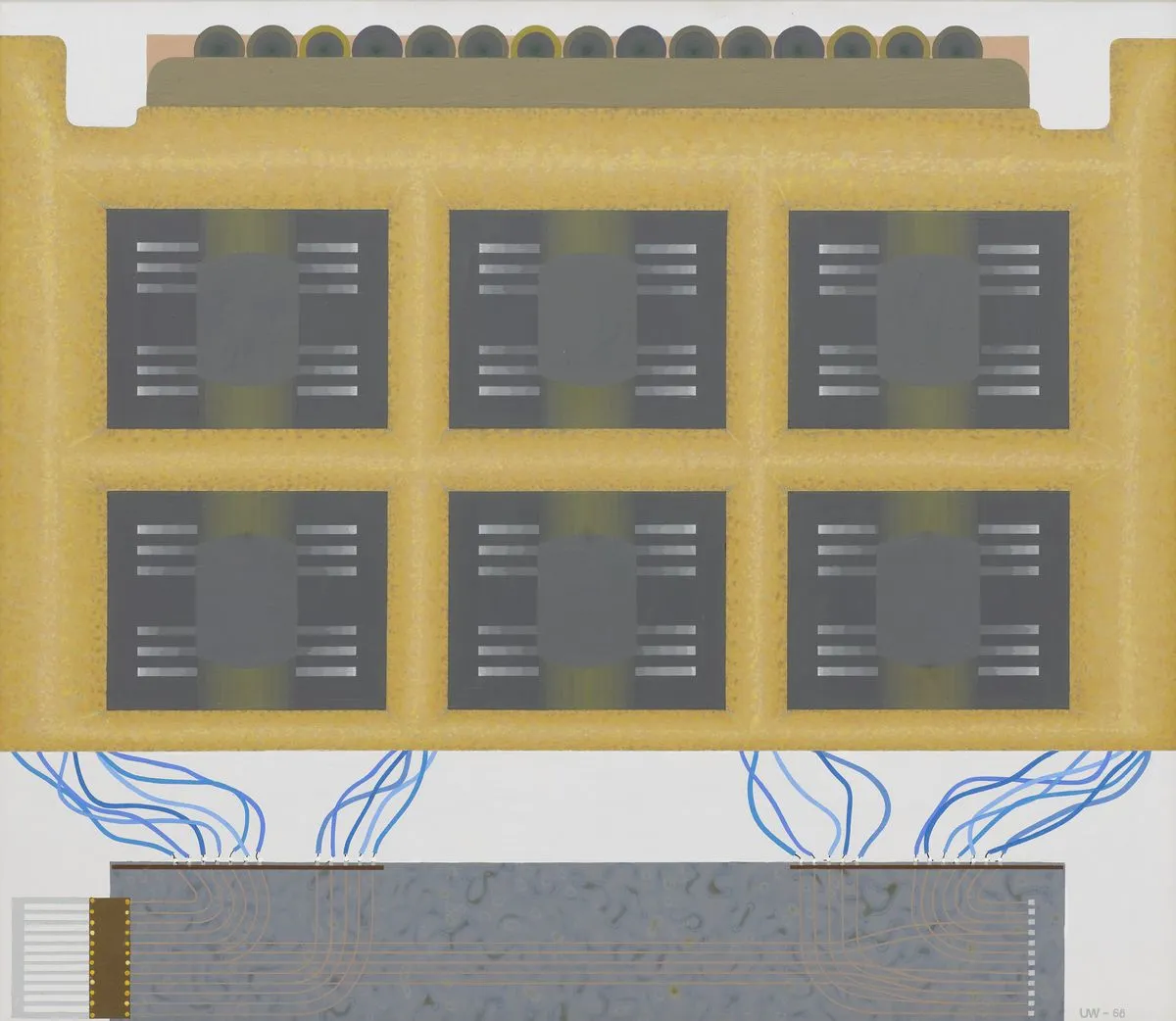

The exploration of the link between the machine and the corporeal is also evident in the works of Katalin Ladik, Irma Hünerfauth, and Ulla Wiggen. The iconic representation of this trend is Wiggen's 1968 painting Översättare, which combines hard-edged geometrical patterns with organic forms on the canvas.

A set of works by women artists is also paradigmatic for its incursion into the masculinized understanding of new technology, upending its paradigm of rationality and logic. Alison Knowles's Fluxus project House of Dust and Agnes Denes's Wittgenstein’s Pain are among the works that challenged the canon through chaotic and corrupted renderings of literature and poetry, turning computers from 'thinking machines’ into disorderly and unpredictable ones.

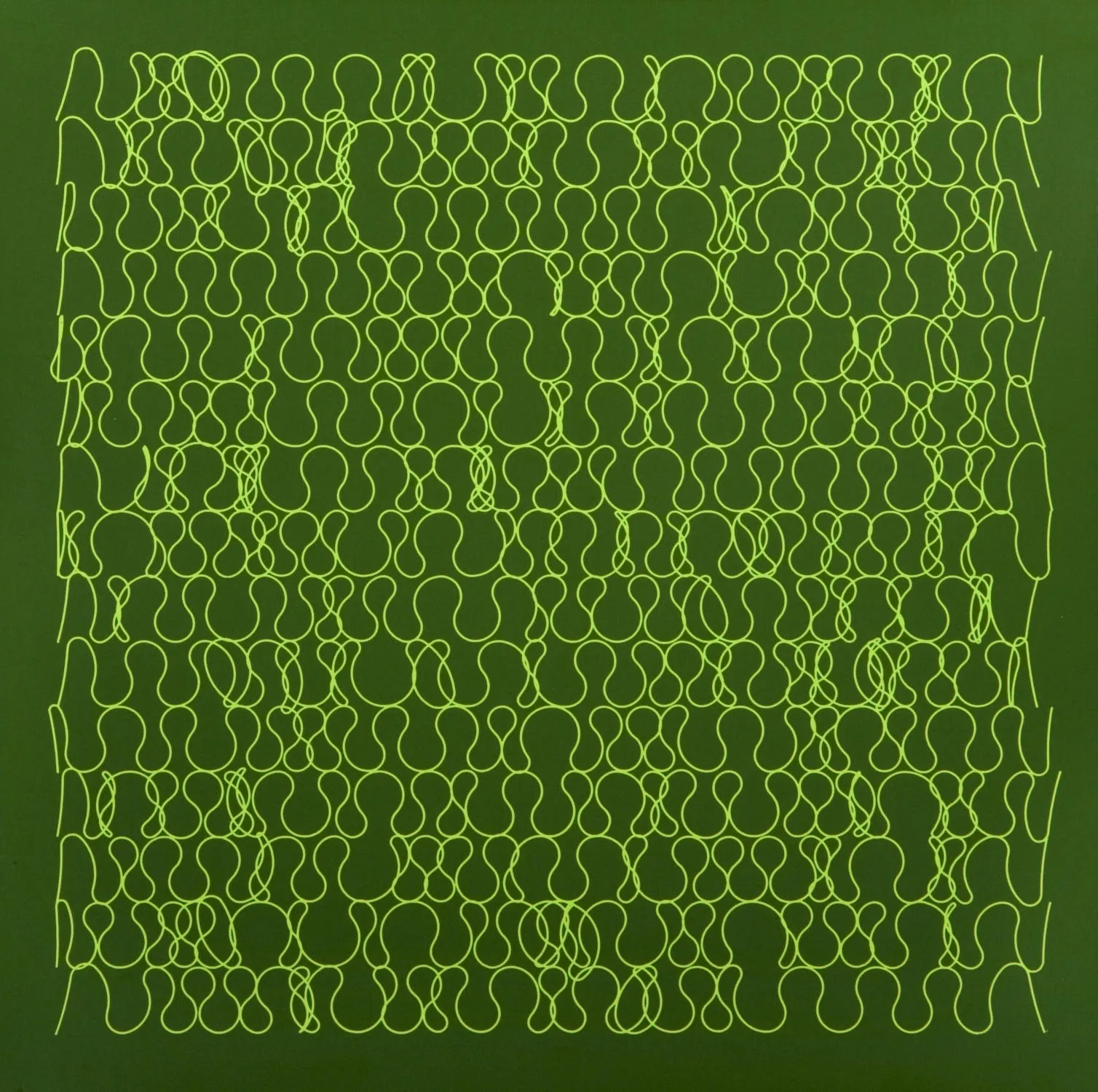

Beryl Korot's installation Text and Commentary perhaps best summarizes the tendencies within women's computer art. Inspired by and drawing from weaving and its grid structure, the artist combines videos with textile panels where woven cloth sets the structure of video information.

However, the work's politics does not rely solely on this correlation of patterning; more significantly, Text and Commentary links two practices within the feminist narrative, where weaving and computing continue on the same trajectory of female creativity and expression, and "against the one code that translates all meaning perfectly, the central dogma of phallogocentrism," according to Haraway.

The machine is us, our processes, an aspect of our embodiment.

By foregrounding women's contributions, the exhibition challenges the male-dominated narratives that have long shaped digital and computational art history. Many of these artists not only experimented with the aesthetic and conceptual potential of early computing but also engaged critically with the social and political implications of technology. Their work refutes the idea that digital art developed independently of feminist discourse, instead demonstrating how questions of authorship, labor, and agency have shaped the field from its inception. Among the pioneering figures featured in the exhibition, we highlight those whose work exemplifies these ideas.

Hungarian artist Vera Molnár is praised for establishing the parameters for art and technology interaction, grounding her method in a system-based approach and geometric abstraction. Before gaining access to computers in 1968, she manually executed algorithmic processes. At the root of her practice was her untiring search for the evidence of art in simple forms. In this, computers played a crucial role.

I use simple shapes because they allow me step-by-step control over how I create the image arrangement. Thus, I can try to identify the exact moment when the evidence of art becomes visible. In order to guarantee the systematic nature of this research, I use a computer.

Starting with computer animation in the 1970s, Rebecca Allen explored the relationship between art and technology, inspired by modernist movements. Her early works include Girl Lifts Skirt (1974) and the groundbreaking Swimmer (1981), the first 3D animation of a female figure in motion. She also collaborated with the German electronic band Kraftwerk.

"I would say I've been a feminist my whole life, in the sense that I’ve been very aware of being a woman and intentionally breaking new ground in places where women weren’t supposed to be – both in art and technology," she explained.

I’ve tried to create a new aesthetic for our modern time while addressing profound issues.

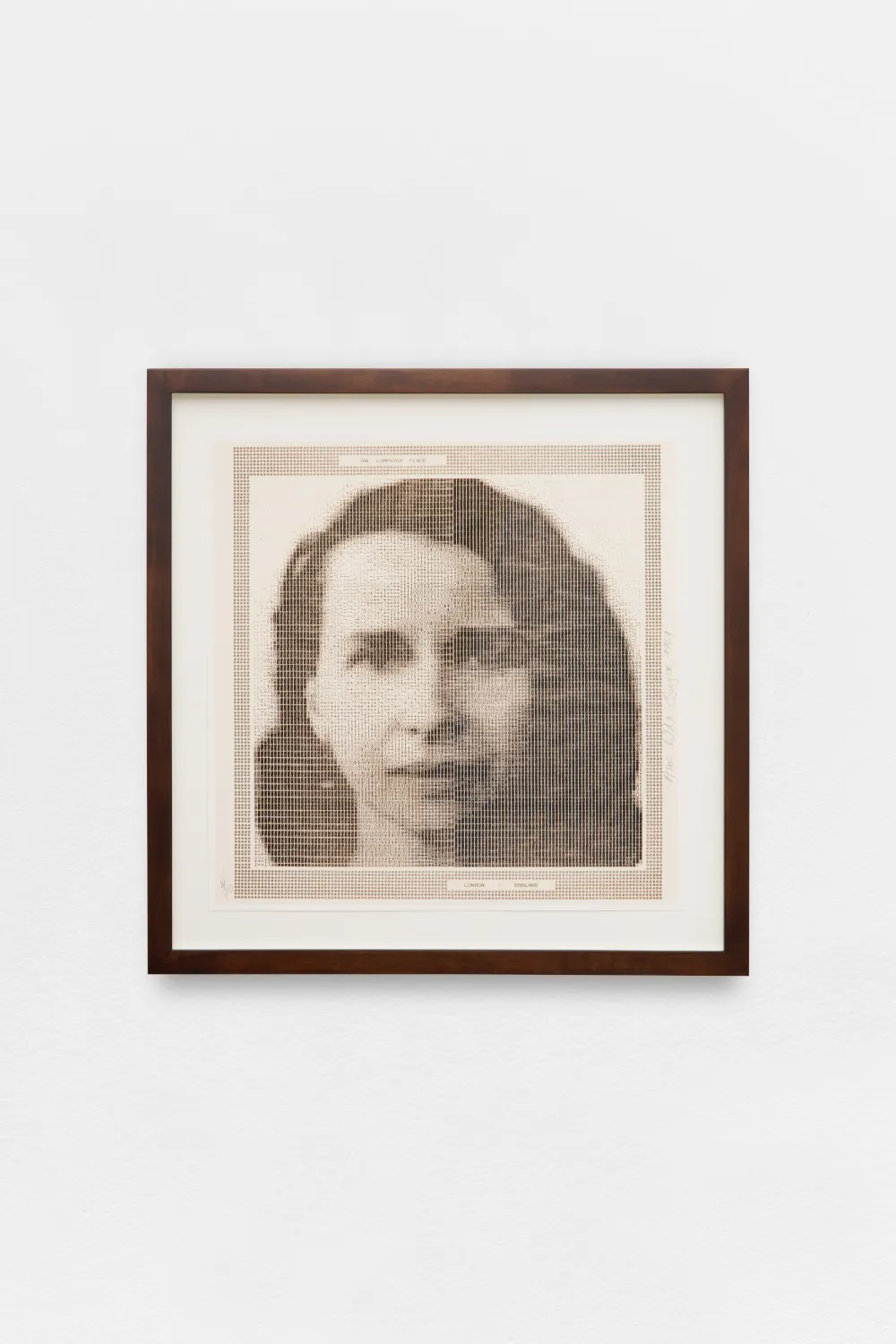

Lillian Schwartz, one of the earliest computer artists, first gained recognition for her kinetic sculptures before being introduced to Bell Laboratories by Leon Harmon, where she developed her career in computer art.

Recognizable for her combination of drawings and filmed footage with computer-generated images, she later published The Computer Artist’s Handbook (1992), in which she explained her approach.

I had to push the early machine and cajole scientists to make the computer an art tool.

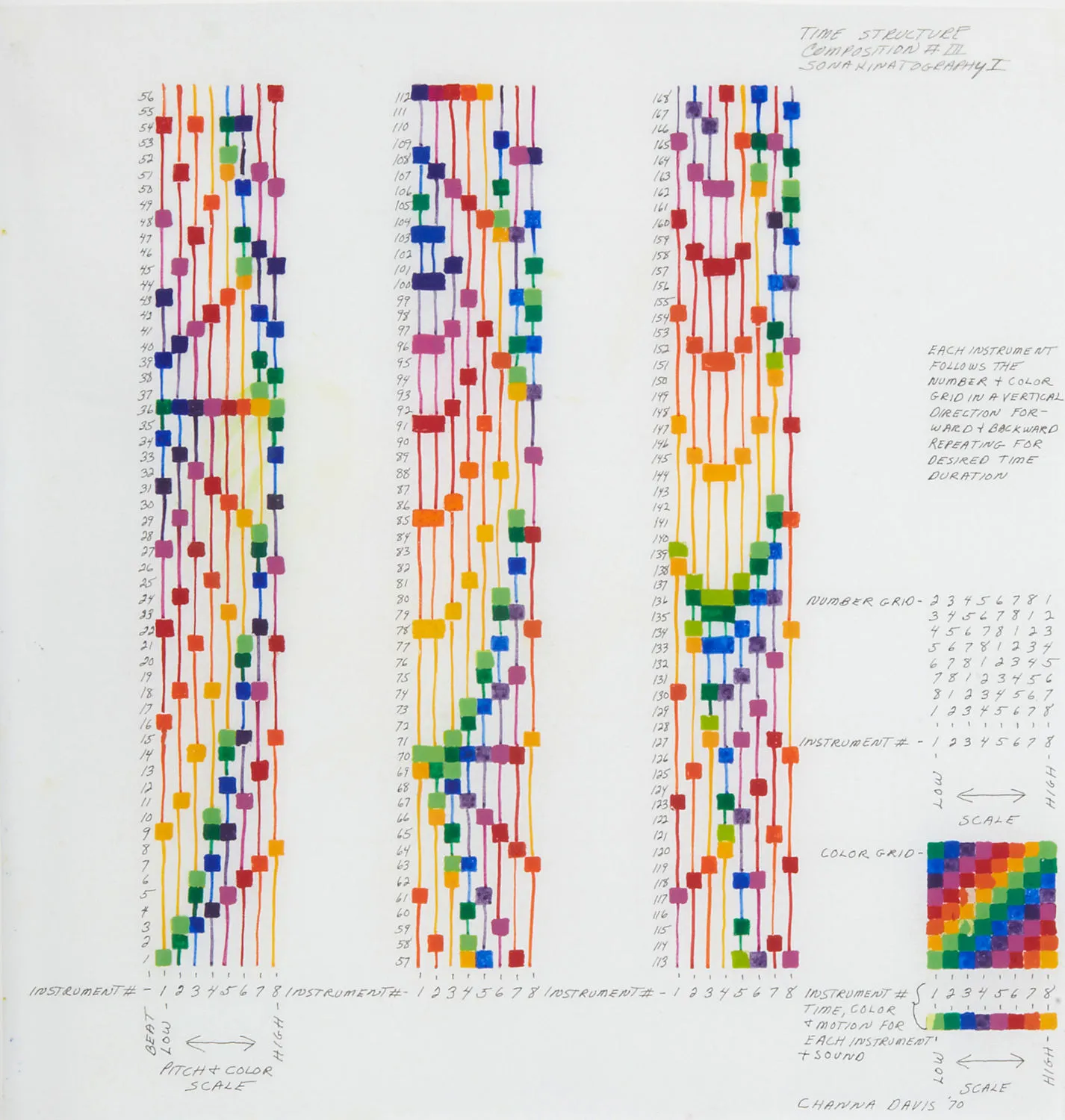

"1978 was the year I traded my loom for the first ‘personal’ computer," Charlotte Johannesson recalled about her start in computer art. Inspired by the structural similarities between weaving and digital image-making, she explored the role of computers in art and later co-founded Digital Theatre in Malmö, Scandinavia's first digital arts lab, with her husband Sture.

Recalling the skepticism she faced, she said, “The computer was really considered the devil's tool amongst people in the arts.” For some critics, it was not art at all. Johannesson's practice is defined by a fusion of craft and computer graphics.

The computer that propelled Samia Halaby into digital art was the Amiga 1000, which she used to create abstract art—a shift that profoundly influenced her approach to abstraction.

“In 1985 I told myself that if I were an artist of my time, I should explore the technology of my time,” she recalled.

Her digital works, which she called 'kinetic paintings,' captured her environment while also serving as repositories of memory. For example, her digital series Yafa is dedicated to the Palestinian town where she spent her formative years. However, her origins proved to be a stumbling block in her career.

"I was not known then, and I was not accepted in the New York art world due to hostility towards Palestinians."

Despite these challenges, she remained steadfast, though she faced censorship last year when Indiana University abruptly canceled what would have been her U.S. museum debut.

A Yugoslav pioneer in performance and sound art and poetry, Katalin Ladik began experimenting with technology early, following her stint as a radio actress. Sound has remained an integral part of her works, which transcend traditional artistic boundaries.

"In Yugoslavia, as early as the late 1960s, I performed graphic scores by some avant-garde composers at music festivals," she explained about her early years.

Her neo-avant-garde practice integrates poetry, folklore, mythology, and the body, challenging established gender norms and artistic traditions.

First and above all, I am a poet. I always convey a poetic message through […] voice poetry with my voice, concrete poetry with my visual works and collages, and multimedia poetic performances with my body.

The legacy of women in computer art is a testament to resilience, innovation, and creativity in the face of gendered barriers. Tracing their engagement with technology from early programming to the rise of cyberfeminism, Radical Software reveals how these artists not only experimented with computational aesthetics but also critiqued the social and political dimensions of technology.

Their exploration of technology as a tool for artistic expression not only challenges the traditional boundaries of both art and technology but also provides critical perspectives on the intersection of gender, identity, and digital media. As the conversation around representation in both fields grows, the contributions of these women stand as a powerful reminder of the need to amplify diverse voices and redefine the future of art in the digital age. By reclaiming their place in art history, Radical Software underscores the continued relevance of their work in shaping contemporary discussions on digital culture, authorship, and feminist discourse.

The exhibition Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991 is on view at Mudam Luxembourg – Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean until February 2nd 2025, after which it will be presented at Kunsthalle Wien from February 28th until May 25th, 2025.