Adrian Pepe, 2022. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Adrian Pepe, 2022. Photo courtesy of the artist. What does it mean for a material to remember? For a thread to bear the weight of history, or a textile to echo gestures of care, rupture, and repair? In Adrian Pepe's work, fiber is not merely a medium—it's a language, a witness, and a vessel for transformation.

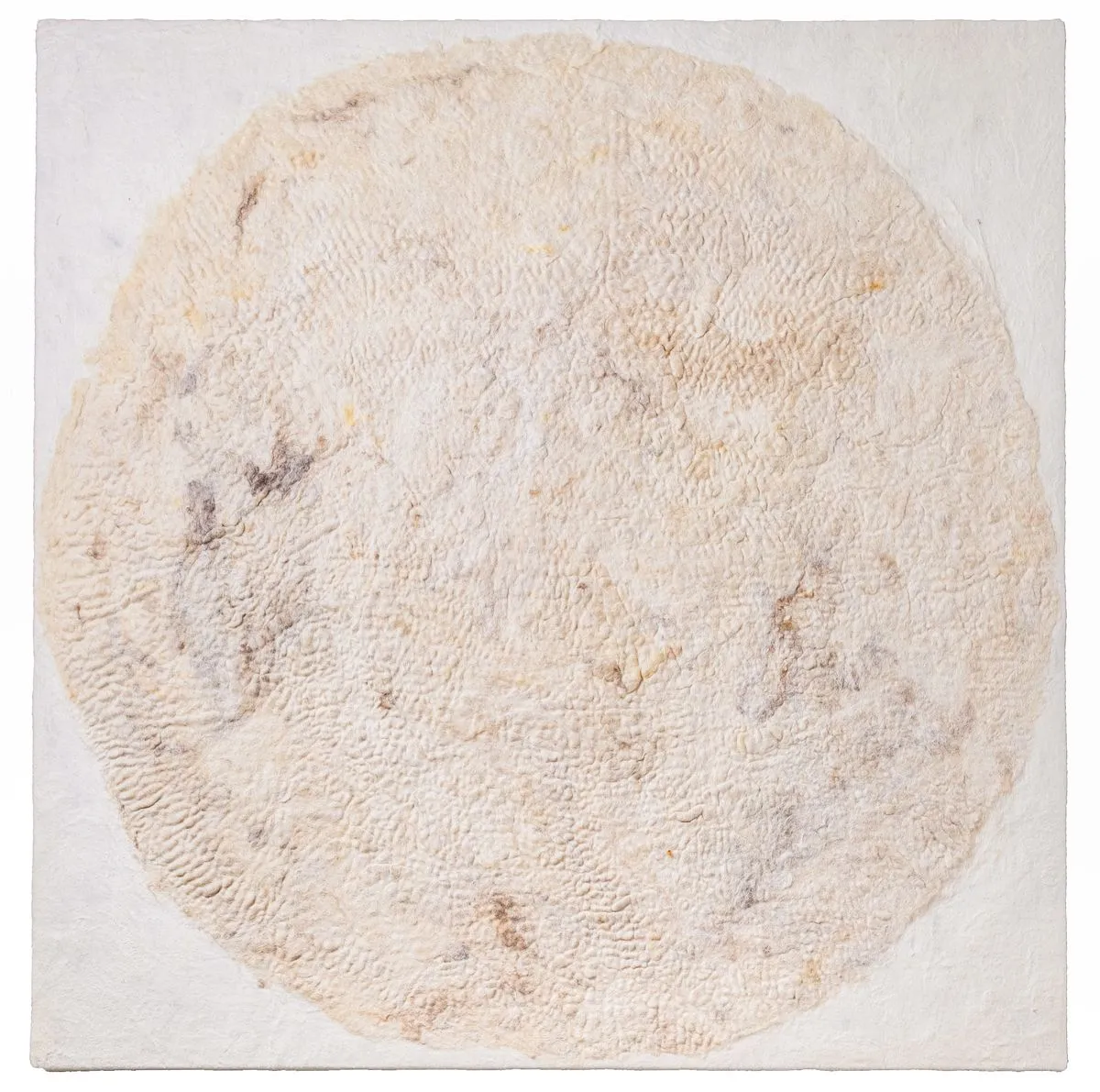

Pepe's practice moves between the intimate and the monumental, the ritual and the infrastructural. It weaves together ecological memory, collective grief, and the embodied nature of labor. His installations, performances, and craft-based processes ask how materials—especially those tied to survival, like wool and jute—carry and transform meaning. Working primarily with wool, he moves through cleansing, felting, spinning, and stitching—each stage a quiet act of attunement. Debris like dirt, seed diaspores, and insects is left intact, forming a kind of living archive: markers of life, place, movement and proximity.

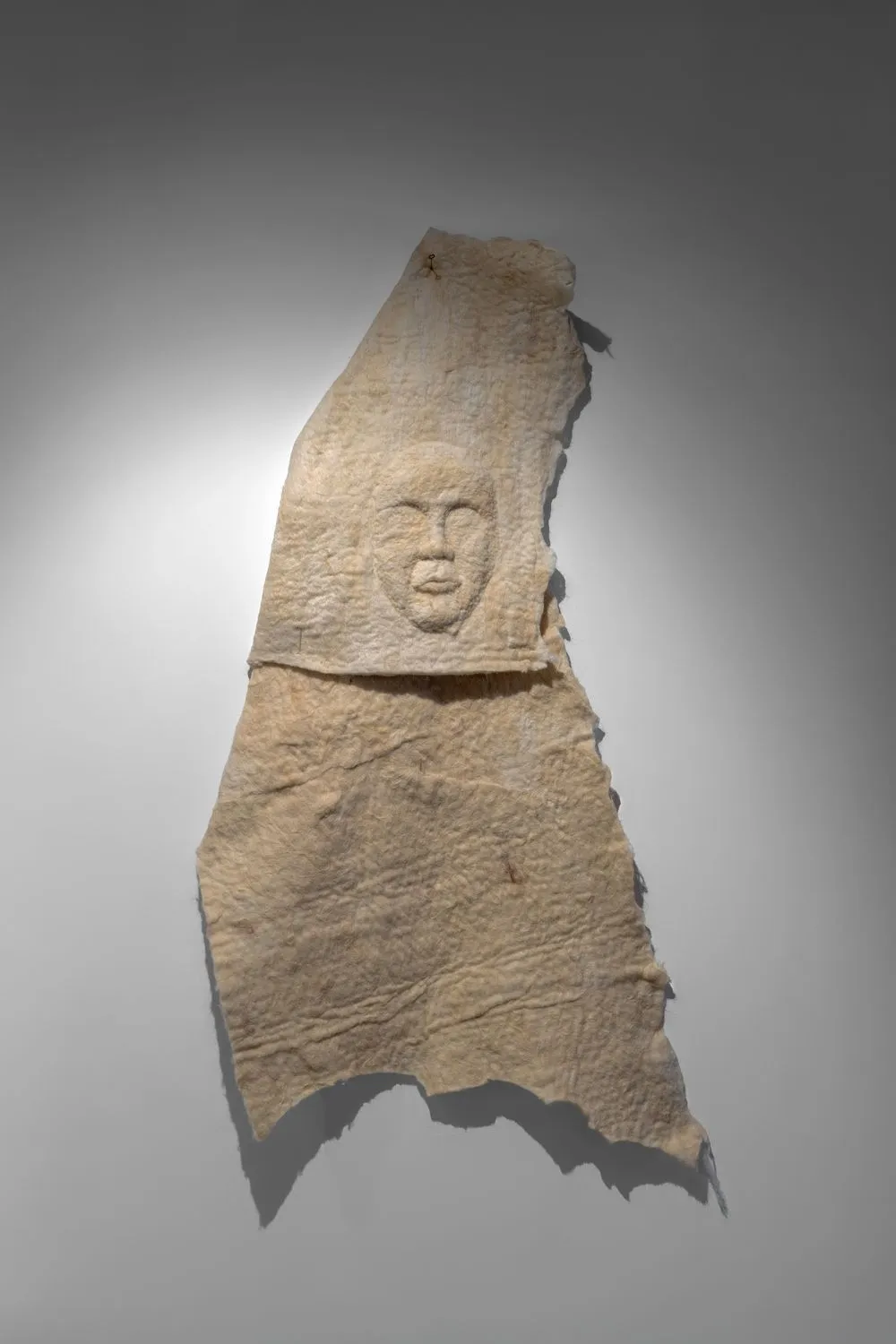

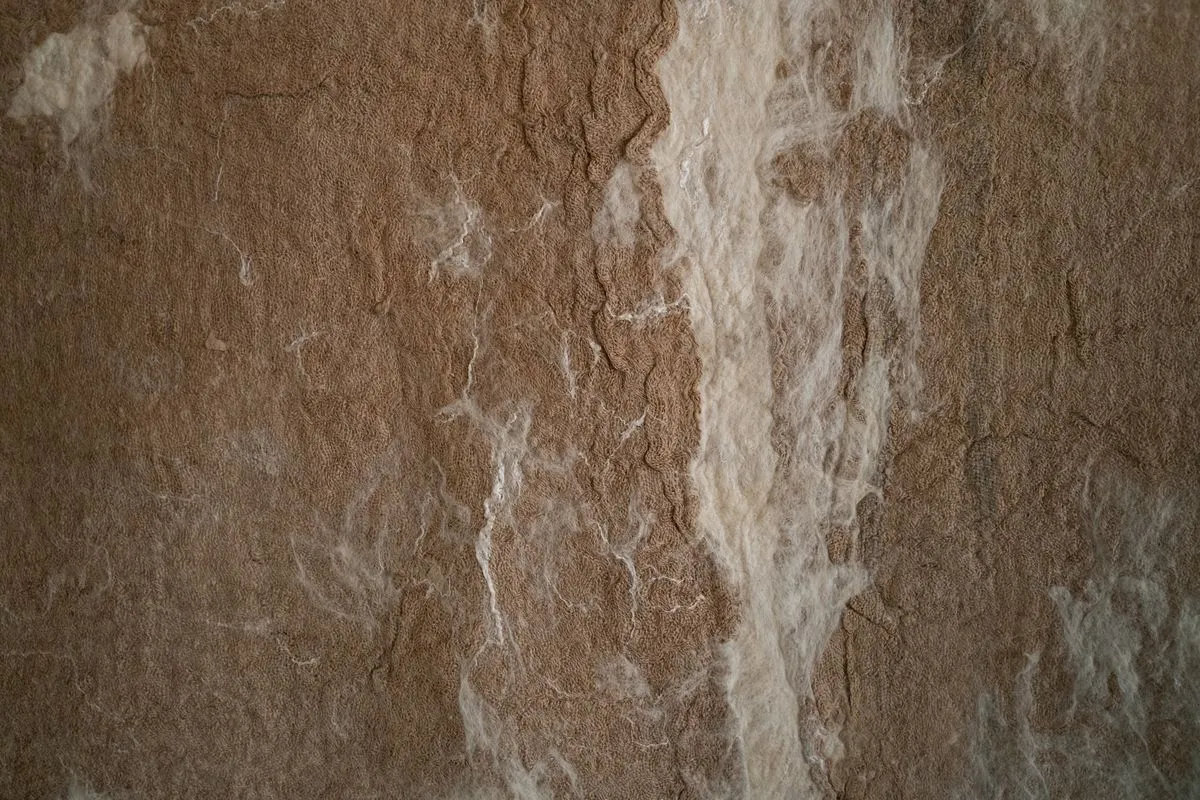

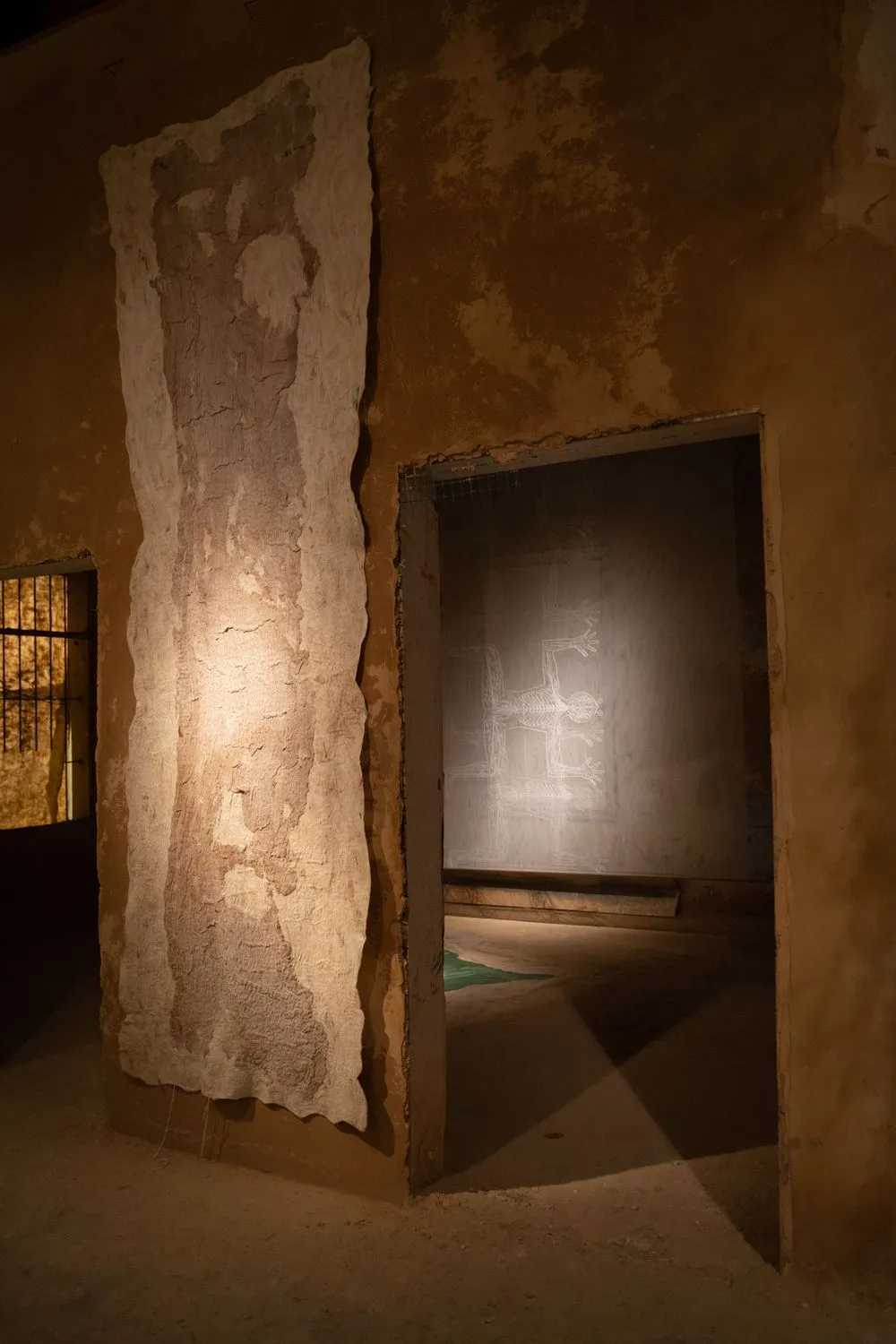

In A Shroud is a Cloth, on view at NIKA Project Space in Dubai, Pepe draws us into a world where fiber holds memory and making becomes a form of listening. The exhibition centers on a vast woolen textile that once wrapped a damaged heritage building in Beirut—an object both protective and permeable, steeped in the trauma and resilience of place—but this is only one part of a wider body of work. Through gestures of felting and stitching, Pepe reworks this cloth alongside other pieces into votive forms, intimate surfaces, and monumental structures. We encounter not just wool, but an ecology of relations: between body and environment, ritual and repair, past and possibility.

Wool has this capacity to hold time—it is resilient yet malleable, intimate yet expansive. In this exhibition, I am exploring how materials are never neutral; they shape, and are shaped by care, labor, and the environments they inhabit.

From enveloping damaged architecture in hand-felted wool to crafting quiet sanctuaries charged with memory, Pepe's work invites us to see textiles not as static objects but as living witnesses. At NIKA, his first solo exhibition with the space, he invites viewers into a quiet, tactile space of reflection—where fibers speak, and the act of making becomes a form of listening.

"The body becomes a surface," Pepe says. "What remains is a trace of relations." In this interview, he reflects on material memory, the entanglement of bodies and environments, and how wool, labor, and debris carry the imprints of shared experience.

Jelena Martinović: Your exhibition at Nika Project Space expands the idea of a shroud beyond its traditional meaning. What drew you to this notion of textile as a marker of transformation?

Adrian Pepe: A shroud marks transition. It conceals and protects. I was drawn to this duality, especially in how textiles—through their proximity to the body—become witnesses to change. The shroud became a way to think about the shifting quality in things.

JM: The textile at the heart of the exhibition carries with it the history of the 2020 Beirut Port Explosion. How do you see the act of transforming this material as a form of healing or repair?

AP: Wrapping the building in wool was less about fixing something broken and more about acknowledging its state. Wool as well as other fibers, have been used within the context of bandaging and protection of the body. I intended to draw a parallel between the human body and the urban body—both vulnerable, in flux. The textile became a marker of stages within that process.

JM: Wool is central to your exhibition, carrying both material and symbolic significance. What draws you to wool as a medium that holds memories and reflects change?

AP: My interest isn't limited to wool—it extends to the animal itself, and to the human-animal relationship that's developed over time. These bonds shaped not only materials of survival, but entire systems of belief, labor, and ritual. Wool is part of that larger inquiry. I'm interested in what material can carry, what remains in it from those relations, and how that residue shapes the way we live with and through it.

JM: Your work involves cleansing, felting, stitching, and assembling wool, preserving the debris it carries along the way. Can you walk us through this process and what each stage brings to the work?

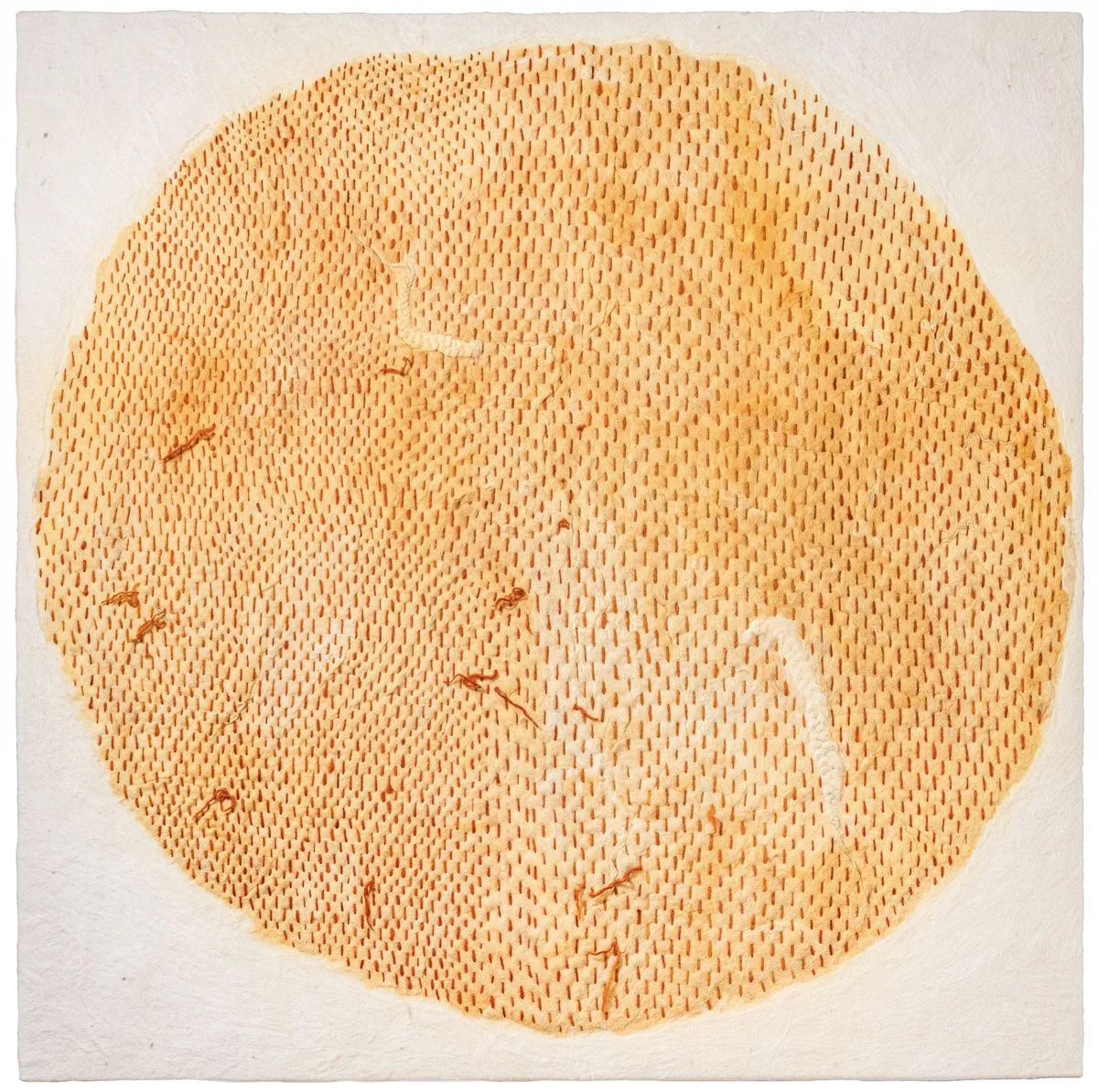

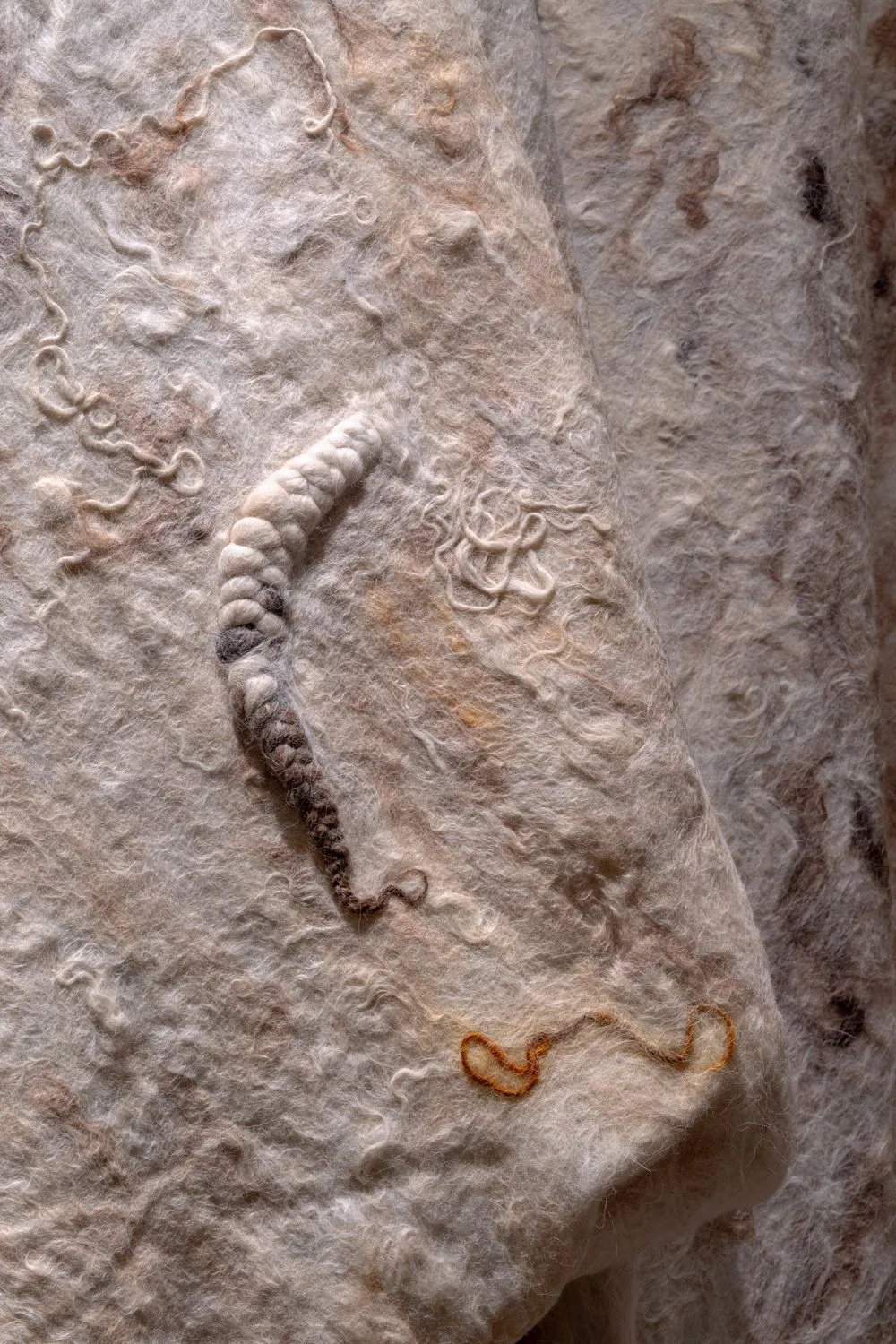

AP: The process is seasonal. It begins in spring or early summer, when the sheep are shorn and the fleece—the full coat—is removed. The raw wool is then collected and cleansed through steps like willowing and combing, which start to separate the fiber from the landscape it has moved through. This stage is about making the fiber workable—isolating it while also gathering the seeds, dust, and other remnants caught within it. These fragments are later categorized, forming part of an evolving taxonomy of the material's ecology.

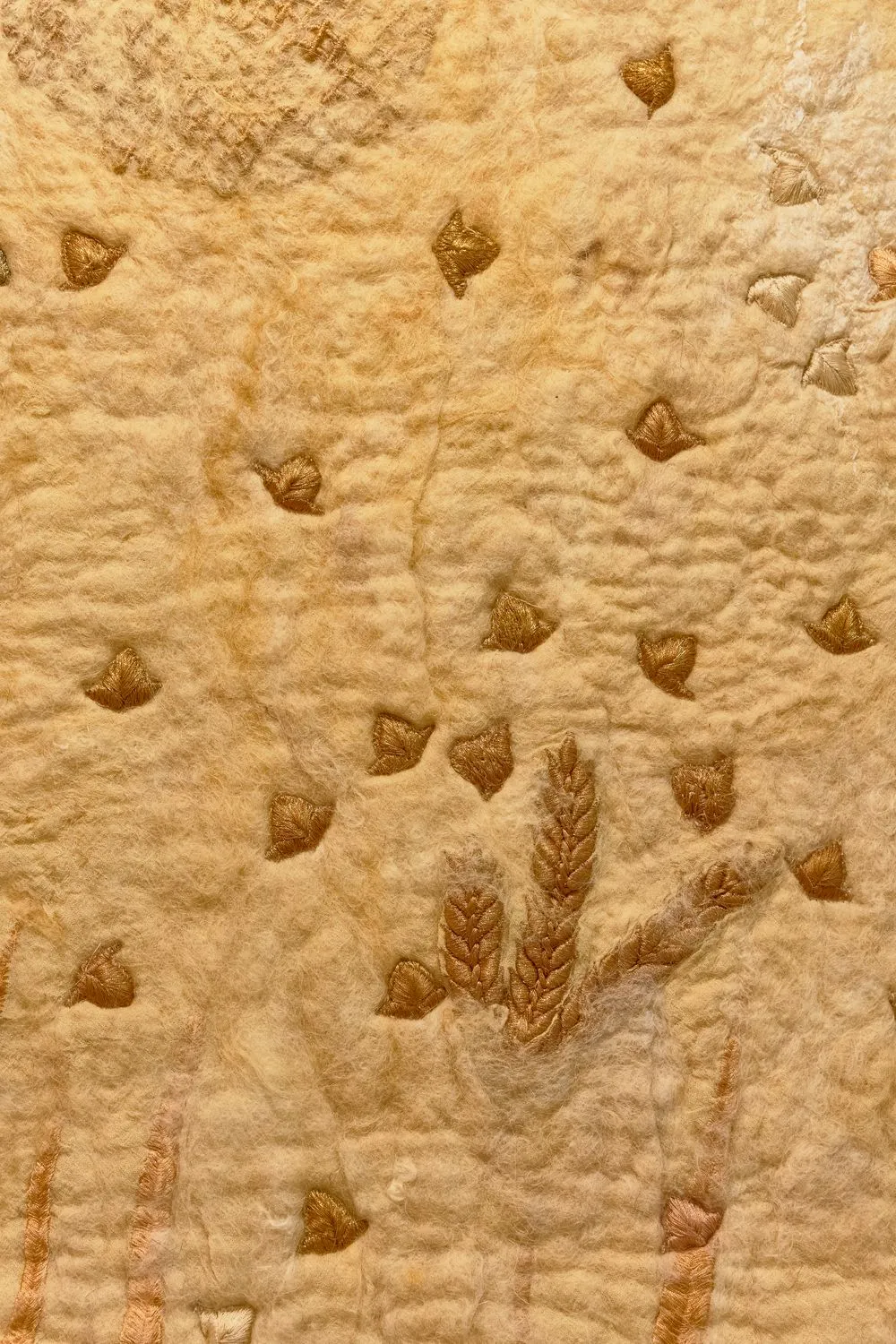

Spinning and felting follow, reintroducing structure to the loose fiber. Felting binds the wool using friction, moisture, and heat—transforming it into a dense, cohesive surface. Embroidery is occasionally layered on or in and partially absorbed, creating moments of concealment and revelation. Dry felting and stitching add further texture, carving topography into the surface.

JM: The act of felting is labor-intensive and communal. How important is the process itself in your work, especially in relation to ideas of care and collectivity?

AP: The process is a site of inquiry. It doesn't begin with the making of the final work, but in the relations that make the work possible: between bodies, materials, environments, and time. The gestures accumulate, and what's left behind—the object—is a residue, a trace of relations.

JM: How does the collection and preservation of debris—such as seeds, dust, and insects—from the wool function as an archive of the landscape in your work, and what does it reveal about the relationship between humans and nature?

AP: The debris that accumulates in the fleece—seeds, dust, insects—isn't curated; it's incidental. It collects over time as the animal moves, brushes, grazes. Hair can be viewed as a kind of tentacle—reaching, clinging, holding onto the environment. These residues speak to where the animal has been, what it's touched, what it relates to.

They form an archive, a record not just of place but of interaction. The human-animal-plant-environment relationship becomes visible in these traces. They reveal proximity, friction, and shared space—micro-evidence of how bodies cohabit and leave impressions on one another. It's also a record of the animal itself—not only its genetic makeup, but its lived experience. The fiber carries both inheritance and encounter.

JM: Shedding is a deeply physical work, both in its making and in your performance. How did the experience of being wrapped in wool change your understanding of the body as material?

AP: It became a surface, a site of labor, a substrate. The process of felting onto skin is both invasive and intimate—it blurs the line between subject and object. The body is no longer central, but something to be worked on, moved around, shaped.

JM: You often connect the concept of labor with the materiality of your work, emphasizing how care and effort shape the final compositions. How do you view the relationship between art and labor in your practice?

AP: Labor is in everything—before the object, beyond the object, after it. Some forms are visible, others go unnoticed. Some are gendered, ritualized, internalized. We inherit them. We perform them. We contain them.

There's the question of who labors, and who is allowed to stop. There's also the question of value—what kind of effort is preserved, and what kind is forgotten. Perhaps labor is not only a means of production, but a way of knowing—something we perform in order to remember, question, or remain.

JM: The materials you choose, like wool, jute, and others, seem to carry cultural and historical significance. How do you see your materials as part of a larger narrative about people, place, and history?

AP: Materials are embedded in systems: trade, ritual, utility, economy. They mark shifting relationships between land and labor, power and proximity. I observe them, interact with them to speculate—about past moments, about how meaning forms around material over time, how we can begin to consider future imaginaries.

Sometimes I work with them, sometimes against them. They're not just mediums—they're tensions, sites of inquiry. What they carry is not fixed, but responsive to context, gesture, and encounter.

JM: What role do you see art playing in times of crisis, like the aftermath of the Beirut explosion or the global challenges we face today? How can art function as a means of resistance, healing, or transformation?

AP: Art can interrupt narratives, reframe grief, or simply hold something that is hard to name—a sort of remembrance. It allows for different forms of witnessing.

At times, it functions like a cultural mnemonic—a symbolic threshold that operates both within and beyond language. It doesn’t explain, but it cues. It helps orient us.