Randolpho Lamonier in his studio. Sara Não Tem Nome and Victor Galvão

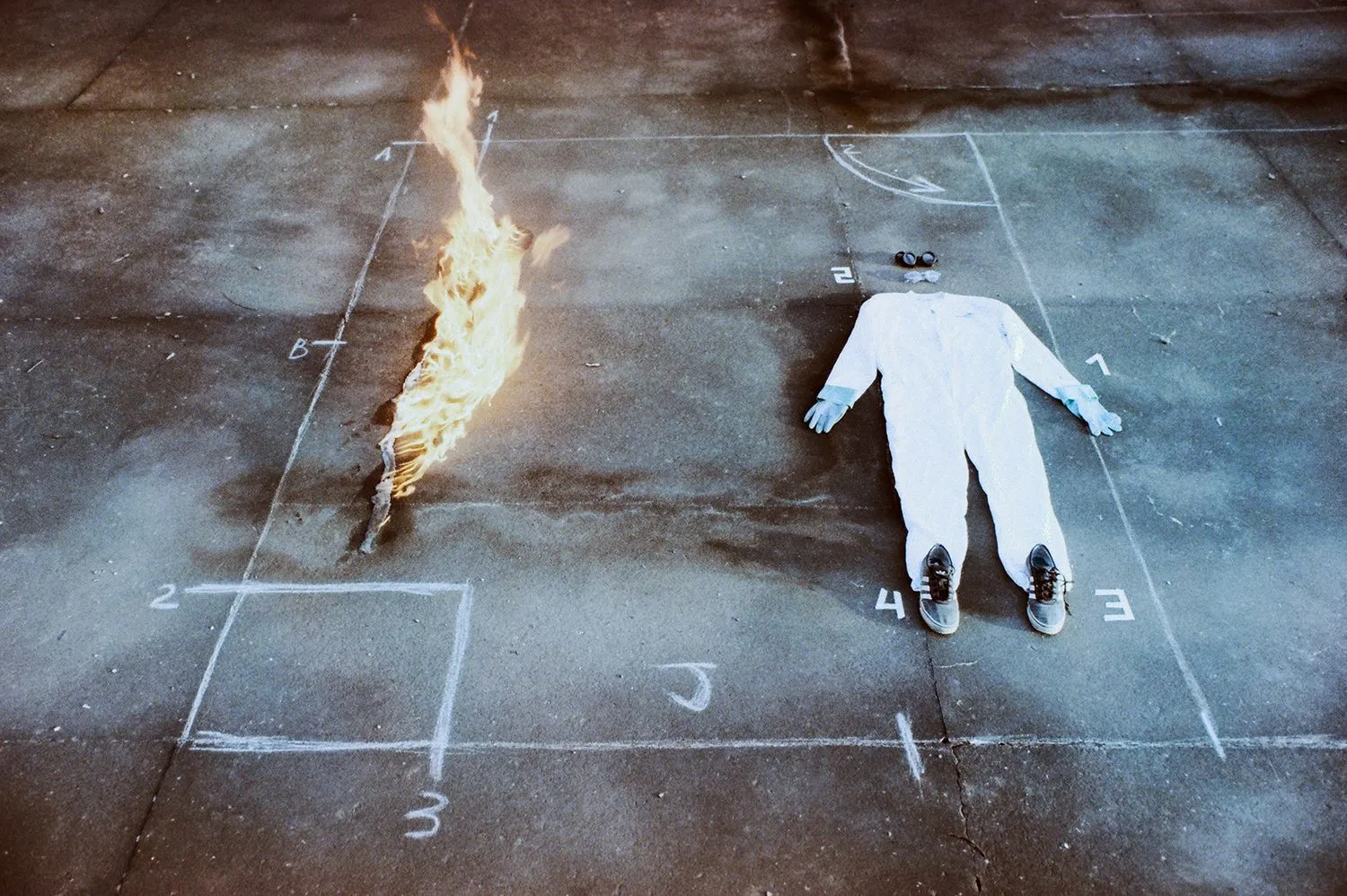

Randolpho Lamonier in his studio. Sara Não Tem Nome and Victor Galvão Randolpho Lamonier's work emerges from the margins—both geographic and social. Growing up in Contagem, an industrial city in Southeastern Brazil marked by mining, manufacturing, and systemic inequality, Lamonier learned early to navigate worlds defined by precarity and resilience. His experience as a queer youth in this hostile environment shaped not only the content of his work but its forms: an improvisational, material-driven practice that transforms discarded objects, fabrics, and everyday traces into vessels of memory, desire, and social critique.

Working across sculpture, installation, collage, photography, tapestry, and video, Lamonier treats materials as carriers of history and emotion. Sewing and embroidery, practices inherited from his grandmother and mother, allow him to fold care, repetition, and persistence into works that explore intimacy, violence, and survival. Found objects, remnants of industrial and domestic life, become metaphors for overlooked communities and stories, turning the personal into a collective mirror.

In our conversation, we explored how Contagem continues to shape his perspective, how his practice engages with the politics of urban peripheries, and the ways his work weaves personal memory into broader social narratives—transforming fragments of experience into acts of resistance, reflection, and possibility.

Jelena Martinović: Your work is deeply connected to Contagem, where you grew up. How has the city and your relationship with it shaped your artistic perspective?

Randolpho Lamonier: Contagem is an industrial city in Southeastern Brazil, located in a region historically marked by mining exploitation. Throughout the 20th century it became an important industrial pole and all of my family spent their entire lives working in industrial plants in very hard conditions. Myself included, as I worked on a manufacturing plant for a while before I was able to leave the city, seeking to study art. Growing up in such a hostile place I had to learn to see the world from its margins — the margins of the city and the official narratives. Living with inequality, violence, precarious infrastructure, and the emotional landscape that comes with all that shaped my perspective deeply. Not just in terms of content, but also in form: the interest for cheap common materials, the visible wear and tear, the layering of languages, where improvisation is a means of survival.

But there's something even more personal that cuts through all of this: I was a queer kid growing up in a peripheral context that was extremely violent — toward me and toward others like me. There was no community, no group where I could feel a sense of belonging. So art became a kind of shelter — but also a way to invent my own world. It gave me a space to grow among all that hostility.

Contagem taught me that everything communicates and, sometimes, communication is a form of survival or quiet revolt. My relationship with the city isn't merely about belonging, It's about tension and affection. It made me ask: how do you make meaning in a place where everything feels like either ruin or a broken promise?

JM: You often highlight urban peripheries and the politics of space. How does your work address the realities faced by marginalized communities in these spaces?

RL: The urban peripheries don't appear in my work as a theme or a setting — they are the very starting point. For me, talking about the politics of space is talking about struggle: for visibility, for dignity, for permanence. These territories carry a potency that deeply interests me. I try to access this potency without idealizing it, recognizing both the beauty and the harshness that mark these realities.

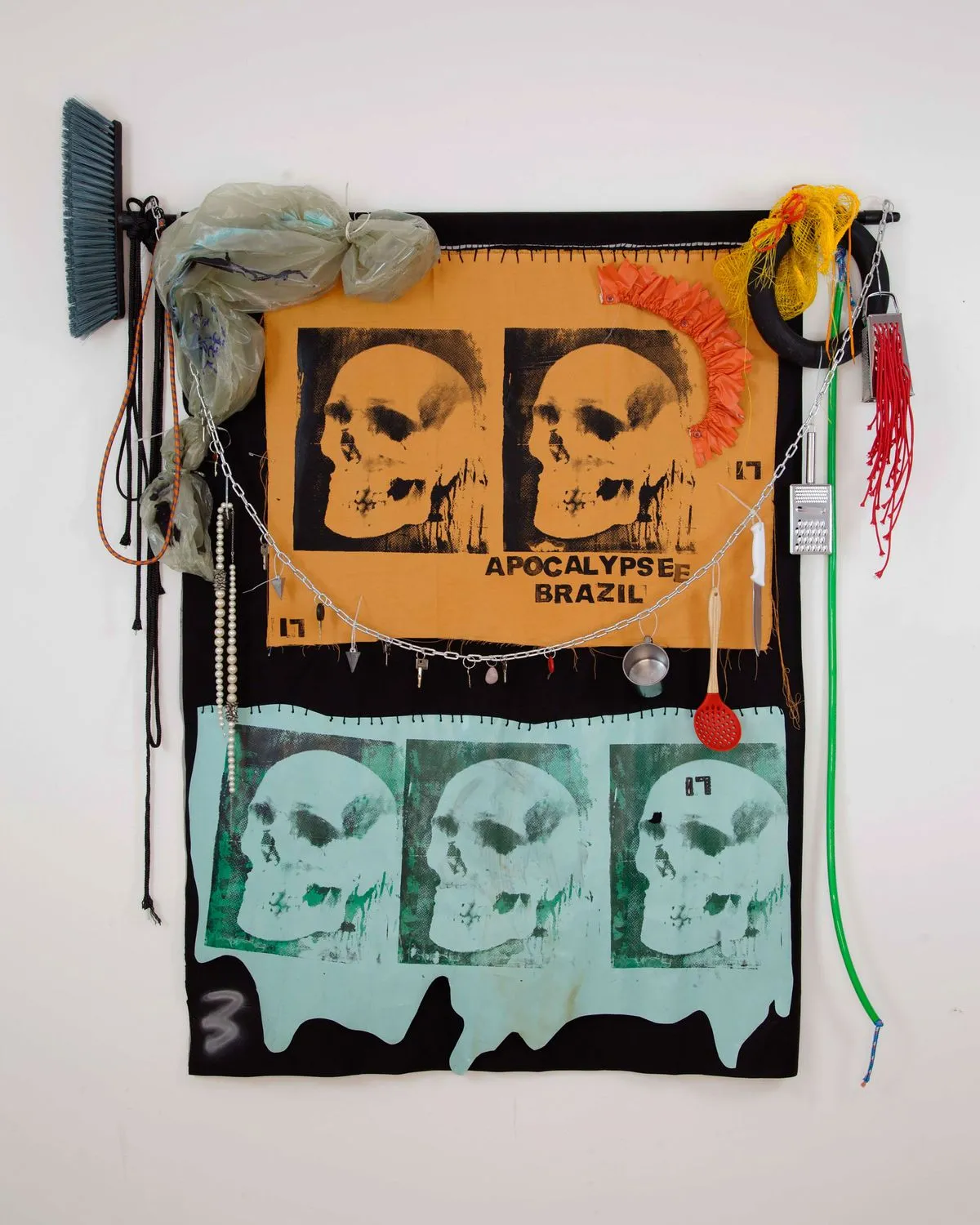

My practice seeks to challenge this condition of marginalization, not just by denouncing it, but by producing image and memory from it. Sewing, embroidery, the use of ordinary and discarded materials — all of these come as a political gesture because they challenge hierarchies of value — what is worthy of being seen, what deserves to be preserved, what can be considered artistic language. I seek to speak of everyday life, but also of desire, sometimes starting with chronicles, but also pointing toward fiction as a possibility for the future.

I try to approach themes such as violence, exclusion, desire, vengeance, friendship from my own experience. From intimate memories, traumas that still reverberate, desires that constitute me as a subject. In this sense, the personal stops being just personal. When I expose myself, when I shape these fragments of my life, intimacy becomes a political mirror. Because what's intimate is also historical, it's collective. And for me, this is a way of claiming belonging and turning pain into language.

JM: Your practice spans diverse media—from sculpture and assemblage to collage, installation, photography, tapestry, and video. How do you decide which medium to use for a specific project, and how does the choice of medium shape the themes or messages you wish to convey?

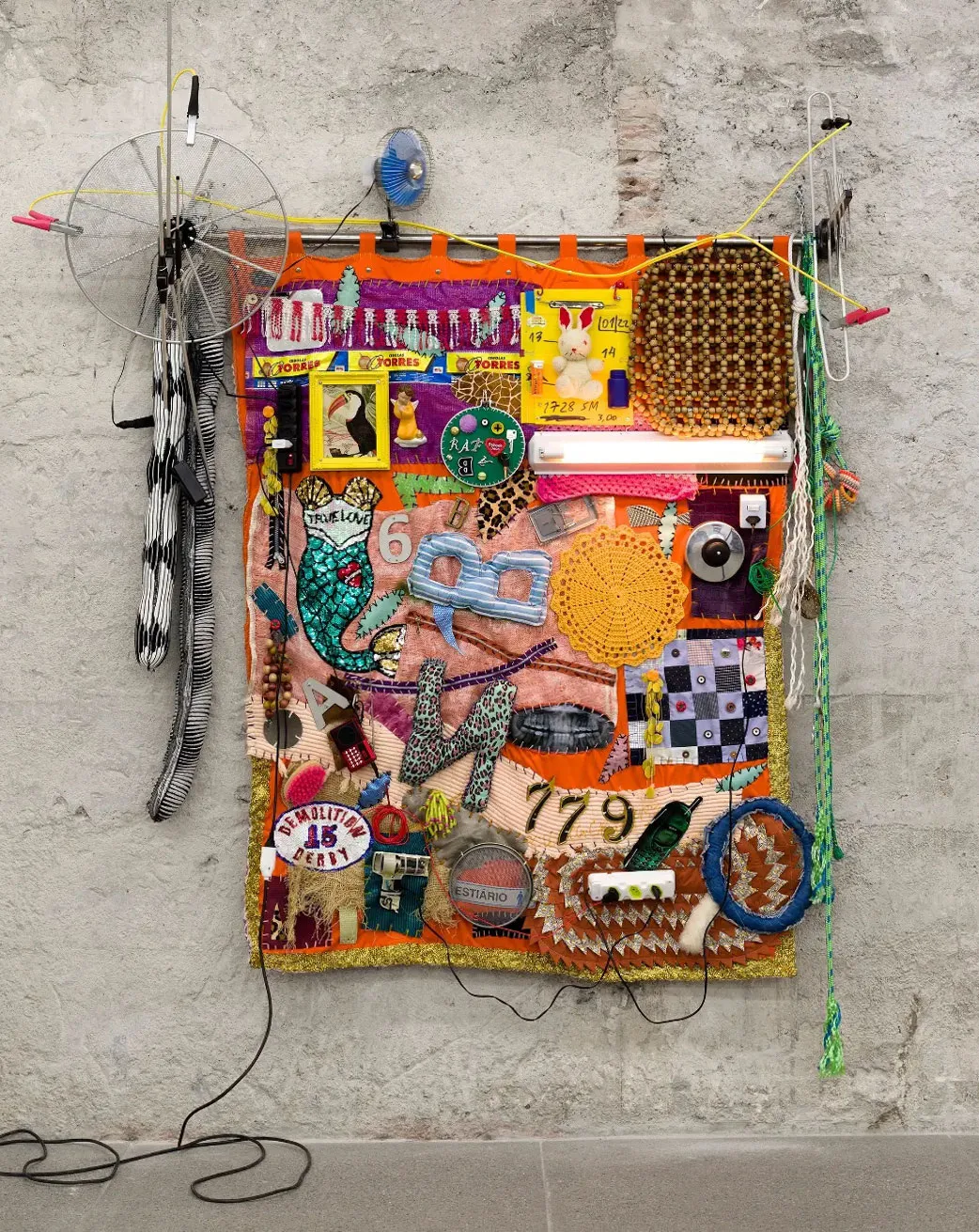

RL: The choice of medium for each project is always a decision that comes from a very intuitive relation between what I want to express and what each material or technique can offer. I move between languages with great fluidity, as this choice happens in a completely spontaneous way, often without rationalizing it. Each medium carries a specificity that resonates with the message or concept of the work, but also with the context it inhabits. For example, sewing and embroidery, which are practices deeply linked to the idea of care, end up being my allies when the theme involves memory, affection, and even everyday violence. These are techniques that speak to repetition and persistence, which, for me, are essential to understand what resistance and survival mean.

I learned to sew by watching my grandmother sew at home, and years later my mother taught me to use the industrial sewing machine, as she worked her whole life as a seamstress in the automotive industry. This practical, familial learning of sewing isn't just a technical skill, it's a heritage rooted in what I do today.

On the other hand, sculpture and installation allow me to create a more physical space, where the presence of the body of the spectator is essential. They help me turn something conceptual into a sensory, concrete experience, and often allow me to create visual and spatial tensions that reinforce the idea of fragmentation and chaos I frequently explore. Photography and collage, for example, come into play when I want to convey a fragment of reality, an image that may be instantaneous, but also carries a sense of deconstruction or multiplicity of layers.

My first training was in the performing arts, and my experience with theater taught me a method of creation that is entirely physical — one that requires a bodily and emotional experience. The body is a central point in all my work, both in the act of creation and in how the spectator interacts with the pieces. Theater taught me the importance of movement, emotion, and presence — elements that remain very much alive in my practice, whether with installation, sculpture or embroidery.

Each technique is a specific vehicle, but what they all have in common is the ability to create a space of ambiguity, where the spectator is invited to fill in the gaps. Using residues from a consumer system that discards everything no longer deemed useful, for instance, is thinking critically of this system. Ultimately, the choice of medium is an extension of what I believe art can do: to be a place of encounter and playful questioning.

JM: Many of your pieces incorporate found materials and repurposed fabrics—objects that carry traces of lived experience. How do you choose these materials, and how does their previous life influence the narratives or themes in your work?

JM: When I first started making art, I worked with discarded and repurposed materials simply because I was broke. I didn't have the money to buy new materials, so I started looking around at what was being thrown away or discarded. What seemed like a limitation ended up being a door to something more interesting. It wasn't just about being cheap, it was about seeing the world differently. Turning what was discarded into something new, giving life to what others saw as worthless, became my language.

Over time, this process of transformation evolved into something else. What started as a necessity became a game, a play with materials, meanings, time. It's like I'm working some kind of spell, where each piece of fabric, every found object, carries the promise of change. It's not magic in some mystical sense, but more like a little enchantment in the way we relate to things in our everyday lives. It's a process full of irony and sarcasm, like I'm playing with the expectations of the audience, challenging the value of things in a rebellious, almost mocking way.

At the same time, this transformation is deeply personal. I learned to sew by watching my grandmother at home, which carries a very emotional quality for me. Thus I'm able to shape memories and feelings that move through me. And it's not just about making things change — it's about connecting with those changes, those layers of time and emotion, in a way that goes beyond creation. That's where the magic of the process comes in. When I work with found materials, what at first glance might seem like trash or something forgotten becomes the starting point for something new, for a new possibility. Every piece, every patch, every stitch, becomes a metaphor for what's possible when we look at the world with a creative, critical eye and, at the same time, with a rebellious, affectionate one.

JM: You often work with textiles, using them as a powerful medium for protest and storytelling. What draws you to textiles as a medium, and how do you view its political potential?

RL: I think a big part of my attraction to textiles comes from the contradictions they carry. Fabric is often tied to intimacy and care. These are materials that evoke comfort, safety, and, in many cases, the quiet monotony of routine. But what happens when you take that same fabric and use it to talk about things that are anything but soft? I intentionally explore that tension between what's supposed to be gentle and what's actually urgent and uncomfortable. In my family's history, textiles symbolized oppression. My mother spent her entire life as a factory worker, sewing on the assembly line for a major car company. It was exhausting, mechanical, repetitive work — completely stripped of personal expression. So when I started working with textiles in art, I found the opposite: autonomy, agency, freedom. Being able to make a living from my artwork now, using that same material, feels almost like a kind of class revenge. It's a way of reclaiming a legacy marked by exploitation and turning it into language, into desire, into creative power.

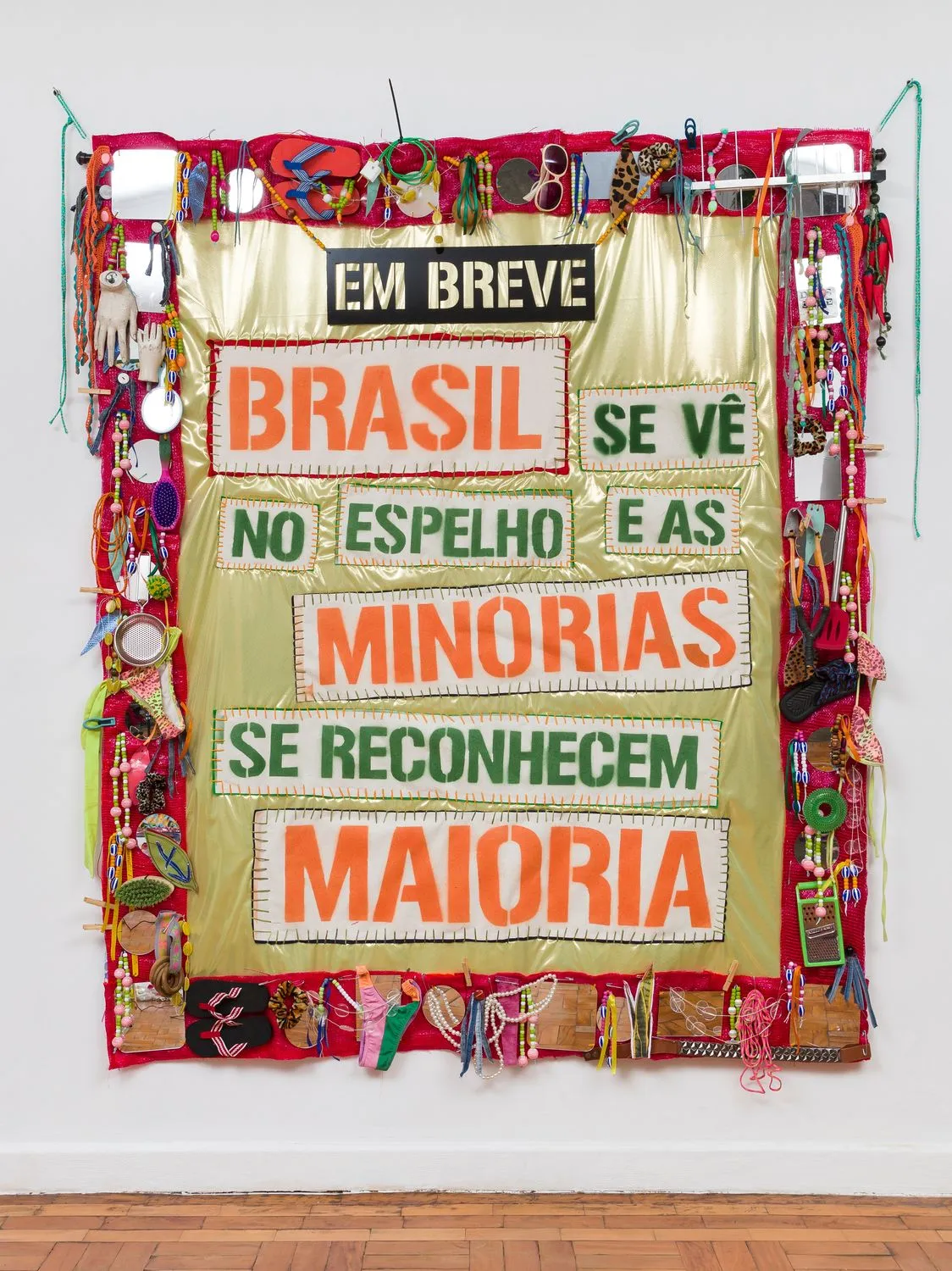

JM: Your pieces often intertwine text with visual elements, creating a dialogue around the themes you explore. How do you approach the relationship between the written word and imagery, and what role does text play in enhancing the political and emotional impact of your art?

RL: For me, words never show up in the work as mere captions. They're matter, body, noise. They fill the space with the same weight as an image or a visual gesture. I treat text as something plastic, but also as a point of friction. Sometimes it creates tension with what's being shown, sometimes it interrupts, sometimes it completes. And often, it produces a kind of short-circuit: the viewer sees one thing, but the word pulls them somewhere else. I love that ambiguity, that back-and-forth between what's seen and what's read.

Text can be direct and accessible, but also poetic, ambiguous, even explosive. I come from a context where language was a tool for survival — something to assert yourself with, or to protect yourself. So there's a political dimension to the way I use language in my work. It becomes a point of connection between the individual and the collective. Sometimes it feels like a public confession, a bathroom note, a piece of graffiti, or a protest chant. It wants to be read, but more than that, it wants to be felt.

And I think we're living in a time flooded with empty words — fake news, hollow speeches, political slogans that never mean what they say. So when I stitch or sew a phrase, or place a sentence at the center of an installation, it's also an attempt to restore some weight, some density to language.

JM: Your work bridges the personal and the public, weaving individual experiences into broader social and cultural contexts. How do you see the relationship between personal memory and collective identity in your practice?

RL: My practice always starts from a personal place. What interests me is how an individual experience — a memory, a trauma, a desire, a shameful experience — can activate questions that are actually shared, that cut across the social and resonate with others. I've been leaning more and more into writing precisely for that reason: because it allows me to access layers I can't always articulate out loud, especially in social or emotional settings. Throughout my life, I've struggled with expressing myself clearly in real time. Writing became a way to compensate for that silence — a space where I could build other ways of enunciation.

Journalling, for instance, has become a really important part of my process. I write almost daily — not necessarily with the intention of sharing it, but to help myself digest the present. These notes, which are sometimes fragile, brutal, or totally unfiltered, end up leaking into the visual work. They show up as fragments, loose phrases, stitched texts, compositions incorporated into materials.

When those words leave the notebook and enter the public space of the artwork, they're no longer fully mine. They start to speak to others, to the world, to the street, to history. That's where personal memory dissolves into the construction of something collective, a shared vulnerability. I don't believe in the separation between the intimate and the political. The intimate is the first frontier of politics. And my work often operates exactly in that seam — sometimes soft, sometimes violent — where private life starts to bleed into the public imagination.

JM: Last year, you've spent time in Belgrade, where you participated in the October Salon and completed a residency at Gallery Hestia, which resulted in your solo show. How did your time there influence the pieces you created, and what did you take away from the experience?

RL: My experience in Belgrade was unexpectedly emotional. I went there by invitation of curators Matthieu Lelièvre — with whom I had previously worked at the 15th Lyon Biennale — and Maja Kolarić, to participate in the October Salon. It was within this context that I also became an artist-in-residence at Gallery Hestia, under the hospitality of Anja Obradović, with the curatorial guidance of Neva Lukić, who has since become a dear friend.

Belgrade has a very particular energy. The city, which has lived through so many historical and political tensions, carries a force that manifests itself in the streets, in its architecture, and in its people. At the same time, what struck me most was a constant presence of time — how it drags on and collides with itself, how the past imposes itself on the present. What I realized was how this tension between what was and what is being lived now resonated in the work I developed.

My practice, which deals with ruins and fragments, ends up directly engaging with this kind of setting. I was already looking in my work for something that played with this notion of time. Belgrade affected me in ways I wasn't expecting. There's this raw, intense energy there that somehow dialogues with what interests me: tensions between past and present, ruins that still live, silent resistances, irony as a language of survival. It's a city marked by layers of conflict, collapse, and reconstruction — which resonates deeply with the logic of the materials I use, the stories I tell, and the way I understand time in my pieces. There's a feeling that everything is always on the verge of breaking, but somehow manages to remain.

JM: Brazil's social and political landscape remains complex and dynamic, navigating significant challenges. How do these realities influence your work, and in what ways do you see your practice responding to or reflecting the current moment in Brazil?

RL: Brazil is a territory of constant contradictions, where the scars of the past never stop bleeding, and the present feels like a daily fight to survive. In every corner, Brazil reinvents itself. This complex, uncomfortable dynamic runs right through me. As an artist, I can't ignore it, I'm part of the social fabric of this country just as much as it's part of me.

My artistic practice feeds on that tension between what is and what should be. From the beginning, I've used art as a kind of mirror — but not a clean or flattering one. It's a distorted mirror that reflects not just beauty, but monstruosity within our society. And that has everything to do with how I see Brazil constantly swinging between collapse and the possibility of something new rising from the ruins. I can't help but reflect the present moment in Brazil — and it's not a comforting reflection. Art has subversive power, and my practice is an attempt to question our history and reflect on how we're living this present.

At the end of the day, I'm just trying to be honest with the moment I'm living in, with the contradictions of the place I come from. If that resonates with what's happening in Brazil today, maybe it's because we're all, in some way, trying to figure out how to move forward in a country that never promised us stability and seems to get worse day by day.

I've been trying to speak about violence without romanticizing it, about resistance without idealizing it, about pain without glorifying it. To me, living in this country means keeping one foot in the fight and the other in hope.