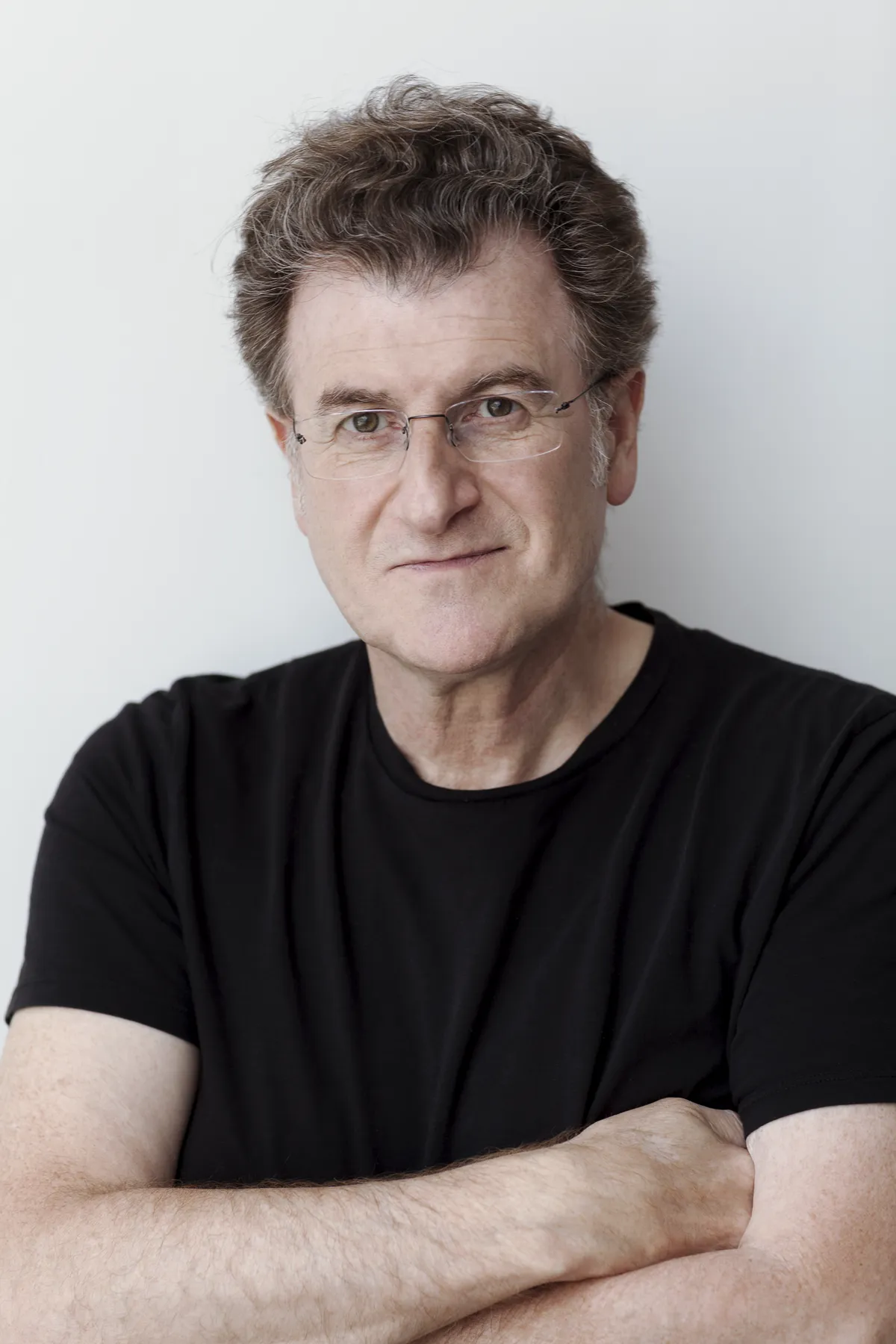

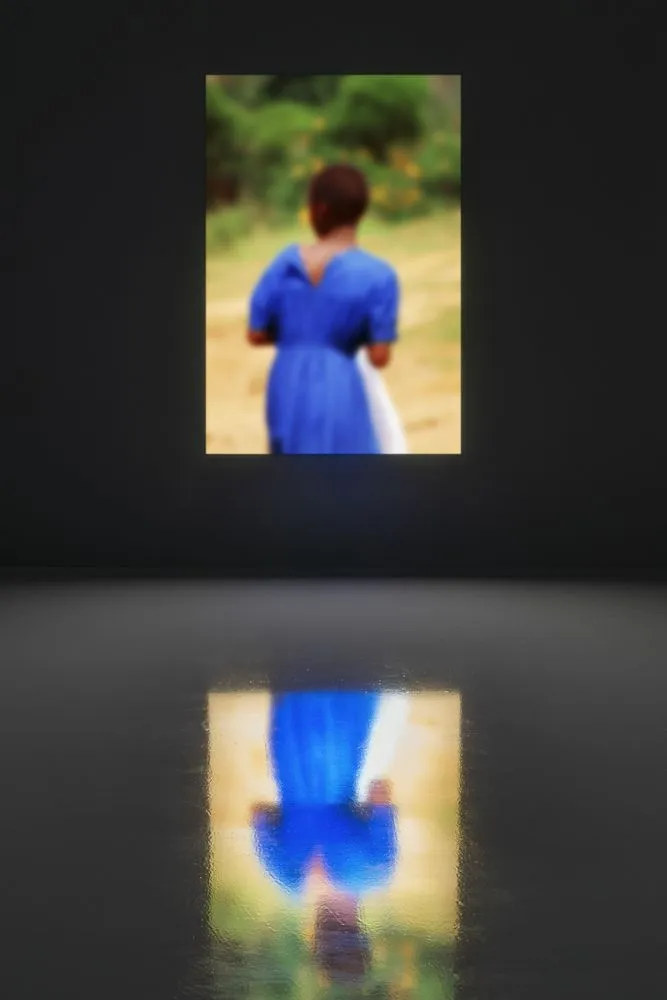

Alfredo Jaar, Six Seconds, 2000, from The Rwanda Project 1994-2010. Courtesy of the artist.

Alfredo Jaar, Six Seconds, 2000, from The Rwanda Project 1994-2010. Courtesy of the artist. One of the most uncompromising and innovative artists of our time, Alfredo Jaar engages deeply with urgent social and political issues often left unseen. Through photography, film, installation, and public interventions, he interrogates systems of oppression, media manipulation, and human rights violations. From his early days in Chile to his global projects today, Jaar seeks to illuminate the overlooked, challenging public awareness and complicity in the world's most pressing crises. Whether addressing the violence of war, environmental destruction, or the complexities of migration, his work unveils uncomfortable truths that disrupt mainstream narratives, questioning how history is written and who controls the power to define it.

Born in Santiago, Chile, during Pinochet's brutal dictatorship, Jaar's early experiences with censorship and repression profoundly shaped both his worldview and his artistic practice. Living through these turbulent years, he learned to navigate the stifling environment and find ways to make his voice heard, realizing the importance of art as a tool for resistance. Jaar credits his studies in architecture with providing him both the freedom and a unique perspective in approaching his projects. It instilled in him the importance of understanding the world before acting in it—an approach that continues to guide his work today.

Engaging on a deep level, Jaar critically examines how knowledge is constructed, exploring the mechanisms that shape our understanding and relationship with the world. Addressing the horrors of our age, Jaar highlights the complexity of representation, reminding us that true understanding requires an active, critical, and often uncomfortable engagement with the world. His projects are rooted in a meticulous process of research and immersion, from his time spent documenting the tragic consequences of mining in Brazil to his six-year long exploration of the aftermath of the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

I had the pleasure of sitting down with Alfredo Jaar in Belgrade, where he hosted a lecture as part of the 60th October Salon. In our conversation, Jaar discusses the intellectual and emotional currents that drive his practice and the ethical frameworks shaping his work. He delves into his meticulous research process, the politics of representation, and his sensitive approach to memory and trauma, acknowledging the ethical responsibilities artists bear when representing such experiences. Jaar also reflects on the role of media in shaping public perception, highlighting how narratives are selectively constructed and how certain crises are rendered invisible. Finally, he shares why he is a pessimist by intellect but an optimist by will—a paradox that fuels his enduring belief in the power of art to provoke change, even in the most challenging circumstances.

Jelena Martinovic: I would like to go back to your upbringing in Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship. How has this experience influenced your artistic practice and your approach to engaging with the world?

Alfredo Jaar: The experience of the dictatorship was brutal. It changed me and my entire generation. For example, the first thing the military did was forbid reunions and any kind of meetings. They considered gatherings of more than three people as subversive, so we couldn't do it. My generation didn't have parties. Can you imagine what that is? That's just the tip of the iceberg. Yes, life under the dictatorship is brutal and changes everything.

I wanted to be an artist, and I started making art early on. In the scene, two schools of thought developed. One said we should not make art at all—no exhibitions, no writing, no music—because doing so would normalize the dictatorship, as if everything was okay. The other school of thought was exactly the opposite. It asserted that we had to create as much as we could. We knew there was censorship and a red line, but we had to find ways to make our voices heard. We weren't alone; the majority of Chileans wanted to return to democracy, and we had to signal to the world that we were alive and resisting.

For one reason or another, I aligned with the second group and began acting as an artist during the dictatorship, navigating the censorship. If there's something worse than censorship, it's self-censorship because of fear. Each artist created their own red line. I had mine, and before publicly releasing any project, I would analyze it, asking myself: Is this okay? Could this mean trouble? Will I be arrested? Will I disappear?

This was the time of the disappearances—los desaparecidos—a term for people who were basically killed. You start learning how to function in a repressive environment, how to speak between the lines, and how to navigate challenges. Some of us were more courageous than others; some kept their red lines tight, while others ventured further. We were gambling on our assessments of where those red lines were, but that's how we functioned.

JM: However, your educational background is in architecture, and you've mentioned in your lecture that not having formal art education gives you freedom in your work. Could you tell us more about this unique vantage point?

AJ: Yes, I consider myself extremely lucky. I wanted to be an artist, but my father, rightly so in Chile in the 70s, thought that was a bad idea. He convinced me to study architecture. At 17, I thought he was probably right, so I went into architecture. Very soon after starting my studies, I realized I was the happiest man on earth. I discovered that architecture would give me the tools to create not just architecture but something else.

Much later, I realized that not studying art—meaning not being taught how to use one particular medium, but rather how to think—was the best tool I could have been given. That's why, when I teach, I tell my students that for me, art is 99% thinking and 1% making. When teaching seminars or workshops, I often go against the grain. Schools tend to push students to produce things, as if making things will develop their thinking. I believe it's better to stop making stuff altogether. My first declaration is: please stop making things. Let's start talking and thinking, and then, eventually, we can create something at the end of the process.

In my architecture studies, I discovered many aspects of architectural methodology. Because I hadn't studied art, I naturally started applying the same methodology to art-making, and I found this to be a valuable tool. I learned that context is everything. You must respond to a specific context, and to do that, you must understand it. In my case, the context was living in a military dictatorship. So, what could be done within that context? All the art I made responded to that particular situation. I've always defined myself as a project artist, not a studio artist. In this case, more than ever, you couldn't just go to a studio, create, and throw it out into the world. You had to think about the context and what could be done within it.

JM: This personal manifesto of yours emphasizes understanding the world before acting in it. Why do you believe this approach is essential for your artistic practice and how does it guide your artistic process?

AJ: I am a maximalist in that sense. I feel it is utterly irresponsible to create something and present it to an audience without knowing who they are, what language they speak, and what situation they find themselves in. It doesn't make sense. This relates to my Cartesian education; I was taught to make sense of things.

For an architect to design any space without knowing its use—who will use it, where the sun comes from, where the wind blows, the scale of the space, and what's across the street—is unthinkable. You cannot do anything without understanding these factors. Therefore, it seemed logical to adapt these same rules to making art. This mindset has saved me; since I didn't have an art education, I had to grab onto something, and what I seized was my architecture studies.

JM: Your work addresses some of the darkest horrors of our age. Given the overwhelming amount of injustice in the world, how do you choose which subjects to engage with in your art?

AJ: My father was a news junkie. He couldn't leave home without reading two or three newspapers. From a young age, I observed him reading his papers every day religiously before leaving the house. In the evening, he would bring the afternoon papers and read them again. Our conversations during lunch and dinner always revolved around current events, both in our immediate world and globally.

I grew up in that environment, and naturally, I began reading the news too. I learned several languages from my life experiences, which allowed me to read in different languages. First it was the physical paper, and now it is through the internet. I start my day by spending two hours each morning at breakfast, reading the news in various languages and from different media outlets and different parts of the world. Like my father, I need to understand what’s happening around me—not just my immediate surroundings but the wider world.

I follow many events, archiving information. Currently, there are about 37 conflicts around the world that I'm tracking, sometimes for weeks or years. I read about them and am interested in seeing how different points of view describe certain situations. I note the biases and various ways that media outlets report these events.

I accumulate this information, and then suddenly something happens—like the Rwandan genocide. I had been following developments in Rwanda for many years, aware that something was brewing. It all began on April 6th, 1994, when the genocide erupted. By May, I was shocked and filled with rage at the world's barbaric indifference. A million people had been killed in just 100 days, and nobody cared. Efforts were made to suppress the term "genocide" because if you accept that it's a genocide, the UN Convention compels you to act.

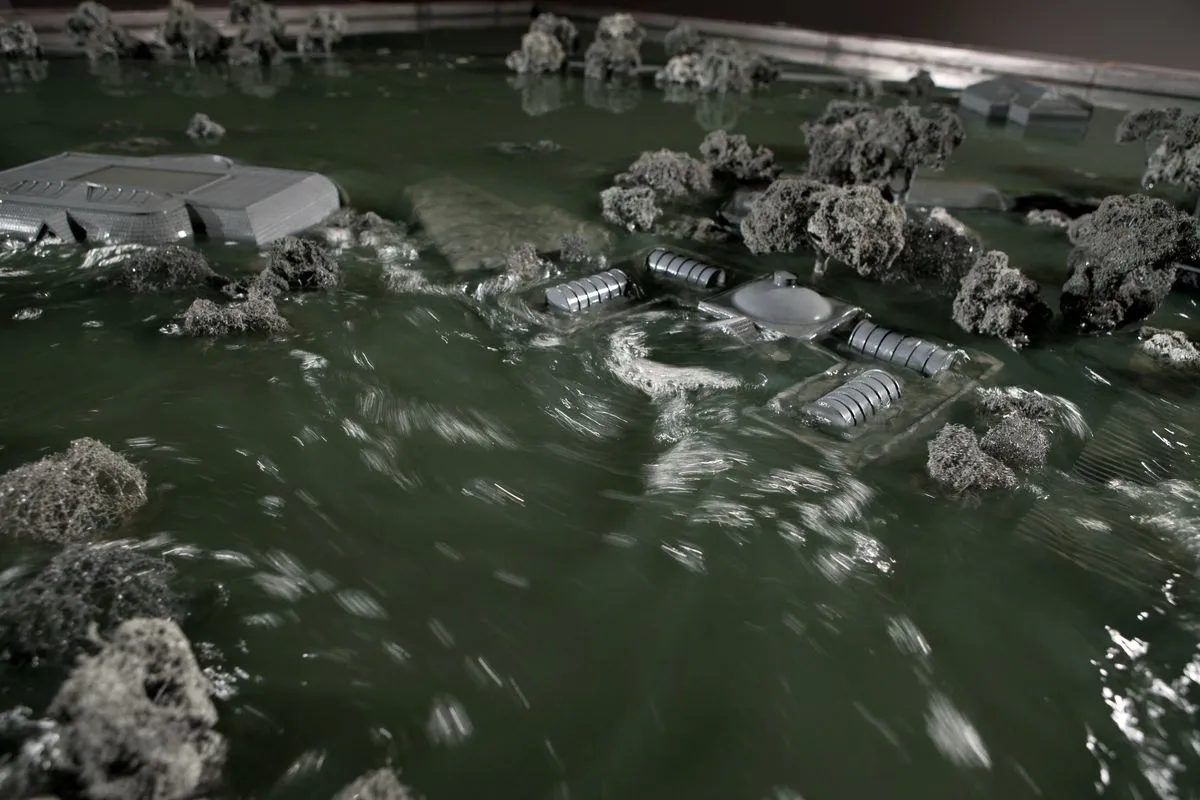

When I realized this, I thought, “This cannot continue.” I made a bold decision—I went to Rwanda. This triggered the Rwanda project, which led to six years of work on it, including 25 different projects. It's that moment of either rage or illumination—something that compels me to say, “I cannot take this. I have to address it.” That's what typically triggers my projects.

JM: A significant aspect of your project on the Rwandan genocide focuses on the failures of media coverage and the international response. How does this lens inform your understanding of contemporary media narratives surrounding current conflicts?

AJ: I learned a lot from that experience, and similar patterns are evident in current conflicts. One of my early critiques involved the media's coverage of the Ukraine invasion by Russia. I created a piece titled Mea Culpa in response to a striking cover of The Economist that depicted the Ukrainian flag with a drop of blood. I was shocked and impressed. It was unprecedented for the magazine, which typically focuses on financial matters, to dedicate so much coverage to the Ukraine conflict. However, I noted a lack of attention to other conflicts with even greater historical significance and casualties. For my project Mea Culpa, I mimicked that cover for Iraq, Syria, Burma, Ethiopia, Sudan, Palestine, and many other countries. I've sent these to The Economist, congratulating them on the Ukraine cover while highlighting that they forgot to cover these other conflicts. Although they ignored me, it was a gesture of my own therapy.

The Ukraine conflict receives prominent coverage due to its strategic significance for the West, which frames Russia as the enemy attacking a European nation. This focus renders other conflicts, where Western nations are often the aggressors, largely invisible. The media's treatment of the Ukraine crisis diverts attention from pressing issues, reflecting a biased narrative. It’s crucial to address the situation in Ukraine; it is indeed a serious conflict marked by Russian aggression. While I do not defend Russia, the prioritization of this conflict in the media stems from a desire to criticize and attack Putin. The actions of NATO and the United States seem aimed at weakening him, despite my belief that this aggression is a result of provocation from the U.S.

The situation in Gaza presents a different historical context. The West tends to adopt the perspective of the aggressor rather than that of the victims, given its alignment with the aggressor. This reflects a reversal of the media's treatment of the Ukraine conflict, where established norms in democratic societies are disregarded in the context of Palestine. The aggressor has caused the deaths of approximately 100,000 people and destroyed housing for 2.4 million. That is the reality in Gaza today.

The October 7th was a tremendous tragedy and a war crime by Hamas, but it is also a response to the long-standing situation prior to that date. However, it's evident that Western media conveniently starts the narrative from October 7th, ignoring the historical context. Consequently, the aggressor is portrayed as the good guy while the victim becomes the villain. I find the behavior of Western media appalling; their docility is shocking and undermines their credibility. On the other hand, Israel has not allowed journalists to go into Gaza because they don't want the world to see what's happening there. They have also killed more than 150 journalists. That's another obscene fact. However, what is more obscene is how Western journalists have ignored this fact. They have not protested nor collectively made declarations against this blackout.

Today, the world appears sharply divided: on one side we have a small fraction of Western countries, making up about 12% of the global population, and on the other side we have 88% of the rest of the world which are against this aggression. This 12% of the population primarily consumes media from outlets like the BBC and CNN, while the remaining 88% engages with perspectives from networks such as Al Jazeera. This polarization of narratives raises pressing concerns about how we reconcile these two divergent realities. At some point, these two worlds must meet; otherwise, it raises questions about what comes next.

JM: You've also said that your work can be divided before and after Rwanda and that the experience of working on this project has significantly changed your relationship with images. How do you see the power of images today and the way we engage with them?

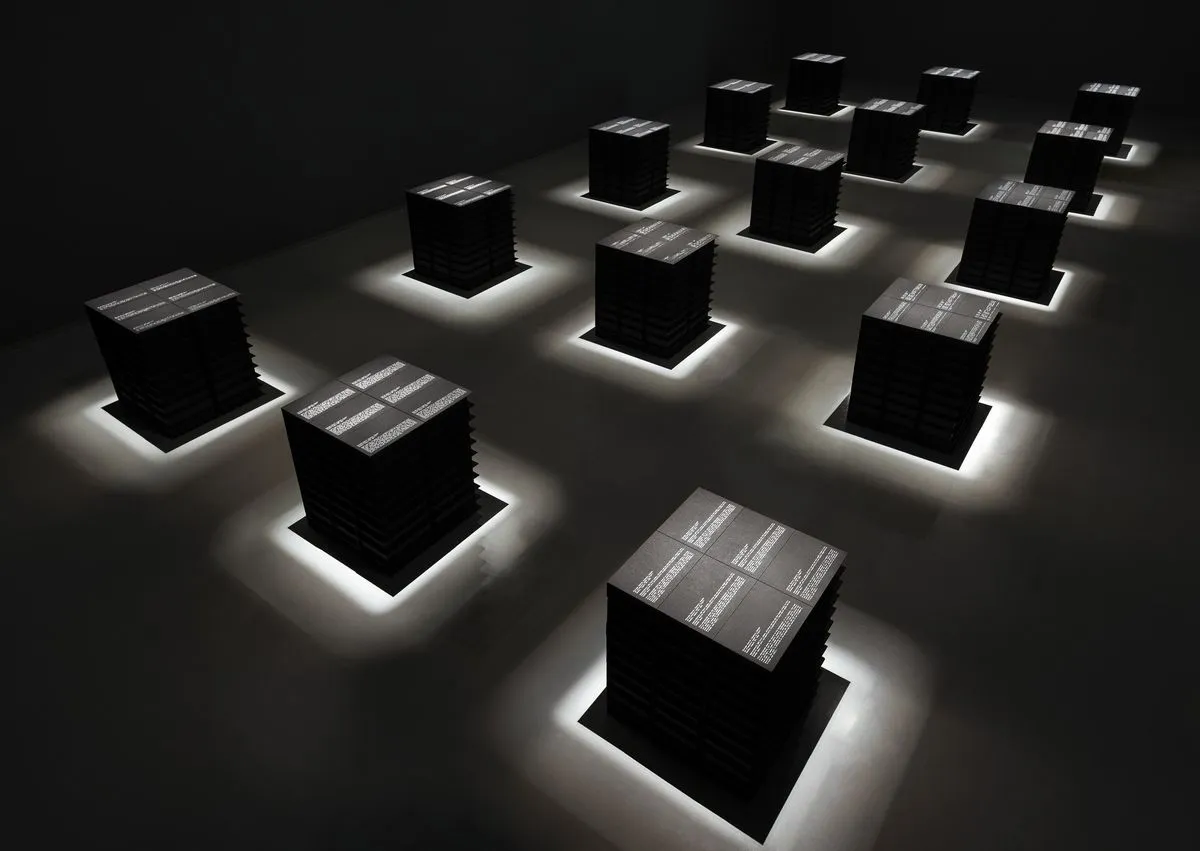

AJ: Before my experiences in Rwanda, I used images freely in my work, either mine or appropriated, always as part of larger installations. However, Rwanda fundamentally changed my perspective on photography. I became much more critical of how images are used and understood, and I've drastically reduced the number of images I display. From the Rwandan project itself, I only showcased about ten of the 3,177 images I captured. I became much more critical of how I perceive images, how they are used, and how an image carries memory. I also reflect on how that memory can be affected by my engagement with the work as an audience. This shift has led me to focus on the "politics of images," where I use them more selectively and with an emphasis on context and meaning.

JM: Memory plays a crucial role in many of your projects. How do you approach the act of remembering in your work?

AJ: My approach to memory varies with each project. For each project, I must consider what memory means for me, my audience, and the individuals I am representing. This is complex, and I continue to learn as I go. It is a very complex issue, and I've been learning through my work. I'm not a specialist in historical remembrance, but I've discovered the power of memory and how it shapes our thoughts, perceptions, and actions in the world. This is something to respect when meeting people from unfamiliar places. Listening to their experiences is crucial because their life stories dictate how they think and speak. You have to learn to translate those real-life experiences into visual products in a careful and respectful way. These memories are not ours to appropriate. It's a delicate subject, and I often ask myself if I'm doing it right or if there's something I could do better. However, I have learned along the way.

JM: All of the subjects that you engage with are very sensitive. How do you navigate the ethical considerations of representing a sensitive subject in your art without exploiting it?

AJ: On one level, as an artist, intellectual, or activist, I must decide: should I condemn this situation to invisibility, or should I try to make it visible? Should I accept the mistakes I might make in this process, knowing that at least I will bring attention to an issue, or should I simply say, "No, you do not belong here; ignore it?" What is the price I will pay for attempting to illuminate this unbearable reality that no one wants to see? Is that price acceptable to me? Can I bear that cost? My answer has always been yes—do it.

I've embraced a concept from East German writer Heiner Müller, who wrote a book called Chosen Mistakes. In every work where I engage with someone else, it becomes a chosen mistake. While it may be a mistake, I have intentionally made it, understanding that it will have consequences. Some may criticize me, but I would rather bear that criticism than allow silence to prevail. In exchange, I've brought visibility to something I believe deserves it. That is my first moral stance.

The second point is that when working with people from different cultures, languages, religions, and races, you can never truly speak for them. During my Rwandan project, I never became a Rwandan artist or citizen; I was always speaking from my own perspective. When I critiqued the Western media, for example, I was doing so as someone who engages with that media and questions how it can ignore certain realities. I am not speaking for Rwanda; I am always speaking for myself. This is not a paternalistic viewpoint; rather, it is a critical perspective grounded in my own experience.

Combining this awareness with sensitivity to the reality I am addressing is crucial. As I mentioned in my lecture yesterday, I believe it is fundamental to understand before taking action. My work results from countless hours, days, and weeks—sometimes months—of trying to comprehend the context. Who am I to enter Kigali, Rwanda, and comment on the genocide without fully understanding it? That would be obscene, a significant mistake, and an irresponsible act. Therefore, I hold myself to the standard of needing to understand and to prepare thoroughly before I act.

Additionally, when addressing other cultures or experiences, I avoid speaking for others. During my Rwandan project, I always presented my perspective rather than assuming the voice of a Rwandan. My critiques of Western media, for example, come from my standpoint as a consumer of that media, questioning its neglect of critical realities. Thus, I strive to be sensitive and informed before taking action. Understanding the context of a situation is essential; I believe that to comment on a tragedy, one must first engage deeply with its historical and cultural dimensions.

JM: Given the diversity of your work in terms of media and style, how do you navigate these different projects? Specifically, how do you decide which media to use when approaching a subject?

AJ: I've always felt that the idea tells me what to do; I let the idea decide. I do an enormous amount of research, and when I feel I've learned enough—what I call "responsible knowledge"—I try to act. When I'm ready to act, I come up with ideas, and these ideas are the result of all that research. It's only at that moment that I discover the best way to articulate the ideas. That's when creativity plays a role: I decide, for example, this idea is best articulated with water, this one with light, and this one with writing. I'm no specialist in water, light, or writing, but it doesn't matter because I work with ideas. The beauty of this process is that the idea needs articulation, and I find the right people, specialists, and collaborators who help me physically bring the idea into the world.

That's why, when people look at the works I've done over the last ten, twenty, or thirty years, they might think it's a different artist. I don't have a trademark, and that's a sign of my freedom. I don't care—I don't need a trademark. I don't need to go through a “blue period” like Picasso, spending years on one thing. I work with ideas, not canvas and color.

JM: I'd like to revisit your participation in the Venice Biennale in 1986, where you became the first artist from Latin America to take part. What did this experience mean to you at that stage of your career?

AJ: When I started in the early 80s, the world wasn't as global as it is today. It was almost impossible to find artists from Latin America, Asia, Africa, or Eastern Europe in museums or galleries in New York or Europe. It just didn't happen. That was part of our discussion as artists: How are we going to penetrate this impossible space?

I moved to New York in 1982 and worked as an architect for five years, but I wanted to be an artist there. So, as an architect would do, I thought, okay, I need to understand the art world first. I became a cultural anthropologist, going to every exhibition, subscribing to art magazines, attending lectures, and immersing myself in the art world to understand how it worked. After a few years, I thought, now I understand. The first realization was that New York was the center of the art world at the time—today, it's not the case, as there are many center across the globe. However, at the time, it was fascinating, full of extraordinary exhibitions and artists, though without any representation from what we now call the Global South.

The second realization, and a more crucial one, was that New York was provincial. When they spoke about international exhibitions, it meant a few Germans and Americans. The work was only about themselves. The world didn’t exist in the museums or galleries. So, I gave myself a program: I was going to bring the world to this place.

In 1984, I came across a six-line story in a French paper about a gold mine in Brazil where 100,000 men were digging with their hands—no machines. It was like Dante's hell. I got a grant and documented the miners, the work, and the human cost of this highly exploitative work. Then I thought, how do I show this reality in New York, this place of luxury? Where is gold in New York? It's in Wall Street. They are working on their computers, dealing, selling, and buying gold like any other mineral, like any other financial asset. I wanted to show them the reality of mining gold. I got another grant and rented a subway station where brokers would see these images of gold mines alongside the current price of gold in world markets. That was my first intervention. It was called Rushes, and it put me on the map of the art world, reaching the Venice Biennale in 1986.

JM: Forty years later, how do you view the ongoing challenges regarding accessibility and representation within the global art world today?

AJ: It's much, much better, but there's still so much to do. We haven't reached a level of equality, and I'm not sure we ever will because there haven't been truly structural changes. Some enlightened curators and intellectuals have realized they need to open up and invite artists from outside the center, and now you see strong representation from Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

That's a huge difference from the 80s because we now serve as models for young artists from those places. They see that if we made it, they can too. That's incredibly powerful. But it's not enough. We still need to fight for visibility, and while the process has started, the center cannot hold forever. I just don't know what it will take to reach a point of true justice and democracy in the art world.

JM: What do you believe is the role of art and artists in addressing these systemic injustices and entrenched power structures?

AJ: In my case, as soon as I reached a position of influence—not power, but influence—I realized I could make changes in my small world. For example, 25 years ago, I was invited to exhibit in Japan. It was my first time there and it was a very exciting prospect for me to exhibit there. However, while being at the gallery, I noticed that it only represented one woman out of many male artists. I told the dealer that while I was honored to exhibit, I wouldn't continue working with them unless they improved that ratio. I still remember the smile on his face, he thought I was crazy. (laughs) However, today the gallery represents almost more women than men and this is the reason I stayed with them. It was a small, private act of solidarity, but these little things matter.

JM: During your lecture, you've referenced Chinua Achebe's definition of art as a man's constant effort to change the order of reality. Given that this ongoing endeavor often doesn't yield immediate or tangible results, how do you navigate the emotional weight of engaging with these subjects, and what drives you to persist in this work?

AJ: Well, of course, I haven't changed any order of reality, but I keep trying. (laughs) I need to quote Gramsci, who wrote his most important essays from prison. In one of these essays, he described himself as a pessimist by intellect but an optimist by will. I was very young when I read that, and I immediately thought it was a kind of mantra. What he was trying to say was that, intellectually, he was pessimistic, looking at the state of the world while being imprisoned by Mussolini. But you either give up and commit suicide or act with your will. If your will is optimistic, it drives you to act, even in a pessimistic world. You try to find the light, although it's difficult. I haven't found it yet, and I don't expect to—but it's either that or killing myself.