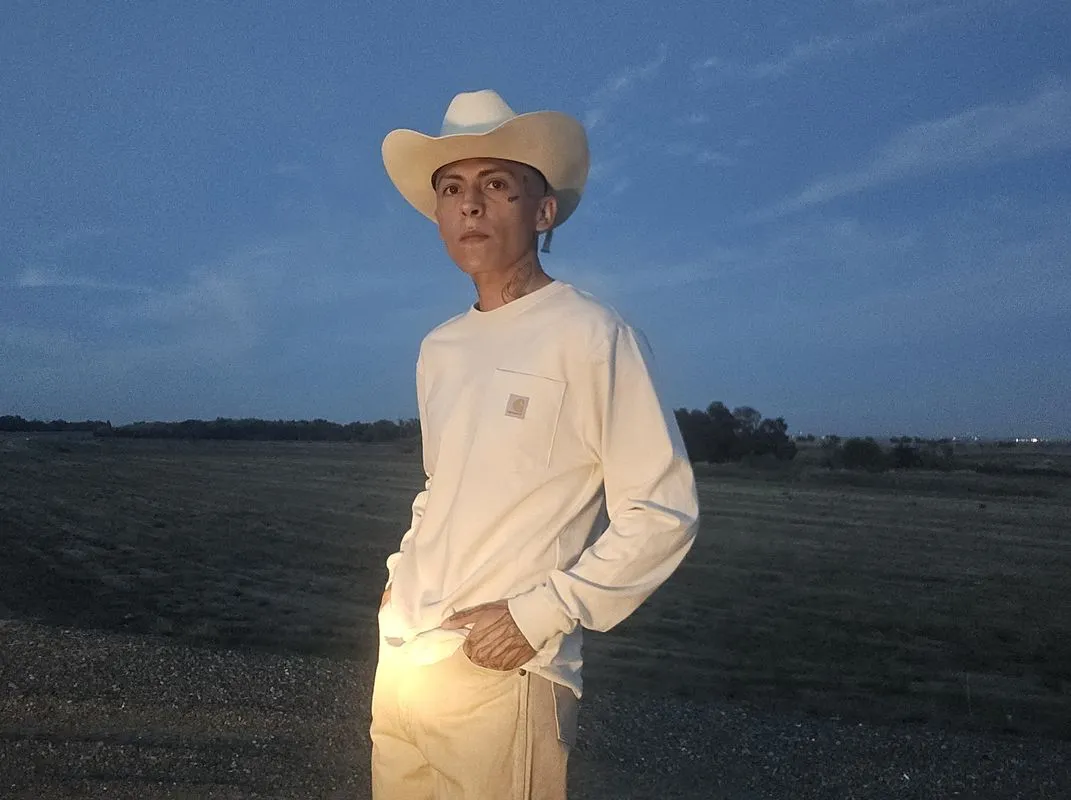

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Oriana. Film still from Photo by Sara Griffith from Oriana by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Oriana. Film still from Photo by Sara Griffith from Oriana by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz Based in Glasgow, the political arts organisation Arika has carved out a distinctive space where art intersects with social consciousness, fostering dialogues that challenge the status quo. Their ethos revolves around the belief that art can catalyze social change, bridging the gap between critical thought and political activism. By organizing collaborative projects that gather artists, activists, educators, and communities, Arika creates a platform for voices often marginalized in mainstream discourse. Each program invites participants to reimagine coexistence and explore alternative futures through the lens of creativity. In recognition of their groundbreaking work, Arika was awarded the Turner Prize Bursary in 2020, underscoring their influence and innovation in the arts.

As they prepare for Episode 11: To End The World As We Know It, running from November 13 to 17 at Tramway, Arika continues this vital work. This ambitious five-day event will feature an eclectic mix of performances, discussions, and screenings that delve into pressing ecological and social issues. With contributions from renowned figures like Ailton Krenak, Denise Ferreira da Silva, and the Karrabing Film Collective, Episode 11 promises to ignite discussions about the world’s future and our role within it.

"What if we took seriously the possibility that this world, as we know it, may be coming to an end? What if we considered that this may well result from both ecological and social devastations as well as radical propositions and programs for another world, a better world, whatever that may look like? We dread the loss of this world, but have we begun to imagine the one to come? How to imagine it collaboratively?" - Denise Ferreira da Silva, participating at the Episode.

Through thought-provoking sessions such as For Ever Gaza by Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri and Against a monoculture of thought by Geni Núñez, to name a few, participants will engage with radical propositions for reimagining community and solidarity in the face of imminent change. As the world grapples with multiple crises, this Episode encourages us to confront our fears and imagine collaboratively the possibilities that lie ahead. In this interview with Barry Esson, we explore Arika’s journey, the ethos behind Episode 11, and how they inspire collective imagination to envision a better world.

Jelena Martinovic: Arika has been bridging the gap between art and activism for the past twenty years, creating spaces for dialogue around pressing social issues. How has the organization evolved during this time, and what key moments or experiences have been particularly influential in shaping your mission and direction?

Barry Esson: We started out organising experimental music and experimental film festivals. Those went really well. I think two or three key encounters changed our direction, led us to stop doing those festivals and start Episodes, Local Organising and other projects like those, which perhaps look more orientated towards social justice.

Working with the communist sound art collective Ultra-Red, starting around 2009, helped us learn about the social efficacy of paying attention to listening, who gets to speak, what they have to say, and how we listen to political struggle.

Working with the noise musician Mattin, between 2010-2012, helped us think about the problem of the self from a speculative, Marxist perspective, and the potential of noise to disrupt that more fixed self.

Working with Fred Moten, from 2012 onwards, opened us out to this incredibly rich, varied and evolving engagement with fugitivity, refusal, the Black Radical Tradition, anti-colonialism, and a critique of individuation and ontology.

Working with Tina Zavitsanos, Park MacArthur, and others in the realm of disability justice and crip aesthetics introduced us to an expanded understanding of access, intimacy, and dependency.

Working with Luca Stevenson, who established the Sex Workers Open University (now the Sex Workers Advocacy and Resistance Movement, or SWARM), allowed us to explore the aesthetic dimensions of movement building, anti-stigma organizing, abolition, and prefigurative world-building.

And lots of others, to be honest… all the time and ongoing!

JM: Arika seems to push the boundaries of what is typically understood as 'art.' How do you define art in the context of your work, and how does this expanded notion influence your efforts to foster deeper social and political engagement?

BE: I think we try and engage in what might be called the aesthetic registers of sociality, thinking we take from Black Studies collaborators like Fred Moten and Laura Harris. How we understand that is a belief in the artistic and ethical potential of paying close attention to how we move and want to be moved, look and want to be seen, feel and want to be felt, listen and want to be heard.

Which is to say that aesthetics, critical thought and social organizing commingle, or indeed are just at some point different perspectives on the same thing; aspects of our sociality, needs, desires and struggles.

Often we are encouraged to think that change comes about through ‘engagement’, or even through politics. I think we should be wary of such terms. Maybe this comes up in your next question too, in terms of inclusion, so I can say more about that there. In terms of politics, I feel like maybe we tend to think more in terms of the social, or sociality. The realm of politics, based on a polis to which only certain people are admitted, seems like a dead end, based around some kind of inside-outside binary.

As opposed to opposition, we like to think of apposition—of being off to the side, rather than outside. Fred Moten calls this being ‘out from the outside’. I feel like we are more drawn to practices that seek to make and remake the world anew for themselves and are focused on their own practices, even while under duress and exposed to total violence, a practice that is both more and less than the limited notion of politics, and maybe closer to what many of our friends and collaborators would think of as refusal and abolition.

JM: You are committed to working with traditionally marginalized communities. How do you address the complexities of inclusion and representation in the arts to ensure that these communities are not only visible but also involved in shaping their own narratives?

BE: We don’t think that the liberal notion of inclusion accomplishes much really. The great anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli, who is participating in the Episode, says that "The cunning of post-war liberalism was to treat legitimate critiques of colonial capitalism as if they were a desire to be recognized by the dominant state and its normative powers: that what the oppressed want more than survival is recognition from the oppressor." This predatory, burdenous, and onerous inclusion is always contingent, and comes at a cost. Ariella Azoulay calls that kind of inclusion ‘incorporative exclusion’.

At the same time, we have decided that in order to do some of the things we want to do, we will apply for public funding—that funding is in some respects predicated on the forms of inclusion Povinelli or Azoulay criticize. So we have a contradiction to work through.

How do we access resources, which are ours anyway, to further our and our allies aims, while not contributing to the ways those funds are meant to administer inclusion and representation? We try to do this in a few ways, with I guess varying degrees of ‘success’.

One example might be the way we set aside a significant part of our resources for what we call ‘local organising’, where grassroots communities we are entangled with (in the migrant process, in sex worker organising, in rent struggles, in VAWG settings), and work with them so that they have the agency to decide how to use those resources on things they want or need.

That way resources—money, staff support, access to things—gets redistributed in some sense. We try to convince our funders of the value of this, while withholding from those funders the information and data that they might want to extract from those groups about what they do, how they do it, who is involved or whatever—these activities might not appear on our website, and not directly reported on to funders. I don’t know if this is the best way to approach it, but it’s one way we try to stay within and manoeuvre through the contradictions of our situation.

JM: Arika’s projects are described as 'Episodes,' which suggests an ongoing narrative or unfolding process. How did this episodic approach come about, and what does it allow you to do that a more traditional arts program structure might not?

BE: Yeah, that’s cool that the notion of there being a narrative comes across!

We think the Episodes are one long, ongoing deconstructed festival, with a narrative that develops over time. So what happens at one Episode might seed some things that come to fruition at another one further down the line, even if in unpredictable ways. We don’t know what future episodes are going to be about, but there are themes and concerns underneath them, that show up in different non-liner ways, depending on the circumstances, what’s going on at the time—socially, politically, in the wider world and also in the relationships we have with artists, communities, philosophers, activist and so on. We also try to work through friendship and solidarity, that means that we want to work with people in a sustained way, over time, so that our relationships deepen and we can try and create more meaningful events. You can see this in this Episode with people like Denise Ferreira da Silva, whom we’ve worked with since 2014, or Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri, returning for the first time since Episode 1 in 2012, as well as in events that have taken a long time to come to fruition, like those involving Leanne Betasamosake Simpson or Karrabing, with whom we began discussions before the pandemic.

So the point, or perhaps the organizing principle, is to be led by what happens and focus on deepening thinking and relationships over time. We’re not a festival trying to identify what is cool at any given moment or following trends—although I suppose we do that too, but it’s not so intentional! Instead, we’re working together through common concerns and ideas, which might mean looping back, moving forward, or going off on tangents. And I guess we think of that as narrative, in just quite a basic way, and in the same way that the narrative of a novel, or a tv show might have things that happen in one chapter or episode that inform what happens in future ones. That narrative gets coalesced into a theme for an episode— set of questions or proposals, around which to organise speculative aesthetic social encounters. The proposal this time is: can we imagine the world to come, in which we know that world in ways different to the dominant ways of knowing now?

JM: The title of your upcoming Episode, To End the World As We Know It, evokes a sense of urgency and transformation. What inspired you to choose this theme, and how does it resonate with the current state of the world?

BE: Well, it comes from Denise Ferreira da Silva’s thinking, really. Here’s a WhatsApp message she sent to a group we have with her, that sets it out:

"Here are some of the things in regard to the phrase “the end of the world as we know it”: it is about the end of the known world, the world state: capital in all its apparitions and the modes of knowing (scientific and historical) that support its colonial (extractive, expropriative, genocidal) practices and propositions and promises (of development, of freedom, etc, which are all contingent on total violence)."

That means that other ways of knowing, existing, and conceiving existence—of both human and nonhuman—must be imagined, experimented with, and supported by any means necessary.

The end of the world as we know it would bring the end of ‘world’ itself, and with that, the end of phenomenology and the subjectivity it consolidates, which defines itself in/as knowledge. To end the world as we know it is to exist otherwise, right here and right now.

What we take from it is that there are other ways to know and be in the world and that the ways that have dominated how we come to know the world are Eurocentric fictions that have been retrospectively invented to justify colonial violence. It's important that we study these fictions—property, whiteness, extraction, the human, etc—and also practice other ways of being, or engage with people who already do.

JM: Your program brings together a wide range of voices—artists, activists, musicians, poets, and more—while collaboration seems central to your approach. Could you describe how you curate the program and select participants, and how this collaborative spirit manifests in both your current Episode and your ongoing partnerships?

BE: We try to move through friendship and solidarity. We work with some people we think are exceptional, and if that goes well, they introduce us to other people, and if we get on, we work with them too, and so on. It’s not very predictable. At the same time, we want our work to engage with many different perspectives, and in doing so build up a better picture of what’s going on and how people organise and practice, in ways that don’t get limited to any one perspective (geography, identity, etc). So we’re trying to look at all the relationships we have, and then put them in relationships also, which create tension and haptics as things rub up against each other, and that’s super interesting.

Also, I guess, we have to look at what is happening around us, and maybe address gaps or lacks in past programmes. So it's been obvious this time that while it's been there for a long time in different projects, right now we much more explicitly need to address settler colonialism, and frame our critiques of this dominant way of knowing the world in relation to that.

These relationships sometimes lead to other projects, like I wanna be with you everywhere, or emerge from other projects first, like Local Organising.

JM: Beyond the current Episode, what other projects or initiatives is Arika working on, and how do they reflect your evolving approach to art and activism?

BE: It's pretty hard to know really, given what is happening with arts funding in Scotland at the moment. No one can plan beyond March 2025.

Having said that, we’re involved with this really cool disability justice project in New York called I Wanna Be With You Everywhere, that’s been doing things since 2019. Art in America listed it as one of 20 most significant disability events in America in the last 40 years, or something! They're working on some crip-led spaces of study in the near future.

And Local Organising is ongoing too. The next ones are a secret Halloween party at NUMbrella Lane drop-in, a community hub in Glasgow for sex workers run by National Ugly Mugs—a national charity led by people with lived experience of sex work and allies.

We’re planning a supportive Spa type day requested by a women’s group we work with in the migrant process, as a way they want to help deal with the ongoing pain from past trauma, dislocation of migration, and trying to survive in poverty on an insanely low income.

Also upcoming is a weekend long workshop focused around class and how that plays out in and affects anti-capitalist movements. Next year we will begin with two workshops focused around psycho-emotional health, which will explore radical approaches to health and collective care in the context of movement for liberation and social justice, in a collaboration with the SAU.

The next Episode, funding permitting, will be in November 2026.