Bedri Baykam, Vous Etez Bien Chez Madame Claude, 2025. Mixed media on canvas, 168x239x5,5 cm

Bedri Baykam, Vous Etez Bien Chez Madame Claude, 2025. Mixed media on canvas, 168x239x5,5 cm Bedri Baykam is one of Turkey’s most influential contemporary artists—known not only for his expressive, layered paintings but also for his decades-long engagement with art history, politics, and philosophy. A self-described provocateur, he has spent his career revisiting and reworking the Western canon, not to emulate it but to challenge its authority and reposition its meanings through a critical, often confrontational lens.

Among the many figures he has returned to over the years, none has occupied him quite like Picasso. Baykam's fascination with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon has threaded through his practice since the 1980s, resurfacing in different forms and conceptual frames. His recent Paris exhibition at his representing gallery, Galerie S/Beaubourg, brings this long-running engagement into sharp focus, not merely by reinterpreting the painting, but by dissecting its cultural weight and the mythology of its maker.

Picasso himself enters the picture—alongside Baykam—as a subject of mutual gaze, collapsing historical distance in a swirl of fractured perspectives. In this interview, Baykam speaks about his evolving relationship with Demoiselles, the philosophical grou1111rnd of his practice, and why returning to a single painting across decades can be a radical act of both critique and homage.

Jelena Martinović: Your engagement with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon spans decades. What brought you back to this work now, and how has your relationship with it evolved over time?

Bedri Baykam: Actually, one can never truly predict what triggers inspiration in an artist’s mind—sometimes it comes suddenly and inexplicably. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon first appeared in my life when I was only 12 years old, during an intense school assignment I prepared. That iconic image has occupied a part of my mind ever since.

When I moved to California to study art 45 years ago, I was a young artist going through his struggling years, and from the very beginning, I felt a deep connection to Picasso. I had a close friend back then, a young photographer named Ron Stewart, who shared my fascination with the Spanish master. We would spend hours discussing Picasso and exchanging glances to each other’s sketches.

In 1981, I painted what I consider my first major work: The Prostitute's Room. It was an unusual and powerful fusion of Cubism and Expressionism. The painting portrayed one of Picasso's women—reimagined as a prostitute—removing her underwear. There were broken mirrors on one side and a human silhouette, so that viewers would see themselves entering the room, as if becoming part of the scene. That work marked the beginning of a personal and lasting relationship with Les Demoiselles, one that kept evolving conceptually and emotionally over the years.

Women remained a source of inspiration for both Picasso and myself throughout our lives. So it's only natural that the seed planted in me at the age of 12 took root and began to bloom—first with that 1981 painting, and later in many other forms. Over time, it grew into a constant presence within me, as if implanted permanently.

But don't get me wrong—those who know my work understand that I'm a very versatile artist. I've created deeply political exhibitions, thoroughly grounded in historical research. I’ve produced large-scale Livart installations that immerse the viewer and engage all five senses. These were like some sort of what I would call "small Disneyland of art." I’ve also developed extensive lenticular series, which exist as a unique visual world of their own. For anybody who hasn’t seen them, lenticulars, can carry some 15 to 25 layers of depth and they look like magical dreams! They are unique looking pieces that don't look like any other type of art work; So it's not that I've ever been fixated on Les Demoiselles d'Avignon—even during periods when I wasn’t directly working with it, the essence of that painting continued to live inside me.

JM: In this exhibition, you're not simply reinterpreting Picasso—you’re dissecting, reframing, and at times directly confronting him. What possibilities does this critical dialogue open up for you?

BB: To be honest, for many years I've been dissecting Picasso's life—almost as if I were entering his mind. I've tried to understand what led him to certain decisions, how he related to his various long-term lovers and to women in general. This exploration sometimes allows me to place myself in his shoes and try to grasp what drove him.

For example, I can understand his relentless passion and determination to succeed. I can sense how profoundly he was affected by the suicide of his best friend Carles Casagemas in 1901. I imagine how deeply he felt not only loss, but perhaps a sense of having been abandoned or let down. Similarly, I can empathize with the frustration he might have experienced in 1905, when the Fauves—Matisse, Vlaminck, Van Dongen, Derain—took the spotlight at the Grand Palais with their wild, vibrant colors. Critics, including Louis Vauxcelles, dubbed them "Les Fauves" (the wild beasts). I don't think Picasso was jealous, but I believe he must have envied their sudden notoriety, even if it was a succès de scandale. He realized he had to regroup and prepare his next move.

That's when he traveled with his girlfriend Fernande to the small mountain town of Gósol in the Spanish Pyrenees. Over the course of some 80 days, he created hundreds of sketches—many of which included a medical student and a sailor in total in Gosol and Paris. As we know, these two male figures were later removed from the final composition of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

During this period, he was also looking closely at works by Derain, Gauguin, Cézanne, and Ingres’s The Turkish Bath. His mind was a melting pot of visual references—Orientalist themes, harem scenes from old Istanbul, and echoes of Western masters. In Gósol, he created preliminary paintings that began to bring these fragmented ideas together.

Fernande, along with the 90-year-old innkeeper they befriended, provided a sense of safety and grounding in this otherwise unfamiliar place. That sense of comfort allowed him to fully immerse himself in what was a risky visual and conceptual leap—a radically new direction for modern art.

After returning to Paris, he was finally ready to execute what would become Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. And here, I'd like to add something that I feel qualified to say—based on my extensive research into Picasso's psychology and artistic process. In the early 1900s, Picasso had been living in Paris with his friend Casagemas and three French women: Odette, Antoinette, and Germaine. Casagemas was in love with Germaine but he could not tie the knot. In 1901, while Picasso was away, Casagemas unsuccessfully attempted to kill Germaine and then committed suicide. Picasso was devastated and deeply shaken.

Years later, while working on Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, I believe the memory of Casagemas's death remained imprinted on Picasso's heart—and in the painting. One of my own works in this series addresses this very element, as I feel it is an essential, often overlooked emotional layer in the story of this masterpiece. By the way, many people think the name of the painting comes from some young ladies Picasso had befriended in the city of Avignon in France. But in fact the issue was that on top of his girlfriends, he kept going to a bordello in “Calle Avinyo”, the name o0f the street. The name of the work comes from there. The first name was "The Philosophical Bordello," given by his group of writer friends, Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire, Andre Salmon, and maybe also his artist friend Andre Derain.

JM: These works invite a play of gazes—Picasso looking at you, the women gazing out, you looking back at him. How do you see this multiplicity of perspectives shaping how viewers encounter these works?

BB: Yes, it really feels like a continuous ping-pong game. I look at Picasso, I sense him looking at me. The women in his paintings—and the women in mine—seem to return our gaze. And then I look back at him again, often wondering how he would respond to this or that work of mine. There's a multilayered loop of glances and interpretations at play.

This was also insightfully observed by the renowned Turkish art critic Hasan Bülent Kahraman. For example, one of my early works—a photographic collage from the very first Istanbul Biennial in 1987—keeps resurfacing in my mind when I work on these themes, I Wish I had a Harem. In that piece, I appear wearing a Groucho Marx style hat, sitting among the Demoiselles women. It's as if I've replaced the absent figures—the medical student or the sailor originally sketched but ultimately removed from Picasso's final composition.

This year, I even reconstructed the composition in a new way: This time, instead of me, it's Picasso who is surrounded by his own personal "harem"—his wives, lovers, and muses. Of course, I can't help but imagine how much I would've loved for him to see this piece and tell me what he thinks! About those two compositions, I have another work talking about "the duel of the Harems."

Personally, I feel Picasso was most at ease—especially in the early stages of the relationships—with Fernande, Marie-Thérèse, Françoise Gilot, and Dora Maar. I had the chance to meet Françoise Gilot in New York in 1984, at the home of a Polish art dealer.

There is a persistent erotic tension—sometimes hidden, sometimes overt—in the atmosphere of his work. Picasso's libido often served as both ignition and fuel for his creativity. I sense that he needed to desire a new woman in order to spark a new artistic phase, almost in an orgasmic, primal way. In his art, women were simultaneously gasoline and battery—both the energy and the charge. And I am among the few who perhaps understand this duality most intimately.

JM: Elements of Turkish visual culture—from shamanic echoes to Siyah Kalem—surface subtly throughout the show. How do these cultural undercurrents inform your rereading of a Western modernist icon?

BB: Let me begin by saying: for this series I've immersed myself in—especially this year—nothing is finished. You know when you're playing roulette in a casino, and the croupier calls out, "Les jeux sont faits, rien ne va plus"—the bets are placed, no more changes allowed? Well, I'm nowhere near that moment. I feel new seeds are being planted every day and new ideas pop up all the time!

I believe there will be more works to come—especially ones where photography blends more intimately with painting. Let’s not forget that I’m a connoisseur in all the flirts between photography and painting. I also still have more abstract feelings about what’s yet to come.

Now, if we zoom out and think about the centuries-long dialogue between artists across time, we enter into a dance with the very concept of "time"—sometimes denying it, sometimes fighting it, and often surrendering to it. Think of Picasso's relationship with Velázquez or Manet. Similarly, I engage with Picasso, just as many other contemporary artists around the world do in their own ways.

In one of my new pieces, for instance, I fuse elements from Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, African masks, and the demons of Siyah Kalem—Muhammad of the Black Pen. I called these "Liaisons Dangereuses," which means dangerous relations… I truly believe that if Picasso had known the work of Siyah Kalem, he would have loved it—just as he was fascinated by African and Iberian sculpture. He didn't have access to that connection, so in a way, I'm making it on his behalf.

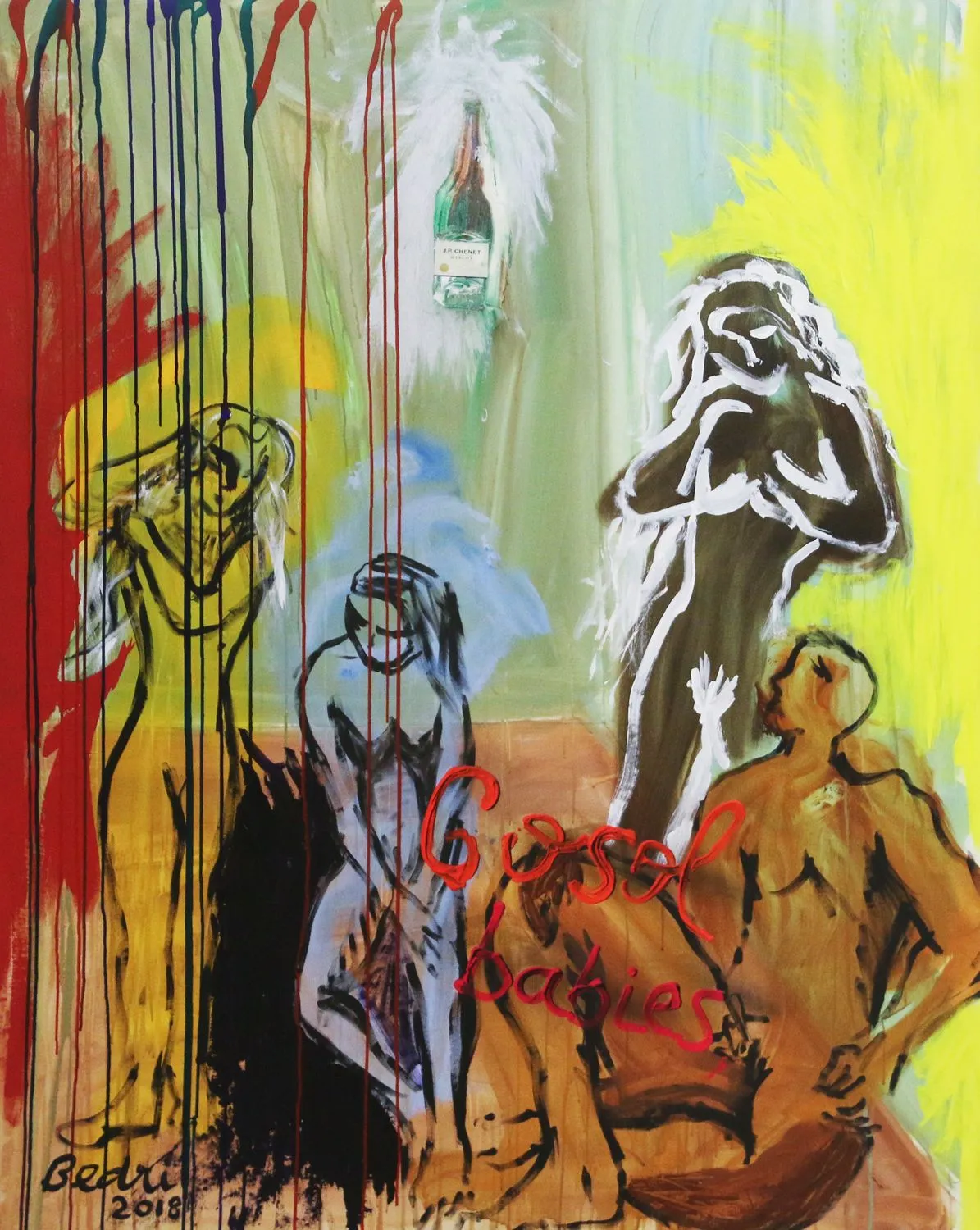

I also made two leaps forward, making works around Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, once through a Turkish Bordello in Istanbul called "Varol" and also another world famous classy French Bordello "Madame Claude" about which I made three works. Both of these "institutions" are from the 60’s and 70’s…

And still, I'm far from being done. It's almost tragic that after all the intellectual and emotional effort we invest in our artistic journeys—through historical research, conceptual exploration, and creative labor—we often have to leave this world with many things unfinished. But that's the nature of art: it is transtemporal, transcultural, and profoundly human. The more universal your gaze becomes, the richer and more fertile your field of creation.

JM: You've spent your career challenging dominant Western art narratives—from confronting Orientalist tropes to questioning who defines modernism. In revisiting Les Demoiselles, how does this exhibition continue that resistance? And what, if anything, has shifted in the global art landscape since you first took on these themes in the ’80s?

BB: It's hard to believe that it's been 41 years since I distributed my manifesto at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1984, and 36 years since the one that caused a stir at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Looking back, I'm grateful that time has proven me right—many prominent critics, including Peter Selz, Edward Lucie-Smith, Harry Bellet, and other Berliners, eventually revised their discourse following years of my persistent rhetoric.

In 1987, during the 1st Istanbul Biennial, I presented a 10-meter-long installation titled Ingres, Gérôme—This Is My Bath. It's now part of the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art and remains on view. The work confronted two iconic Orientalist painters who famously used Eastern subjects like the harem and Turkish bath. I’ve always maintained that anyone is free to engage with such themes—these are, after all, universal human subjects. But what's unacceptable is the hypocrisy: when we, as Eastern artists, return to these same subjects from within our own cultural heritage, we are accused of mimicking their style—as if these themes belonged to the West just because they painted them first.

This double standard is persistent. In my book Monkeys' Right to Paint, there's a spread—page 122—123, where I place three visuals side by side: one by an ancient Zaire artist, another by Paul Klee, and a third by A.R. Penck. I could've easily added a fourth work by Keith Haring. Here’s the point: if I had painted in that same style, critics would have said, "Oh, Baykam is imitating Penck or Haring." No one would say, "This Turkish artist is drawing from African visual heritage." Why? Because in the eyes of the global art establishment, once a Western artist adopts a visual element from another culture, the copyright somehow passes on to them. This attitude has repeated itself in the cases of Giacometti, Brancusi, Henry Moore, Max Ernst, Motherwell, and many others.

Yes, the art world appears to have changed over the past four decades—but much of it is only surface-level. If you study auction results, major retrospectives, institutional exhibitions, and museum hangings, you’ll notice that around 80% still revolve around the same canonized Western artists. Western museums are rarely willing to give serious attention or retrospectives to a Turkish, Colombian, or Thai artist unless it's part of a temporary “multicultural” gesture. Often, it’s less about genuine curiosity and more about appearing inclusive.

This is the makeup of the system, and it's barely changed. Don't forget, my fight against the Western art world's hegemony started almost a decade before "multiculturalism" became fashionable in the 1990s. I was simply "too early." Les Demoiselles Revisited continues that same resistance. Once again, I am asserting that time, modernity, and cultural heritage are not the sole property of the Western world. They belong to all of us, the citizens and artists of the world…

Let me put it another way: for decades, the West has acted as if it holds exclusive rights to serious subjects—like cancer, COVID, or AIDS research—while telling us, "If you know of any local herbs that cure snake bites, feel free to share." Even then, you know they'll later take that copyright also and claim it as their own discovery. That mindset persists across all fields, including art.

This exhibition also features my Art History Map—a conceptual work that offers a more universal perspective on art history. It includes all major Western names but refuses to omit the rest of the world, unlike traditional Western-dominated timelines. Many visitors have been drawn to the map's sweeping and inclusive vision. It challenges the oversimplified, auction-price-certified narratives that dominate most museum programming, where each decade is presented as the triumph of a narrow Western elite.

In short, there's still no true "Olympics of the arts." It's like staging a global race, but only allowing Western runners to wear proper shoes, have water, and rest, while everyone else is forced to compete with a bowling ball chained to their leg and no nourishment for 48 hours! Yet the Western establishment still insists this is a fair game.

How can we talk about fairness when so many artists around the world can’t even obtain visas to travel to the centers of the global art world? Just recently in Turkey, two young sopranos who had qualified for the semifinals the prestigious Tullio Serafin İnternational Opera competition in Italy; they were denied visas by the Italian Consulate in Istanbul. They couldn't compete. They lost their opportunity. And of course, Italy doesn't care, the world doesn't even know!

All of this—these decades of asymmetry and struggle—is part of why I launched World Art Day in 2011. During my presidency of the International Association of Art (IAA), I succeeded in having UNESCO officially recognize April 15—the birthday of Leonardo da Vinci—as World Art Day in 2019. And just as we envisioned, no permission is needed from anyone to celebrate it. People around the globe—artists in Pakistan, Sweden, Mexico, Korea, Türkiye, and beyond—honor the day through exhibitions, performances, speeches, or simply sharing online. The logo we created in 2012 is free to use. On that day, everybody feels equal and happy about the arts in general… Unlike the other days.

This is one of the contributions I'm most proud of in my career.

No, I'm not naïve. One of my paintings from 1984 reads: "This will be a very long fight"—we may win in 50 or even 100 years. But that fight is still worth it. And I'm still here, continuing it.