Whole Cloth installation view, Claire Oliver Gallery, 2024

Whole Cloth installation view, Claire Oliver Gallery, 2024 In recent years, textile arts have been experiencing a renaissance, especially regarding increased presence in major shows and institutions. Recent high-profile examples include the 60th Venice Biennale, where fiber art was among the dominant mediums, and the Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction exhibition, currently touring the US and Canada. However, for artists who have dedicated their lives to this medium, such as American artist, writer, and curator Carolyn Mazloomi, textile arts have always been central to their personal and artistic pursuits.

Growing up in the South during the Jim Crow era, Carolyn Mazloomi experienced racism, and as she recounts, not one member of her family was spared from this malice. Witnessing the injustices and violence Black people endured in the US left a deep wound, and she later discovered quiltmaking as a powerful tool for addressing these issues.

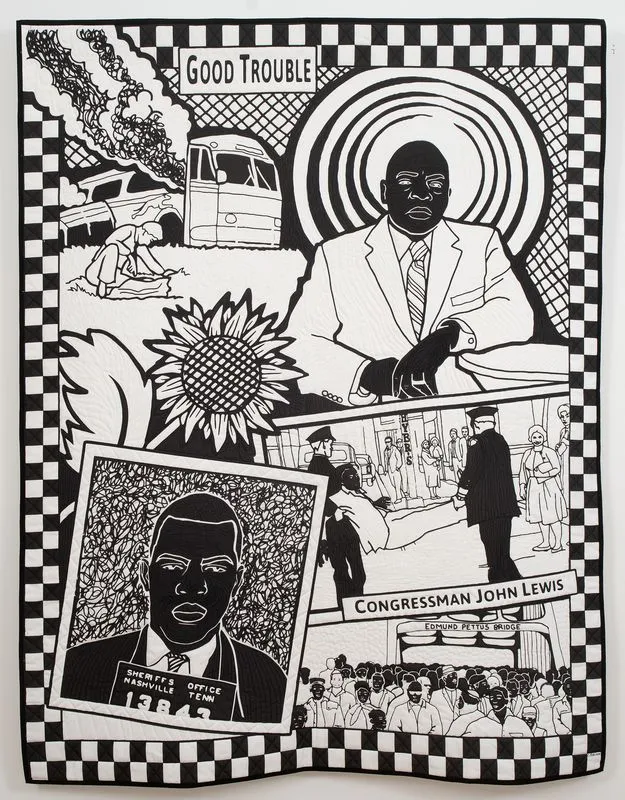

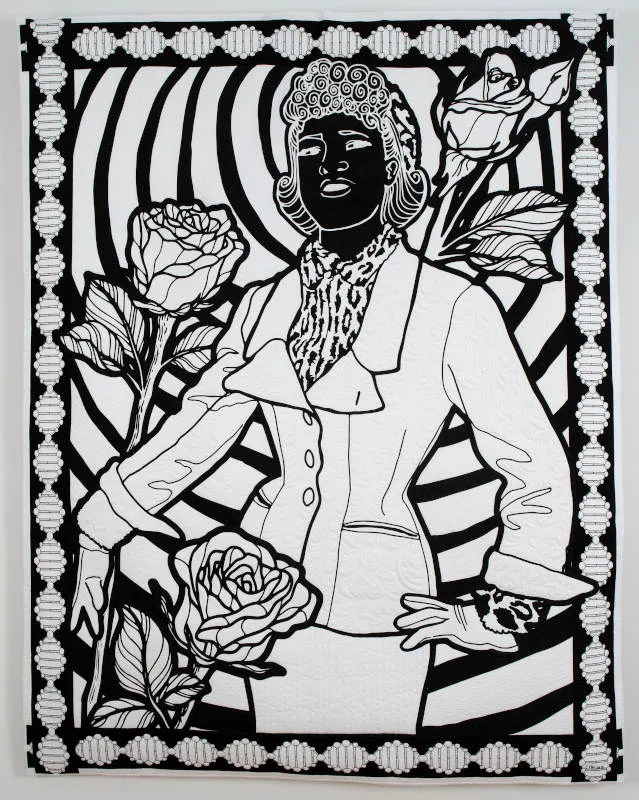

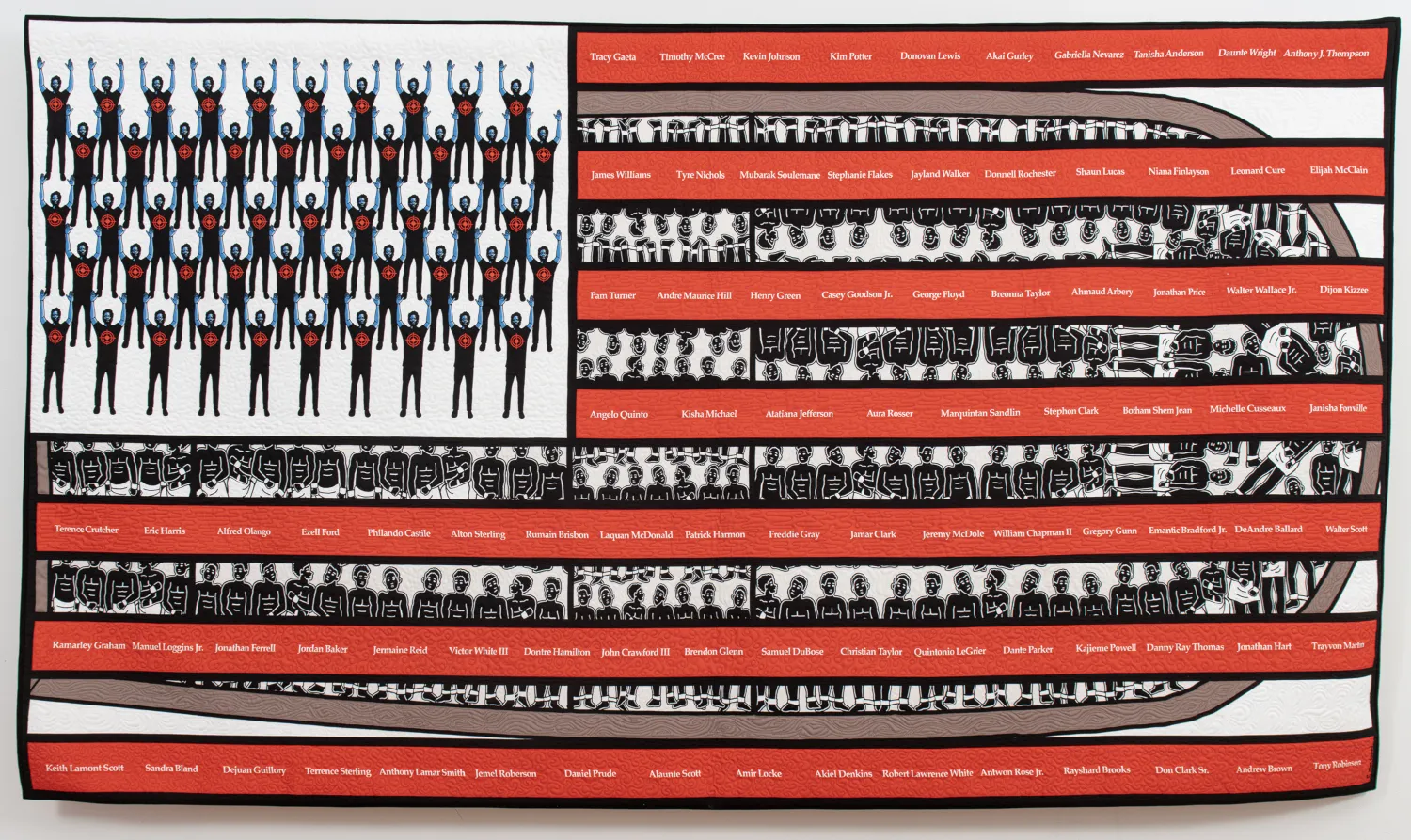

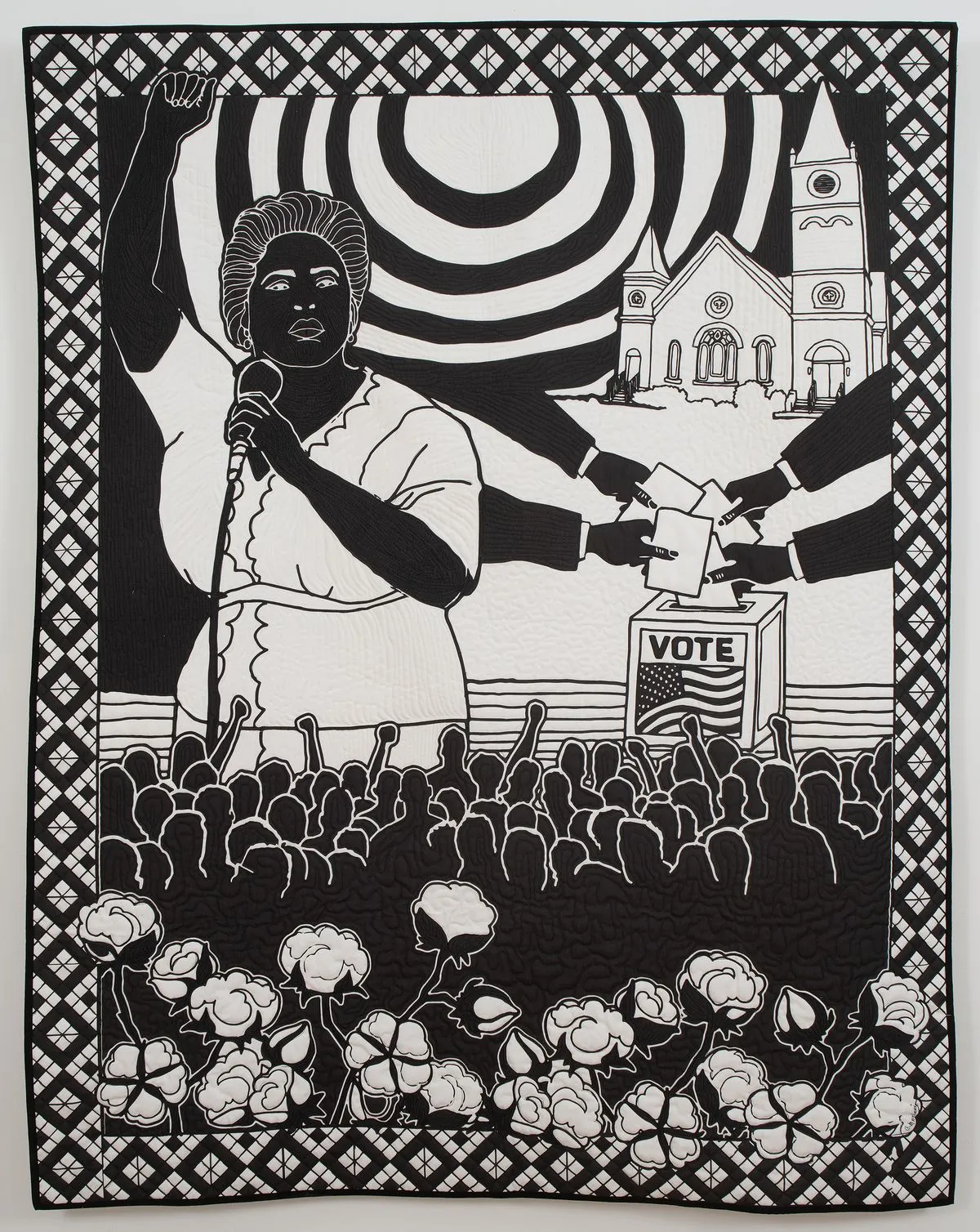

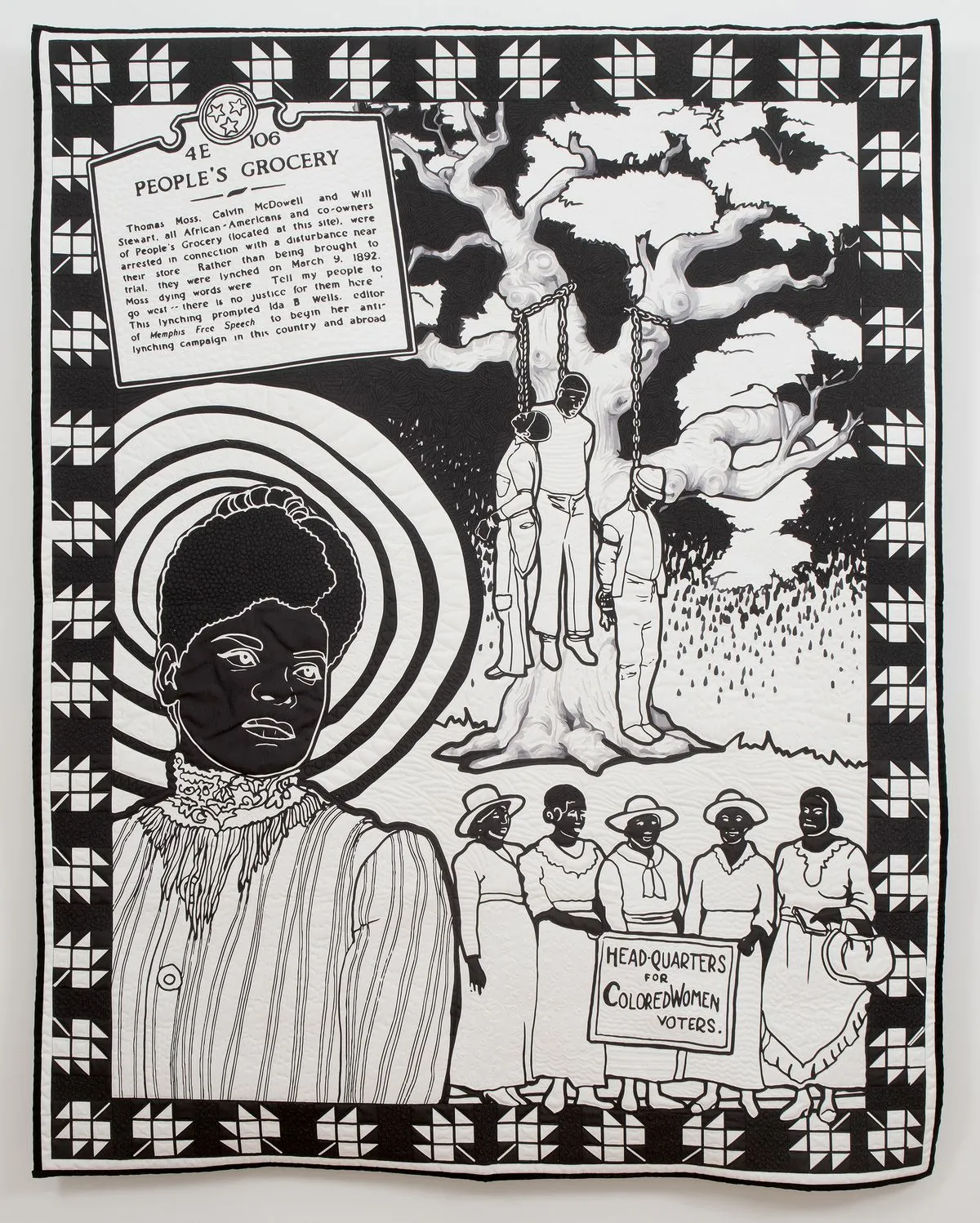

The exhibition Whole Cloth: Narratives in Black and White at Claire Oliver Gallery centers on Black civil rights activists, but Mazloomi’s work is also deeply connected to the broader history of her people, which is still not known well. This unknowing, she explains, leads directly to misunderstandings, rejection, and mistrust that color relationships between black and white communities in the country. Art can deal with the tough stuff that nobody wants to hear, she asserts, and this is indeed true, considering the topics and political stances artists highlighted in recent years. However, Mazloomi's quilts are not just reflections on the state of affairs; they are also a call to action, as the artist seeks to inspire profound personal reflection in each viewer.

By pointing to both the positives and the negatives, Mazloomi aims to show that, in the end, it all depends on us, and our attitudes that need to be altered. Her black and white quilts, reminiscent of old photographs, newspaper articles, and activist prints, engage, both narratively and affectively, in this work. With African American history being increasingly erased from school curricula throughout the US, she sees art as the last bastion for preserving neglected and erased histories and for educating others about this often-overlooked past. Attitudes can change through knowledge and understanding, and her art assists in this endeavour.

Tireless and tenacious, Mazloomi is also known for her curatorial and written work, which give her a multifaceted perspective on art and history. She is also a recipient of numerous national awards for her art and has been inducted into the Quilters Hall of Fame Museum. In 1981 she founded the African American Quilt Guild of Los Angeles and a few years later the Women of Color Quilters Network (WCQN).

Currently celebrating her first solo gallery show, Mazloomi took time to converse with us about her artistic journey, her passion for quiltmaking, and the political and activist aspects of her art, which is finally receiving its due recognition. She guideed us through her practice, her dedication to Black history, and the goals she has set for her art that her current show continues to build toward.

Biljana Puric: Could you share how your artistic journey began and what inspired you to focus on quiltmaking as a primary mode of storytelling?

Carolyn Mazloomi: I started making quilts over forty years ago; I like the medium because I love the tactile nature of the fabric. I also like quilts because they are easy to store and ship if you're doing an exhibit.

BP: How have your family relationships and upbringing in the Jim Crow South shaped your practice, particularly your focus on quiltmaking? In what ways do these personal experiences and cultural ties influence the narratives you choose to depict?

CM: I am an elderly African American woman who is a wife, mother, and grandmother, born and raised in the Jim Crow segregated South. This fact of my life never leaves my psyche, and it influences just about everything I do. I remember the pain and horror of that time in my life. Every member of my family and close friends suffered from some form of discrimination or racism during this period.

I remember the courage and bravery of the Civil Rights workers who marched on behalf of African Americans who sought justice, equality, the freedom to vote, attend decent schools, and live wherever they wanted. These brave people put their lives on the line. Not knowing if they would make it back to their loved ones while out marching for civil rights and social justice and trying to register people to vote. I want to celebrate their lives and tell the stories of their brave deeds. I don't pick one over the other when I tell the stories in quilts. Each of them deserves a seat at the table, and I will continue to celebrate them in my work for the rest of my life. They deserve that. I am because of them. I cannot do enough to honor them.

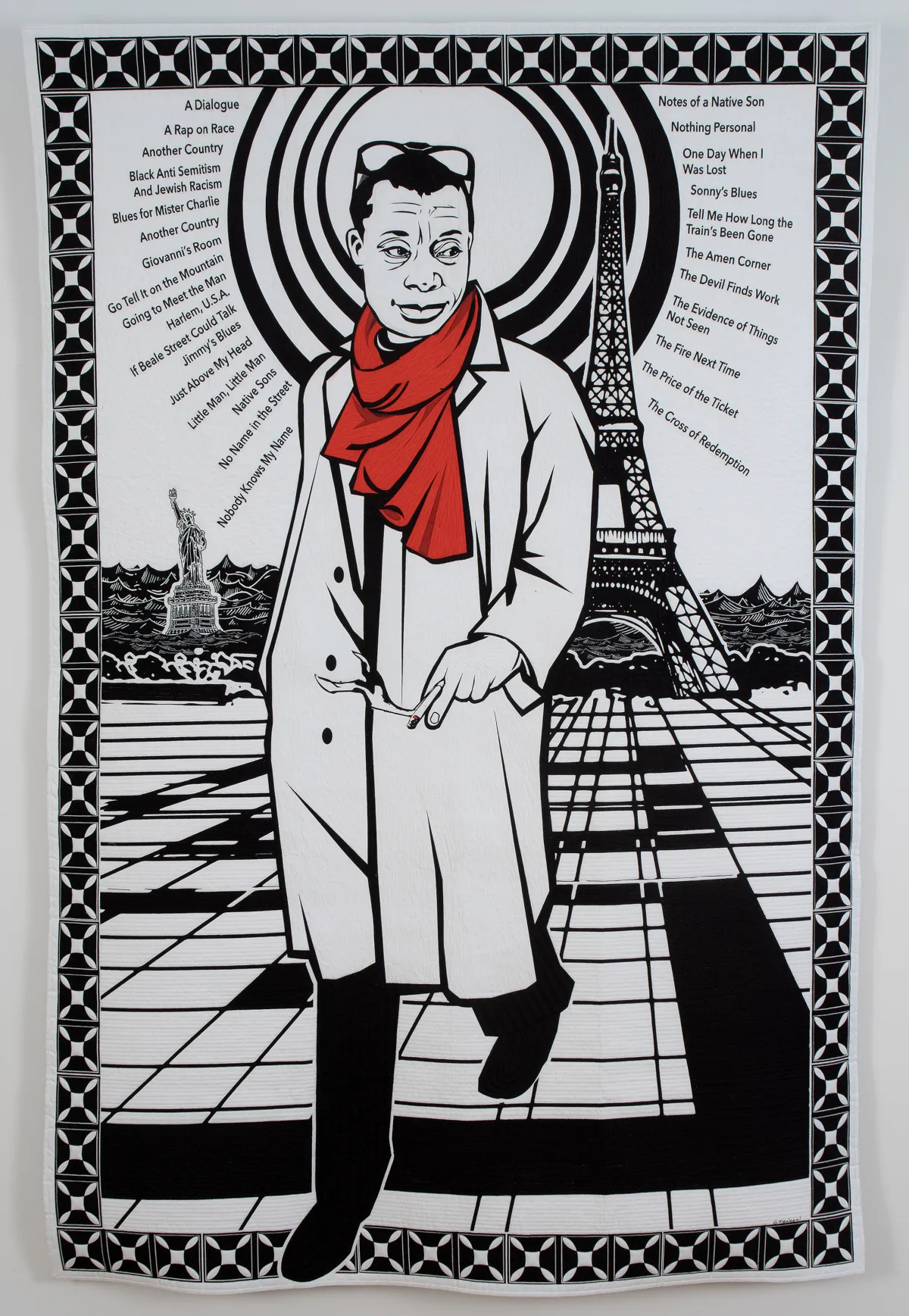

BP: Color plays a significant role in your work, especially the use of black and white with occasional red accents, which evoke newspaper photographs and politically charged visuals. How do these color choices reflect the themes in your work, and what emotions or ideas do you hope to evoke through this palette?

CM: Creating artwork in only black and white emphasizes contrasts, shapes, and textures without the distraction of color. It allows the viewer to focus on composition and form, which often evokes strong emotions and messages. Additionally, black and white can evoke a sense of timelessness and nostalgia, making the artwork feel more universal and relatable.

This work can also challenge the viewer to engage with the piece on a deeper level, interpreting it through light and shadow rather than color. There's nothing to get between the message I want to convey to the viewer. The starkness of black and white is simple. My black and white works also symbolize racism in the country—one of the biggest problems in this country. There is much drama surrounding the relationship between white and black people in America.

BP: Your quilts blend figural imagery with geometric patterns and recurring circular motifs, which resonate with quilting traditions. How do you see your work as both a continuation and evolution of these traditions? What significance do the geometric elements hold in your storytelling?

CM: The circles in my quilts represent the interconnectedness of all things and unity. The borders of my quilts usually have some type of patchwork design. It is my way of paying homage to quilters that came before me.

The continuation and evolution of quiltmaking are centered around techniques and skills, cultural heritage, and evolution. Many traditional quilting techniques, such as piecing, appliqué, and hand-stitching, are still practiced today, preserving the craftsmanship and artistry of earlier generations. In fact, I consider these skills the foundation of all quiltmaking.

Cultural heritage is important to quiltmaking. Quilts often reflect cultural narratives, community stories, personal histories, and the passing down of traditions and values through the use of fabric. Quilts are constantly evolving. Today's quilters use modern designs, which frequently incorporate innovative patterns, bold colors, and abstract designs, moving away from traditional motifs.

The "art quilt" and the "modern quilt" are popular movements in quilt communities around the world. The materials from which quilts are made are changing every day. The use of new fabrics, including synthetic and repurposed materials, expands the possibilities for texture and durability, allowing for greater creativity. Quilters use a variety of materials that are not fiber, such as wood, plastic, paper, feathers, etc.

Advances in technology, such as computerized sewing machines, innovative tools, and digital fabric printing, enable quilters to explore new techniques and achieve previously unattainable precision. Contemporary quiltmakers often address modern social issues, using quilts as a medium for activism and personal expression, thereby shifting the narrative and purpose of quilting.

Quilting today honors its roots while embracing change, making it a dynamic art form that reflects both the traditional and innovative. The art form is continually evolving.

BP: Your quilts often depict historical events and figures that have shaped the Black American experience, with an emphasis on both commemorating and preserving knowledge threatened by conservative political forces. How do you envision the role of art in challenging historical erasure and educating the public?

CM: Quiltmaking amplifies marginalized voices of people who, at one time, during slavery, were not allowed to read and write. Art was the only voice they had. Narrative quilts highlighted stories and experiences of their communities that are often overlooked or misrepresented in mainstream narratives. This representation fosters a deeper understanding of the diverse histories of America.

Art creates dialogue by bringing attention to underrepresented histories. It encourages conversations about societal issues and injustices, prompting viewers to reflect on their own perspectives. Art can deal with the tough stuff nobody wants to hear.

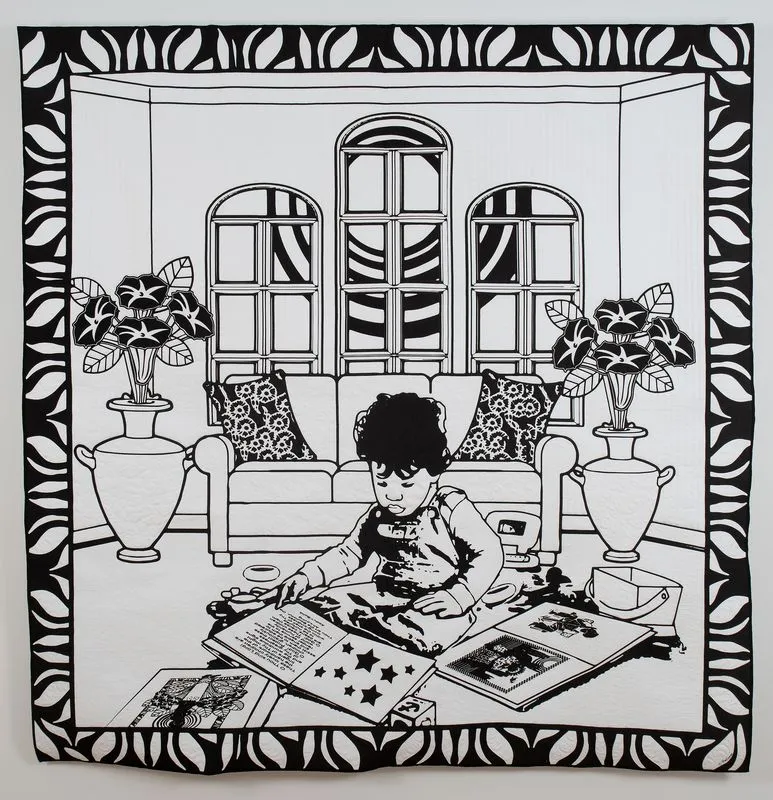

I am a storyteller. My quilts are narratives that tell stories, which can sometimes be very emotional for the viewer. Art has the power to tell stories that resonate on a personal level, making historical events more relatable and engaging. This emotional connection can inspire empathy, a desire to learn more or provoke fear and anger. The latter is not what I would want a viewer to experience, but sometimes does happen.

National statistics show most Americans are not readers. They are mostly visual learners. Seeing art can simplify complex historical narratives, making them more accessible to a broader audience, including those who may struggle with traditional educational formats.

I often critique dominant historical narratives, using the work to question established truths and provoke thought about whose stories are being told and why. Using quilts, I can prompt viewers to reflect on the implications of historical events and contemporary issues, encouraging a more nuanced understanding of the past. This is especially important at this time in our country's history. Over thirty states have implemented laws prohibiting the teaching of African American history. Making narrative quilts, which have been added to museum collections, is a way to show this history. Artworks document and preserve histories that might otherwise be forgotten, ensuring that future generations can learn from them.

My quilt art not only challenges historical erasure but also serves as a powerful tool for education, encouraging critical thinking, emotional engagement, and a deeper connection to our shared histories.

BP: You emphasize the qualities of quiltmaking—comfort, intimacy, care, and nurture. How do these inherent qualities of the medium interact with the political messages in your work? How do they serve to enhance the stories you tell.

CM: Narrative quilts are an easy and familiar way to tell difficult stories. The tactile nature of quilts, with their fabric and stitching, evokes a sense of warmth and comfort, contrasting with often difficult themes my quilts address—themes such as racism, social justice, and historical trauma.

Quilting as a traditional craft carries cultural significance, particularly within African American communities. It is a historical art form which has been studied by many scholars. My use of quilting connects political messages to a lineage of women's labor and artistry, emphasizing the importance of heritage and collective memory.

The visual language of my quilts symbolizes resilience, community, and hope while also critiquing systemic injustices. Many quilts tell stories, using imagery that reflects historical events and personal experiences. By incorporating historical references and my personal experiences into my quilts, I address the erasure of African American narratives. The work serves as a counter-narrative, reclaiming space in the art world for these important stories.

I consider myself an activist. Quilting becomes a form of activism that seeks to provoke thought and inspire action. The quilt becomes a platform for dialogue about race, identity, and social change.

Quilts are a long-lasting art form offering timelessness and permanence. They are often seen as heirlooms, linking generations.

The qualities of quilts—such as their tactile nature, cultural significance, and storytelling potential—interact powerfully with my political messages, creating a multifaceted dialogue that engages viewers on emotional, intellectual, and social levels.

BP: Your creative process begins with sketchbooks and diaries before translating to textile art. Could you take us through your process from the initial concept to the finished quilt? How do you balance intuition with technique?

CM: It is very important for me to draw my work on paper. I do the same in writing. I've written fifteen books, and all of them were handwritten first. I love using a lead pencil and the act of drawing is relaxing for me. Drawing is a time for reflection and makes it easy to explore ideas and feelings. I feel a sense of grounding when I draw with a pencil. I choose a drawing from one of my sketchbooks, digitize it, and make it the finished size I want to see. Then, I send the digital image to a textile printer and have it printed on cotton fabric. When the fabric is returned, it is sandwiched with cotton batting and a cotton fabric backing and quilted. The act of quilting the stitching onto the work is physically demanding and time-consuming. I have people who help me do the actual quilting.

BP: In addition to your artistic practice, you're an author and curator. How do these roles influence your approach to art? Have there been any recent curatorial projects or exhibitions that have particularly impacted your own work?

CM: As a writer, I focus on narrative development that can contextualize artworks. This enhances my ability to articulate the themes and concepts of my quilts, helping to create a richer understanding for the audience.

Writing allows me to explore history and shape how I interpret artworks in exhibitions and discuss the works included.

My background in writing encourages me to delve into the historical and cultural contexts of artworks. This informs my curatorial choices, ensuring that exhibitions are not only visually engaging but also intellectually grounded. The goal is to have powerful works that draw on emotion and can draw connections between individual pieces and larger societal themes, making art relevant to current conversations about identity, politics, and culture.

Writing fosters critical thinking skills, allowing me to analyze artworks more deeply. This analytical approach informs my curatorial decisions, ensuring a thoughtful selection of pieces that engage the audience. I can develop cohesive themes for my quilts using writing to outline concepts that connect various works and provide a narrative thread throughout exhibits such as the one at Claire Oliver Gallery.

Because I'm a writer, I can craft artist statements and exhibition catalogs that effectively communicate my intentions, thereby enhancing the audience's experience and understanding of the work. Writing about art in an accessible way helps bridge the gap between complex concepts and diverse audiences. This is crucial in curatorial practice to ensure that exhibitions resonate with a wide range of viewers.

Being a writer and curator allows me to approach art through a multifaceted lens, blending narrative, analysis, and contextual understanding to create engaging and meaningful experiences for both artists and audiences.

BP: Textile art, and quiltmaking in particular, have gained renewed recognition in recent years, especially with the rise of interest in craft and women's practices. Have you encountered resistance to your medium during your career, and how have institutions responded to your work? How do you see the evolving appreciation for textile art shaping the future of this field?

CM: As a curator, I've encountered resistance by some museums to exhibit quilts because they don't see them as art. For those I've convinced to exhibit, many found their museums had the largest viewer traffic for quilt exhibitions. The public loves quilts, and these museums have returned many times to rent quilt exhibits!

BP: Your quilts depict powerful narratives of bravery, compassion, and resilience. What do you hope viewers take away from engaging with these stories?

CM: When I was a young person growing up in the South, the only history we ever learned about was that of white people. Black history has not been taught in the schools. Most white people know little, if anything at all, about Black history. I firmly believe the perception white folks have of Black people would change if they knew our history. This is why I will continue to make story quilts about Black history. I want people to be educated about the trials, tribulations, hopes, dreams, and accomplishments of my people.