Daniela Ortiz. Courtesy of the artist.

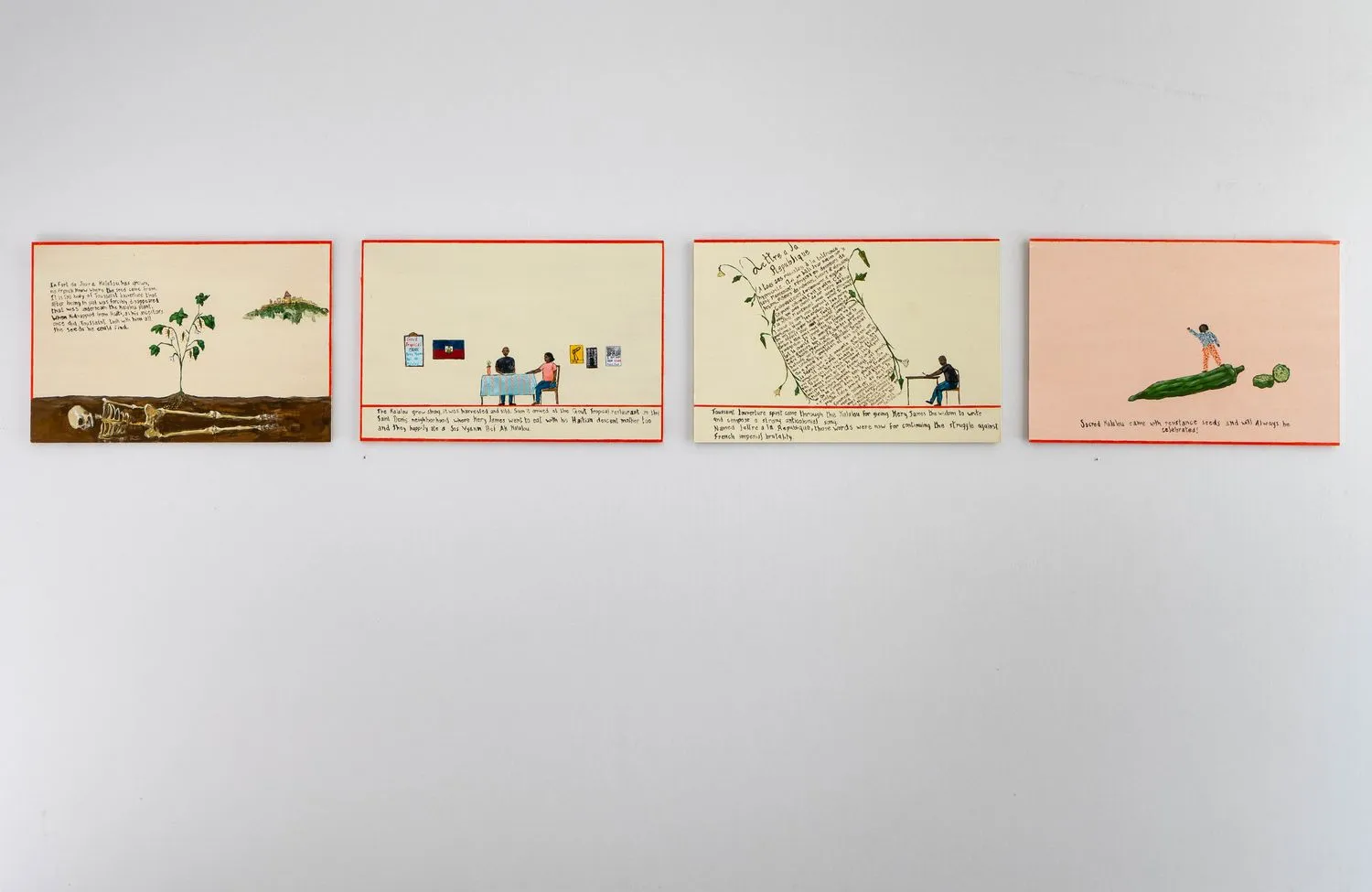

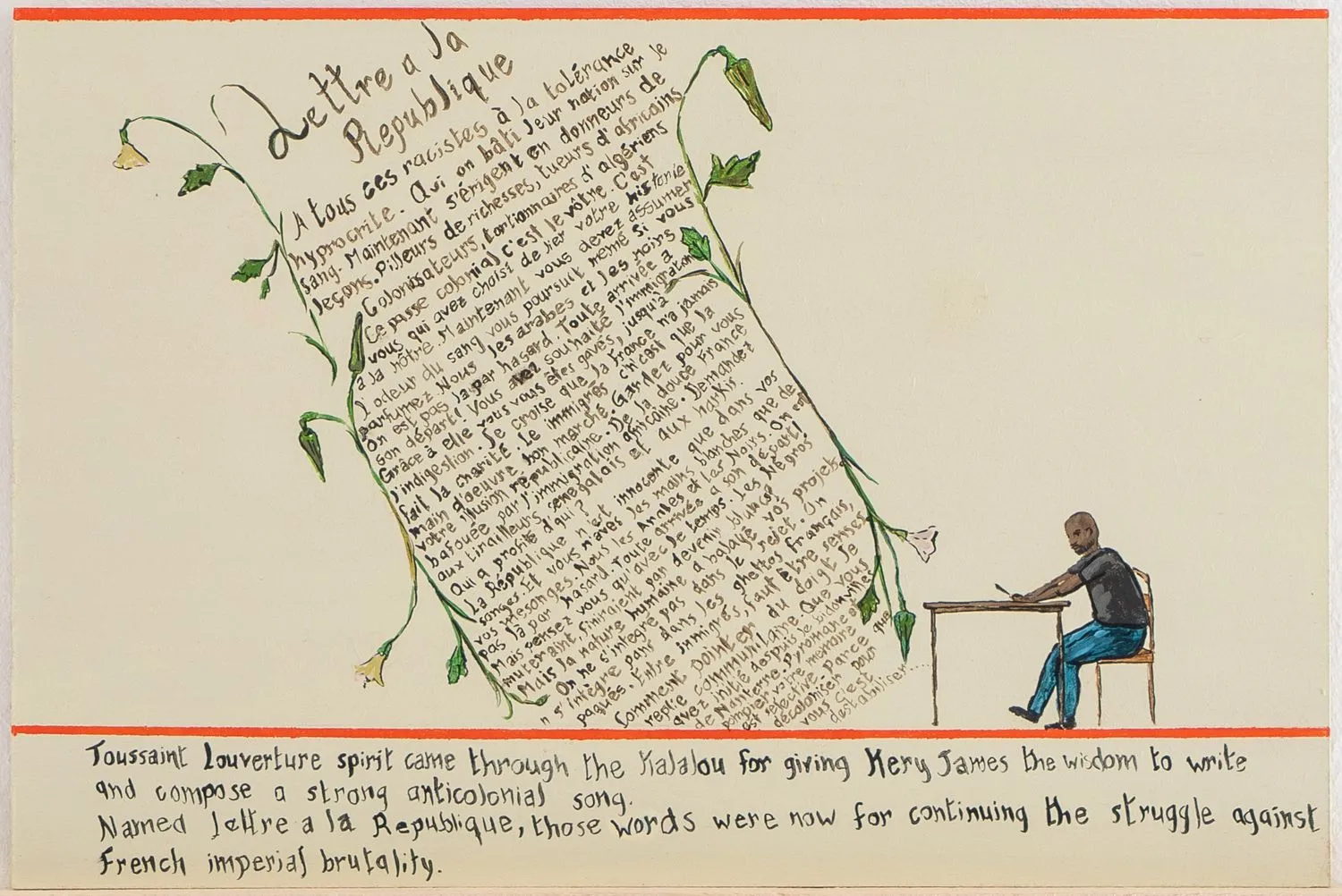

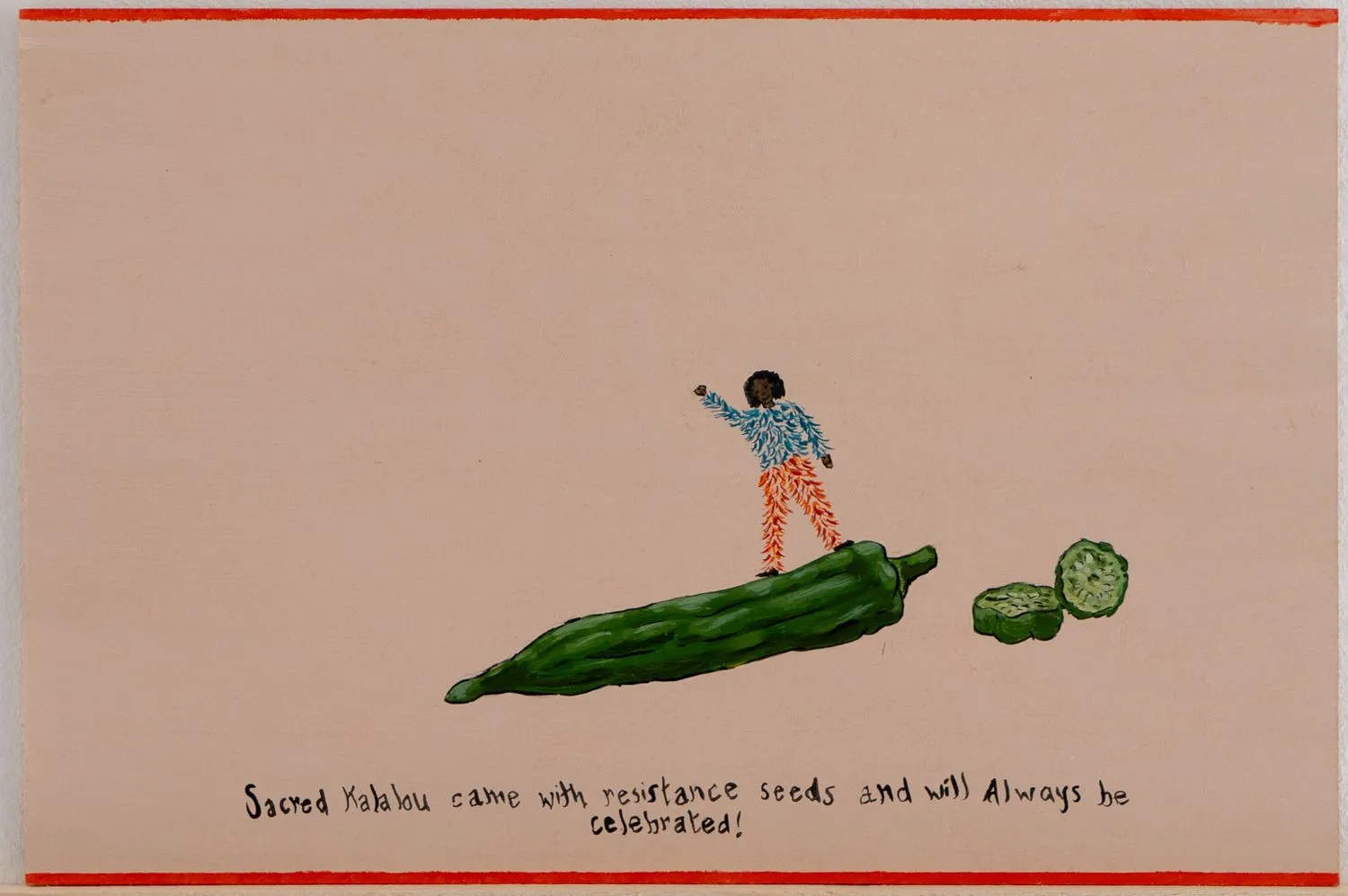

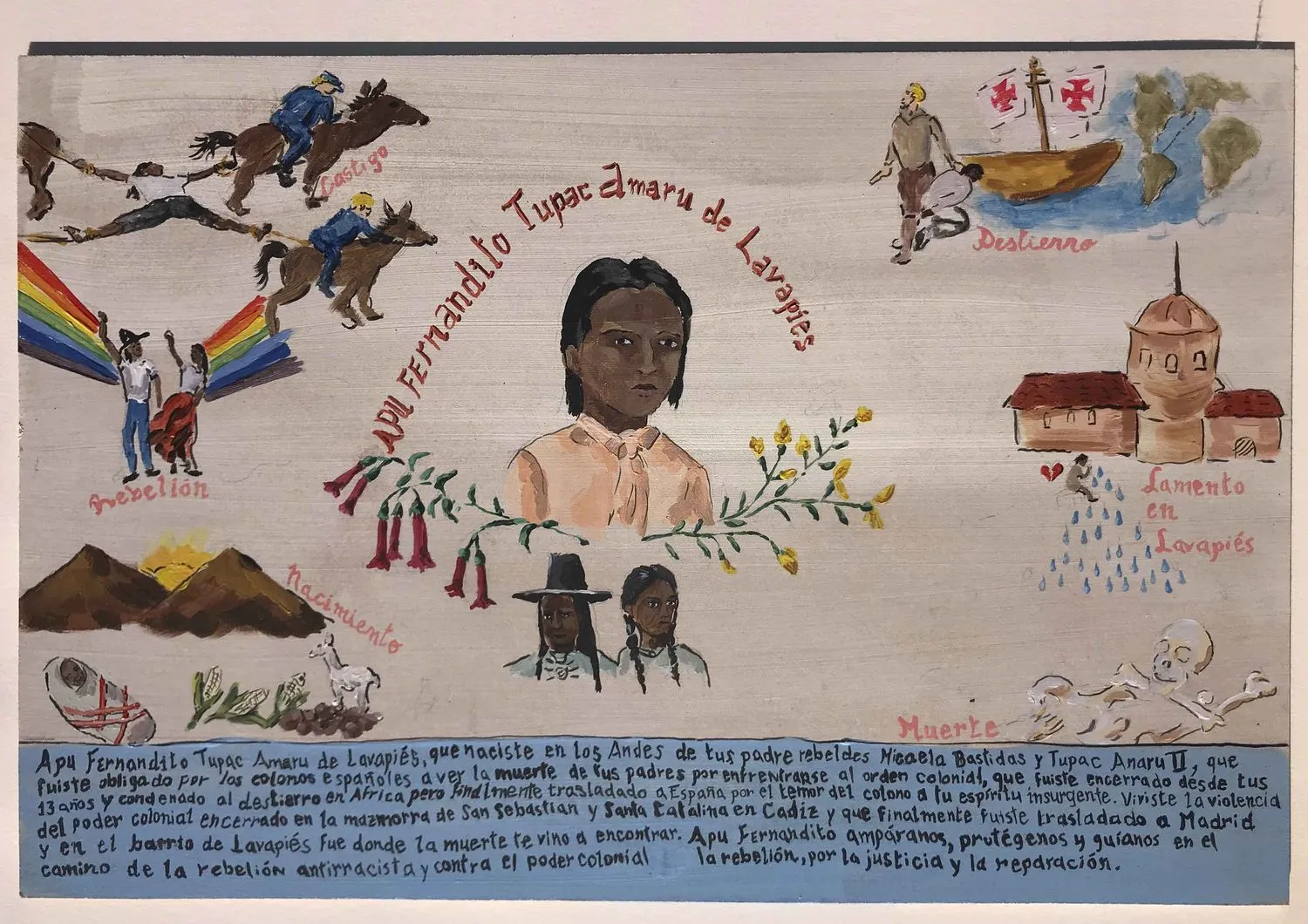

Daniela Ortiz. Courtesy of the artist. Peruvian artist Daniela Ortiz engages with colonial histories, systemic inequalities, and resistance movements through a practice that spans painting, sculpture, video, photography, and performance. Her work critically examines the structures that perpetuate exploitation and exclusion, offering alternative narratives that center justice, equity, and marginalized voices. Ortiz’s practice challenges entrenched power structures while foregrounding the voices and histories of those often excluded from mainstream narratives.

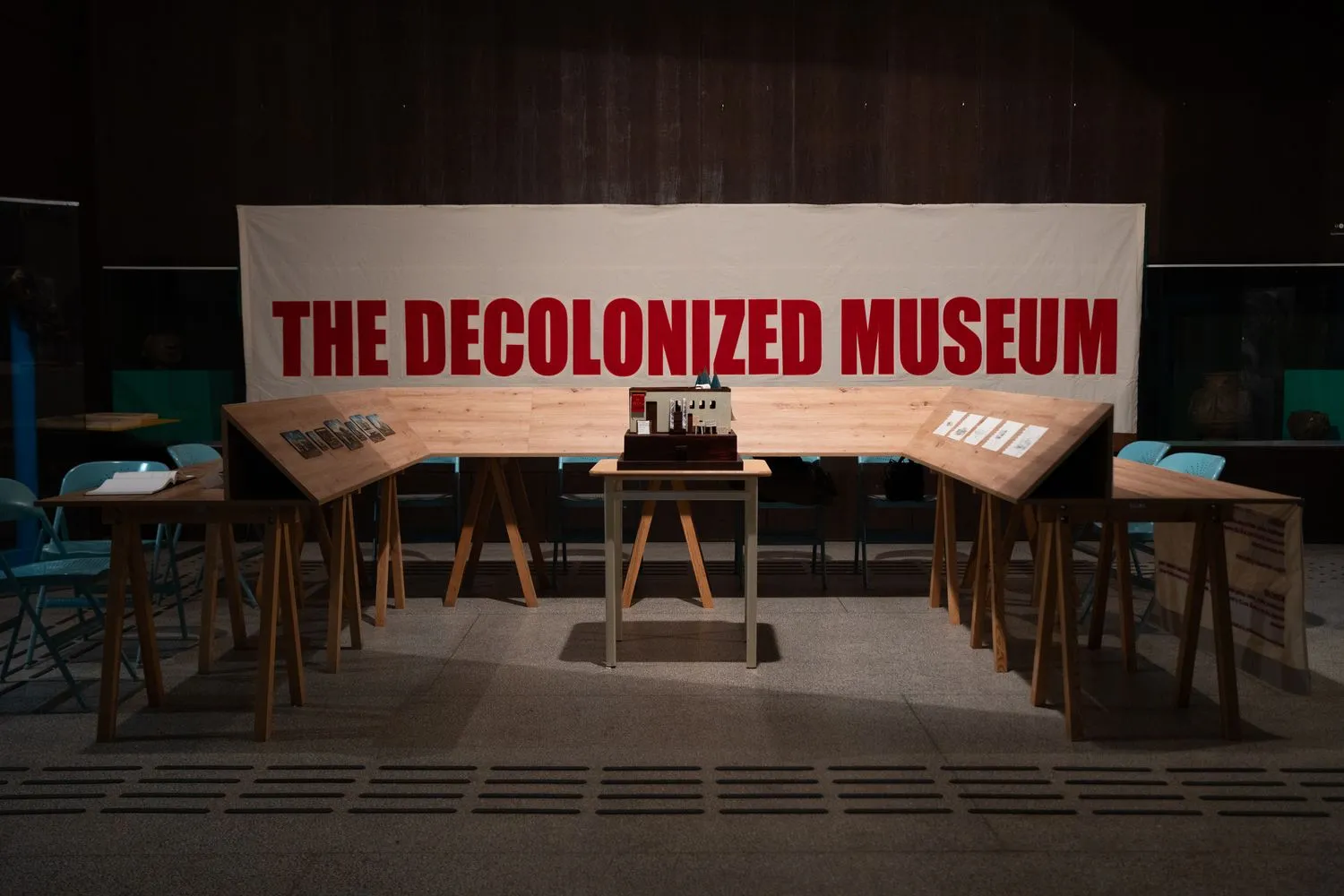

At the 60th October Salon in Belgrade, Ortiz inaugurated the event with her puppet show The root you pulled out is not a hole in my land, it is a tunnel (2024). Drawing from the visual language of traditional children's theater and puppet shows, this tale of resistance unearths buried anti-colonial and anti-imperialist histories of the 20th century, while highlighting Palestine's struggle for freedom. Additionally, she presents a piece from The Decolonized Museum series at the Museum of African Art—an incisive critique of museums as colonial institutions. The series reimagines these spaces as platforms for reparative justice, where looted artifacts are reclaimed, and Indigenous agency and cultural memory are prioritized. By envisioning museums free from exploitative practices, Daniela urges audiences to reconsider these institutions' roles in shaping collective narratives.

Beyond the gallery, Daniela integrates activism and pedagogy into her work, conducting workshops and creating public engagement projects that emphasize collaboration and community-driven approaches. Rejecting the abstraction of systemic issues, she grounds her practice in personal stories and the lived experiences of marginalized communities. Her art is both an act of resistance and a call to action, urging viewers to confront privilege and oppression with clarity and accountability. Daniela will host two workshops in Belgrade on November 28th and 29th, inviting participants to think collectively about decolonization as a revolutionary process.

In this conversation, Daniela delves into the themes of decolonization, cultural representation, and the politics of memory, central to her artistic practice. She reflects on the power of art and grassroots cultural creation in resistance movements, emphasizing her commitment to using art as a tool for political pedagogy. Drawing from her personal journey from Peru to Spain, she discusses how her experiences in Europe deepened her anti-colonial stance, shifting her practice to engage with institutional racism, colonial histories, and the complexities of global power dynamics. The artist also touches on her experiences with censorship in European institutions, particularly regarding her pro-Palestinian stance, as well as the issues surrounding artists' working rights. She argues that museums, by co-opting and neutralizing political activism, reinforce the colonial structures they claim to challenge, proposing a revolutionary approach to cultural production that confronts both colonial legacies and the exploitation of artists.

Jelena Martinovic: I'd like to start with your experience here in Belgrade. You're here for the October Salon, engaging with new audiences. Could you tell me a little about this experience? How has this context influenced your thinking and approach during your time here?

Daniela Ortiz: Actually, it has been really interesting. The contemporary art and cultural industry we are often forced to work in, due to the lack of public resources that are taken up by this very same industry, pushes us to make a living by traveling to different places without always fully understanding the context. Many times, you arrive at a new place for an opening, but you don’t really grasp the local context—politically or culturally.

We were discussing this with some people here, who told me that local artists are also forced to leave to find work elsewhere, and you never get to truly engage with or understand the context of where you are. Many artists come, present their work, attend the opening, and then leave, often without the project being connected to the local context because they don’t understand it.

In this case, I was really lucky. I presented a puppet show here and was determined to do it in Serbian because it’s important for me that the puppets speak the local language. I always try, whenever I present my work, to use the language of the people who will be watching. So, because the puppet show needed to be in Serbian, I asked the October Salon team to connect me with someone who could translate the play politically, not just linguistically, to ensure it made sense in the local context. That was my first step toward engaging with the context here, through this translation process.

I also had the chance to work with local performers—Vladimir (Bjeličić), Andrej (Ostroški), and Zoja (Borovčanin)—who shared the same political views, as well as an understanding of the role of culture in this context, and how the play could resonate here. Although I've only been here for a week, it’s been really fulfilling to not feel completely disconnected from what's happening locally.

Before coming here, I had heard about The Association of Fine Artists of Serbia (ULUS). One of the works I presented was actually intended to be shown here because of ULUS' struggle, not only in terms of their labor rights but also in relation to their space and what that represents.

JM: You’ve recently started incorporating puppetry as a medium to address very complex themes. What inspired this choice, and how do you think it alters the reception of your message?

DO: Well, if you look at my work, I’ve used a variety of mediums and languages. I’m really open because, at least from my perspective, the important thing is to communicate certain political ideas and use art as a tool for political pedagogy. That’s my aim. A few years ago, I started becoming more intentional about using my work to contribute to understanding institutional racism and its relationship with the colonial order. Institutional racism in the European Union, for example, is an extension of colonialism—historically, but also practically—because they are imposing the same systems they’ve historically imposed on the Global South, but now within Europe.

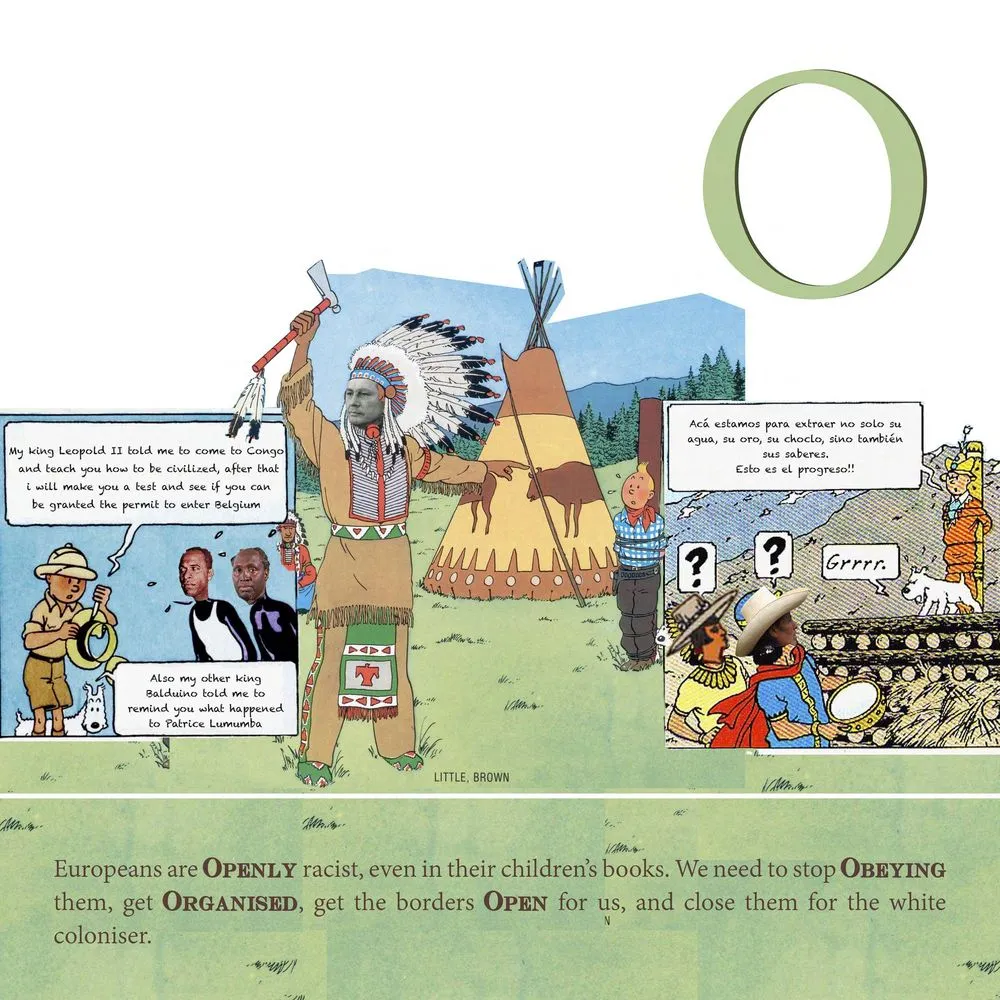

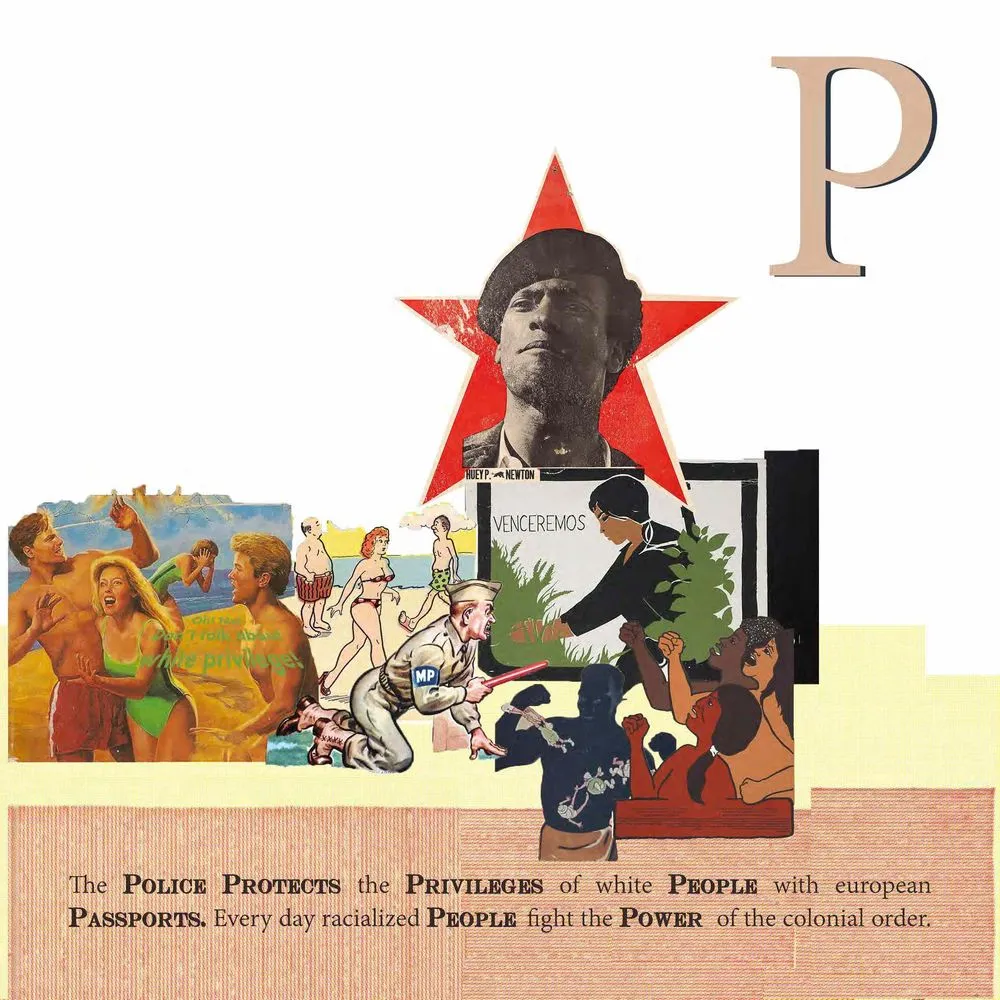

Actually, it was an artist friend who critiqued an older piece of mine. She said, "I find what you're saying really interesting, but I don't like your European aesthetics." She knew I could paint because I started as a painter, and being from the Global South, I’ve always been close to handmade cultural practices that are really useful for pedagogy. So I went back to using collage, starting with digital collages for a book I made called The ABC of Racist Europe. Around the same time, my first son was born, and I started thinking about children's books and their contents. That led me to approach children’s material in a different way, and I returned to creating handmade work.

A few years ago, I was invited to Italy to do a performance, but I didn’t want to use the same language I had been working with. It's not that I don’t appreciate conceptual art—it’s actually quite useful because it uses cheap resources, which I find beautiful. (laughs) At a certain point in my life, when I was working in a chocolate store and doing art projects at the same time inside, conceptual art was a perfect fit. I couldn’t sit there and paint like I can now.

When I was invited to do this performance in Rome, I asked myself, "What is a handmade language for performance?" And I thought of puppets. Some of the people I was working with were unsure about using puppets, but there are amazing references out there, like Bertolt Brecht, who worked with puppetry for years in political art. I also admire Yuyachkani, a popular theater company from Peru, which has done incredible political work. There are many artists who use puppetry in a powerful way.

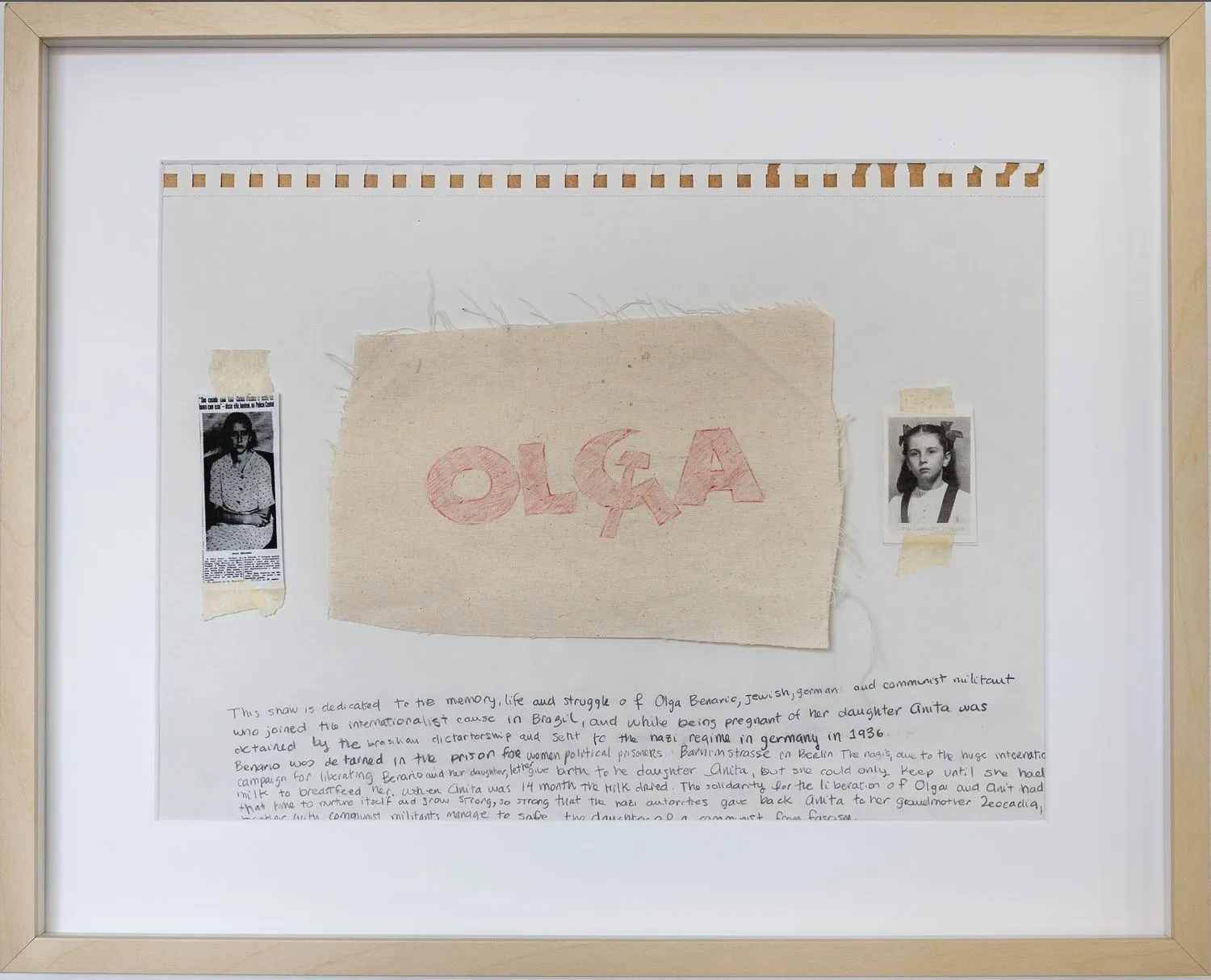

So I created my first puppet play, Il Suono della Lupa, in Italian, to denounce the removal of migrant children from their families. The play also explores how these institutional racist policies are, on the one hand, extensions of colonial violence against racialized, Global South mothers, families, and children. On the other hand, it reflects on the policies enacted during the Fascist period under Mussolini, such as the Opera Nazionale per la Maternità e l’Infanzia, an institution created to shape motherhood and childhood in the context of state control. This history intersects with the present in ways that I wanted to explore through puppetry.

JM: I loved the puppet show you presented in front of the Cvijeta Pavilion, which officially opened the October Salon. Can you tell me about this particular work and how it reflects the complexities of colonial histories and the resilience of the communities involved?

DO: This piece was originally supposed to be presented in Barcelona, where I'm going today, and I'll be showing it on the 20th of November—the day Franco died, actually. It’s been really special to present it here on the 20th of October, the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Belgrade. Through some magical anti-fascist twist of fate, I’ll be presenting it in Barcelona a month later. (laughs)

The piece is meant to question the concept of terrorism. I believe we need to open up a political conversation about all the policies and laws that have been imposed since the late 1970s, which have been used to persecute not only those connected to military resistance but also those aligned with certain ideological frameworks. In Peru, for example, anti-terrorist laws are so broadly applied that people can face extreme punishment for merely being tangentially associated with these frameworks. The punishment can even extend to being killed.

Take Guantanamo, for instance, or political prisoners in Peru like Víctor Polay Campos, who has been in prison for more than 30 years and spends 23 hours a day in a cell without ever going outside. He’s in a military prison, a space that exists outside of any legal framework. We also see this with Carmen Villalba in Paraguay, or political prisoners in Chile who have been incarcerated for trying to kill Pinochet. What kind of democracy are we talking about when people who dedicated their life to fighting dictatorships, that killed and disappeared thousands—like Víctor Jara, who had his hands cut off and was murdered in a stadium—are still in prison across Latin America?

So the main issue I wanted to address was this political context. I’ve also done another piece recently called Tirador Blanco, which is a shooting game that targets arms companies. In the game, you shoot their products and logos, though I originally wanted to include the CEOs. (laughs) However, the people I worked with advised me not to, so I don't end up in jail. (laughs)

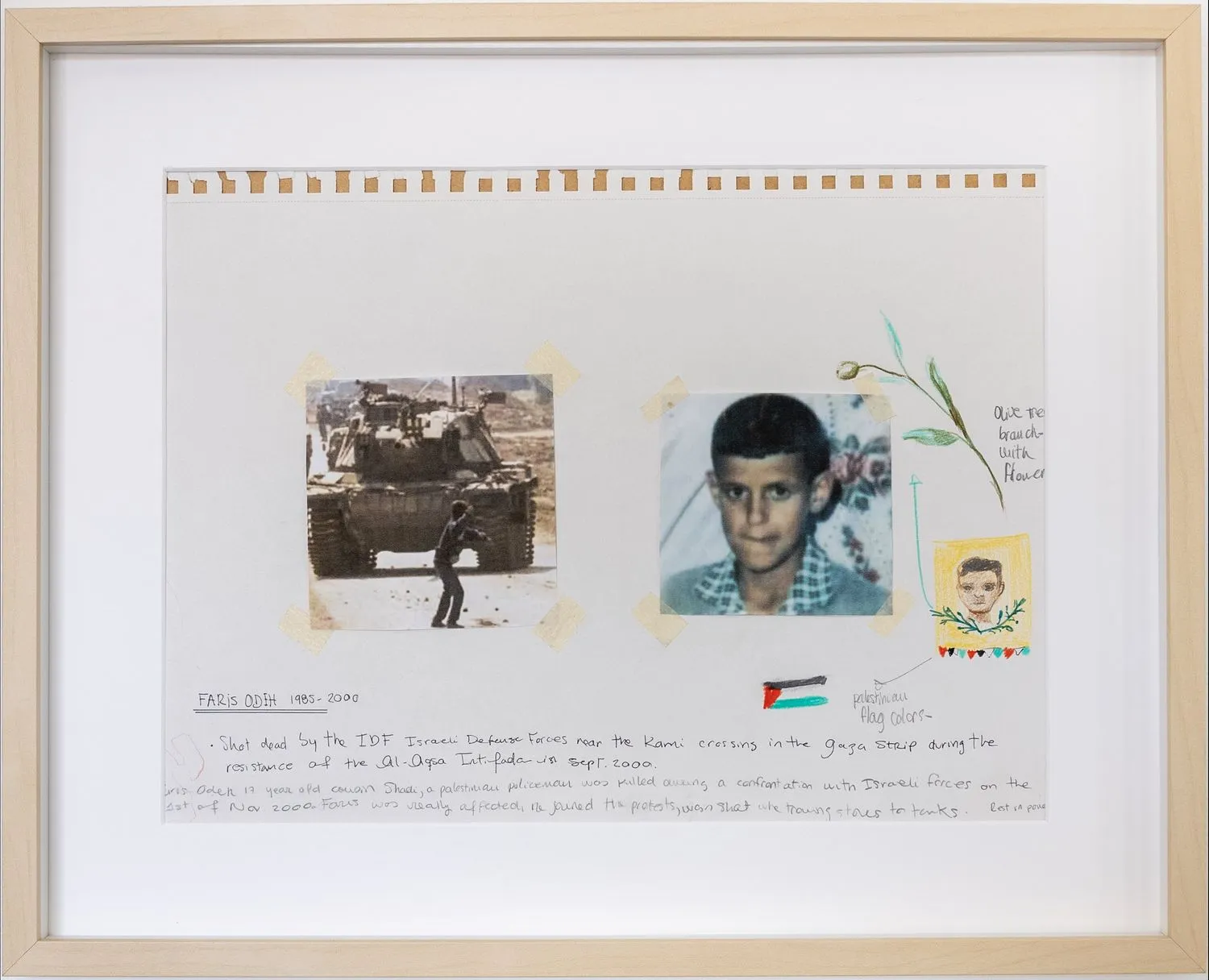

What was also important for me was to challenge this flat narrative around pacifism—a narrative that has enabled and empowered the ongoing violence of colonialism, fascism, imperialism, and Zionism. The level of violence has become absolutely brutal, as we are seeing right now in Palestine. I decided to address all the people who have been imprisoned and disappeared since the late '70s in the Global South, as well as those historically resisting in tunnels, like in Vietnam and Gaza. These struggles share a common history, strategies, and perspectives regarding persecution. Initially, I wanted the piece to be in solidarity with Palestine, but then I realized it had to be about Palestine, because I believe that right now, any tool we have—whether it’s art or activism—must be used to explain, denounce, and understand what’s happening there, and to support the struggle.

JM: In your series The Decolonized Museum, you critique how museums uphold these colonial legacies, while constructing narratives of power, privilege, and representation. What initially inspired this project, and how has your approach evolved over time?

DO: The inspiration came from the censorship I faced—actually, several instances of censorship in Germany. Recently, I’ve worked with institutions like the Ludwig Museum and the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn. One of the worst experiences occurred when I was invited to participate in a show about racism and migration at the Bundeskunsthalle with a work titled The ABC of Racist Europe. A far-right Zionist group targeted the museum, accusing me of antisemitism because of my pro-Palestinian stance. This is something they’ve been doing everywhere.

The museum told me they wouldn’t remove my work, but they put a sign next to it, accusing me and my work of antisemitism—without even informing me. They wrote an explanation next to my work, essentially curating in line with Zionist and imperialist views. They also organized talks in German about my work without involving me, and I started receiving threats via email. It was an extremely hostile atmosphere.

Before that, I had a similar situation with the Ludwig Museum. I was part of an exhibition about anti-colonialism, and the same far-right group targeted me because I had created a small piece in solidarity with censored documentaries at Documenta. All this targeting began, and the Ludwig Museum, which had expressed interest in acquiring my work, suddenly backed out, accusing me of antisemitism.

At one point, they even had a curator review all of my work to find supposed signs of antisemitism. They looked at my pieces critiquing companies like G4S, which is part of the prison system in Israel where Palestinian political prisoners are tortured and killed. That alone was enough for them to accuse me of antisemitism. I told them they should at least give me a formal explanation so I could defend myself. Instead, they chose to punish me economically by withdrawing the acquisition while still keeping my work in the exhibition.

What’s happening is that these institutions are profiting from decolonial aesthetics and epistemologies while censoring us when we address issues like Palestine or workers’ rights. They exploit artists from the Global South, who often lack labor protections, and take advantage of our precarious situations. Working in Europe is often economically better than in Peru, due to the colonial economic system, but they’re using our voices while silencing us politically.

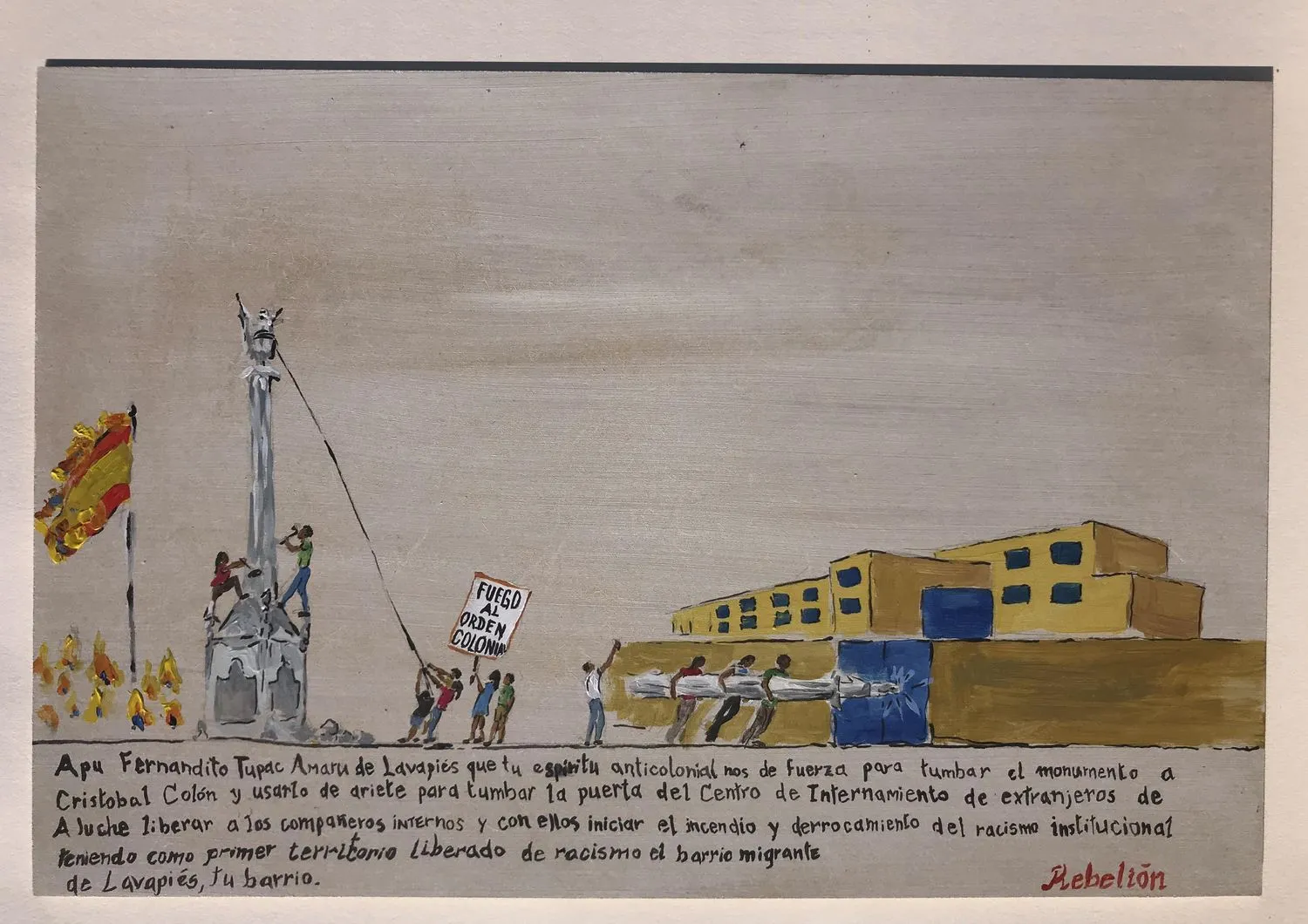

The Decolonized Museum is both a series of paintings and a scale model for what a truly decolonized museum would look like. Decolonization is not an exhibition or a program in a white European museum—it’s a revolutionary process that must take place across whole society before it happens in a museum. Museums, by continuing to co-opt and neutralize political activism, are reinforcing the same colonial structures they claim to challenge.

JM: The piece from this series on view at the Museum of African Art in Belgrade includes a scale model museum and references art institutions in Bonn, but also touches on local struggles here in Belgrade. Can you share more about these references and the significance of having this physical representation of an institution?

DO: On one hand, I think there are fewer and fewer spaces for cultural struggles, especially when it comes to artists’ working rights. The bourgeois narrative around artists—who often aren’t bourgeois and don’t have money—has overshadowed important conversations about our rights and resources as workers. We have both political and social responsibilities in society. For instance, I don't fully agree with artists who use public funds to make work that isn’t directed toward the working classes who fund that work through their labor. Public funds don’t come from the state; they come from the working class, so we have a responsibility there.

When it comes to the local context here in Belgrade, I was aware of the struggles regarding ULUS and cultural spaces in general and the debates surrounding them. It connects deeply to the normalization of censorship. For example, pro-Palestinian artists in the Global North can be censored without consequences for the institutions. Museums can work with you for months, and then censor you, and refuse to pay, and there’s often nowhere to turn because many artists don’t even have contracts. This is just one part of the exploitation happening to cultural workers and artists.

There’s a stark class difference in Europe, too. Museum directors who talk about decolonizing museums earn €9,000 to €10,000 a month, with all their expenses covered, while artists are paid €300 to €500 for their contributions. And without our work, these museums wouldn’t exist. This exploitation extends to shaping ideologies and careers. These directors decide who gets to work based on political or ideological convenience, creating a precarious system that affects what artists can or cannot say. And without our work, the museums wouldn't exist.

Many artists in the Global South, who talk about decolonization, avoid solidarity with Palestine to protect their careers. For instance, at the Venice Biennale, which is all about decolonization this year, there was a call from the Anga Art Alliance Against Genocide to close the Israeli pavilion, yet many decolonial artists didn’t sign the letter. They knew what was happening but chose to stay silent, using decolonial aesthetics to mask European complicity.

And even in events like the Venice Biennale, which is one of the largest in the art world, no one gets paid. I didn’t even receive €100 for showing a work. Artists with entire pavilions don’t get paid, and they often have to find their own resources to participate. So, we legitimize a system of exploitation by giving them political power to continue exploiting and silencing us.

I return soon to Belgrade to hold a workshop discussing these issues—how we can resist and change this system. We have historical examples, like Frida Kahlo, who has been depoliticized by the neoliberal cultural industry, but she was a militant communist, part of an artist union, and her work had a deep political dimension. It's not just about content of the work; it's the structure we work in and the role we play in the change we want to see. We don’t want to support this system of exploitation anymore.

JM: The installation includes the concept of the Popular Committee for Cultures to challenge traditional Western cultural institutions. How does this institution function within your practice, and what role does it play in envisioning decolonized cultural production?

DO: It's a reference to Venezuela, particularly the Ministry of Popular Power for Culture, which I’ve worked with. I was invited to paint a mural outside Hugo Chávez’s room, which was a great honor, especially on October 12th. This invitation came after I wrote an open letter to the Reina Sofia Museum in Spain, asking them to remove my work from an exhibition. During the NATO summit, the wives of NATO leaders and the Queen of Spain took an official photograph against the backdrop of Picasso's Guernica. Considering Picasso was a Republican and communist militant, I found this act to be a form of political appropriation. Although I made the request, it wasn’t widely covered or discussed in Spain’s cultural context.

That invitation to Venezuela was meaningful to me, and I'm glad to have reconnected with Latin America, particularly in the last four years. What I’ve noticed, especially in contrast with Europe, is that there’s a sense of hope in places like Venezuela and Bolivia—people are actually creating the changes they want to see. Despite the blockades, sanctions, economic warfare, and constant media attacks against Venezuela, they have built a new notion of culture. Bolivia, for example, has a Ministry of Decolonization. Being from Peru, I can see the contrast: while in Peru, indigenous identity is commodified and used to sell products by industries that oppress indigenous people, in Bolivia, there’s been a real anti-colonial process. Indigenous people there aren’t just given human rights—they are political subjects who actively participate in decisions about the country's future.

The same goes for Venezuela, Cuba, and even Brazil with movements like the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra (MST), where culture plays a critical role. Culture is as important as any other aspect of political organization—it’s used as a tool for political pedagogy. For example, we're talking about abortion rights in Latin America, and it's an important conversation since abortion in Peru is illegal. But Cuba has these rights implemented since the 1960s; why don't we look up to this model? In Cuba, for instance, while some progressives criticize the country, they ignore the advances that have been made. During COVID-19, Cuba passed the Families Code, which allows diverse families, including LGBTQ+ families, to adopt. They’ve also abolished patriarchal systems that place mothers under the control of biological fathers. These countries provide valuable references that we should learn from. In terms of decolonized cultural production, the examples are already there. These processes are happening in real-time, and culture plays a central role in them.

JM: Now you’re back to Peru, but you've been living in Spain for 13 years. How has your experience in Spain affected your practice and your perspective?

DO: Well, I got deeply radicalized to be anti-colonial. (laughs) When I moved to Spain in 2007, it was my first time in Europe, and I had all these images of Europe as this superior place, one that doesn’t even admit to being racist. The idea was that racism was something for Latin Americans or others, but not Europeans. It was a shock to experience racism myself. In Peru, as someone considered white or mixed race, I had racial privilege. But in Spain, I saw that the privilege of being a student in the country didn’t protect me from racism, especially institutional racism.

The immigration system there was like going on trial against the Spanish state just to get permission to stay. And on top of my experience, I witnessed the persecution, detention, deportation, and even murder of migrants. Spain has seen over 40,000 people die at its borders since implementing its immigration law. Seeing that violence firsthand, and understanding it as a continuation of colonialism, made it clear that this system of exploitation maintains oppression in the Global South.

I started joining political organizations, like the campaign against immigrant detention centers. There was even a squatted building for illegalized migrants, especially when Spain removed access to healthcare for them as part of healthcare privatization. Spain used to have universal healthcare, but they began targeting the most vulnerable. It was eye-opening to see Europe’s cruelty and lack of care, and it helped me understand the depth of the exploitation happening in the Global South too.

To put it bluntly, they don’t care. And some, like the Germans, even have a word for enjoying another’s suffering—Schadenfreude. This mindset has become part of the hegemonic culture in Europe. You see it when they debate the situation in Palestine. Seeing that evil so clearly has been a real education for me, as well as how the so-called progressive left and white imperialist feminism collaborates with this system. It’s been a process of realizing that both Europe and the United States are enemies in this struggle.

JM: We've been seeing a lot of censorship lately in the art world. In light of this, how do you see the role of art in addressing colonial struggles and challenging entrenched norms? And also, what do you think the role of institutions should be?

DO: Yes, I think it's important to distinguish between making art and organizing exhibitions. Exhibitions often depend on public resources that, in many contexts, are controlled by people who manage them as if they were private assets, aligned with their own political and economic agendas. But art? People make art, people create culture. When I think about the solidarity we're seeing with Palestine right now—the amount of images, songs, poems, and posters being created to denounce genocide—it really moves me. This response, this cultural outpouring, is something that no amount of money, no institution, no Zionist or imperialist force could ever match. It’s this grassroots response where you see the true spirit of culture.

Some of these creators are professional artists, using their tools in more refined ways. But a lot of it is just everyday people using cultural tools to make their voices heard. Even though it’s a difficult time, there’s so much hope coming from Palestine. Culture is being reclaimed for resistance, not for the elite or bourgeoisie or as a commodity. That’s where I see the power of culture right now.

As for institutions, yes, some people within them are trying to push this forward. I’ve worked with institutions, as you probably have too, and we’re often forced to engage with them because, realistically, it's hard to make a living doing this otherwise. Many of us have done other jobs just to keep going, but we’re always caught in this struggle to access more resources in order to support a culture that’s anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, and for the people. We want culture to serve as pedagogy, for it to be something for everyone, not just for the elites in New York or London.

I do see some people inside institutions trying to subvert these structures from within, but most of the institutions I’ve worked with, especially in Europe, feel dead. They have so many resources, but they’re focused on making propaganda rather than culture. They kill art in museums. People feel stupid when they visit museums because the art is presented in ways that alienate them. I feel that way too sometimes, and then I realize there was nothing to understand to begin with as noone even tried to explain it. (laughs) It’s not that the work itself is difficult, but rather, the way it’s communicated makes it impossible to connect with.

I’m not saying we need to make everything simple. We need to experiment with language and abstraction. People understand complex and abstract things. For example, the red triangle—an upside-down symbol that has come to represent resistance in Palestine—is an abstract symbol, but it's been embraced by people as a powerful representation. Now, Germany wants to ban this symbol. Imagine, they want to ban a triangle. (laughs)

And seeing all these songs, paintings, and performances emerge in solidarity with Palestine—like the beautiful performance by a Mexican artist I saw recently—it’s clear that Zionist campaigns can’t touch that. Culture has this transformative power, and that’s where real change happens, not in the elite-controlled institutions.

JM: You actually use workshops and interactive projects to engage communities and foster dialogue. How do these connections you create shape your practice?

DO: I’ve learned that, as artists, we should be of service—whether it’s to a revolutionary process or to the communities we engage with, especially when we’re being funded by public resources. Workshops, in particular, have been crucial for me in understanding how people approach images. I miss that aspect of my practice now that I’m living in the countryside, where organizing workshops isn’t as easy, and in Peru, there aren’t many resources for this kind of work either, so you often have to provide your own.

In Barcelona, I had the opportunity to work with schools and adolescents, which I really enjoyed. It was interesting to learn from their perspective, especially how they engage with images and political issues. It’s in these spaces, like workshops, where you can experiment with how to trigger discussions, especially in contexts where political conversation isn’t the norm. The strategies we develop in these settings are invaluable for applying in other, more challenging contexts later on.

I really appreciate this exchange, as I learn a lot from them. Economically speaking, though, it’s tough. The economic pressure on artists right now is overwhelming. It's difficult to balance being an artist and a teacher, for example, because the level of exploitation we’re dealing with forces you to choose one or the other—or juggle an impossible number of roles.

I love creating, but I don’t always want to be forced into making exhibitions to survive. I’d love the freedom to create without the constant pressure of the cultural industry’s production machine. There’s value in spaces that allow you to focus on art and culture without the weight of exhibition expectations. The true essence of creation lies, for me, beyond the cultural machinery.

JM: To wrap it up, how do you envision a museum from a decolonial perspective, and do you think museums can ever be fully decolonized?

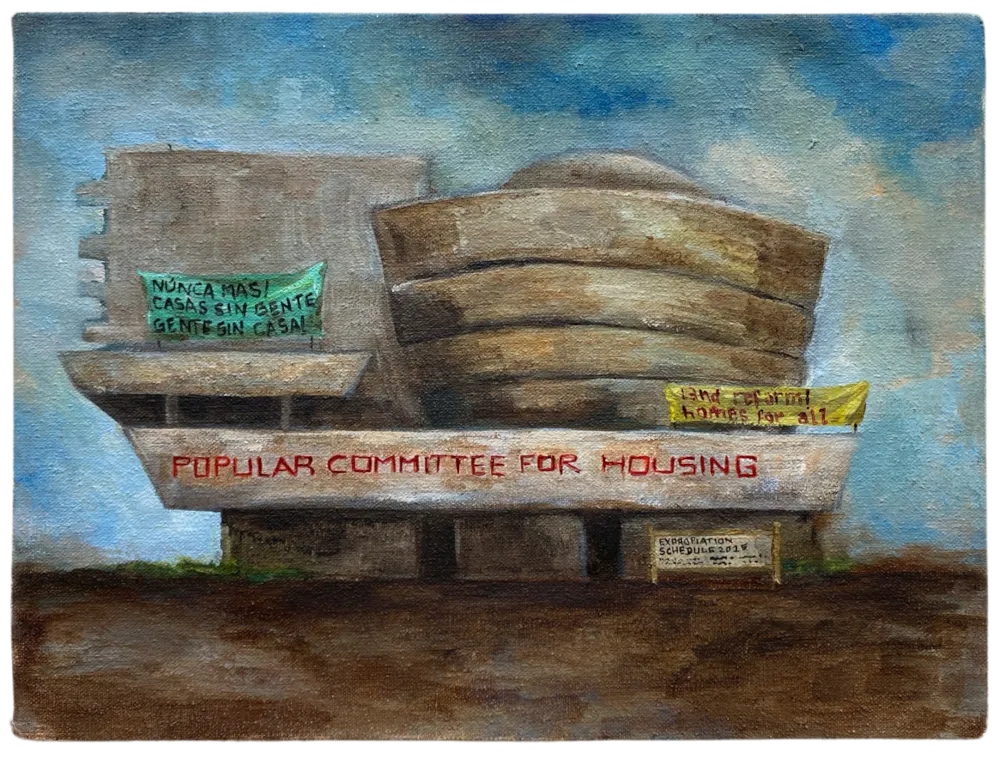

DO: Well, for example, take MoMA—we could burn it. (laughs) One of my paintings actually shows MoMA in flames. I do believe some places should be symbolically burned. Institutions like MoMA and the Guggenheim have had such close relationships with entities like the CIA. Who are these people even representing? We don’t need them. We could scatter their ashes far away, symbolically getting rid of these colonial institutions.

In my paintings, I envision museums being repurposed. The Guggenheim, for instance, has played a huge role in gentrification. Instead of being a museum or a cultural center, I imagine it as a "Popular Ministry of Housing," where it gives back to society what it has taken—because gentrification is a form of cultural theft, robbing people of housing through inflated rents.

Then there’s the Ludwig Museum. I painted it as a prison. We need a place to hold accountable those who have participated in genocide—politicians, arms dealers, lobbyists, soldiers from the IDF and the U.S. They could all be put in there, because we’re going to need space for that.

But beyond the radical, there’s also the possibility of creating cultural spaces with a constant presence of artists—places where artists can come and go freely, spaces not tied to career success or money. These public cultural spaces would be places where we organize to develop our work collectively.

For instance, when I lived in Jordan, I got to understand the Palestinian struggle much better, as there is a significant population of Palestinians in the country. There, I visited Darat al Funun, which has one of the most powerful collections of Palestinian art. It’s a space of pure resistance. They just hosted an exhibition condemning the genocide in Gaza. That’s what a decolonized museum looks like—it already exists in places like Darat al Funun or in Venezuela and Bolivia, where cultural institutions actively challenge imperialist structures.