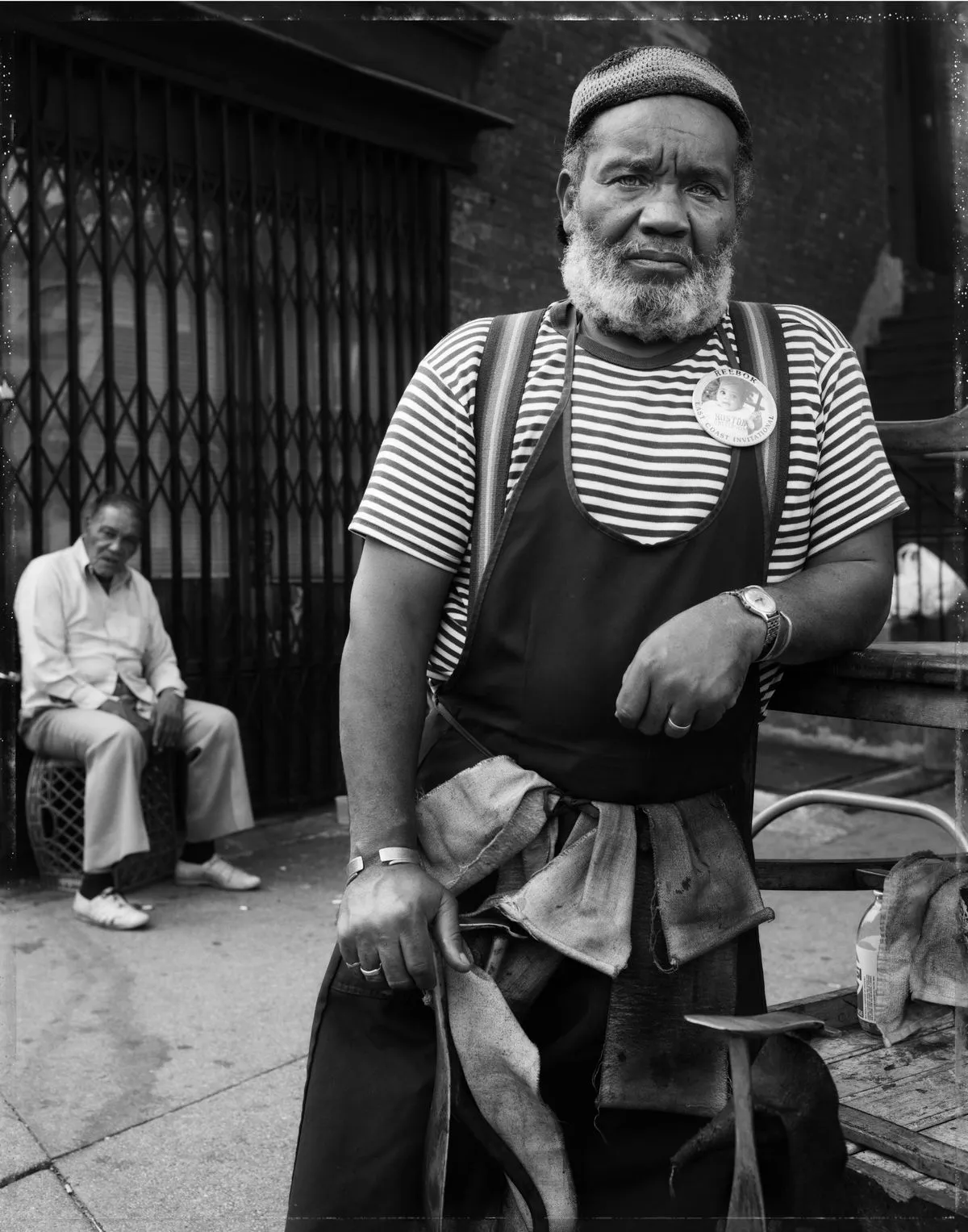

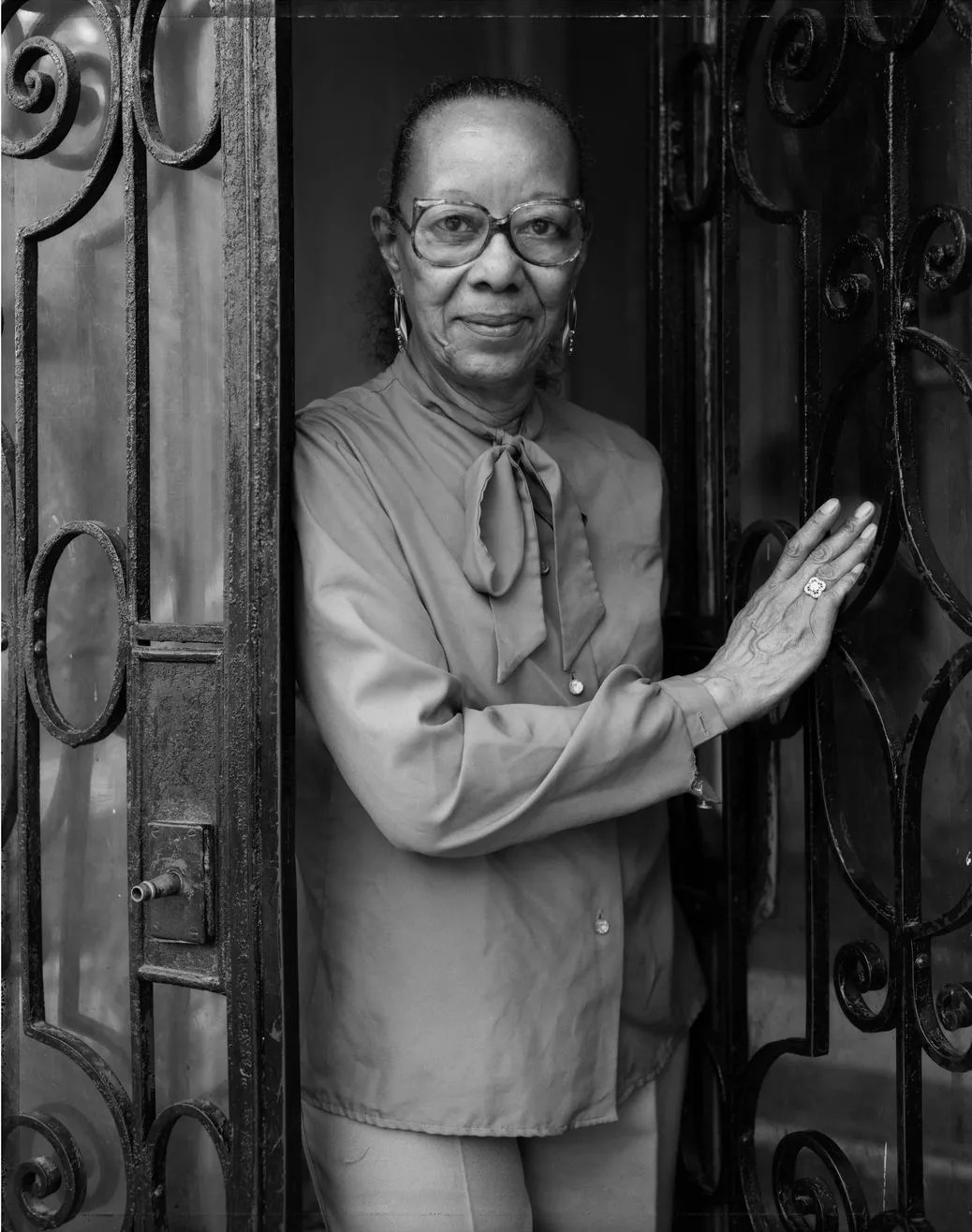

Dawoud Bey, A Woman at Fulton Street and Washington Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, from the series Street Portraits, 1988. Pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago. © Dawoud Bey

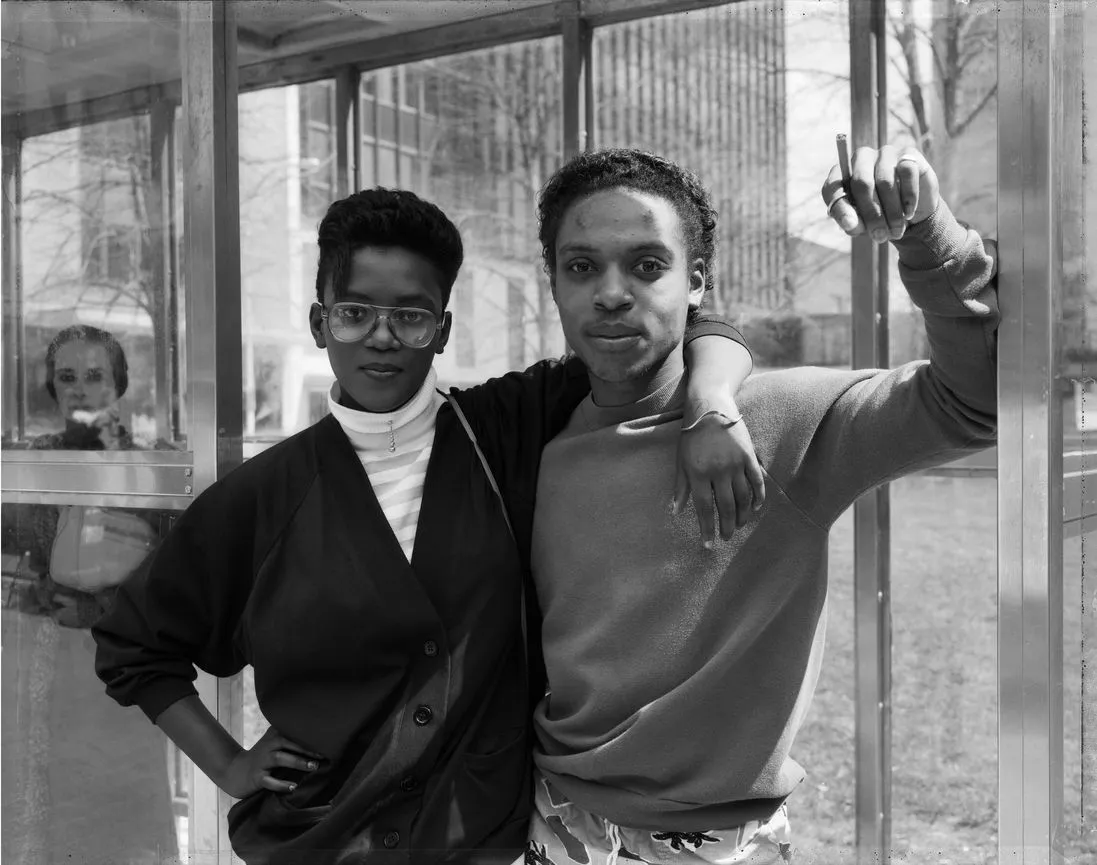

Dawoud Bey, A Woman at Fulton Street and Washington Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, from the series Street Portraits, 1988. Pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago. © Dawoud Bey For nearly five decades, Dawoud Bey has used photography to engage deeply with Black communities, history, and representation. From Harlem, USA (1975–1979) to Street Portraits (1988–1991) and beyond, his work foregrounds collaboration, presence, and the dignity of his subjects. His portraits—often made with a large-format camera and a deliberative process—offer a counterpoint to fleeting, surface-level depictions of Black life in American cities.

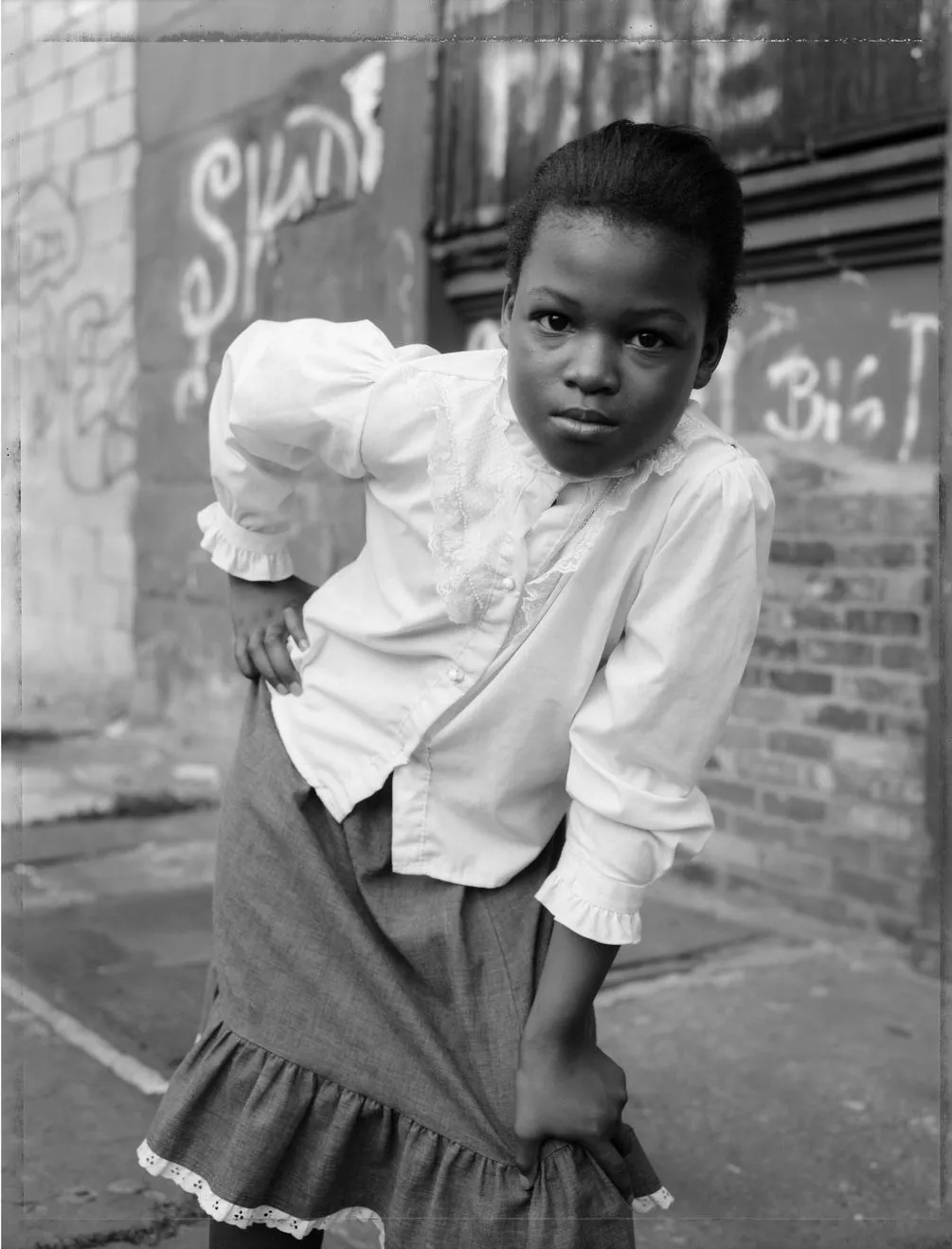

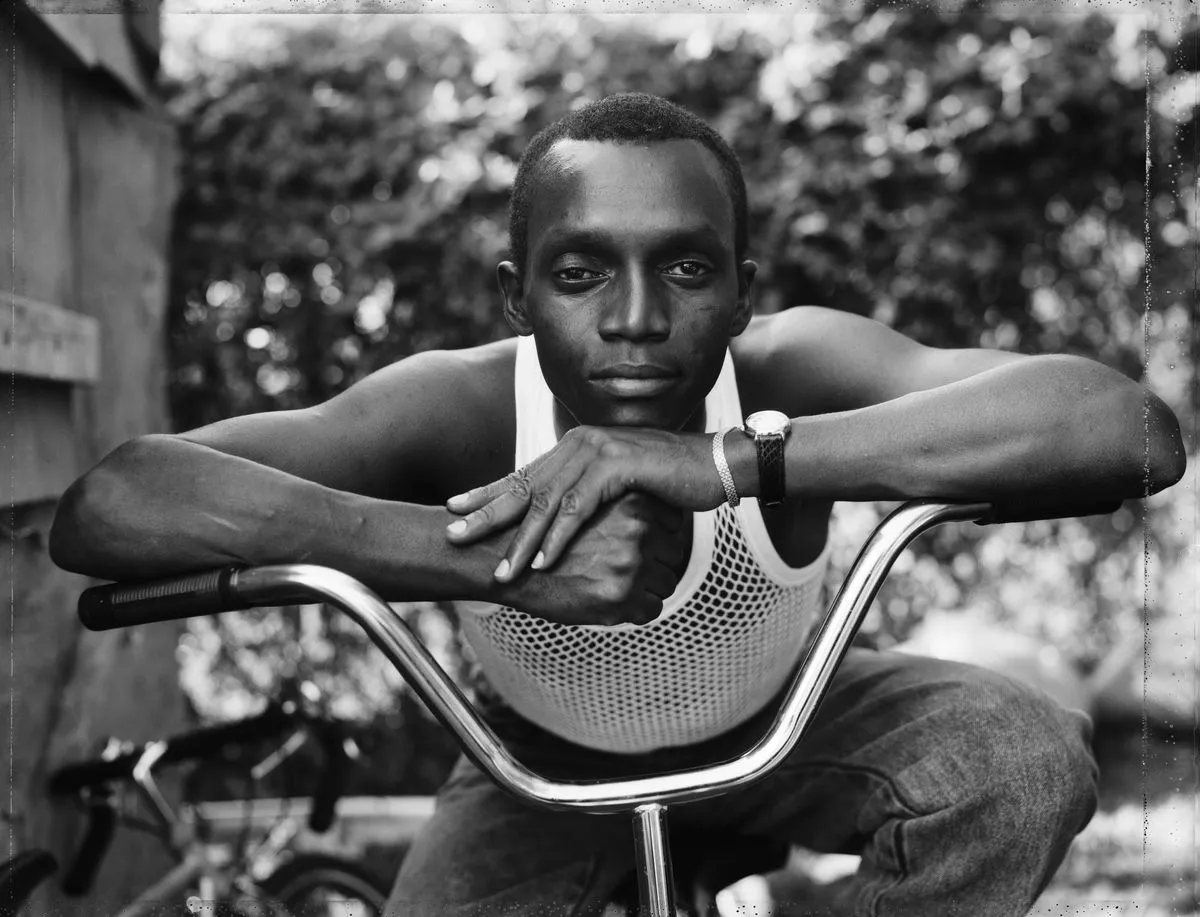

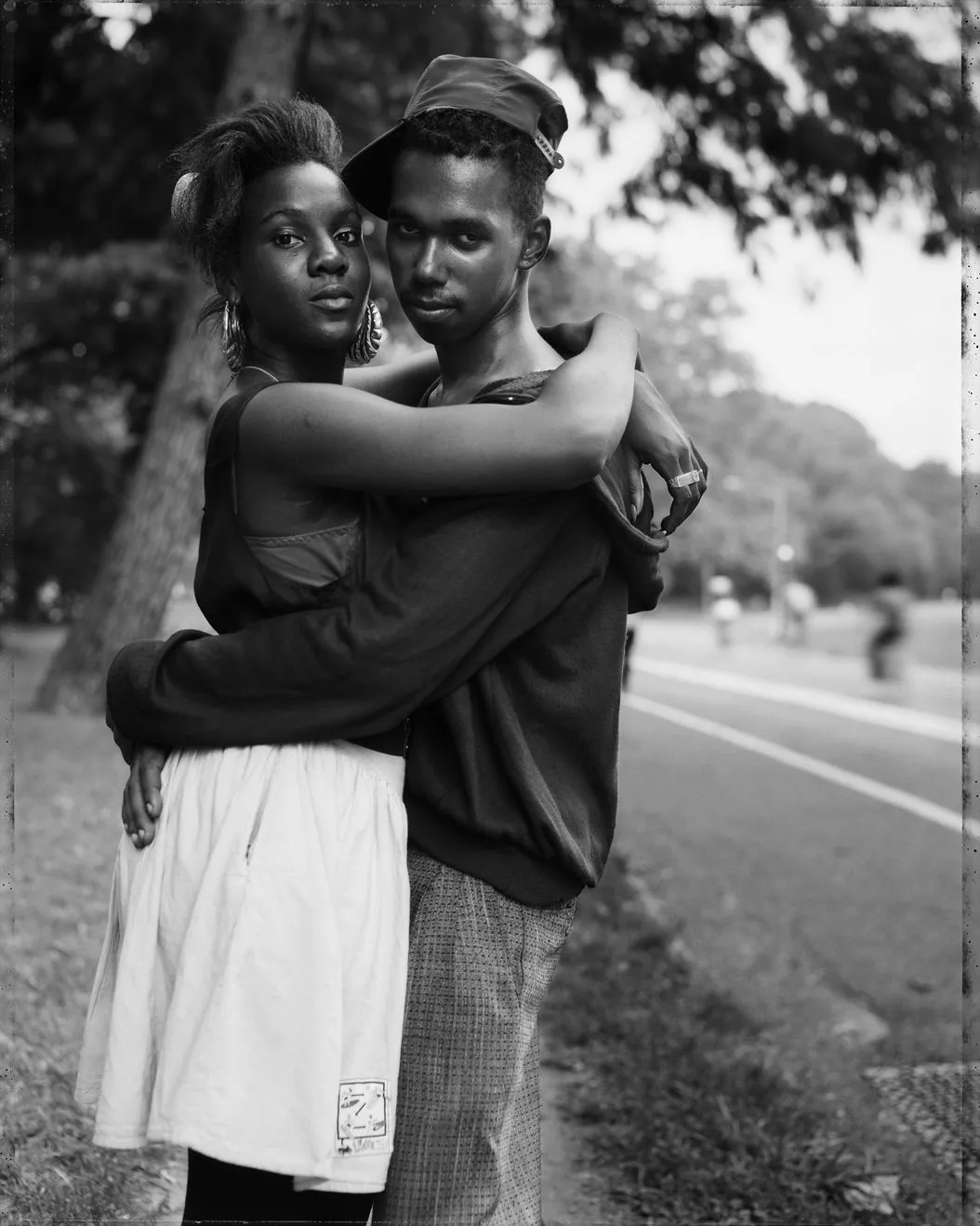

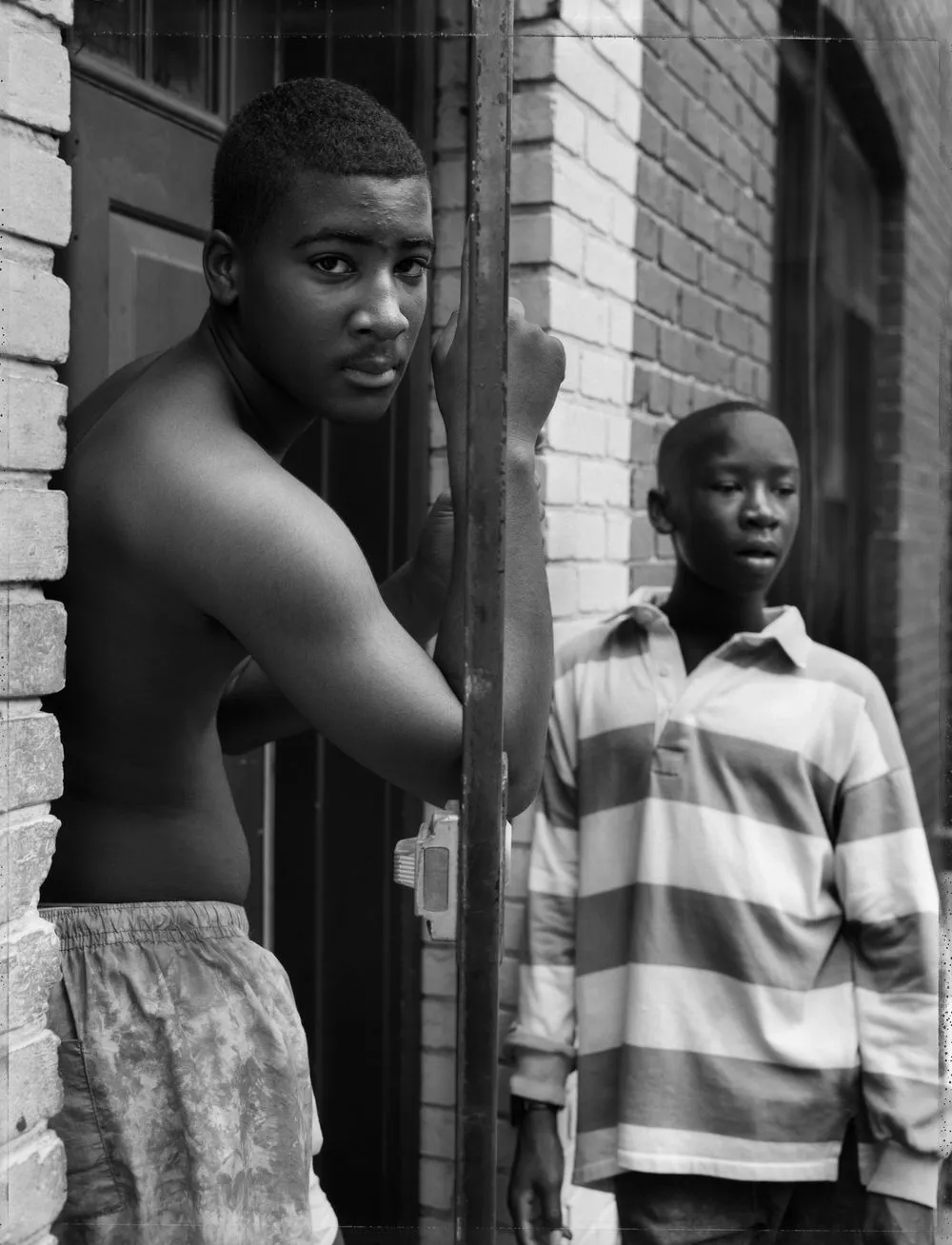

Bey's practice is rooted in an ethical approach to portraiture, challenging traditional hierarchies in photographic representation. By fostering collaboration, he reframes photography as an act of political and social responsibility—one that insists on visibility, agency, and historical consciousness. His images do more than document individuals; they weave personal narratives into the broader fabric of American history and culture, illuminating stories that have often been overlooked.

Currently on view at the Denver Art Museum, Dawoud Bey: Street Portraits presents 37 images from this pivotal series, marking the first standalone museum exhibition dedicated to this body of work. Created between 1988 and 1991, these portraits capture Black Americans of all ages in cities across the U.S., situating them within their everyday environments while allowing space for self-presentation. Using a tripod-mounted large-format camera and Polaroid positive/negative film, Bey not only achieved a richly detailed image but also established a reciprocal relationship with his subjects—offering them an instant print as a gesture of shared authorship.

In this conversation, Bey reflects on the formative influence of New York's cultural and political landscape, the evolution of his photographic approach, and the ways in which portraiture can assert presence and interiority. Through his lens, photography becomes not just a record of time and place but a dialogue—one that continues to resonate today.

Jelena Martinovic: You came of age in New York City during a vibrant and turbulent period marked by social and cultural upheaval. Could you share what the city—and particularly your neighborhood of Queens—was like at that time, and how it influenced your early photographic practice and your broader ideas about photography?

Dawoud Bey: When I was living in Queens I was initially mostly engaged with the music community, as I was a young drummer, playing with a number of different local bands. I also started going to the Studio Museum in Harlem during that time in the mid-1970s, and it was that institution and others—like Just Above Midtown Gallery—that began to introduce me to a community of Black artists and photographers who became my community.

JM: Harlem, USA captures the vitality of a historically rich and culturally significant community. What drew you to Harlem as a subject, and how did you navigate representing its layered African American experience?

DB: My parents had lived in Harlem before I was born. It's where they met. Though we were living in Queens when I was born, we had a number of family friends and relatives who still lived in Harlem, so we'd visit frequently. Harlem, USA was a way for me to reconnect to the place where my personal narrative begins, with the meeting of my mother and father, and also to make work that contributed to the history of Harlem's visual representation. It allowed me to wed my nascent art practice to both my personal narrative and a broader sociocultural history.

JM: The Street Portraits series marks a shift toward a more intimate, collaborative process with individuals, using a tripod camera and a slower approach. What led to this change in your practice?

DB: When I began that work I wanted to find a way of working that was more reciprocal and more dialogical. I wanted to address the hierarchy that exists in making photographs of individuals, particularly Black subjects—that tend to privilege the photographer. Along with using a large format camera mounted on a tripod, a very important part of this shift was in using a 4X5 Polaroid positive/negative film that allowed me to make both a negative and an instant print after photographing someone. I gave the print to the individual and kept the negative to make large exhibition prints. It allowed the subjects to be in possession of their image.

JM: These portraits emerge from a collaborative process where your subjects had the opportunity for self-presentation and performance in their urban environments. Could you elaborate on how this collaboration unfolded, and how the use of a tripod camera and Polaroid film influenced this dynamic?

DB: The use of the tripod and large format camera added a kind of ceremonial air to the situation; creating a kind of public "studio of the streets." It both allowed for a more sustained—though momentary—engagement while also making for a very different kind of photograph materially, one that holds a lot more information in the large format negatives, making for a more richly descriptive photographic print. A print made from a large format negative is fundamentally different from one made with a small 35mm camera and film.

JM: There's a palpable strength and depth in the way your subjects look back at the viewer. How do you see this interaction shaping the way they assert their presence?

DB: My directing of the subjects was a way of allowing them to direct their gaze at the world through the camera, and also describing them with a rich degree of interiority and self-presence.

JM: Your photographs vividly capture not only the presence and dignity of these individuals but also the broader cultural moment they inhabit. How do you see your work as a reflection of the time and place in which these portraits were created, and how do you approach capturing the essence of culture and history through your subjects?

DB: Well, the geography of the streets in the communities in which I photographed them became the context and kept them anchored in a specific place while also being part of a representation of Black urban communities at that time. These photographs were made at the height of the crack epidemic, and yet there were still Black people in those communities carrying on with their lives. These portraits describe them in the act of living.

JM: Your images reveal the interiority of your subjects, going beyond surface-level representations. How do you approach capturing this depth in a way that encourages viewers to connect with the humanity of those in your photographs?

DB: The photographs were a way of creating a conversation between the human community, one in which people might find some common human ground between themselves and people who might be in some way presumably different from them. For Black people and viewers of the work in a museum or gallery context, the work becomes a kind of profound self affirmation.

JM: Throughout your career, you’ve worked to reshape the representation of Black American subjects and communities while amplifying their experiences. How has your approach evolved over time?

DB: My current work deals with the unseen but very real presence of African Americans embedded in the American landscape. Though they are not visible in the photographs they are very much the subject of this work.

JM: Decades later, how do you view the ongoing challenges of accessibility and representation in the global art world?

DB: I think the art world has expanded considerably in the past few decades regarding the issue of a broader culture of representation. That follows decades of struggles and decades of work on the part of curators and art historians of color and those institutions with increasingly progressive and inclusive leadership.

JM: How do you see the role of artists in addressing issues of race and visibility, and what responsibility do institutions have in this process?

DB: Artists are always free to pursue whatever agendas they want through their work; that's the embodiment of freedom itself. Institutions can play a significant role in amplifying the work that artists of color are doing, and giving that work a place in the art historical conversation that doesn't pigeon hole artists of color, but acknowledges their broader contribution to a broad range of art practices.