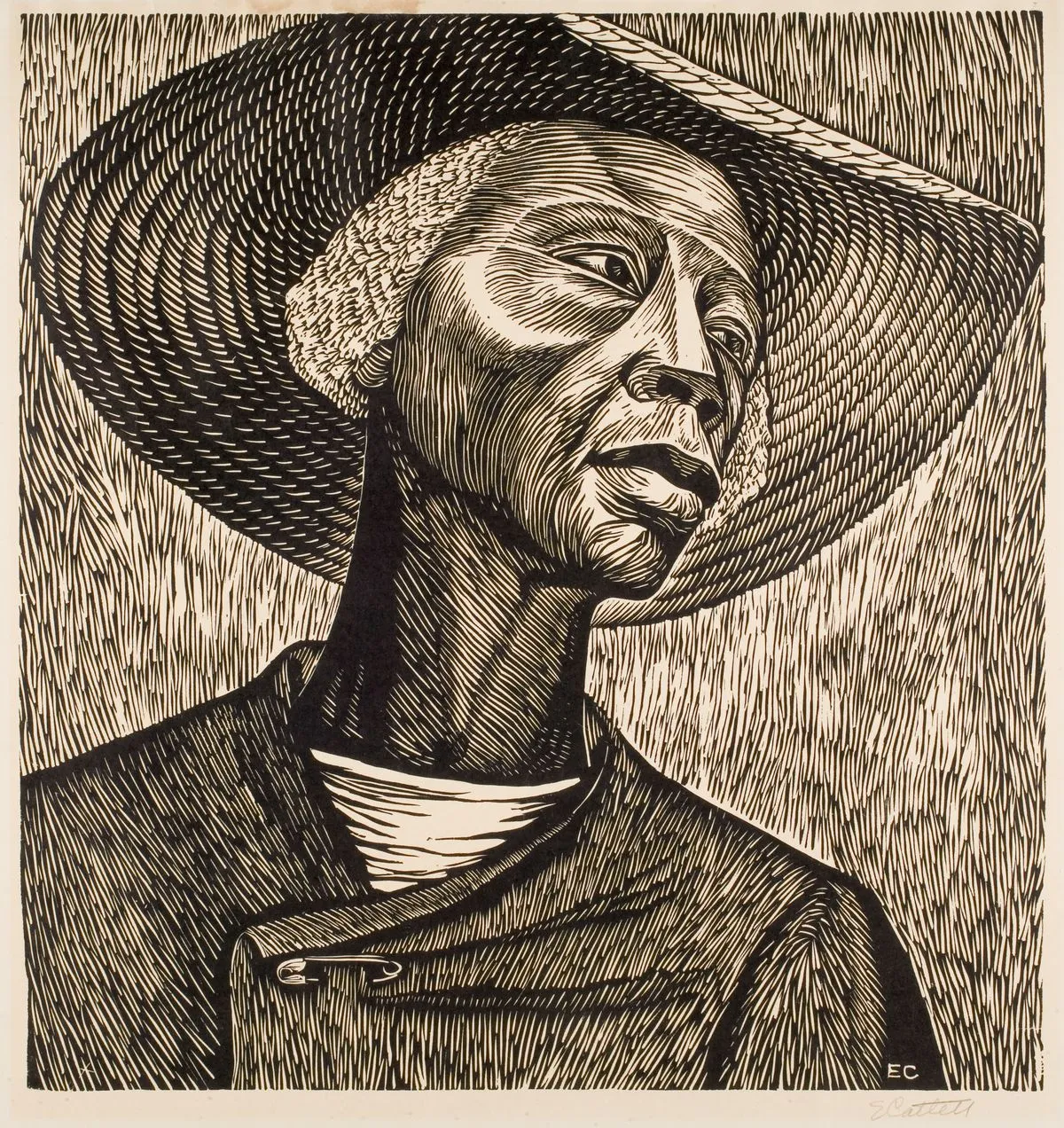

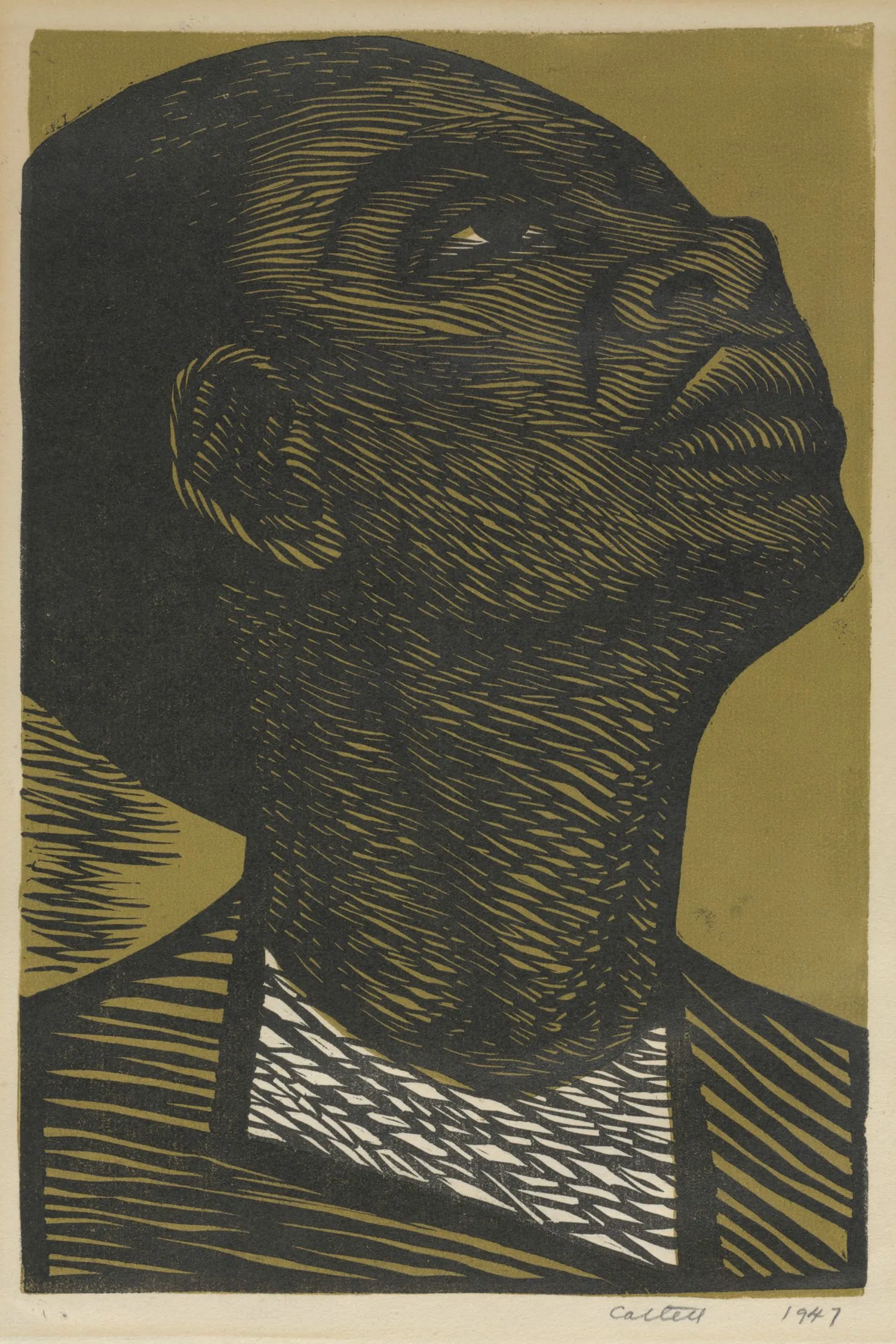

Elizabeth Catlett, I Am the Negro Woman, 1947. Linocut on paper. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Art by Women Collection, Gift of Linda Lee Alter, 2011.1.172. © 2024 Mora-Catlett Family / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

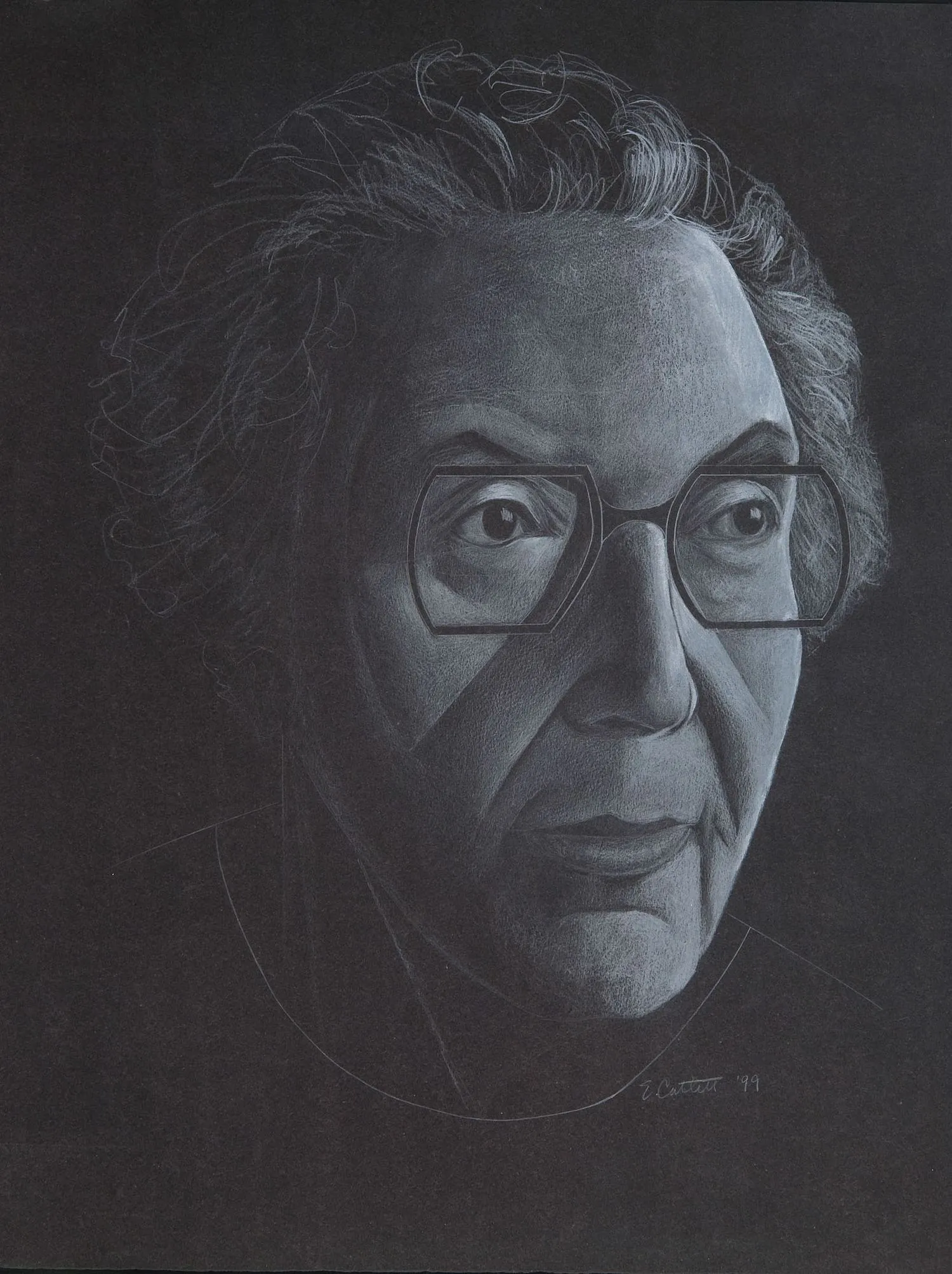

Elizabeth Catlett, I Am the Negro Woman, 1947. Linocut on paper. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Art by Women Collection, Gift of Linda Lee Alter, 2011.1.172. © 2024 Mora-Catlett Family / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY While America of the 1930s and 1940s was a hot mess of racial violence and economic and political tragedies and disasters, young Black artist Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) prepared to show the world how art can help address and hopefully change these conditions. Catlett's artistic interests were informed by her early experiences, but also the injustices, racial oppression, and social and economic marginalization of Black communities that continued in the following decades.

Often overlooked in art history herself, Elizabeth Catlett has received increasing recognition in recent years for her art and activist practice, incited in part by the present powerlessness of the left to offer a viable alternative to the growing right-wing politics that is taking sway around the globe. In search of alternative politics and powerful visuals that could help stamp this negative trend, Catlett emerges as a powerful source of inspiration and guidance.

The current exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, the first retrospective of the artist in an institutional setting, celebrates Catlett's legacy with a display of around 200 pieces, including drawings, sculptures, prints, and paintings. Titled Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies, it is an impressive overview of an artist who tirelessly pursued justice and used her formal language to reveal, educate, and incite change.

"Elizabeth Catlett's artistry and activism resonate powerfully in today's world, reminding us of ongoing national and international struggles against inequality and injustice. The exhibition not only celebrates Catlett's contributions to the art world but also brings a historical voice into the present—showing how generations of Black feminists continue to inspire us to fight for a more equitable and just society," said Catherine Morris, senior curator at the Brooklyn Museum.

The politically engaged art of Elizabeth Catlett combines different influences and art historical tropes, from abstraction and Mexican modernism to African and American visual traditions. Skilled artist, feminist, and activist, Catlett was guided by the principles of social justice and the belief that art should be accessible to all and conducive to social change. After she moved to Mexico, she embraced a political stance against imperialism, poverty, and racism that combined the goals of Black people, the feminist movement, and the Mexican Revolution.

"I am inspired by Black people and Mexican people, my two peoples," she declared in an interview with Ebony magazine in 1970.

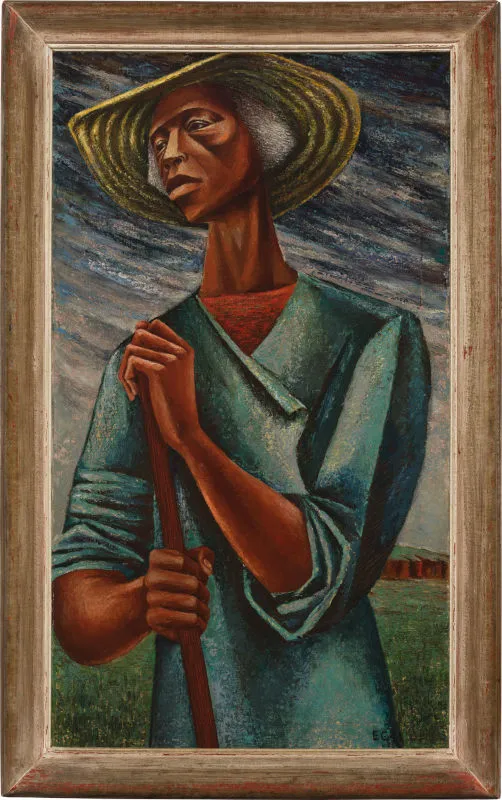

Catlett began her activist and artistic career in Washington, DC, where she was born in 1915. While in high school, she organized protests against lynchings but soon moved to the field of visual arts, through which she powerfully expressed her political interests. While studying at Howard University and the University of Iowa—where she became the first recipient of a Master in Fine Arts degree—she started making sculptures and was advised by the painter Grant Wood to create art about what she knew, which, in Catlett's case, included working-class Black people.

Her education continued at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she studied ceramics, and the South Side Community Art Center, where she perfected lithography. The four years she spent in New York City were dedicated to explorations of European modernist sculpture and engagement with Popular Front politics. She also created paintings and sketches that defy her characterization as exclusively a sculptor and printmaker. Combining formal rigor with progressive social politics on class, gender, and race became central to her practice and continued to dominate her activist and artist endeavors throughout her career.

Her steadfast commitment to anti-capitalist, anti-racist, and feminist ideals did not go unnoticed during the era of McCarthyism. After a brief period she spent in Mexico on a grant in 1946, she decided to relocate there permanently in 1947. She became involved with local leftist groups, artists, and transnational solidarity networks, and continued creating art at the revolutionary printmaking studio Taller de Gráfica Popular.

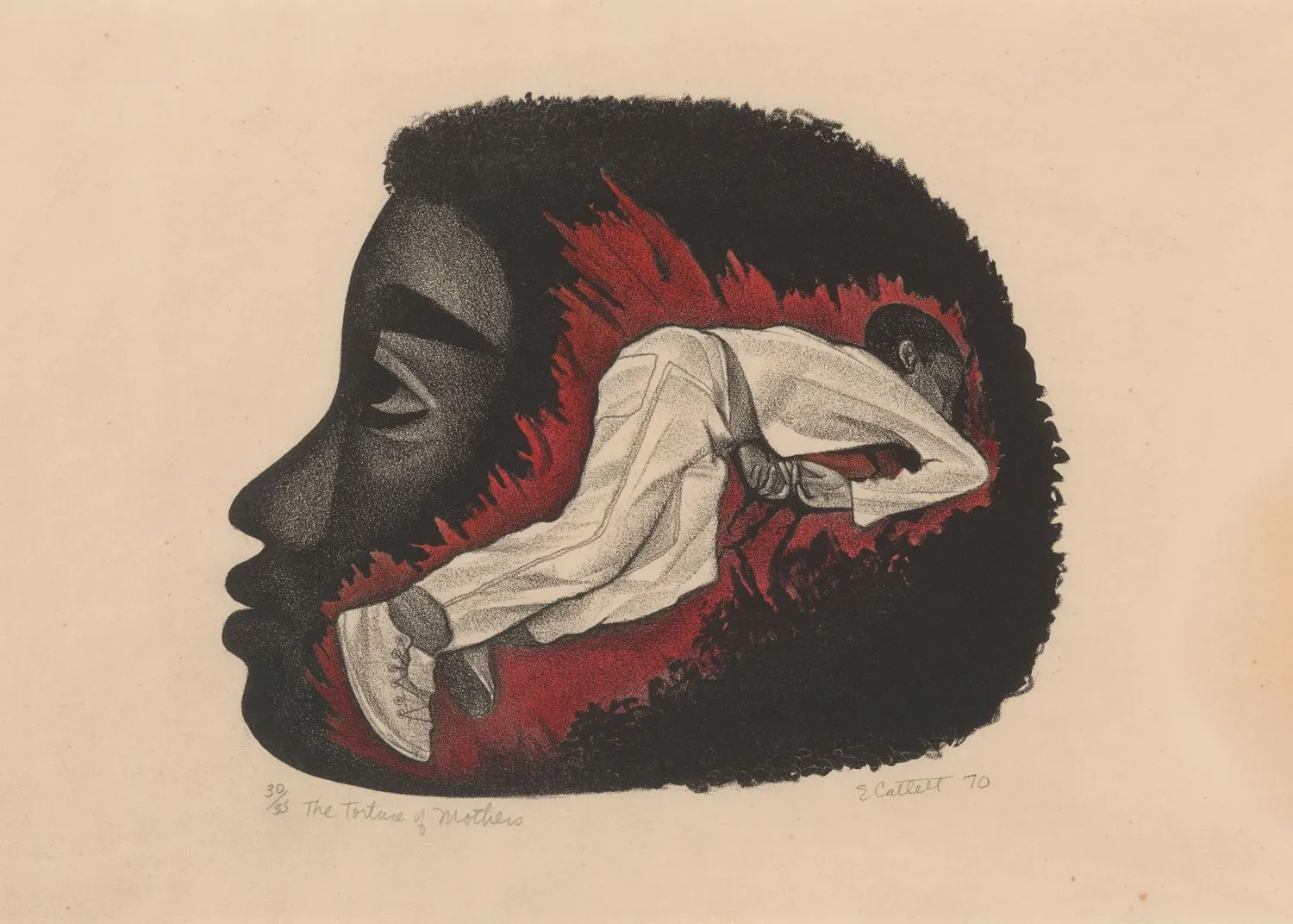

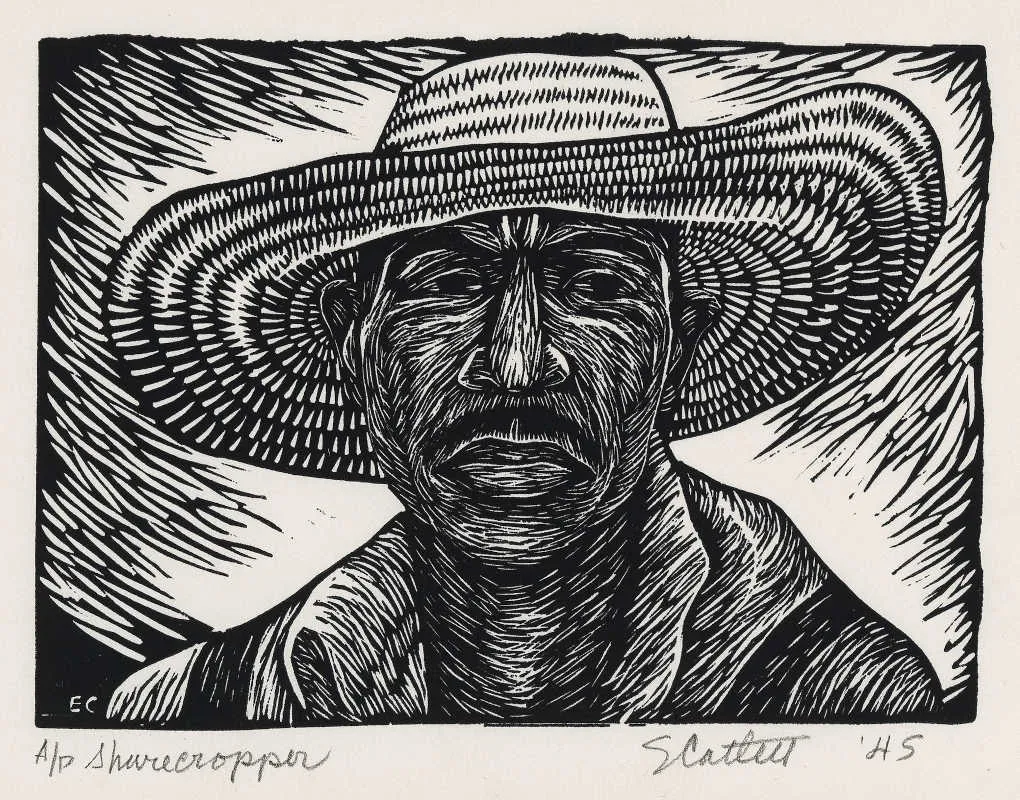

Her work from this period draws parallels between African American sharecroppers and Mexican campesinos—both communities enduring marginalization and othering rooted in colonial histories and practices. Getting acquainted with Mexican feminist circles, Catlett also embraced third-world feminism and continued to center Black women's experience in her practice. "Negro women in America have long suffered the double handicap of race and sex," she explained in a grant letter in 1945. Her 1968 sculpture Homage to My Young Black Sisters, created in her Cuernavaca studio, reflects her attitudes. A female figure done in cedar proudly raises her Black Power fist to the sky while her midsection is hollowed out.

In 1962, Catlett became a Mexican citizen but was simultaneously stripped of her American citizenship. Branded as an "undesirable alien" by the US government, she was banned from US soil for over a decade, and her citizenship was only reinstalled in 2002. This ban prevented her from attending a conference on Black Art at Northwestern University, but resolute in overcoming structural injustices and obstacles, she addressed the attendees via telephone.

"To a degree and in the proportion that the United States constitute a threat to Black people... I have been, and am currently, and always hope to be a Black Revolutionary Artist, and all that it implies!"

Although not able to visit the US, she remained engaged in the Civil Rights movement, and expressed solidarity through her engaging work, including linocuts celebrating Malcolm X and Angela Davis, among other Black revolutionaries.

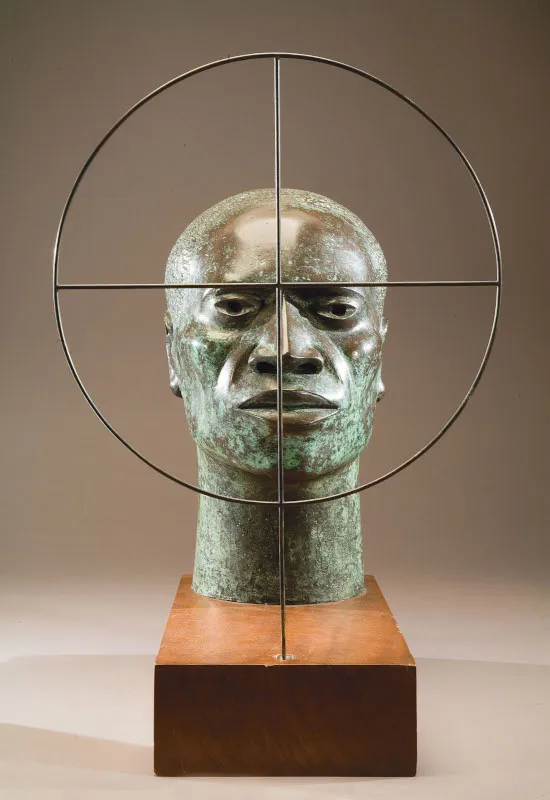

As a Back revolutionary artist, Catlett’s career represents a blueprint for leftist art activists who stand against oppression and marginalization, but also against the art institution, which still remains predominantly Western-centric and white. Despite facing challenges, including being a mother of three boys banned from her home country, Catlett did not relent when it came to her art. Indeed, her most powerful and poignant works were created while she faced hardship and ostracism. These include works in which she borrows from popular iconography, such as Target Practice (1970), made after the killing of two Black Panther activists in Chicago, featuring a bust of a Black man defiantly facing the viewers through a rifle's crosshairs, and Black Unity, from two years prior, one of her best-known sculptures shaped into the recognizable Black Power clutched fist from one side while the other features two faces done in the manner of African masks.

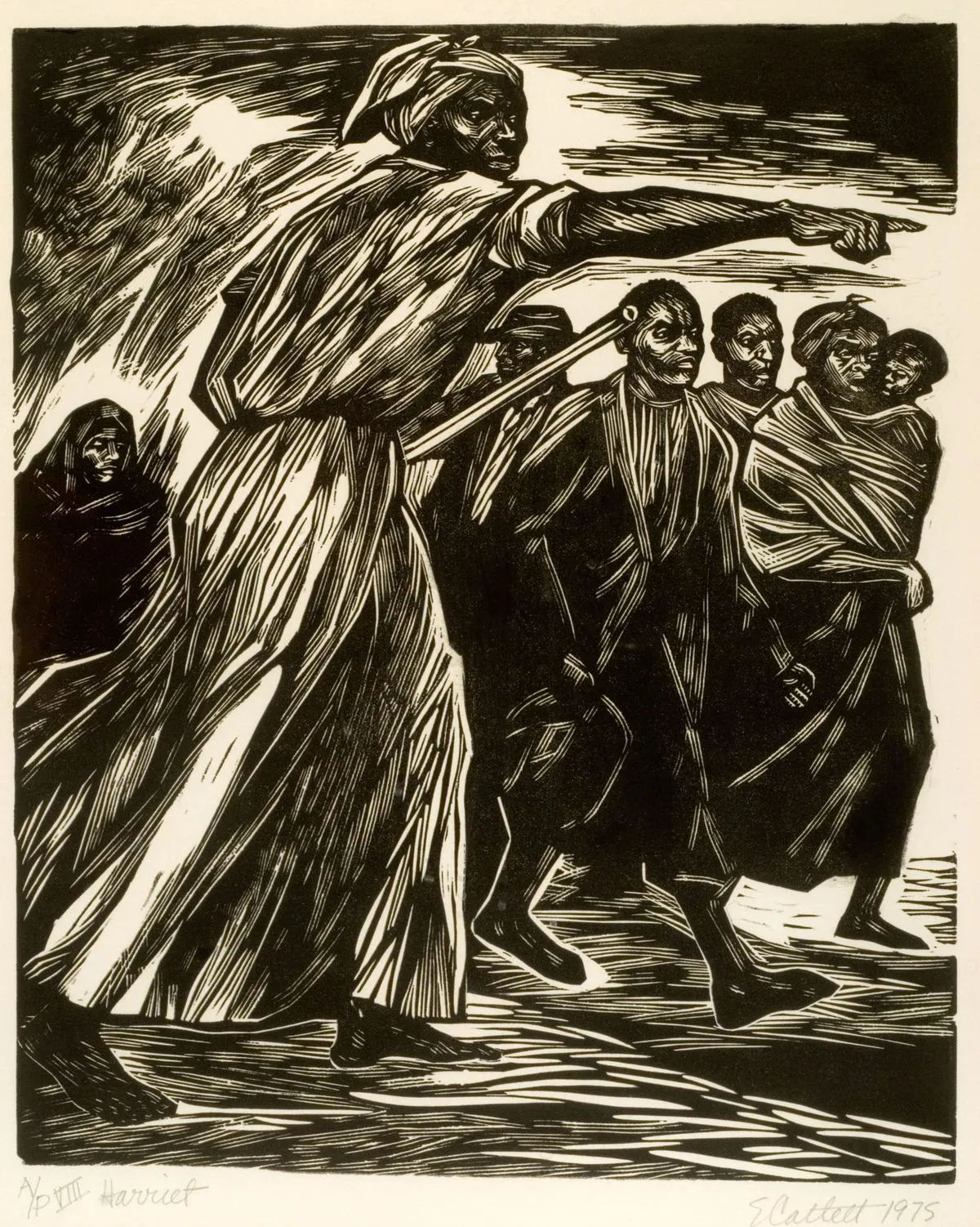

These, and many other works showcasing Catlett's craftsmanship and political commitment, are at the core of Brooklyn Museum's survey, organized chronologically and thematically, and charting her artistic development, themes that preoccupied her, and her activist engagement. In a series of linocut prints inspired by Mexican muralists and revolutionary graphics, The Black Woman, 15 images of African American women (including historical and fictional figures) are accompanied by a 15-line poem. A platform at the show features 14 sculptures of varying scales reminiscent of African and Modernist traditions done in a range of materials, from mahogany to bronze. She also reflected on her experience as a mother in the terracotta Mother and Child.

Besides being an artist, Catlett was also a radical educator who transferred her progressive politics from sculptures and prints to her classroom at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Her 'fugitive pedagogy', as art historian J.V. Decemvirale explains, meant that her Mexican students were not just taught technical craft, as in Western academia, but were made aware of the political histories and decolonial context in which they worked.

"In honoring Elizabeth Catlett's legacy, we hope that her work will resonate as a poignant reminder of art's power to ignite change and unite communities in the ongoing struggle for equality and liberation," concludes Dalila Scruggs, curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Organized in collaboration with the National Gallery of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago, the exhibition Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies is on view at the Brooklyn Museum until January 19th, 2025.