Master Plan for Reconstruction of Skopje City Center by Kenzo Tange

Master Plan for Reconstruction of Skopje City Center by Kenzo Tange Brutalism stands as one of the most intriguing and divisive architectural movements of the 20th century. Timidly emerging in the 1940s and flourishing in the decades following World War II, it arose from the necessity to rebuild cities devastated by conflict. This style was defined by its raw materiality and striking forms, with exposed concrete as its signature element. Brutalism wasn't just an aesthetic choice; it was a practical solution for a world in need of functional, cost-efficient, and durable structures.

What set brutalist architecture apart was its unapologetic embrace of honesty in design. Buildings showcased their construction materials and structural elements without pretense, celebrating utility while creating monumental spaces that commanded attention. Whether housing government institutions, cultural hubs, or residential blocks, brutalist architecture sought to be both practical and profound, often reflecting a utopian vision of collective living and civic pride.

Though met with controversy, the style gained a global following as architects explored its potential to reshape urban environments. From the sculptural forms of monumental public buildings to the rhythmic geometries of housing complexes, brutalism offered a platform for experimentation and individual expression. We take a closer look at the brutalist architects who defined the movement, examining how their designs not only shaped cities but also redefined the possibilities of concrete as a medium for bold, transformative architecture.

The list of famous brutalist architects must start with the father of modern architecture and the one whose influence mapped the trajectory of the 20th-century history of architecture and urban planning – Le Corbusier. Swiss-French luminary Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (1887 – 1965), widely known as Le Corbusier, is one of the most illustrious figures in the history of architecture, establishing himself as an architect, designer, Cubist painter, urban planner, and writer. Renouncing the decorative arts at an early stage paved the way for the pivotal Villa Savoye in Poissy, which exemplified the theoretical principles expressed in the Five Points of Architecture, a critical essay published in 1923 that determined the path of modern architecture, followed by numerous architects around the world.

Le Corbusier’s Unité d'habitation, an exceptional example of brutalism, presented a novel residential typology developed around those principles, which was built in several European cities and provided a worldwide model for a collective housing building. The most extensive urbanistic project executed in the brutalist vernacular surfaced in Chandigarh, India, and comprises a comprehensive urban plan for the new capital. Additionally, Le Corbusier personally designed the most significant buildings built within the city, such as the Palace of Assembly and the High Court of Justice.

Kentucky-born Paul Rudolph (1918 – 1997) is one of the most significant American architects who made his mark in residential and institutional buildings. Rudolph attained his education at Auburn University and the Harvard Graduate School of Design and attended Bauhaus for three years. In the early 1950s, Rudolph was based in Sarasota, Florida, expressing his modernist approach in numerous educational facilities and housing projects. This significant beginning defined him as an early proponent of the regional style marked as the Sarasota School of Architecture. Rudolph became a brutalist architect in the second half of the decade, shortly before being elected chair of Yale University's Department of Architecture. The Rudolph Hall, formerly the Yale Art and Architecture Building, completed in 1963, announced a new era in Rudolph's oeuvre, leading to his concrete masterpiece, the Milam Residence, designed and opened in 1961, and a prime example of sculptural brutalism.

After shortly studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, Marcel Breuer (1902 – 1981) enrolled at the Weimar Bauhaus under the mentorship of legendary Walter Gropius. The interdisciplinary approach of Bauhaus enabled Breuer to rise to prominence both as a brutalist architect and a furniture designer. At the behest of Gropius, Breuer moved to the city of London in 1937 before relocating to the U.S. to follow his mentor at Harvard's Graduate School of Design. Breuer's Wassily Chair and the Cesca Chair redefined the possibilities in furniture design, and his noteworthy buildings, such as the IBM Laboratory in La Gaude and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, verified the quality of Brutalism to merge monumentality and functionality. Brauer's unmissable building for the Armstrong Rubber Company, built in 1969, represents an outstanding example of brutalist qualities evoked in the building’s adaptability to a change of use. After it was known as the Pirelli Tire Building, it housed IKEA for a time before transforming into a hotel named Hotel Marcel as a tribute to its creator.

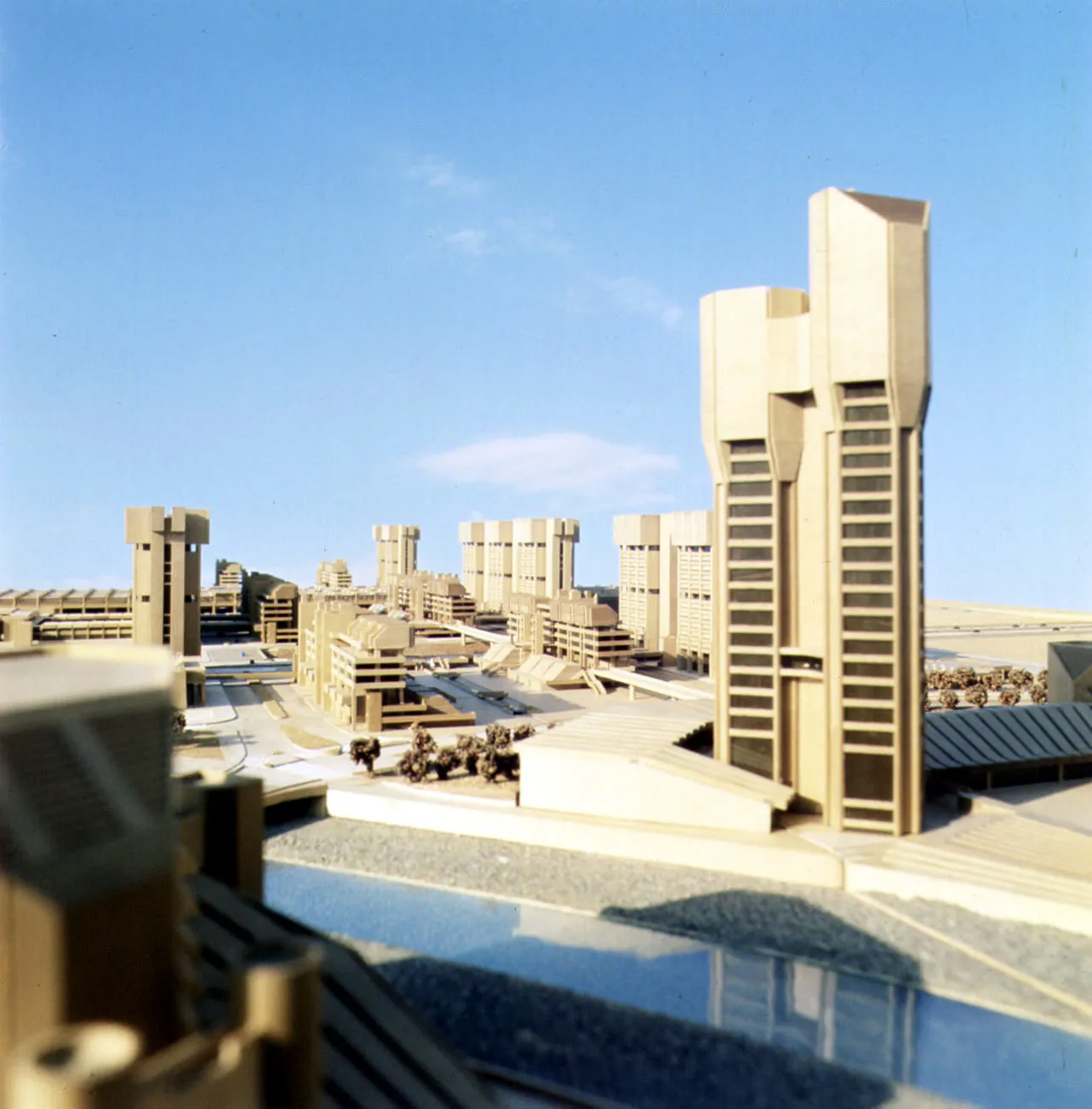

Japanese architect Kenzō Tange, although influenced by Le Corbusier at a young age, demonstrates a delicate mastery of bringing together traditional Japanese design with brutalist principles. Pritzker-Prize-winning Tange's artistry ensured projects across the world and a teaching position at the University of Tokyo. Tange's most notable project is the Peace Center in Hiroshima, initiated in 1950 to commemorate the devastating event of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945. Concrete columns support the magnificent horizontal structure of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which thus appears as if it is floating, manifesting the remarkable unity of Japanese heritage and brutalism. Tange also designed the Cenotaph in the Peace Center, which, along with his other projects such as the Ise Shrine and the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, reveals the majestic confluence of tradition and modernism inherent in his practice.

The brutalists architect of Hungarian origin, Ernő Goldfinger moved to London in the 1930s after graduating from the prestigious École nationale supérieure des beaux arts in Paris. Strongly influenced by Le Corbusier, Goldfinger transferred the principles of the Modernist architectural movement to his numerous educational and residential projects in the UK. However, Goldfinger is the most memorable with his housing structures, strongly imbued with a brutalist doctrine. The Balfron Tower, the nearby Carradale House in Poplar, and the later Trellick Tower in Kensal Town stand tall as monuments to Goldfinger's mastery, which ensure him an important place in the history of brutalism.

London-born Denys Lasdun (1914 – 2001) was instrumental in shaping England’s urbanistic landscape with a modernistic vernacular. A member of the Royal Academy of Arts, Lasdun can be easily considered the leading brutalist architect of the United Kingdom. Lasdun's early projects, such as Keeling House, introduced his aesthetics, defined heavily by designing a building in cluster blocks. The elegance of Lasdun's structures is evident in his masterpiece, The Royal College of Physicians, while the University of East Anglia exemplifies his precise use of modularity. Still, Lasdun's notorious building of The Royal National Theatre in London remains a powerful homage to the power of concrete and the limitlessness of geometry, earning him a significant spot in the history of brutalism.

Spanish architect Ricardo Bofill (1939 – 2022), the founder of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura, established in 1963, utilized technological innovation to create eclectic and authentic architectural aesthetics. Bofill's tumultuous beginnings were smirched by politics and marked by several arrests leading to his expulsion from the University of Barcelona. Forced to depart from Spain, Bofill moved to Geneva, Switzerland, in 1958, where he continued his education. Upon his return, Bofill founded the Architecture Workshop, intended as a multidisciplinary force rooted in Catalan traditions. Bofill became prominent with his grandiose housing projects, which he designed as amalgams of modern geometric forms and native Spanish architecture. Among them are Xanadu and La Muralla Roja in Calp and Walden 7 near Barcelona, Bofill's gem attributed to critical regionalism. Throughout his 50-year-long career, Bofill changed styles, continuously expanding and building the eclectic vernacular inspired by traveling, extending the definition of the brutalist framework.

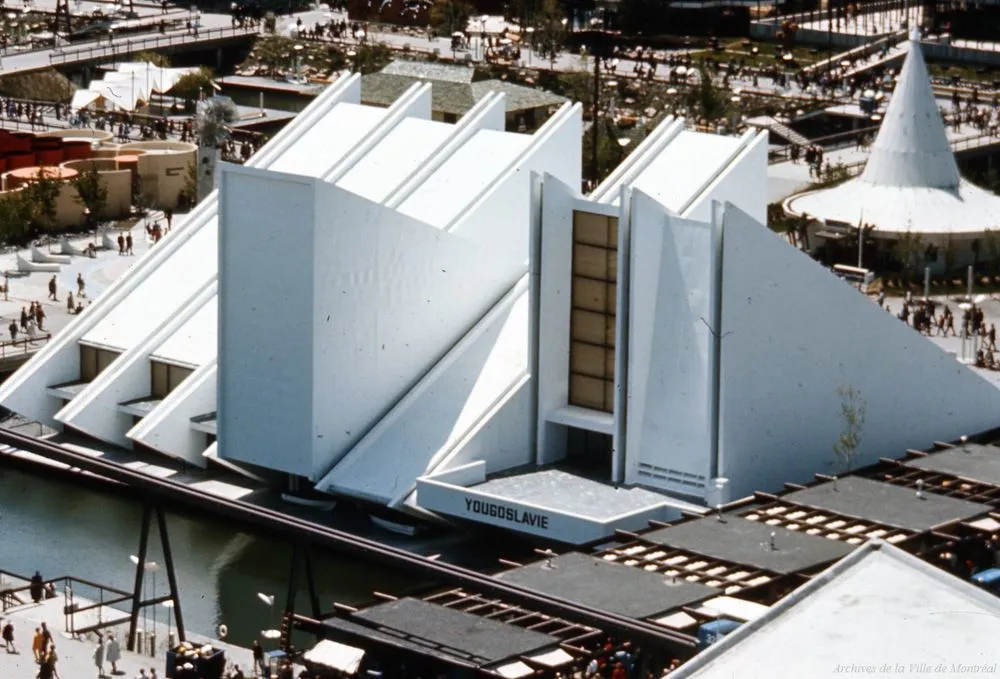

After graduating from the Department of Architecture of the Technical Faculty of the University of Zagreb, Croatian architect Vjenceslav Richter (1917 – 2002) formed the Exat 51 group as one of the founding members. Richter was the mastermind behind several museum projects and three Yugoslavian exhibition pavilions – in Brussels, Turin, and Milan. Among his notable buildings are the Saponija soap Factory in Osijek and Villa Zorje, a residential building built for the Yugoslav president Josip Broz Tito. Fascinated by systems and not afraid of experimentation, Richter rubbed shoulders with the New Tendencies movement, which sparked a series of works, such as Systemic Sculptures and Systemic Prints, intending to synthesize architecture and visual arts. Working at the intersection of art, Vjenceslav Richter excelled equally in architecture, painting, and sculpture. Although few of his buildings are kept in existence or realized, Richter has forever entered the pages of brutalism.