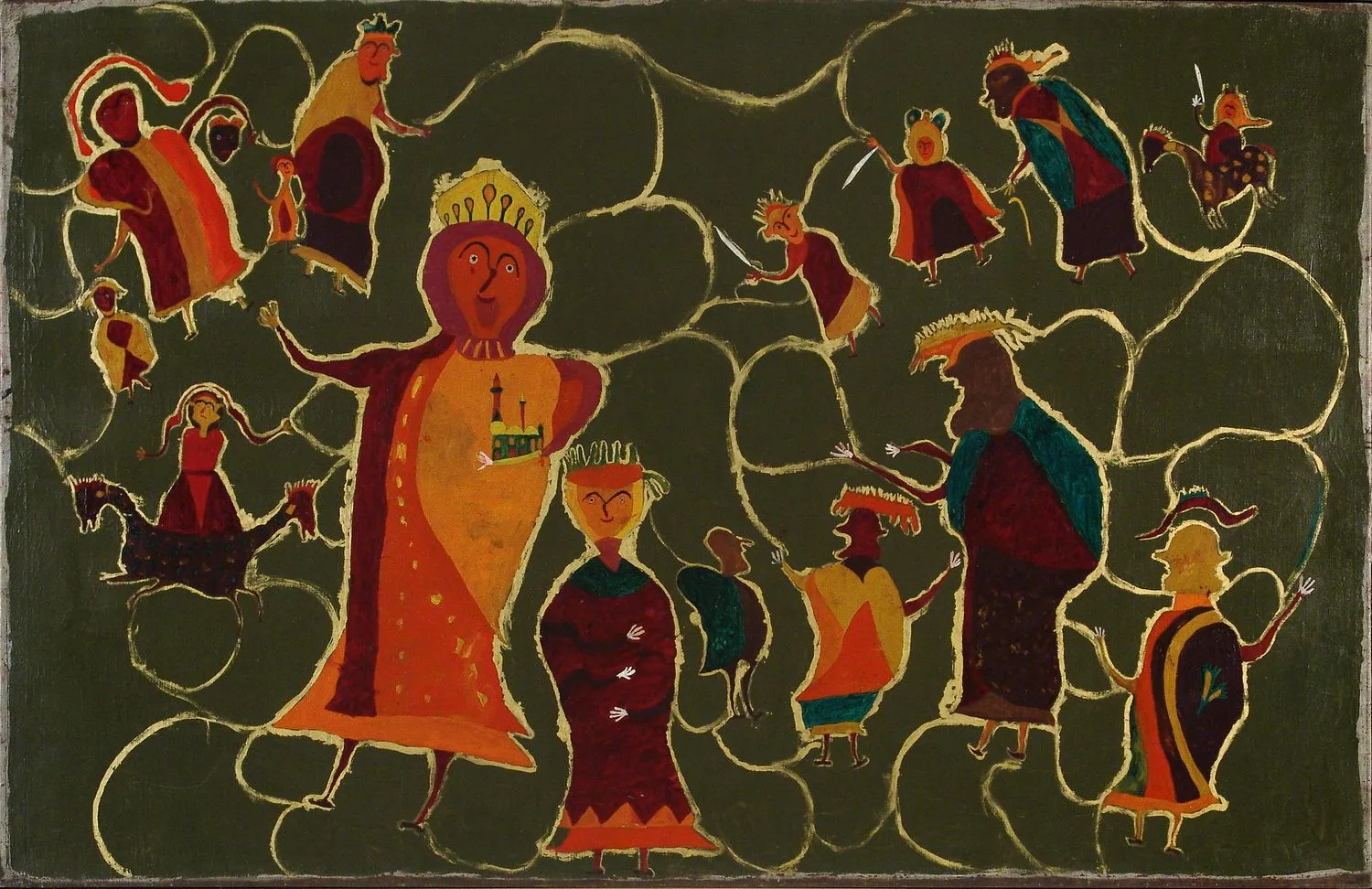

Ilija Bosilj, The Flight to Egypt, 1960. Oil on canvas, 57 x 70 cm. Private collection

Ilija Bosilj, The Flight to Egypt, 1960. Oil on canvas, 57 x 70 cm. Private collection During a recent guided tour of Ilija Bosilj's retrospective at the SASA Gallery in Belgrade, I had the opportunity to engage with a group of elementary school children. As we walked through the exhibition, I asked a simple question:

-What do you think, how old was Ilija Bosilj when he started painting?

The children quickly responded, voices overlapping with excitement:

-He was seven! Two! He was fifty! I think eleven!

-Why did most of you say he was that young?

-Because I can paint like that too! Because it looks like a kid painted it! It just looks like that!

-And why did you say he was fifty?

-(pondering) Because it looks good...

-Do you think all adults can draw well?

-(raised voices in unison) Noooo! My dad can’t even draw a stick figure!

-But why do you think some people draw really well? What are they called?

-(together, proudly) Because they go to school for that! They are artists!

-Okay, I’m going to surprise you, he was sixty-two when he started painting and he made more than two thousand paintings! And he did not go to art school, he was self-taught!

Entirely self-taught, Ilija Bosilj visualized his inner world through the bold use of colors, flattened perspective and delicate brush strokes, developing an unorthodox visual language that challenged the conventional ideas of what art "should" look like. However, behind vivid and seemingly childlike scenes—populated by fantastic creatures that blur the boundaries between reality and the physical world—lies a complex layer of personal mythology and symbolism. Unburdened by artistic expectations, children seemed to instinctively respond to the bold, unconventional style of his work with curiosity and wonder.

Titled Ilija Bosilj: Triumph of Art, a current retrospective at the SASA Gallery immerses us in the vibrant world of this self-taught artist. Curated by Ivana Bašičević Antić — Bosilj's granddaughter and Managing Director of the Ilija & Mangelos Foundation — the show brings together around a hundred works from museums and private collections, tracing his artistic journey through different chronological phases. The works reveal his fascination for mythology, religion and history, alongside a deep interest in symbolism. The exhibition also revisits the controversial Bosilj Affair, when his authorship was publicly questioned. Featuring texts from leading Serbian art critics and scholars, the exhibition highlights the ongoing conversation around Bosilj's unique legacy and places his work alongside that of his contemporaries.

Ilija Bosilj's art comes from a place outside academic rules or artistic schools, guided instead by a singular inner logic. Without formal training, he developed a visual language that's both symbolic and metaphysical, intuitive but carefully composed. His paintings move away from realistic space, favoring allegorical scenes that mix Orthodox iconography with invented cosmologies. Rather than illustrating the world, Bosilj constructed it anew—layering history, myth, and spiritual ideas into a visual order that escapes easy categorization. This unique approach forms the backbone of a practice that resists binaries like naïve or modern, outsider or insider, sacred or profane.

"It's hard to know life, but painting is easy. You just have to start on your own, then it flows by itself. One thing stacks on top of another, and when you finish the painting, you see that everything on it is colorful like in life, and that every truth has two faces." — Ilija Bašičević Bosilj

While Ilija Bosilj never received formal academic training, his personal circumstances led him to develop a distinctive visual language. Born Ilija Bašičević (1895-1972), he lived most of his life in Šid, a small town that was part of Austro-Hungary at his birth and is now located in modern-day Serbia. After finishing four years of elementary school, he took the traditional route of working on his family farm. The rural town of Šid offered few opportunities to engage with artistic trends of the time. Instead, Bosilj's early exposure to art came primarily from icons of the town's Orthodox church and the retelling of national epics at local gatherings. Nonetheless, he deeply admired the choice of career path made by his childhood friend and neighbour, Yugoslav modernist painter Sava Šumanović.

During World War II, when Šid was annexed by the fascist regime of the newly formed Independent State of Croatia, many prominent Serbs —including Bosilj and Šumanović — were marked for extermination due to their ethnicity. Bosilj managed to escape to Vienna with his two sons, but Šumanović was arrested and executed in 1942, along with many other Serbs from the region.

Although Ilija insisted that his children receive formal academic education — one of whom became the well-known Yugoslav art historian and conceptual artist Mangelos — he himself never pursued formal art training and took interest in painting quite late. During his time in Vienna, one of the cultural capitals of the era, Bosilj took advantage of the city's artistic offerings, discovering European art history through museum collections and engaging with the contemporary art scene, particularly the work of Gustav Klimt. These encounters shaped his newly found admiration for art. After the war, he returned to his hometown, now part of a radically transformed Yugoslavia, both socially and economically. Bosilj made his first painting at the age of sixty-two and continued until he died in 1972.

In 1957, Ilija created his first artwork, inspired by the icon of St. Cosmas and Damian, the patron saints celebrated during his family's slava—a Serbian Orthodox tradition honoring a family's chosen protector. However, he replaced the usual iconography of two saints shown together with a more direct approach that emphasizes their inseparable presence—portraying their two heads on a single body. This motif became a hallmark of his artistic language, giving rise to his famous two-faced humanoid figures.

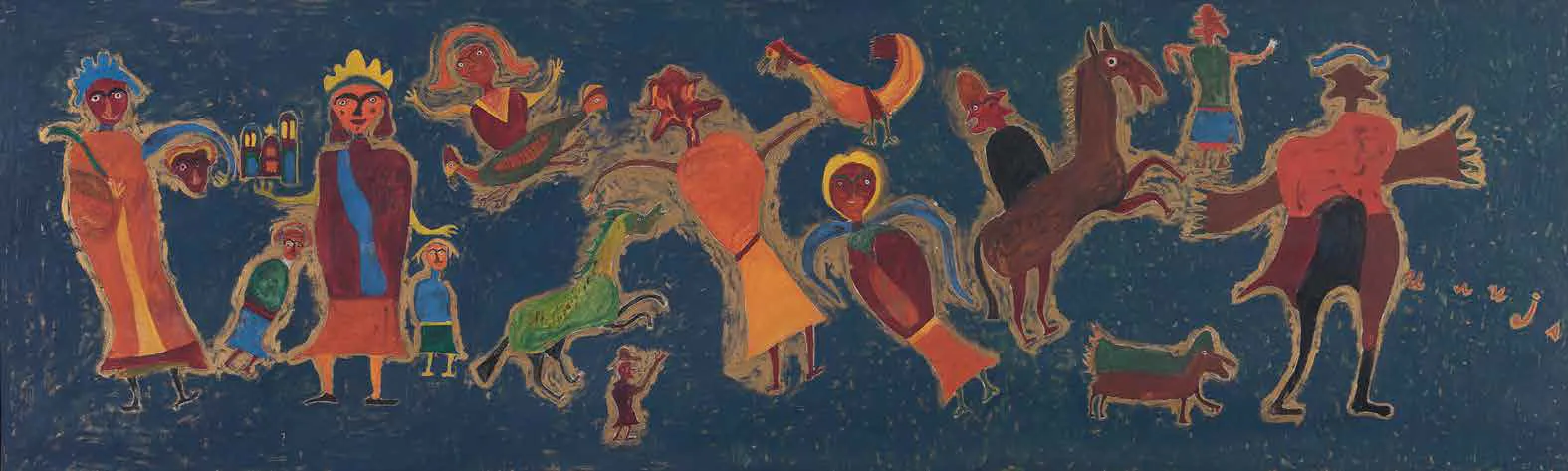

These figures, along with a variety of animals, appear throughout numerous cycles featured in this exhibition. They reimagine episodes from national epics, and recast historical heroes into mythical figures. Alongside these, stories from the Bible and visions of the Apocalypse offered him another rich source of imagery and meaning. As art historian Vojislav J. Đurić pointed out, Bosilj's compositions often drew on Byzantine and Baroque painting traditions—especially those found on the iconostases in the Srem region. But rather than copying these forms, he reshaped them into deeply personal visions that reflect his own unique way of seeing:

Ilija actually did step out of old iconographical models, but not until the unrecognizability of scenes and figures. The wild imagination added new layers of meaning to the old ones, reshaped the participants' appearances, added new emotional content to faces and movements, and created extremely unique works.

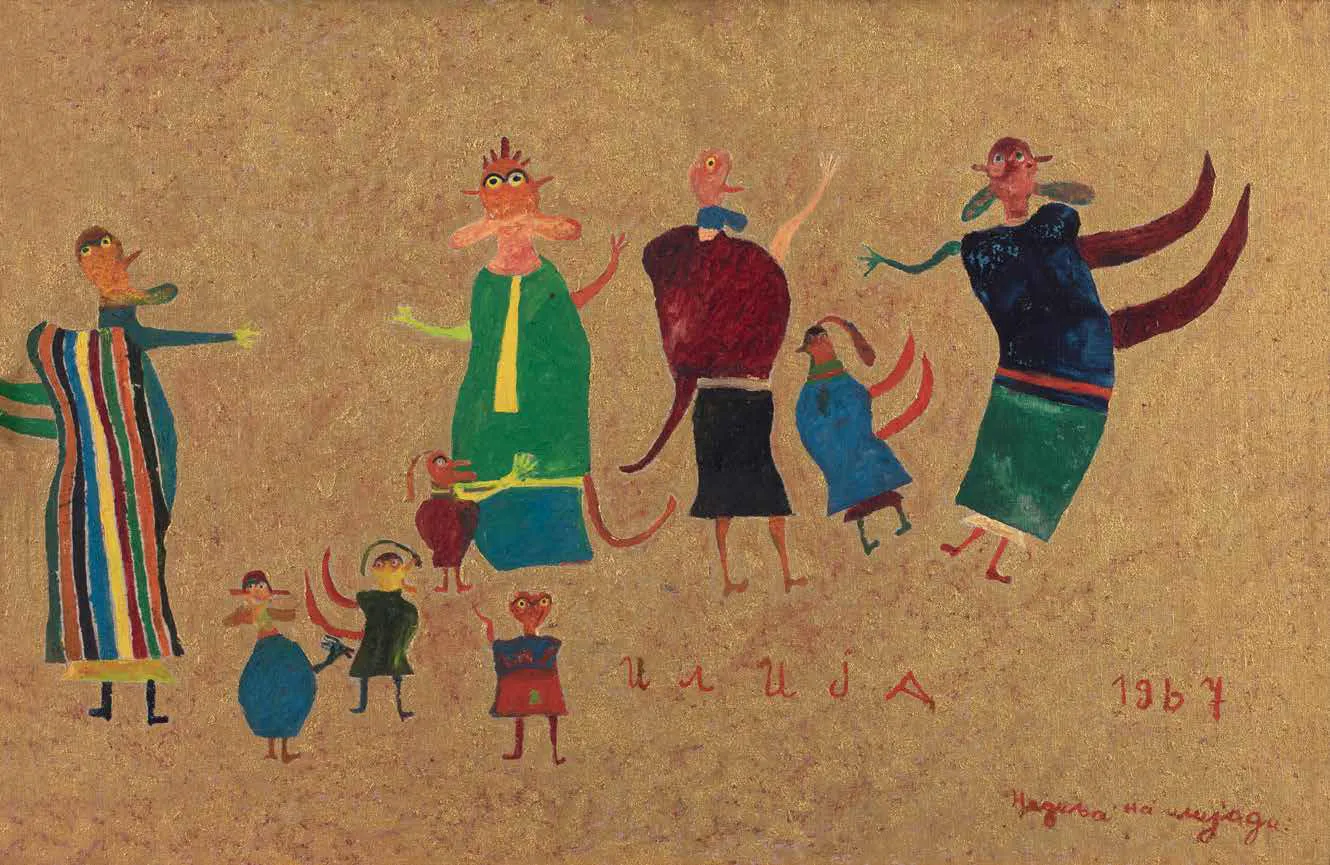

A step beyond interpreting myths is the creation of a personal mythological universe. Among his cycles, Ilijada or bits of my imagination, stands out as a deeply intimate body of work and a vivid and surreal realm inhabited by two-faced creatures and hybrid bird-like animals, set against vibrant backgrounds. Many of these works are adorned with gold contours and backgrounds, echoing the divine radiance and symbolism found in Orthodox icons while translating that symbolism into his own vision. The mythic dimension of this world rests on a personal symbolic code rather than inherited narratives, evoking an ideal world — a stark contrast to the one Bosilj had lived through.

His two-faced figures often embody the duality of human nature, suspended between virtue and malice. These hybrid beings also draw from life: according to his son, many were inspired by Bosilj's neighbors in Šid, but transformed through his imagination into strange, symbolic figures. Some are mocked, others lovingly immortalized in a fictional world shaped by his vision. They don't just represent archetypes and moral struggles—they also reveal the personal and often ironic way Bosilj saw the world around him.

A different kind of duality is reflected in the name of the cycle itself: Ilijada is derived from the artist's own name, Ilija, but it is also the Serbian word for Homer's Iliad. Through this witty and self-referential title, Bosilj cleverly connects his personal universe to the grand epic tradition, while completely redefining it—inviting viewers into a space where old structures break down and the lines between memory, myth, and invention start to blur.

"Everything, then, with Bosilj was directed towards the sky, towards spiritual ascents that constantly drove him across some vastness known to him only. I had the impression that I was faced with the ancient codes of a vanished world, that I had entered a secret chamber in which the magic words and signs of a world were stored, the world that was just gaining its first experiences in facing the eternal truths of life and death."— Dejan Medakovic, art historian

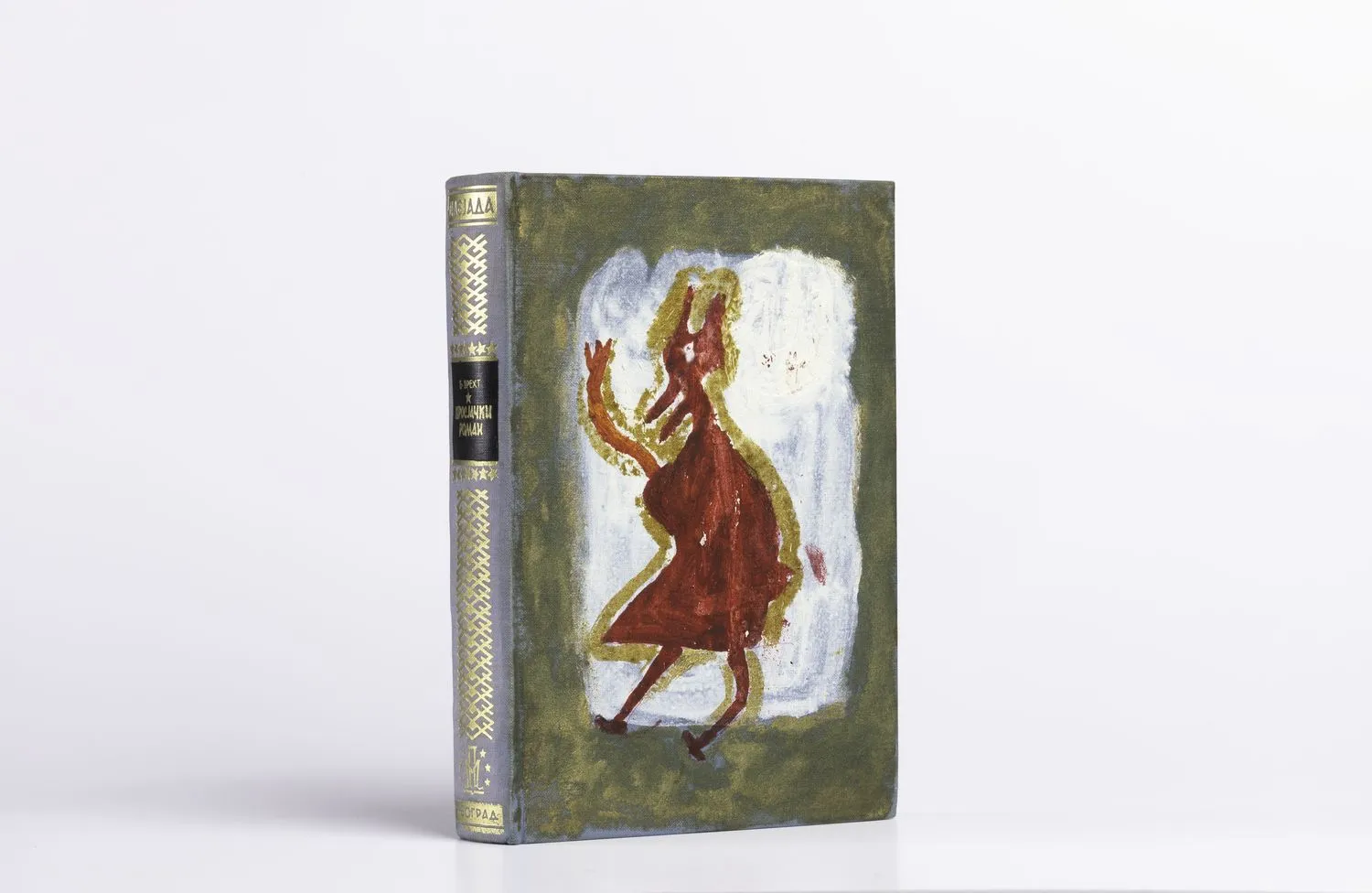

Bosilj's inventiveness extended beyond traditional canvases, reflected in his distinctive approach to surfaces and materials, and his transformation of everyday objects through artistic intervention. In the 1970s, he repurposed books from his personal library, treating their covers as painting canvases. His signature figures appear on these covers, prompting intriguing questions about their relationship to the diverse contents—ranging from classical and Yugoslav literature to history and art theory. While the precise reason Bosilj chose book covers remains open to interpretation, his inclusion of these transformed books alongside traditional paintings in his catalogue highlights the breadth and experimental nature of his practice, with possible associations to the concept of the artist's book.

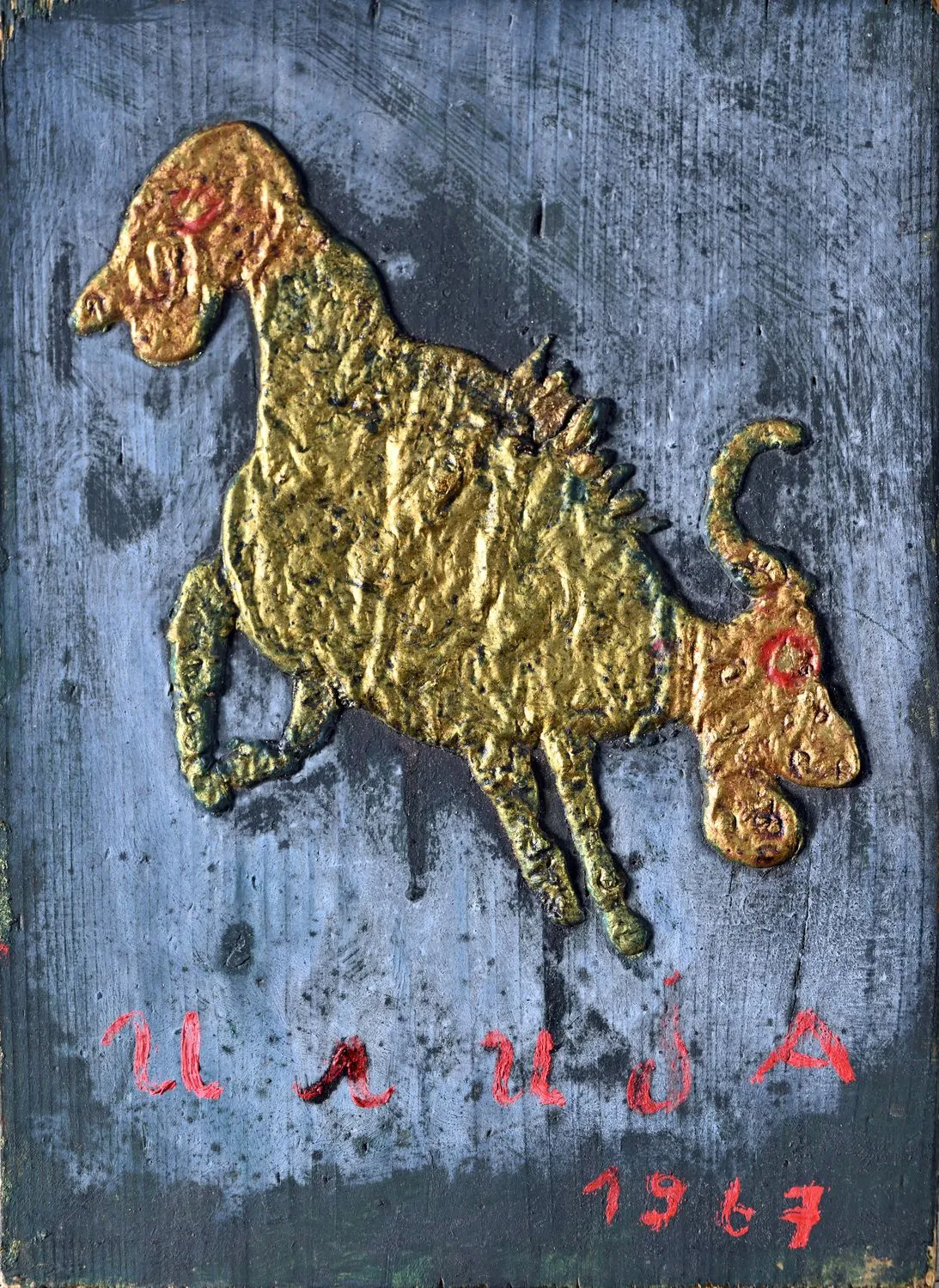

Both the painted books and his later "thick gold" technique marked significant shifts in his approach to materials and form. The latter involved covering wooden blocks with a dense mixture of oil and bronze powder, resulting in irregular, relief-like shapes. Abandoning careful brushwork, Bosilj allowed the substance to drip, mix and harden freely, introducing a more expressive, tactile dimension to his practice. These works verge on visual abstraction, preserving meaning through form and image titles, rather than figurative representation.

While uniquely Bosilj, these works gesture toward some of the concerns explored by Yugoslav informel and conceptual artists of the time. The exhibition emphasizes these connections by placing Bosilj’s work in dialogue with that of leading Croatian informel artist Ivo Gatin and Serbian conceptual artist Raša Todosijević. When shown side by side, Gatin's and Bosilj's "thick gold" works reveal striking formal affinities, both exploring the materiality of paint while loosening ties to representational content. In contrast, works by Todosijević inspired by Bosilj's universe honor his determined defense of authorship and quest for recognition, while also critiquing the institutional structures he struggled against. Two large tapestries made after Bosilj's designs by Atelje 61, a workshop specializing in tapestry production, further reflect the ongoing interest in his work across artistic disciplines.

Bosilj's work was included in exhibitions both in Yugoslavia and abroad, eventually finding its place in major collections such as Jean Dubuffet's Collection de l'Art Brut and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. However, international acclaim did not shield Bosilj from polemics and scrutiny in his home country. The controversies culminated in 1965, in the so-called Bosilj Affair, when the artist was forced to prove his authorship by painting in front of an expert commission in Zagreb.

The accusation came from Krsto Hegedušić, a prominent Croatian painter and influential figure in the institutional art scene, whose doubts cast a shadow over Bosilj's artistic credibility. Critics were unsettled by his unconventional use of materials, suspecting that his work was too closely aligned with contemporary and avant-garde practices to have emerged from an untrained hand. This affair was further amplified by media speculation, as journalists sought to unmask the identity of this self-taught artist and question the artistic "purity" of his voice.

At its heart, the ordeal revealed the gatekeeping tendencies of the art world and its unease over who gets to define artistic legitimacy. After completing several works under observation, the commission formally confirmed Bosilj's authorship. Yet the experience reinforced a bitter truth: the world of artistic freedom he so deeply valued was still governed by the same hierarchies he had long resisted.

Revisiting the earlier discussions with kids, it becomes clear that Bosilj's work consistently challenges assumptions about what art—and who an artist—can be. While many trained artists sought to shed their formal education in pursuit of raw, instinctive expression, Bosilj took the opposite path—developing a visual language rooted in personal vision, emotional truth, and limitless imagination. His commitment to style an honest, singular worldview triumphed over conventional norms that often confined the art scene.

Today, his paintings continue to speak powerfully to audiences across backgrounds and generations, forging immediate, emotional connections. The work of this self-taught artist, once challenged by the academic circle, is now honored in the Gallery of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, accompanied by texts from notable members of the Academy who engaged with his work.

The exhibition Ilija Bosilj: Triumph of Art will be on view at the SASA Gallery of Visual Arts and Music in Belgrade until June 8th, 2025. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalog written by Ivana Bašičević Antić, also featuring essays by scholars Vojislav J. Đurić, Dejan Medaković and Ješa Denegri.