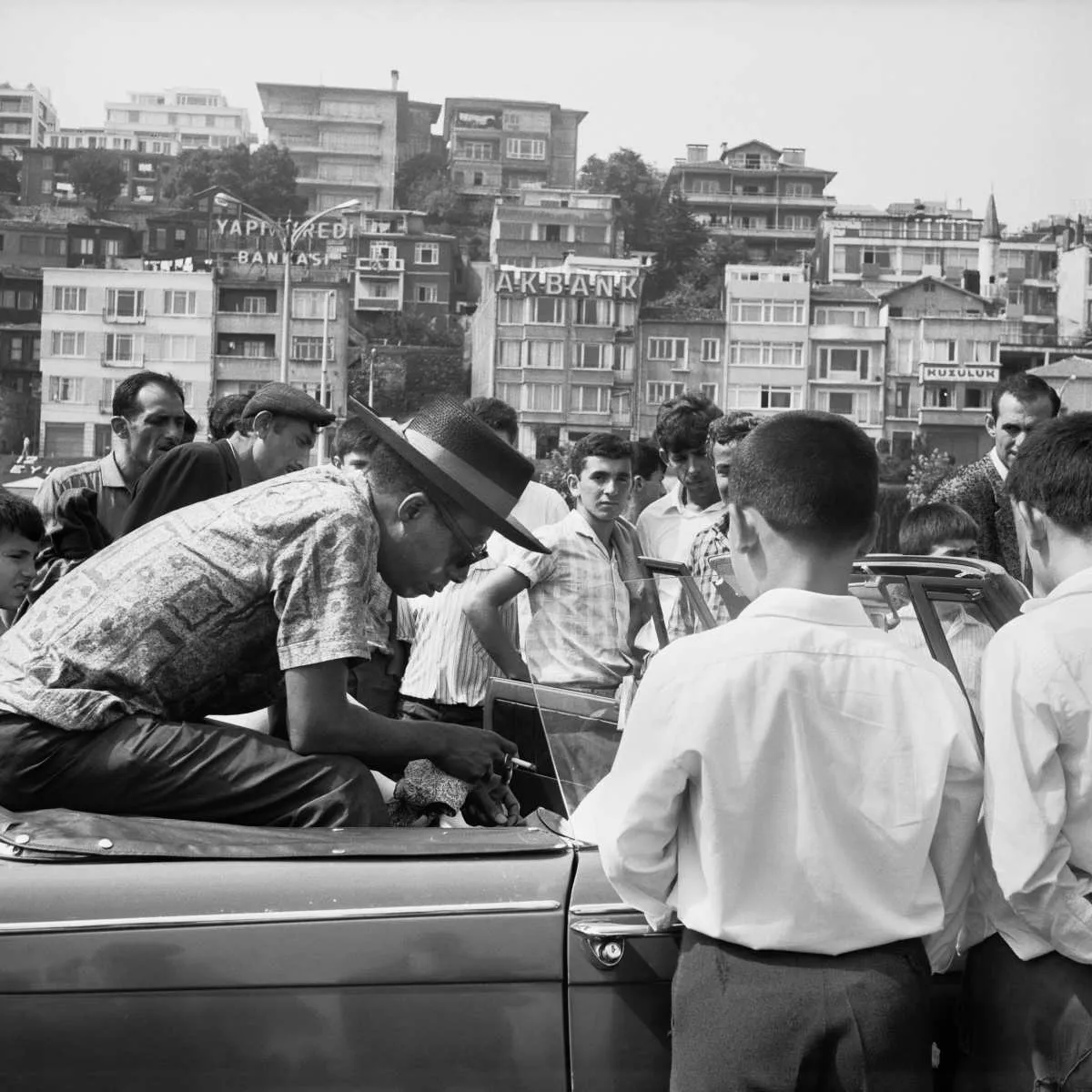

Sherbet seller, customers, and Baldwin at Yeni Cami (New Mosque), Istanbul, 1964 or 1965 © Sedat Pakay

Sherbet seller, customers, and Baldwin at Yeni Cami (New Mosque), Istanbul, 1964 or 1965 © Sedat Pakay "I cannot imagine a more beautiful country or kinder people than the Turks," celebrated American writer and activist James Baldwin (1924-1987) once said in an interview, a statement that found its way into the FBI's extensive 1,884-page file on him.

Seeking refuge from the racism and homophobia of mid-century America—and grappling with the personal trauma of losing a close friend to suicide—Baldwin set out on a journey that would profoundly reshape his worldview. In Turkey, he found solace after years of depression marked by the assassinations of Civil Rights Movement leaders. There, by the Bosphorus, he regained his writing rhythm, formed new friendships, and produced some of his most celebrated work.

After an extended stay in Paris, the first stop on his European tour, James Baldwin arrived in Istanbul disillusioned, virtually penniless, and on the brink of losing his mind, as his Turkish friend Engin Cezzar later described. From that moment on, everything changed for the better.

Baldwin's transformative years in Istanbul were captured in a series of photos by Turkish photographer Sedat Pakay, offering a rare glimpse into the writer's life. They are currently on view at the Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) as part of the exhibition Turkey Saved My Life – Baldwin in Istanbul, 1961–1971, which explores Baldwin's transformative years in the city, his observations on Turkish society, his circle of friends, and the moments that inspired his writing.

"Turkey Saved My Life provides insight into how Baldwin shaped both his writing and his unflinching commitment to civil rights," said Linda E. Johnson, BPL President and CEO. "James Baldwin's work continues to resonate as powerfully today as it did during his lifetime," she explains, "and we are honored to celebrate his legacy and vision of justice."

James Baldwin lived in Istanbul from 1961 to 1971. At the time, the megalopolis was beaming with small private manufacturers, and was also a building mecca, bringing in many skilled and unskilled workers. The city was growing and was seen as the leader in Turkey's national development, attracting many visitors. Although the country became a secular republic following Atatürk's reforms, it still preserved its Islamic identity, visible in Istanbul on every corner.

Baldwin's time in America had been defined by grief, struggle, and alienation. The loss of close friends, the pervasive climate of racism, and his deep personal battles left him weary and disillusioned. But arriving in Istanbul, he found a stark contrast—an unexpected sanctuary. This vibrant city, alive with cultural richness, offered Baldwin a sense of peace and freedom he had never experienced before. Istanbul, with its complex social fabric, provided the space to breathe, to heal, and, most importantly, to write.

Baldwin walked through Istanbul's winding streets, where the air was filled with the aroma of spices and street food, browsing sahaflar—second-hand bookshops—and exploring the city's bazaars. In the bazaars, the colorful displays and the buzz of activity created an ever-changing rhythm that Baldwin found both comforting and inspiring. He embraced the city's tea-drinking culture, often stopping for tea near the New Mosque, and watched the bustling fishing community set off into the waters of the Golden Horn. Friends introduced him to local taverns and hotels, with the Divan Hotel becoming one of his favorite haunts. He also spent time in the northern neighborhoods where Robert College was located.

Far from America, Turkey was a land of freedom for Baldwin. "I feel free in Istanbul," he told Yaşar Kemal, a Turkish writer and friend.

Although consumed by Istanbul's allures, he did not forget America, and the looming threat of its imperialist foreign policy was felt in Turkey as well. The Cold War was in full swing, and the world braced for the possibility of another conflict.

As the political landscape grew more complex, Istanbul became a stop for many American political and cultural figures—some of whom Baldwin hosted. Among them was Marlon Brando, who, in mid-1966, used Cezzar's car to explore the city while his limo served as a decoy for paparazzi. Baldwin also entertained U.S. State Department officer Kenton Keith and his wife, Brenda.

Although Baldwin left America battered and broke, with the manuscript of Another Country still far from finished after years of struggle, Istanbul quickly became a place of healing. His first stop was the home of Engin Cezzar, a Turkish actor he had met in New York and cast as Giovanni in his 1957 production of Giovanni's Room. Cezzar had long invited Baldwin to visit, and he finally arrived—years later and unannounced—at Cezzar's Taksim Square apartment, where a party was underway. After a brief introduction to the guests and a bath, Baldwin fell asleep in an actress's lap.

Istanbul and the close circle of friends Baldwin formed in the city—including Engin Cezzar, Gülriz Sururi, Cevat Çapan, Zeynep Oral, Sedat Pakay, Oktay Balamir, and Ali Poyrazoğlu—housed, nourished, and inspired him, offering both refuge and companionship as they helped him bring many of his writings to completion.

The unfinished book Another Country, which had left Baldwin depressed and suicidal, took only months to complete in Istanbul. After he settled at Cezzar's, the creative spark returned, and the book was completed in a few months. Baldwin's spirit changed as well. "Turkey saved my life!" he would later exclaim; it was a place of healing, a place where he could begin again.

Beyond Another Country, Baldwin wrote several significant works during his time in Istanbul, including Going to Meet the Man (1965), Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone (1968), No Name in the Street (1972), The Fire Next Time (1963), and Blues for Mister Charlie (1964).

He also engaged in the production of the play Fortune and Man's Eyes which explores the sexual lives of gay men in prison, a novelty on Istanbul's scene that rarely engaged with such topics.

Embarking on a journey from America to Europe in the late 1940s, Baldwin confessed to his friend, drama critic Zeynep Oral that the atmosphere in the country felt suffocating. "I can't breathe—I have to look from the outside," he told her. Beyond the racial inequalities and homophobia that defined U.S. society at the time, Baldwin was also seeking respite from the intense struggles of the Civil Rights Movement.

Although Istanbul provided Baldwin with a sense of renewal, certain moments reminded him of the harsh realities he left behind in America. One such moment occurred when he was subjected to racist and homophobic slurs, followed by an attack by two men while visiting a coastal village, as Baldwin scholar Magdalena J. Zaborowska discusses in her book James Baldwin's Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile. The social realities of Turkey, too, were not lost on Baldwin. He was acutely aware of the persecution of the Kurdish minority and, in a letter to a friend, he lamented that it seemed, at times, that "the entire world is no longer livable."

Although aware of Turkey's complex reality, Baldwin appreciated its freedom. Istanbul was both a place of exile and Baldwin's newfound home. As he reminisced, it was "easier to be gay in Istanbul than in America, easier to be black."

The Istanbul period remains the most successful in Baldwin's career and the one that profoundly reshaped his thinking about home, race, and identity. As he wrote in Giovanni's Room, home was not a place at all, but an irrevocable condition.

"The place in which I'll fit will not exist until I make it."

He abandoned the idea that home is a place where he would finally feel like he belonged; instead, he embraced the transitory idea of home as a feeling and a condition that one creates for oneself. This brought him profound peace.

Baldwin also observed a more relaxed and affectionate dynamic between men in Istanbul, where it was common for them to hold hands and kiss in public, regardless of sexual orientation. Furthermore, the concept of race seemed more fluid than what was prescribed by Western notions of racial categories, challenging Baldwin's understanding of racial divisions, and prompting him to adopt a more nuanced perspective on identity.

Baldwin's relationship with photographer Sedat Pakay played an important role in documenting this period. Their connection grew from shared intellectual interests and mutual respect, with Pakay capturing intimate, candid moments of Baldwin's daily life in Istanbul. Their relationship extended beyond photography; they engaged in discussions on race, identity, and the experience of being an outsider in different parts of the world.

Pakay's images provide a rare glimpse into Baldwin's evolving sense of belonging and personal transformation. They document his social interactions, cultural immersion, and moments of quiet reflection, showing him engaged with friends, enjoying Turkish tea, and strolling through Istanbul's lively streets. Other images capture Baldwin in more introspective moments, offering insight into his personal growth and the peace he found in this new environment. These photographs serve as a testament to a man in transition, forging a sense of home beyond borders.

In addition to his photography, Pakay directed the 1973 short documentary James Baldwin: From Another Place, which captures Baldwin's reflections on race, exile, and identity while living in Istanbul. The film, like his photographs, offers a deeply personal portrait of Baldwin during this formative period. In the film, Baldwin articulates the tension between escape and the inescapability of race:

I left America because I doubted my ability to survive the fury of the color problem there. I wanted to prevent myself from becoming merely a Negro; or even, merely a Negro writer.

Yet, as he acknowledges, leaving did not mean shedding the weight of his identity:

I've been forced to deal with the world in a certain way because I was a black man, because I was born where I was born. That has shaped my sensibility, my outlook, my vision.

These powerful reflections, captured in Pakay's film, underscore Baldwin's evolving understanding of home—not as a fixed place, but as a condition that is shaped by history, identity, and the act of survival.

Pakay's images and film provoke a deeper reflection on the conditions of exile, the complexities of belonging, and the enduring struggles against sexual and racial injustice that continue to shape our present moment.

In an era marked by displacement, political unrest, and the fight for recognition, Baldwin's journey reminds us that retreating from the familiar can be an act of survival, resistance, and renewal. By forging a sense of home beyond borders, he was at home, the home that was in him, and all around him.

The exhibition Turkey Saved My Life - Baldwin in Istanbul, 1961–1971 will be on view at Brooklyn Public Library until February 28th, 2025.