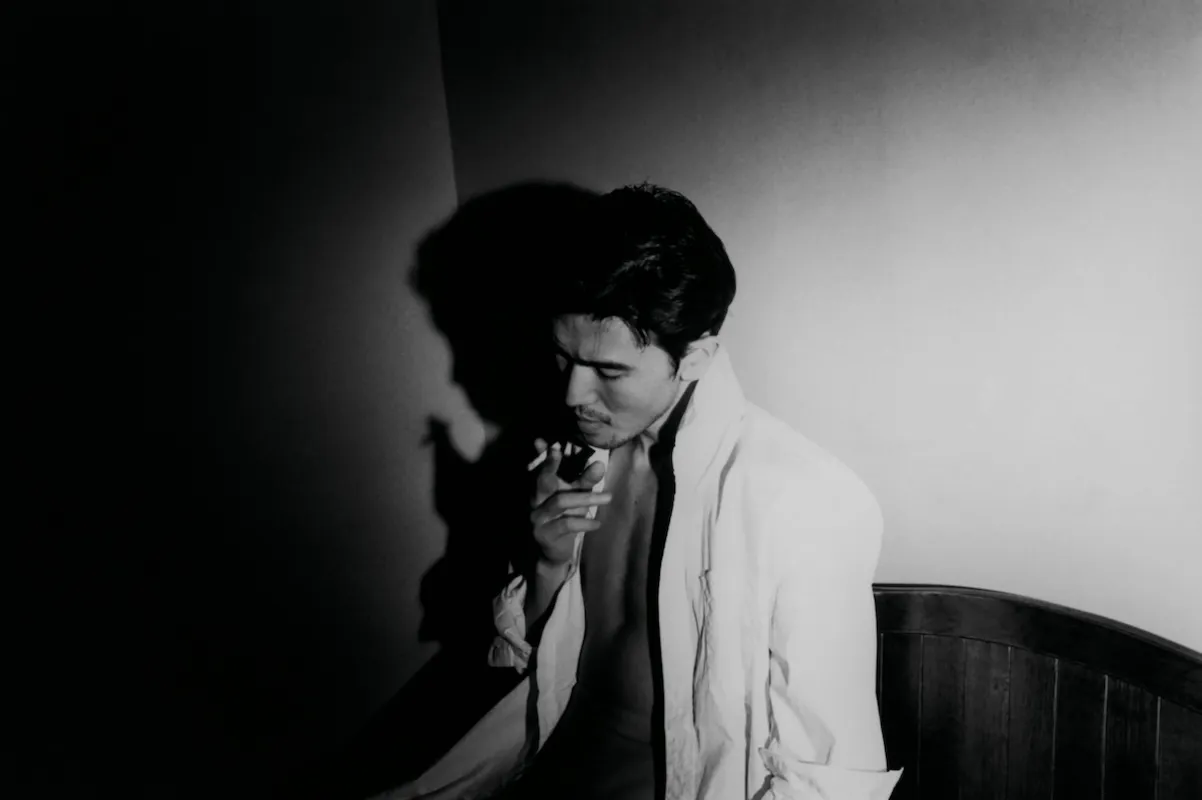

Narahashi Asako, Kawaguchiko, 2003; from the series half awake and half asleep in the water. Courtesy PGI gallery, Tokyo, and Aperture

Narahashi Asako, Kawaguchiko, 2003; from the series half awake and half asleep in the water. Courtesy PGI gallery, Tokyo, and Aperture For quite a long time, art history has been an intensely gendered field, narrated by and about men. In recent years, however, we have witnessed a surge of efforts that have been invaluable in rewriting the narrative toward a broader perspective disengaged from the patriarchal view. Among them is a collective endeavor spearheaded by Aperture to shine a new light on the history of Japanese photography, condensed in the just-released publication titled I'm So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now.

In Japan, the situation has been particularly challenging for women photographers due to the profoundly ingrained linguistic, social, and cultural stereotypes. In a still largely conservative society, women should be submissive, quiet, charming, gentle, and disempowered. In other words, they are constrained by the roles society imposed upon them–a daughter, a sister, a wife, and a mother. These attitudes about a desired femininity have perpetrated intense gender disparities that have sidelined women as agents in the medium until the late 1990s and early 2000s. For decades, women photographers were ignored or labeled inferior to their male counterparts, resulting in their work being obscured, non-credited, and rarely exhibited.

Edited by Pauline Vermare and Lesley A. Martin, with the curator and writer Takeuchi Mariko and photo-historians Carrie Cushman and Kelly Midori McCormick, I'm So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now offers a precious glimpse into the diverse practices of Japanese women photographers, touching upon the women pioneers in the medium. Twenty-five artist portfolios represent the heart of the publication.

Focused on practices from the second half of the 20th century and today, the book features the work of female artists from various generations, styles, and approaches. In an equal measure, it spotlights established and emerging women photographers, including those whose work has been out of the public eye despite its quality. Additionally, the book features a detailed and richly illustrated bibliography and several interviews and seminal texts on photography that have been translated for the first time. Anchored by three critical essays, the book meanders through the historical and contemporary corridors of a vital chapter in the history of photography that has long been obscured.

Despite the substantial gaps in archival material, Carrie Cushman and Kelly Midori McCormick illuminate the nearly-forgotten stories about women pioneers in the medium. The text unearths the fascinating stories of the first smiling photograph, created by Shima Ryū, who photographed her husband in 1864, and the first essay written in 1907 by a women photographer in Japan, Tokuriki Sakuko. After working in the shadows, both these women opened their studios after their husbands' deaths, gaining autonomy in the highly gendered world of late 19th and early 20th century Japan.

These isolated instances paved the path for Yamazawa Eiko, the first woman to open a photography studio in Osaka. In the 1920s, Yamazawa worked in San Francisco and New York, where she learned the secrets to operating in a studio and the inexhaustible possibilities of portraiture photography. Upon her return to Japan, Yamazawa opened her professional studio, counterpointing the stigma around women's labor. She experimented with portraiture, developing a new photographic technique, and mentored more than a dozen women in the craft that functioned as a mode of emancipation. Often portrayed in Japanese newspapers as a model for shokugyō fujin (white-collar professional woman), Yamazawa Eiko famously remarked in 1935:

There can be no liberation of women while they are hired by men and always work in worse conditions than men. A bright future is promised only when as many women as possible learn their own mission to live and discover their jobs.

Not much changed in the post-war era. Women still had to fight the notion of considering women's photographic work as temporary, marginal, and reserved for women before marriage. Those who dared opt for a professional dedication to photography struggled to break the barriers of a male-dominated domain. Of particular note is the 1976 all-woman exhibition Hyakka ryōran (One hundred flowers in bloom) organized by photographer Ishiuchi Miyako at Shimizu Gallery in Yokohama, as well as the 1989 show Japanese Women Photographers: From the 1950s to the 1980s at the Lehigh University Art Galleries (LUAG) in Pennsylvania.

The latter was organized by Ricardo Viera, who initially intended to stage a show dedicated to experimental Japanese photographers. Upon hearing that women artists were also part of the show, the male photographers threatened to withdraw, prompting Viera to change his curatorial concept entirely. The tides substantially began to shift in 1995, when Nobuyoshi Araki nominated Hiromix for the New Cosmos of Photography. The potent spotlight on her practice created the conditions for greater visibility of Japanese women photographers. Two years later, US-based Japanese curator Fuku Noriko curated the exhibition An Incomplete History: Women Photographers from Japan, 1864–1997 at the Visual Studies Workshop gallery in New York, extracting the immense legacy of Japanese women photographers from anonymity.

In their struggle for recognition, Japanese women behind the camera had to tackle many hurdles, including the perpetual objectification and commodification of women's bodies. Brimming with eroticism, photographs by male artists, starting with the already mentioned Araki, empowered the sexism toward the Japanese female body. However, the issue had its roots during the American occupation of Japan, and many female photographers focused on the complexities of women's bodies during the postwar years. Among the photographers who captured the nuances of red-light districts and bars near the American military bases of Yokohama and Okinawa were Tokiwa Toyoko, Ishiuchi Miyako, and Ishikawa Mao. These images bring poignant testimonies of women’s experiences by women, foregrounding the tensions beyond the sexually-charged narrative.

In a different series, titled 1•9•4•7 (1988–1989), Ishiuchi photographed the bodies of women born in 1947, just as the artist, and were turning forty at the time. She focused on particular body parts, such as hands and feet, capturing the transformations that tell a delicate story about the passage of time, aging, and change. Nagashima Yurie took the world by storm with her nude family portraits in the early 1990s. Recording her life from her student days through pregnancy and motherhood, Nagashima took on the roles of model and photographer simultaneously to address the dated norms imposed on depicting the Japanese female body.

The book also foregrounds the mesmerizing work of Okanoue Toshiko, who explored the intersection of tradition and modernity. Anchored in the traditional Japanese art of tearing, painting, and assembling pieces of paper or hari-e, Okanoue created extraordinary collages that adopted femininity as a strength, leaving a lasting mark within the global Surrealistic movement. It also discusses in-depth the strides made in contemporary photography, such as the establishment of onnanoko shashin or the "Girly Photo" genre, the diaristic nature of the shishashin or "I-photography," and the use of performance and installation, for example, as ways of to extend the dialogue across different media. Here, the work of contemporary artist Tokyo Rumando particularly comes to the fore. Fusing performance and photography, she dresses in a high-school uniform or applies geisha makeup to call out and address the typical stereotypes, often alluding to a manga aesthetic.

Titled after the adapted verse by Kawauchi Rinko, I'm So Happy You Are Here echoes Pauline Vermare's feelings of joy and admiration while preparing the book. Being an invaluable contribution to illuminating the identities, nuances, themes, and qualities of Japanese women photographers, this book will surely leave no reader indifferent. It blends and intertwines the narratives and practices of Japanese women photographers who adopted the medium as an instrument of empowerment and emancipation. It underlines the importance of women's perspectives in photography in addressing various societal issues, adding to the discussion of femininity, identity, ethnicity, motherhood, gender roles, and more.

Coinciding with the book release, an eponymous exhibition debuted at Rencontres d'Arles in France over the Summer. In January 2025, the landmark show will travel to the Fotomuseum Den Haag in the Netherlands, with more locations yet to be announced.