Jeffrey Gibson, 2023

Jeffrey Gibson, 2023 Jeffrey Gibson's practice is built on relationality and care, exploring how communities gather, how stories move, and how materials carry the weight of shared histories. His work spans more than two decades of paintings, sculptures, installations, and performances, drawing from Indigenous making traditions, queer aesthetics, pop music, and protest culture to imagine forms of belonging that refuse erasure.

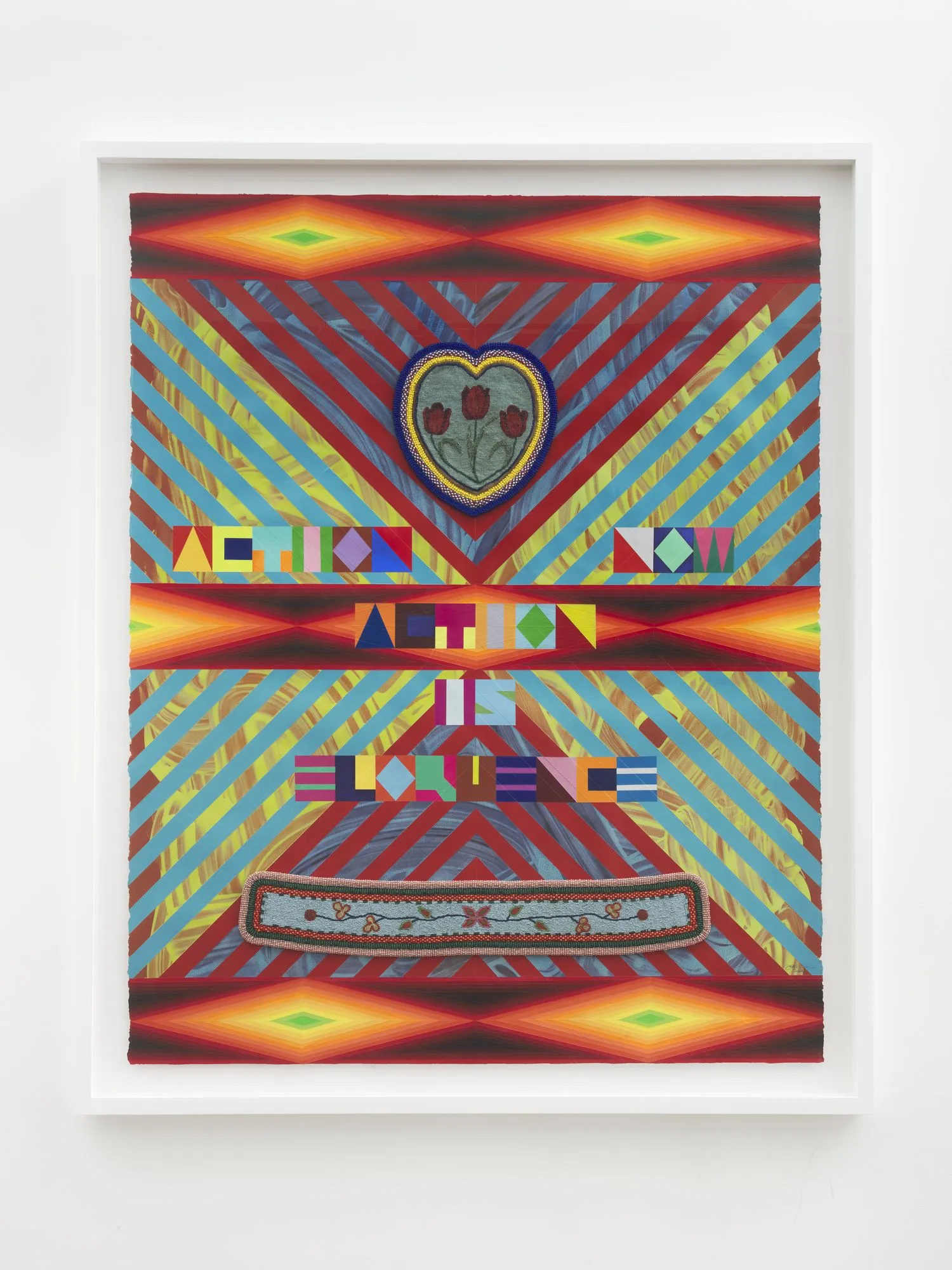

His work insists on multiplicity—of identities, histories, and communities—and uses saturated color, pattern, and movement as tools to challenge the narratives that have long shaped American cultural memory. Whether beading language from civil-rights speeches, remixing museum artifacts, or staging spaces for collective gathering, Gibson builds environments where complexity is welcomed rather than smoothed away.

This ethos expands powerfully in POWER FULL BECAUSE WE'RE DIFFERENT at MASS MoCA, a commissioned installation that fills the vast Building 5 gallery. Conceived as an open, celebratory space for Indigenous and queer performance, the project centers seven monumental garments suspended from teepee poles and activated through movement, sound, and community-led events.

The installation channels regalia, club culture, and two-spirit histories, while a mirrored wall, fused-glass stages, and video works create a kaleidoscopic environment in which difference becomes both structure and spirit. Over its eighteen-month duration, the exhibition invites Indigenous performers, thinkers, and makers to shape the space from within, turning the gallery into a living, collective site rather than a static display.

At The Broad, the space in which to place me extends Gibson's critically acclaimed U.S. Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale—marking the first time an Indigenous artist represented the United States with a solo presentation. Bringing together paintings, sculptures, flags, murals, and video, the exhibition centers resilience and resistance while interrogating the documents, languages, and images through which America has defined itself. Gibson's works transform citations of systemic injustice into radiant declarations of presence, carving out a space where belonging is not granted from above but built, shared, and continually affirmed.

In our conversation, we talk about making space, holding complexity, and imagining futures beyond the narratives that have shaped us. We explore the shifting politics of representation, the complexity and diversity of Native American identities, how making and performing garments creates agency and presence, and how the concept of Two Spirit opens new possibilities for recognition and belonging. He speaks about history as something lived rather than inherited, about making as a site of agency, how communities carry one another, the small, persistent acts that open new ways of being together, and the potential of art to imagine what might yet be possible. His reflections are rooted in relation—on making, listening, and moving through the world with integrity.

Jelena Martinovic: Your work engages with resilience, community, and cultural continuity. Over time, how has your approach to these ideas changed, especially as the cultural and political landscape around you has shifted?

Jeffrey Gibson: It's really strange. Part of it has to do with who I am as a person, my core self. I was raised outside of the United States for a large portion of my life, in Germany and Korea. Experiencing being American and Native American abroad—being a foreigner, living in other cultures, not knowing the language—shaped my empathy for all of those roles, between being in your homeland and being a foreigner.

I'm also a kid of the 1980s and 1990s, and at least in my experience, youth at that time had a sense of optimism about the future—that it would be intercultural and multicultural, this kind of coming together. That's what I gravitated to. My high school years were spent immersed in pop culture: rave scenes, house music, drum and bass, pop, and queer nightclubs. This was the late 1980s and early 1990s. I was aware of the AIDS crisis, but I wasn't immediately impacted by it. Later, as an adult, I realized that the older individuals around me were going through an intensely traumatic and political time.

I think I continue to craft a space and environment that gives others the same sense of connection and possibility that I experienced. Trauma—of all kinds—has a hugely disruptive impact on individual development and on the ability to imagine, receive love, care, and build community. I often think about Native American history in terms of the interruptions to cultural survival, community building and the integrity of community.

In the 1990s, I worked on the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act at The Field Museum. That was my first job working in a museum, and it was huge for me. It was all about cultural translation of what one audience sees, what another audience knows, and the different kinds of knowledge, and who holds that knowledge. It taught me that it's okay not to know everything. There's a kind of obnoxiousness in feeling that you need to know everything, in the fetishization of the "other" and what we don't know about the other. I learned to let people have their privacy. I don't need to know it all. It's okay not to understand everything.

Over the course of my life, I've often found myself in environments where things have become increasingly politicized on the surface level. It's not that they weren't political before, but the upper, more visible layers of things now feel more overtly politicized. It's made me look back on history—and when I say history, I mean really going back into U.S. history.

One thing I've realized is that I've largely let go of the search for whatever we might consider "authentic" or "traditional," because time stretches back further than we can even mark. Time goes back so far, and humans from different backgrounds have interacted for longer than we can even mark. When I look at historical objects, what fascinates me most is knowing that anything I'm seeing really comes from multiple cultural origins. For me, there's nothing beneficial in trying to pinpoint a specific origin. It's not that I don’t understand why we might want that, but I'm not sure it serves where we are today.

This thinking was central for me in Venice. I wanted to look at historical objects, aesthetics, and materials and acknowledge Native and Indigenous makers as creative minds who made choices. That gives the maker integrity and responsibility for their work. I connect to that as a maker myself.

Making is powerful. In the studio, we sew and work with textiles. It's empowering to know how to make clothing for yourself. We grow up thinking value comes from buying something in a store, seeing it in an ad, or watching someone else wear it. But making something for yourself—deciding why you put it on your body, what it says to others—is a radical act. It opens up questions about materials, labor, mass production, environmental impact.

Looking at historic objects, I often think about the stress Native communities were under when they made some of the most beautiful, laborious things. I find myself asking: why would you do this? It feels counterintuitive that, in times of duress, you would create something so intricate, intense, and beautiful. For me, personally, what I see in that work is a manifestation of hope. It's a micro-expression of the ability to make something under pressure, to keep making choices. The moment we begin to feel that we have no choices is dangerous. And I don't mean to suggest that people in difficult situations have an abundance of choice—but even the smallest awareness that you are making choices, in the minutiae of daily life, is powerful. It affirms that sense of agency.

All of this continues to guide me, especially at this point in my life, as I think about how I want to move forward. It always comes back to what is humane—how we, as humans, relate to one another. The darker side of humanity comes from pain and fear, and the impulse to inflict that on others. Through my work, I try to build the world I want to live in.

Jelena Martinović: Being the first Indigenous artist to represent the US at the Venice Biennale with a solo exhibition was a historic moment. What did that platform mean to you personally? And how do you feel it's influencing conversations about representation within major art institutions?

Jeffrey Gibson: It's an interesting moment because younger generations are no longer satisfied with just representation. At one point, representation was about wanting to see ourselves in places where we didn't see ourselves. But now, younger people are saying, "No, we don't want this. We're not fighting to be in your space. We want our own spaces. We want to be the producer, the director, the viewer. We want it in our own language—and I mean that metaphorically—languages that speak to us and come from us."

When we prepared for Venice, we worked hard on the catalog—which launched in August. It's a very dense catalog, and we made a real effort to bring in other partners to represent the diversity of Native American people. We exist under a single umbrella term in the United States, yet that term covers hundreds of tribal communities and distinct cultures. It's similar to how people sometimes refer to "Africa" as a single entity, when it's really 54 countries. Revealing the diversity within the terms "Indigenous" or "Native American" felt like the necessary next step.

I first started going to Venice in my 20s. Kathleen Ash-Milby, one of the co-curators, invited me on what was probably my second trip, in 2005. At the time, she was working at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City. Back then, they were putting forward proposals for Venice that didn't make it through as official national representations; they ended up as collateral projects. I remember our conversations—"What if one day this actually happens?"

I also heard the criticisms: the cost of doing a large project in Venice, and why that money shouldn't instead be spent in the communities, rather than abroad. So when I was selected, I knew it would be a huge mistake to just go as Jeffrey Gibson. I needed to bring people with me—physically, by invitation—and give them a platform to do what they already do, not to direct them or tell them what to make. This has long been part of my practice through performance and community-based events, and it made sense to bring that to a larger stage.

I didn't know that people would embrace the idea and support us to make it happen. As an artist, you’re always prepared to hear, "That costs too much; we need to scale it down." But I was fortunate—many people saw the importance. I also knew that attending the Biennale is not an experience many Indigenous or Native American people will ever have. So the images and documentation became essential: how the exhibition would live on, either through social media, in print, on people's phones, or in educational contexts. We created as many forms of documentation as possible.

Those images are especially important because they counter historical images of Indigenous people who weren't invited to Europe but were brought there. From day one, generating new imagery was one of my main goals.

Jelena Martinović: Now that your exhibition has moved from Venice to The Broad, how did the different context and space shape the way you reimagined the show?

Jeffrey Gibson: I didn't really think about it until I visited The Broad to see the space. There was this immediate realization: the weight of the Venice Pavilion—the context of Venice, of being a national representative—was suddenly gone. At The Broad, the audience is different. One of their initiatives is to bring in people who don't normally go to museums, so it's not necessarily an art-specific audience. That felt great. It was freeing. We already had the work and the murals, and we were also able to bring in a piece I really love from my 2020 Brooklyn Museum exhibition—a monumental sculpture called The Dying Indian.

I have to say, The Broad has done a great job with programming and with engaging Native communities in Los Angeles, particularly from Southern California. But for me, it was also important that my goal isn't to set up a new hierarchy with Indigenous people at the top. I go back to that 1990s vision of an intercultural space. The Broad also invited many non-Native communities and engaged them with the subjects in my work. The show is really about the many voices within American history.

So for me, showing the exhibition at The Broad felt very freeing. I walk in and recognize the exhibition, but it doesn't carry the same weight it had in Venice—and that's a positive thing. It feels like a release.

Jelena Martinović: At Venice, your pavilion challenged dominant narratives about American identity by centering Indigenous voices. How does your current exhibition at MASS MoCA, POWER FULL BECAUSE WE’RE DIFFERENT, continue or develop that conversation?

Jeffrey Gibson: It was interesting because that exhibition, the invitation, came to me from Denise Markonish six years ago, and at the time I wasn't doing these really large installations. I was still showing objects that were heavily crafted—paintings and smaller works. Denise and I really talked about how to create a space that wasn't about filling it with small, crafted objects, but something larger—an environment.

I think the book An Indigenous Present, which came out in 2023, and then Venice in 2024, were very specific contexts. MASS MoCA felt different. I wanted to think about what excites me. I gave myself as much freedom as possible.

The garments in the exhibition are central. I wanted them to fill the space with atmosphere. I knew light and video would be part of it because they allow a space to be filled without relying on material objects. From the start, I remember telling Denise, "It has to be somewhere between a church and a disco."

I was thinking about nightclubs in the late '80s—the way sound works, the darkness of the space, and that feeling of not being fully in view. In the dark, the way we relate to strangers can sometimes be more generous than in the light, where visibility can create discomfort. Sound works the same way—you feel it in your body. So in the main space at MASS MoCA, there's this thumping sound you feel physically. Then you walk into another space and suddenly you're in this bright, colorful environment, with the sound just in the background.

It's always important to me that the garments are worn. Lately, I've worked with other performers, but this time I thought—turning 50, feeling my body change—I wanted to wear the garments myself. These garments are about me. If someone else wore them, I'd just be directing, but I knew how I wanted them to move. The movements in the video are, first, an ode to Leigh Bowery, who has been a huge influence on me. And second, it's about a large brown body—a 50-year-old male body—existing in a space where identity is fluid. Is it camp? Is it real? Is it ceremony? It's this disruptive embrace of identity that isn't fixed.

Then I came across a 1991 documentary called Two Spirit People. I was 19 then, and I remember someone asking me if I was Two Spirit. At the time, I read it as a fetishistic term and said no, I didn't identify that way. But watching the documentary now, I saw that the individuals interviewed felt the term gave them language and recognition. It's amazing to see how a term can enter the world, grow, and evolve over 30 years—how it not only sticks and gains resonance, but also morphs as people personalize it. Many are now reclaiming this role in their home communities and finding the words within their cultures to describe it.

When I think about disruptions in Native American histories, Two Spirit is a term we can actually trace. It emerged around 1990, and that period is accessible—we can still speak to people who were there, and we can see the images. It's a living history. We don't have to accept the gaps; we can research, document, and build a timeline. For the video installation, I reached out to people I'd been following online—people I thought were cool and interesting. One of the joys of this work is being able to reach out and say, "I love what you're doing. Can we talk?" They contributed to the five-channel video exploring the concept of Two Spirit identity.

Jelena Martinović: The concept of Two Spirit identity features strongly in your MASS MoCA work. What new possibilities do you think this idea opens up when it comes to rethinking gender and community, both within Indigenous cultures and more broadly?

Jeffrey Gibson: I think, first, it counters this long-standing narrative of Native people as "uncivilized." That view is already antiquated, but some people still want to maintain it. Cultures often work hard to preserve the otherness of those they're othering.

The term Two Spirit, to me, presents Indigenous cultures as wise, accepting, civil, and intelligent. Who can say exactly how contested that role was at the time—but we know it existed. We have evidence. For example, if you see a textile historically woven for a Two Spirit person by a community member—that textile isn't just fabric the way we think of fabric today. It's a symbol of acceptance and care. That, to me, is beautiful.

Albert McLeod, who was there when the term emerged, once told me that the words Two Spirit acted as a portal. I found that so compelling. A word appears, and suddenly people recognize themselves in it—they say, "Oh my gosh, that’s me." They embrace it. The word spreads, and people feel seen and acknowledged through it.

Albert also said to me, "Your exhibition is a portal. Everything you’ve put in there is a portal." That resonated. I often stay in my own headspace when I'm making work. I don't necessarily have an agenda. I make the things I want to see and the things I feel from. So when people come into the exhibition and tell me they feel acknowledged or that the work resonates with them, it’s a tremendous compliment. It's not unexpected, but it's also something you can never fully predict.

Jelena Martinović: Collaboration seems central to this project. How did you approach working with other Indigenous artists? Were there any particular conversations that helped shape the exhibition?

Jeffrey Gibson: I'm always very cautious, because I never want to presume anything—just as I wouldn't want anyone to presume things about how I see myself.

For this project, I worked with Antonia Oliver, who helped me curate the resource room at MASS MoCA. She would arrange the calls. We would review videos together and decide which people we wanted to reach out to. Then she'd set up the call, and I would introduce the project and the work.

Some people already knew me as an artist, while others had never heard of me. But I was approaching them for what they do. I would say, "We've watched your videos online, and we're so excited by your work." Some of these people aren't thinking about the art world at all, which I actually love.

I'd often ask, "Do you identify as Two Spirit?" That always led to interesting conversations. Some people said no, but they would share the term for their identity in their own language. I love hearing people's stories—I get absorbed in them. So a lot of these calls were simply me sitting there, listening.

Everyone was paid a fee to borrow their content. And I say "borrow" because this piece will never be sold or made commercially available. If it's ever shown again, we'll renegotiate. This exhibition was a one-time agreement for use.

One thing I always made clear is: "You’ve already done the work." I wasn't asking anyone to create something new. This was an acknowledgment of who they already are and what they've already made. We think they're fabulous, and we just wanted to invite them to be part of it.

What came from it—well, in the video, and this is something I always explain to people—I'm ultimately treating the material like a kind of found object, collaging found material. I worked with a sound engineer, I worked with an editor. We sampled it, cut it, tried all sorts of things with it. So I needed their permission to do that. They're not there to sign off on what I do—they're agreeing to trust me.

That's also why the resource room exists: it gives visitors access to the full videos, so people can see some of the artist's work in its entirety. In the installation, we might use only 30 seconds of a 10-minute piece, but the resource room preserves the full context.

Working with the public, for me, is a practice in treating people the way I would want to be treated. The LGBTQ+ Native community has been incredibly open and welcoming. People have been fantastic.

Jelena Martinović: The garments in the installation are hung from teepee poles, which suggest both ceremony and movement. Can you talk about how those structures work within the space, especially in relation to performance?

Jeffrey Gibson: I did offer all of the collaborators who came into the space the chance to perform in the garments, and anyone could wear them, but they're not made with any sense of practicality. They're huge and difficult to move in. For instance, on someone your size, you'd need help just to walk across the room. And to me, that's fantastic. The performance of wearing them requires other people—you need help to move, to coordinate, to communicate. Even when I wear them—and I'm six-foot-two—they're big and heavy, and I need assistance to navigate the space.

The teepee poles came from thinking about the problem of mannequins. When you make a garment, you immediately think of clothing on a human body, but I wanted to avoid that. I didn't want these to be about representing a body. I wanted the garments to function as their own bodies. So the poles allow the garments to be raised and lowered, evoking ceremonial regalia that's only worn at specific times and then stored away. Suspended above you, they take on this angelic, almost spiritual presence, hovering in the space.

I also want to be clear: I'm not making ceremonial garments. I'm making artworks. People have asked me, "Why don't you call them ceremonial?" And I've even had someone say they felt the piece represented their spiritual self. If they asked to wear it, of course I would consider it an honor. But I think of these garments as nexuses—bringing together different narratives and practices.

One of my biggest influences is Magdalena Abakanowicz. The first time I saw her fiber sculptures, I thought, "What an amazing structure to inhabit." I also look at avant-garde fashion—like Rei Kawakubo's couture gowns—which challenge the very shape of the body and ask how fabric can transform it. And, of course, Native American regalia has always inspired me: it's meant to move. Whether through sound, ribbons, or fringe, it extends the body's movement, creating shape, color, and rhythm in motion.

All of these influences funnel together in my process. These garments take a long time to make—seven garments took about 18 months with a full team working on them. It's always a race against time, but I love that intensity of process and craft.

Jelena Martinović: I'd like to return to something you mentioned earlier about representation in the art world. How do you see the difference between representation and inclusion playing out today?

Jeffrey Gibson: Representation and inclusion? That's an interesting one, because it's easy to assume they work in tandem, but I don't think they do. Sometimes, representation feels like bait. Representation can become a temporary theater of inclusion—it doesn't necessarily reflect meaningful change within the institution.

Inclusion, on the other hand, is about inviting people in and listening to them. You're not diluting or dismissing their input; you're taking direction from it. Whether it's a critique or a proposal, you actually implement what they share.

I often find myself having to explain my work through a cultural narrative—almost trying to convince someone that it's real or important. But institutions don't need to fully understand everything. It's like being in a relationship: if one person constantly demands explanations, it becomes almost abusive. If someone says, "I'm in pain," the response should be, "Tell me what's causing your pain and how I can help." That's the difference between representation and inclusion—one keeps a barrier of othering; the other allows for trust and collaboration.

Jelena Martinović: What challenges do you think institutions still face when engaging with artists from historically excluded communities?

Jeffrey Gibson: Lately, I've been thinking a lot about legibility and illegibility. I sit on a couple of boards, so I hear many institutional conversations. I'm not anti-institution—there are many I respect—but I do think the way they engage with historically excluded cultures needs to broaden and evolve.

By legibility and illegibility, I mean this: imagine being a child arriving in a foreign country. You don't speak the language, you've never tasted the food, you smell things you've never encountered. You can't fully comprehend what's happening—but that disorientation can instigate a sensorial way of learning and experiencing.

That feeling of embracing the unknown is powerful. People are afraid of the unknown, but as an artist, you learn that going into unknown territory is essential if you want to create something new. Institutions need to embrace that counterintuitive skill: to be quiet long enough to absorb what they don't understand, to hand over power, and to allow the experience to change them. And to truly allow it to change you—that's the key.

Jelena Martinović: Finally, with ongoing political struggles around the world, what role do you think art can play in advocacy and social justice? How do you see artists contributing to tangible change through their work?

Jeffrey Gibson: I think it's a really interesting question. I've been an educator for more than 20 years, and over that time there have been moments when students have refused to work and said, “Why make art when the world is in crisis?”

In response, I invited two people into my classroom for conversations—Avram Finkelstein, one of the founders of Gran Fury, and AA Bronson. I asked them: when the AIDS crisis hit, what was the role of your work? Now, we look back at that moment and view their output as successful political art. But I wanted to know: in the moment, how did it come about?

What I learned from those conversations was that they were already deeply engaged in their communities. They weren't suddenly politicized. They were already making work about the people and the issues around them. So when the AIDS epidemic hit, and people in their communities began dying, their work naturally reflected the crisis. That wasn't a pivot—it was a continuation.

So when we ask how art operates politically, I don't think it's usually about suddenly deciding to become political. Although, maybe for some people it is. But generally, it's about how you're already engaging with the world—how that engagement becomes more urgent or heightened in moments of crisis.

There are many forms of engagement. There’s direct activism, yes. But there are also those who choose other paths. For example, I think a lot about Black American artists in the 1960s and '70s who continued working abstractly, even amid major civil rights struggles. I'm so grateful they held onto that practice of experimentation.

I've been thinking about why I admire that decision so much, and I think it's because they kept a space open—a space that could have easily become narrowed or didactic under pressure to “represent” in certain ways. Their refusal to collapse their practice into something easily legible created room for complexity, for ambiguity. And that matters. Race, identity, belonging—these are not questions with simple answers. And their work reflected that truth.

So between those two examples—direct political art and abstract, introspective art—you get a kind of spectrum. Both are valid. Both offer different ways that art can affect people, shift perspectives, and create space for imagining what comes next. We need that. Desperately. Not just beauty for beauty's sake, but a way to tap into something essential about being human—something beyond survival, beyond reaction.

Disruptions will continue to happen. They're part of living. What matters is how we move through them. How we continue to imagine solutions. How we insist on pursuing humanity—on staying humane.

There was a conversation I heard once—I can't remember exactly when or where—but someone said: "Imagine history without art." And to me, that's a horrendous thought. I wouldn't want to live in a world without music, without visual language, without something that allows us to express or understand feelings and experiences that we don't yet have words for. That's what art does. It enables us to imagine.