Remembering the Nakba in Sheffield, 2024. Photo by Montecruz Foto, Creative Commons

Remembering the Nakba in Sheffield, 2024. Photo by Montecruz Foto, Creative Commons Middlesbrough Art Week 2025 (MAW25) returns from September 25 to October 4 with an ambitious program of exhibitions, performances, workshops, and public interventions, transforming the town into a platform for dialogue, creativity, and collective reflection. Built on collaboration and community, the festival spans galleries, streets, empty shops, and project spaces, emphasizing accessibility and inclusivity while giving artists space to experiment with socially, politically, and environmentally engaged practices.

Under the theme In All Possible Worlds, MAW25 invites audiences to imagine futures shaped by resilience, creativity, and shared human experience. Among its diverse program, Platform Films' Censoring Palestine (2025) exemplifies the festival's commitment to work that interrogates power, memory, and representation, examining how political institutions, media, and social pressures conspire to silence dissent.

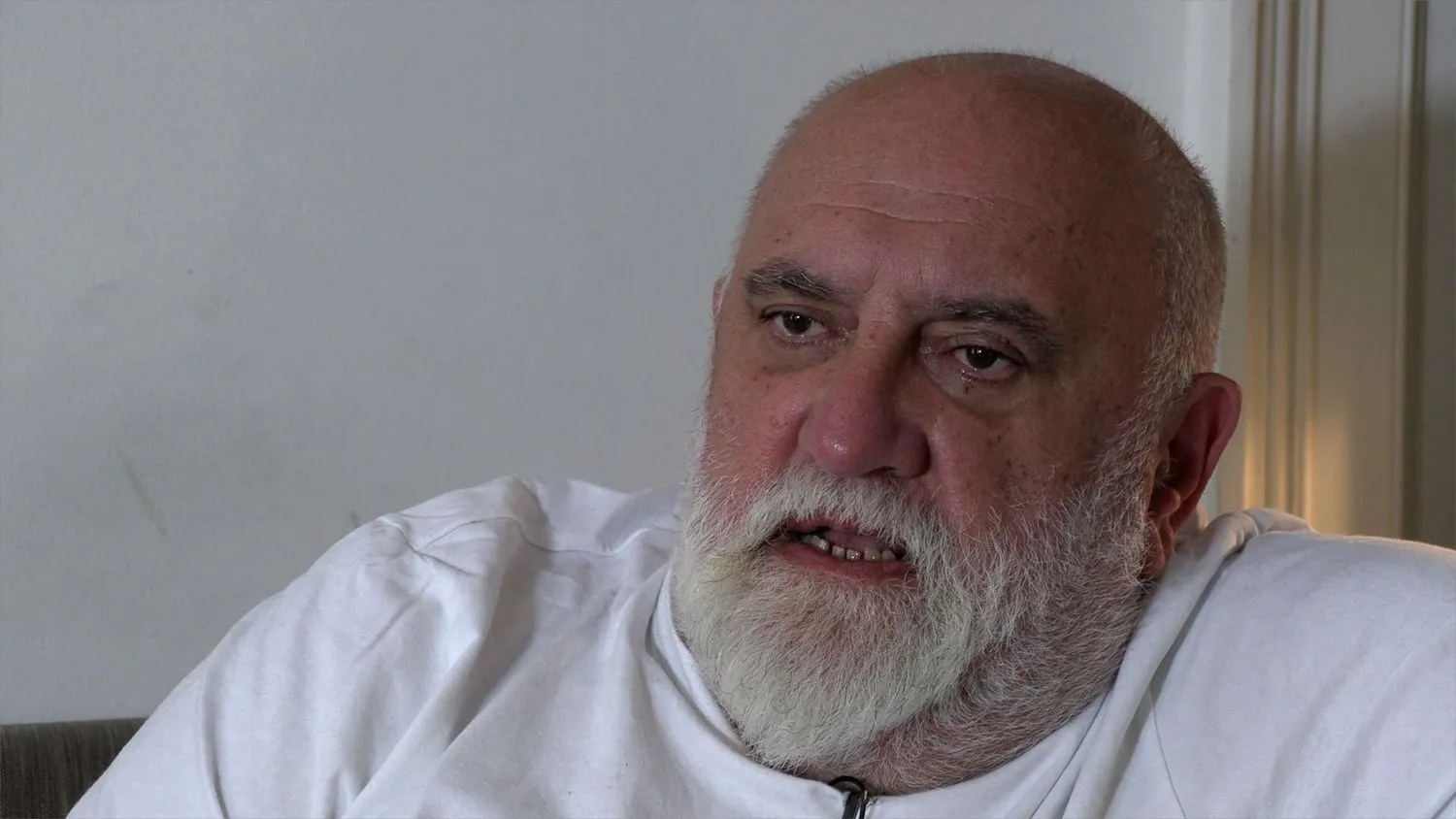

For over five decades, Platform Films has carried forward the tradition of left-wing filmmaking, producing documentaries that foreground political struggle, social injustice, and the voices often silenced in mainstream media. Emerging from the pioneering Camera Action group of the 1960s, the collective has remained committed to supporting workers, trade unions, grassroots movements, and communities whose experiences challenge dominant narratives. Platform Films, led by Chris Reeves, Ann Diego, Christine Tongue, and Norman Thomas, has built a substantial archive of radical cinema and continues to produce new films that engage urgently with contemporary political and social crises.

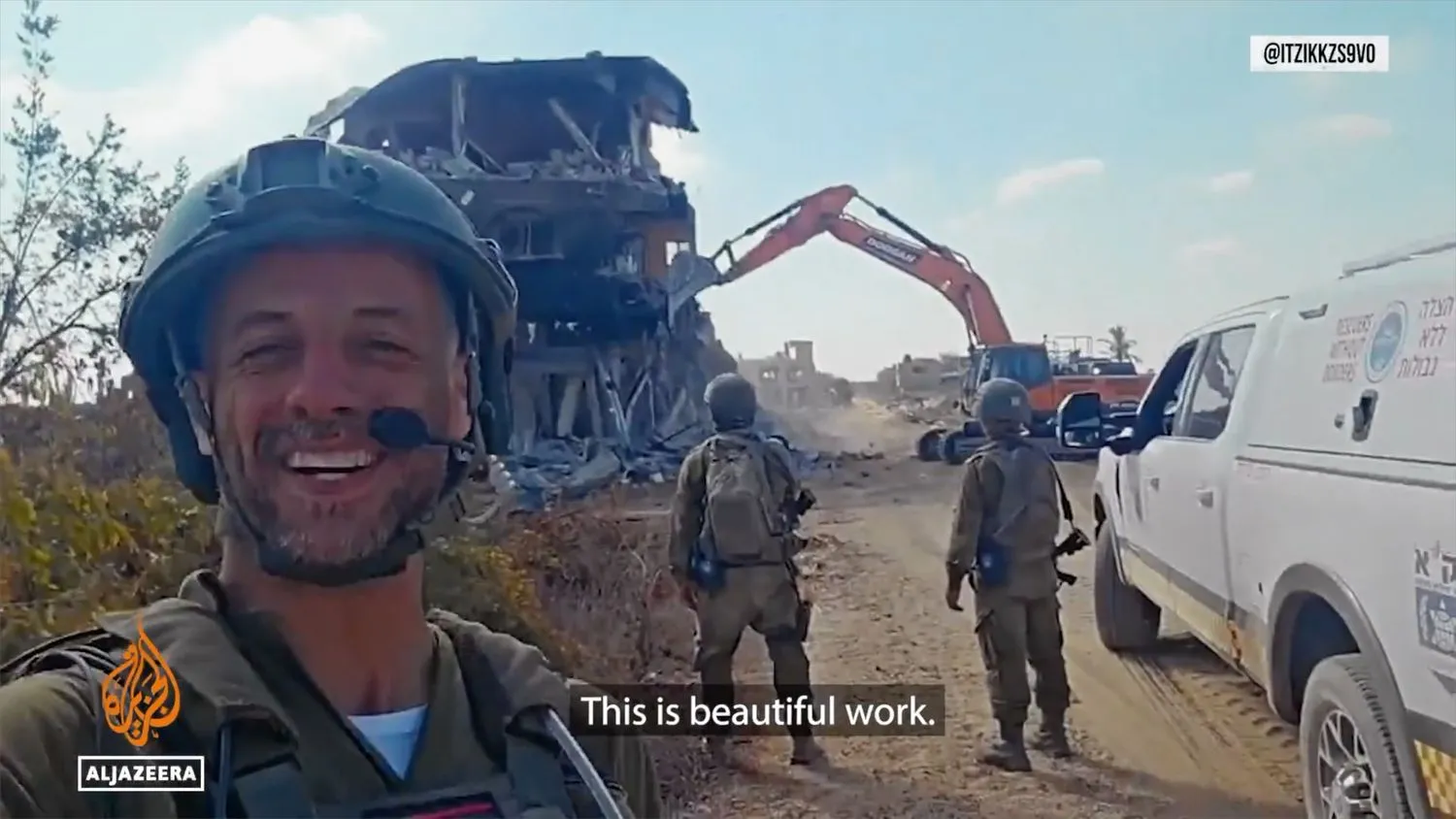

Its latest project, Censoring Palestine (2025), tackles what Thomas calls the most glaring instance of suppression since the downfall of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn: the systematic denial of Israel's genocide in Gaza by political institutions, media outlets, and cultural platforms across Britain and beyond. The film examines censorship across newsrooms, education, social media, and the arts, while also highlighting the corrosive effects of self-censorship, where fear of professional or personal consequences deters people from speaking at all. Featuring voices such as Ken Loach, Jackie Walker, and Alexei Sayle, it builds on Platform's earlier film Oh Jeremy Corbyn – The Big Lie yet expands the inquiry to the structural silencing of Palestine solidarity in public life.

In this conversation, Thomas reflects on the ethos behind Platform Films' decades-long practice, the challenges of producing politically uncompromising work with scarce resources, and the risks of confronting entrenched power. He speaks of Censoring Palestine not simply as a documentary but as a necessary intervention — an attempt to resist despair, sustain truth-telling, and inspire collective action at a time when, as he puts it, "the global establishment has never been more desperate to preserve a crumbling world order."

Jelena Martinović: Platform Films has carried forward a tradition of left-wing filmmaking for decades, working to raise political and social awareness and inspire change. What ethos guides the stories you choose to tell?

Norman Thomas: We look for stories which are politically powerful and revealing in their own right, such as the downfall of Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, or the suppression of the truth about the genocide in Gaza in the mainstream media, but which also inspire viewers to take constructive action to improve the situation. We want to show the reality of what's happening but we do not want to spread despair.

JM: Platform Films produces its own documentaries, curates a major archive of left-wing films, and collaborates with trade unions, movements and organizations. How do these different strands of work inform each other and shape the stories you bring to audiences?

NT: My own view is that this group was dedicated to giving a voice to workers, to the working class and disadvantaged people. Platform's documentary work, its collaboration with trade unions and other organisations, and its archive of left-wing films all seem to me to follow that example. They come together with one main aim: to help raise people's political consciousness and offer a critical alternative to a mainstream media which overwhelmingly — and destructively — tries to serve the interests of the political establishment.

Platform is now rapidly adding to its store of left-wing material with shorter videos — for example covering the protests against the genocide in Gaza — which we are releasing on YouTube as soon as we can, sometimes even on the day they happen. I think this is exactly the kind of thing which left wing activist filmmakers such as Camera Action would have done if the technology of their day had permitted.

The upshot of this is that Platform Films now has a large and ever-expanding body of material, the component parts of which all inform each other and together comprise a sort of great left wing "memory" which we more or less draw on automatically in making our films and which, I hope, helps us make films which are more accurate, more effective and more authoritative.

JM: Following your film Oh Jeremy Corbyn – The Big Lie, which examined how media and political forces undermined the Labour leader, Censoring Palestine appears to continue this investigation into censorship and suppression, but in a broader societal context. What led you to focus on Palestine and how do you see this new film building on or differing from the work and approach of the earlier project?

NT: What led us to focus on Palestine in our latest film was that it was simply the most glaring example of censorship and suppression since the downfall of Jeremy Corbyn and, unquestionably, much worse since it involved the mainstream media ignoring and denying a genocide and not just the destruction of a political party.

Censoring Palestine does absolutely build on Oh Jeremy Corbyn – The Big Lie because I believe it demonstrates with terrifying clarity the motivation of one of the strongest forces behind Corbyn's downfall — the pro-Israel lobby. The forces supporting what Israel is now doing in Gaza could never accept the possibility of a pro-Palestinian prime minister in Britain.

Unintentionally, Censoring Palestine now seems almost like a tragic sequel to Jeremy Corbyn – The Big Lie. If our films turns into a trilogy I hope the third instalment provides some kind of positive resolution, but currently this seems extremely unlikely.

JM: Making and distributing a film like this carries risks — politically, financially, even personally. What challenges did you and your team face in bringing it to completion?

NT: We faced many challenges in making Censoring Palestine. Making documentaries on a political question means you're inevitably faced by the endless factionalism of the left. Infuriatingly, this means some people refuse to be interviewed because they see themselves on the other side of a political divide. But in making this film the vital need to confront the horrors of the censorship of a genocide for most people transcended any partisan or ideological rivalries.

The personal and financial challenges of making and distributing the film were much tougher, I feel, and were inextricably linked. There was never enough time in the day to undertake all the filming and editing required nor any secure sources of finance to pay for people's time. Donations were accepted but these barely covered the film-making expenses and meant that most work was undertaken on a voluntary basis and costs had to be borne either out of people's pockets or in the hope of some recompense down the line. The personal strain this put on those involved was, of course, tremendous. Only the daily horrors of what was happening in Gaza spurred us on to continue.

JM: Censoring Palestine looks at censorship across society, including media, education, social platforms, and legal mechanisms. What patterns or broader systemic dynamics became clear as you investigated these different arenas?

NT: This question is at the heart of the film and definitely needs further investigation. Short of some incredible conspiracy, how can we account for the media, educational establishments and many other organisations all attempting to use their powers to suppress the truth about what was happening in Gaza?

The starting point, it seems, must be the mainstream media who were motivated by their political agenda, totally aligned with the intertwined forces of the government, the British establishment, the so-called "Transatlantic Alliance" and the Israel lobby.

When there are enough powerful forces pointing in the same direction — the support of Israel — then standing against them is a mighty task and it's a huge tribute to the pro-Palestine protest movement that they have continued despite it all. But how exactly this all works and what it tells us about the nature of our society is a big topic which we hope to cover in another film.

JM: The film weaves together a range of voices reflecting experiences of censorship and repression. How did you decide whose testimonies to include, and how did you approach presenting them?

NT: Out of the many people we contacted, very few people were prepared to speak about this subject for reasons easy to understand — mainly their careers and the fear of being branded antisemitic — so that straight off restricted the numbers of testimonies we had to choose from.

At the end of the day, the two decisive factors in choosing people to interview was (one) how well they reflected different aspects of censorship, so that we could give a reasonable account of the wide and diverse way censorship has made itself felt, and (two) their readiness to be outspoken and speak of their real personal experience of censorship — Ken Loach was maybe the ideal example of that.

Censorship has the potential to cause great emotional damage on its victims and we naturally made getting that across in the film a high priority. This was not at all something additional to the political aspect of the film but an integral part of it.

Like in the George Orwell novel 1984, censors will stop at nothing to preserve their version of reality, however distorted or unreal that reality may be and an awareness of that informed the way we presented the testimonies of our interviewees. In the process we hopefully, effectively dramatised our documentary in a way that a bare account of the facts of censorship would have achieved.

JM: The film also touches on self-censorship, where repeated rejection or suppression can lead creators not to propose certain projects at all, as observed by Ken Loach. How do you see these pressures affecting artists, filmmakers, and other creative professionals?

NT: Self-censorship is maybe the most insidious form of censorship because, by its very nature, we have no idea of how widespread it is. But, it appeared to me, that on the subject of the genocide in Gaza, self-censorship has been extremely widespread and has undoubtedly continued.

Many people we interviewed for research purposes but did not actually film were obviously fearful of even saying the word "genocide" in case they incriminated themselves. Obviously, this has applied to journalists across the mainstream media, but less obviously this has applied to creative professionals who have avoided the subject simply for the sake of a quiet life. As we discovered while interviewing a painter about censorship in the art world, it's hard enough to get your work exhibited with all other conditions in your favour, without adding an extra handicap such as choosing a highly controversial subject.

JM: Several screenings of the film itself have reportedly been blocked or pressured. How do you see this 'meta-censorship' illuminating the very dynamics the film explores?

NT: Yes, the film has been blocked and people have faced problems organising screenings. Really, this is only what we expected, given that the film was about censorship. We have no idea how many cinemas failed to take it up. It's easy to reject a film on the basis of having no room in schedules without admitting the real reason is the controversial nature of the subject matter.

On the other side of the question, our film has perhaps picked up additional screenings because of the wide and uncompromising pro-Palestine protest movement which our film has featured and is, in many ways, part of. So it's swings and roundabouts.

JM: The film is being shown as part of Middlesbrough Art Week. What does it mean for the film to be part of an arts programme, and how do you hope this setting influences the conversations it sparks?

NT: Some people would argue that a documentary film such as Censoring Palestine is essentially just a piece of journalism and therefore not art at all. But I would say, though, that the kind of work which goes into a film like this — for example, the choice of images and spoken words, the montages and the use of music — but also the extraordinary political context which has shaped it more than qualifies it to be part of an arts programme.

We live in a special time when the global political and corporate establishment have never been more desperate to try to keep a crumbling world order in their grasp. This establishment spends vast sums on a mainstream media which goes beyond the news and current affairs programmes into the world of entertainment and social media and beyond — a media dedicated to persuade people that lies are truth and truth lies.

Documentary film-makers such as Platform face the challenge of refuting and discrediting this media, not just by exposing the facts behind the fiction but by presenting things which are happening in the world around us which are ignored or marginalised in the mainstream media, the stories that aren’t told, the huge protests that don't get coverage.

Far from being "just journalism" our documentary films are, I believe, a very special art form created to find ways to cut through jungles of fake news and social media silohs to make an impact on the consciousness and conscience of all those prepared to open their eyes to what's happening in the world.

I welcome the opportunity for visitors to Middlesbrough Art Week to watch Censoring Palestine to judge whether they consider it art or not, and even more importantly, to start the kind of conversations the film was designed to provoke.