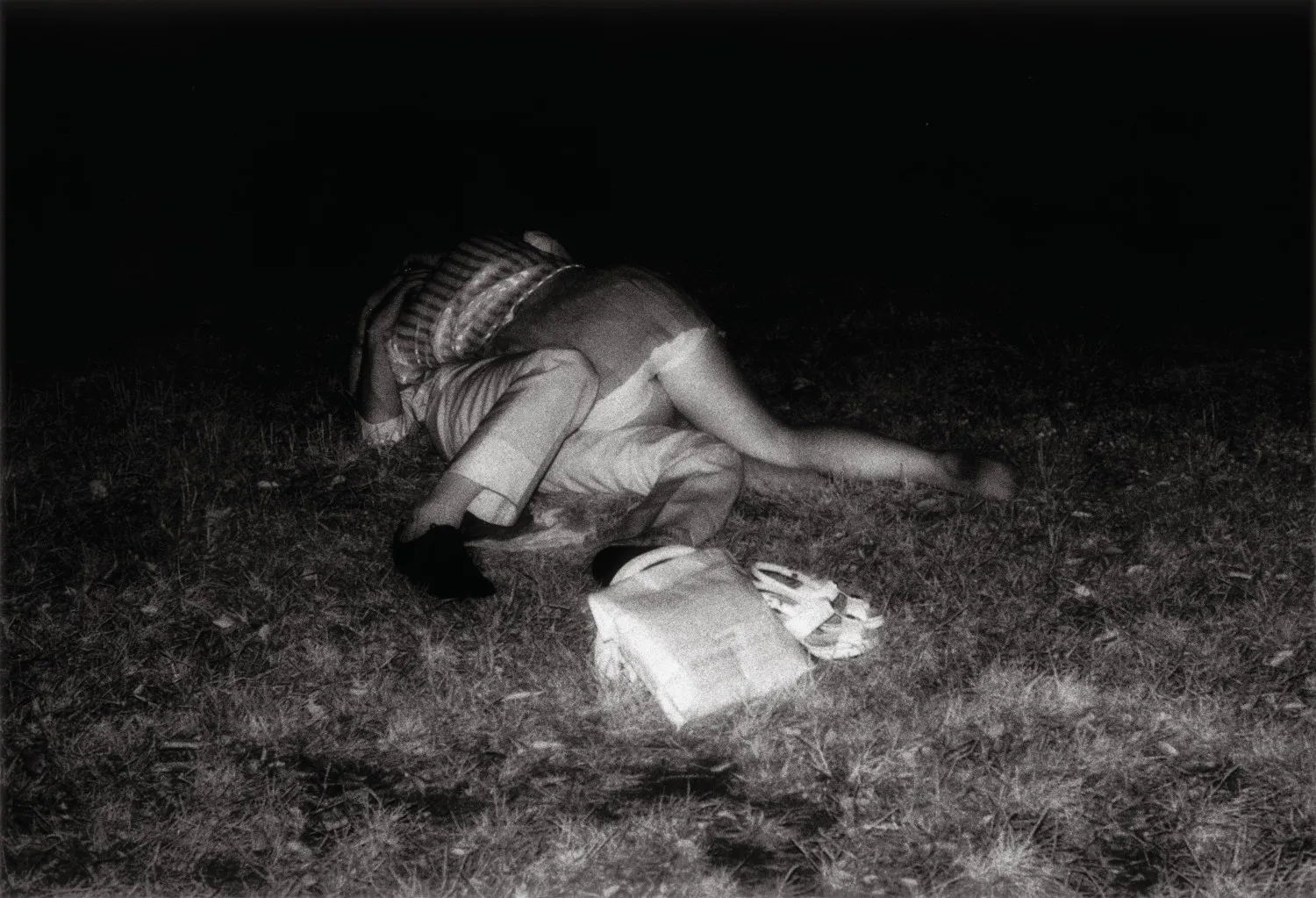

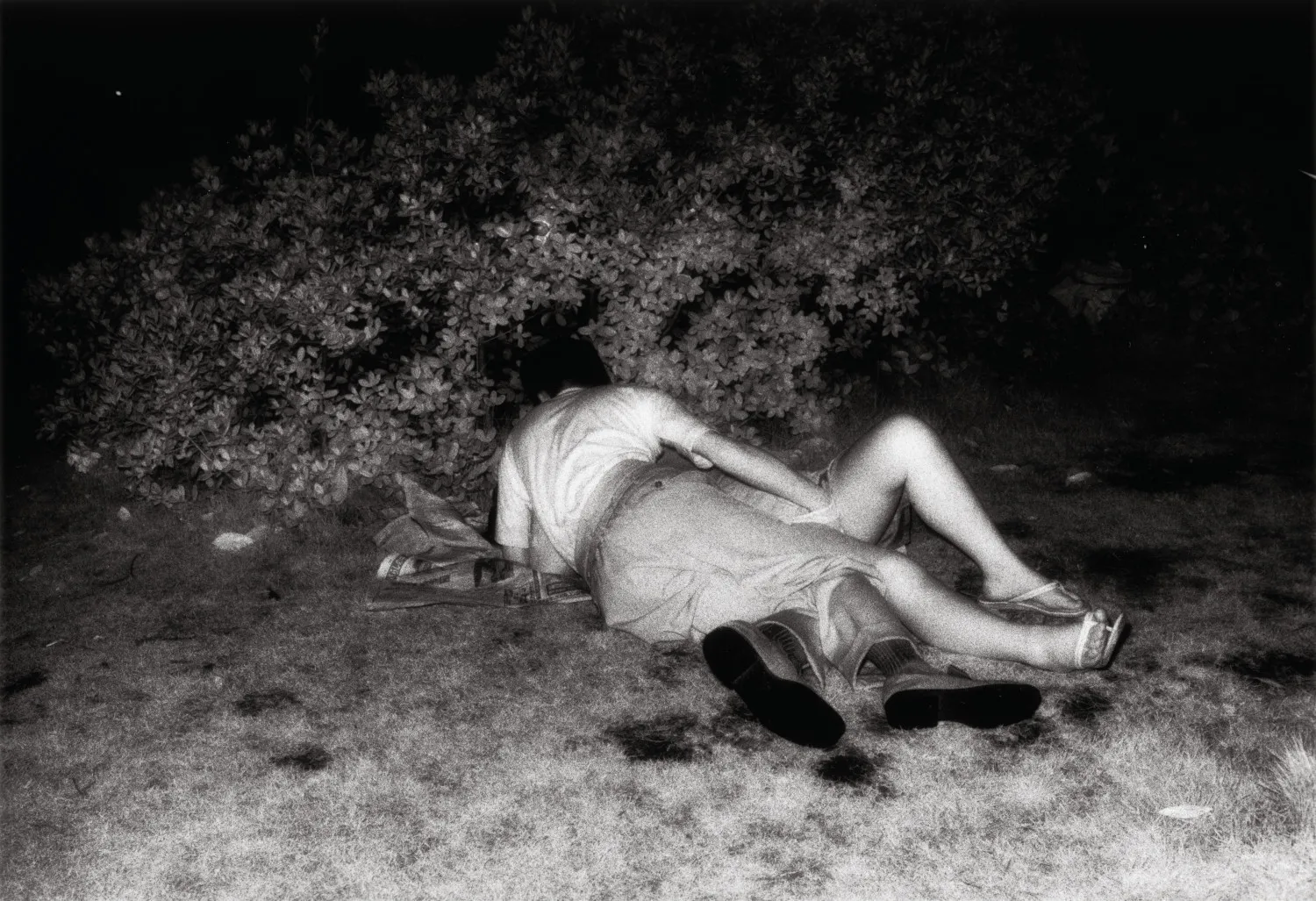

Kohei Yoshiyuki, Untitled, 1973. Gelatin Silver Print © Kohei Yoshiyuki, Courtesy Yossi Milo, New York

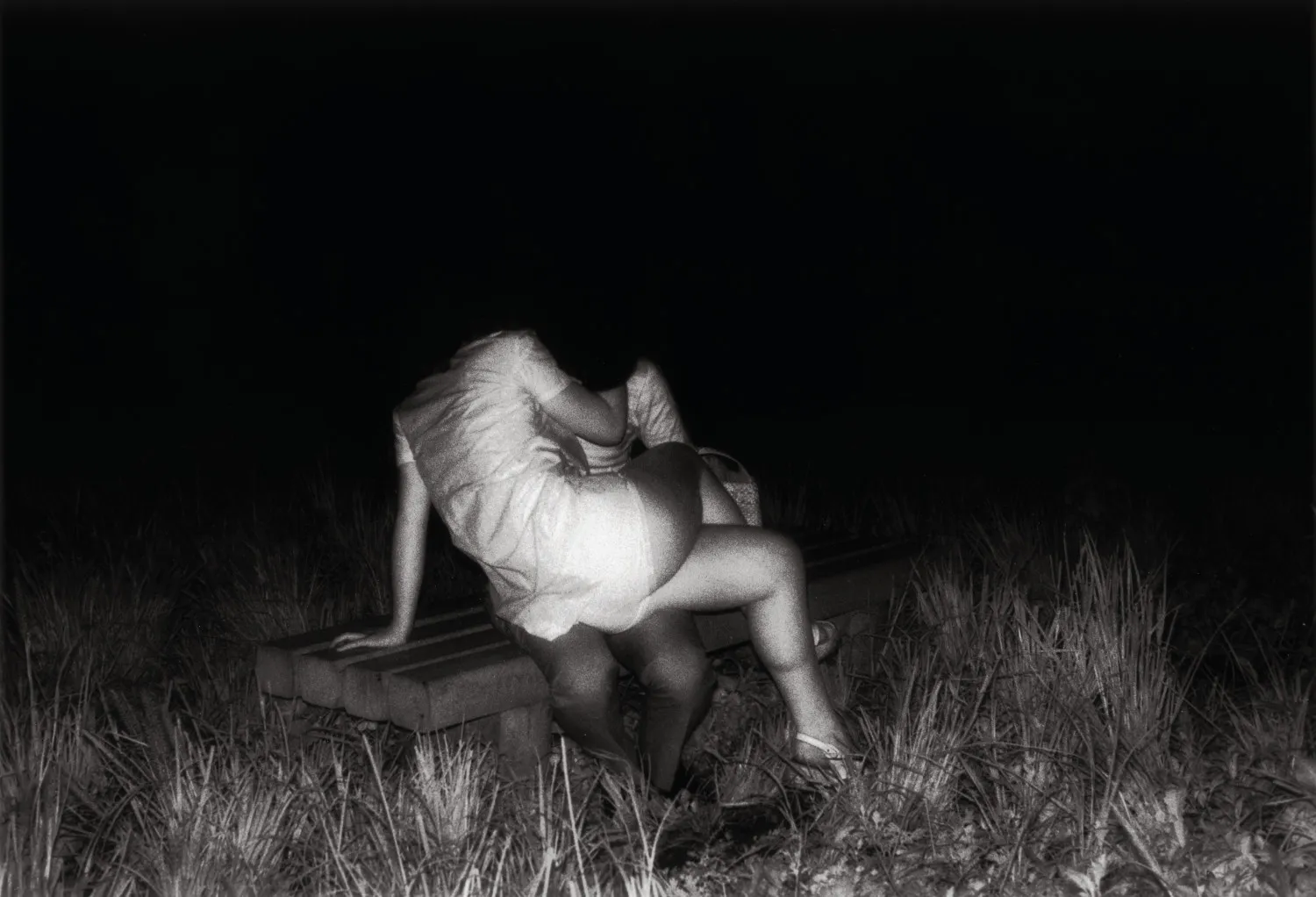

Kohei Yoshiyuki, Untitled, 1973. Gelatin Silver Print © Kohei Yoshiyuki, Courtesy Yossi Milo, New York In the period after the Second World War, Japanese photography developed a highly unconventional and unique visual language that laid the groundwork for contemporary Japanese art. Kohei Yoshiyuki's The Park, a controversial yet pivotal series capturing shocking nocturnal scenes, perfectly illustrates the paradigm shift of the period that became known as one of the highest points of innovative camera work in the twentieth century.

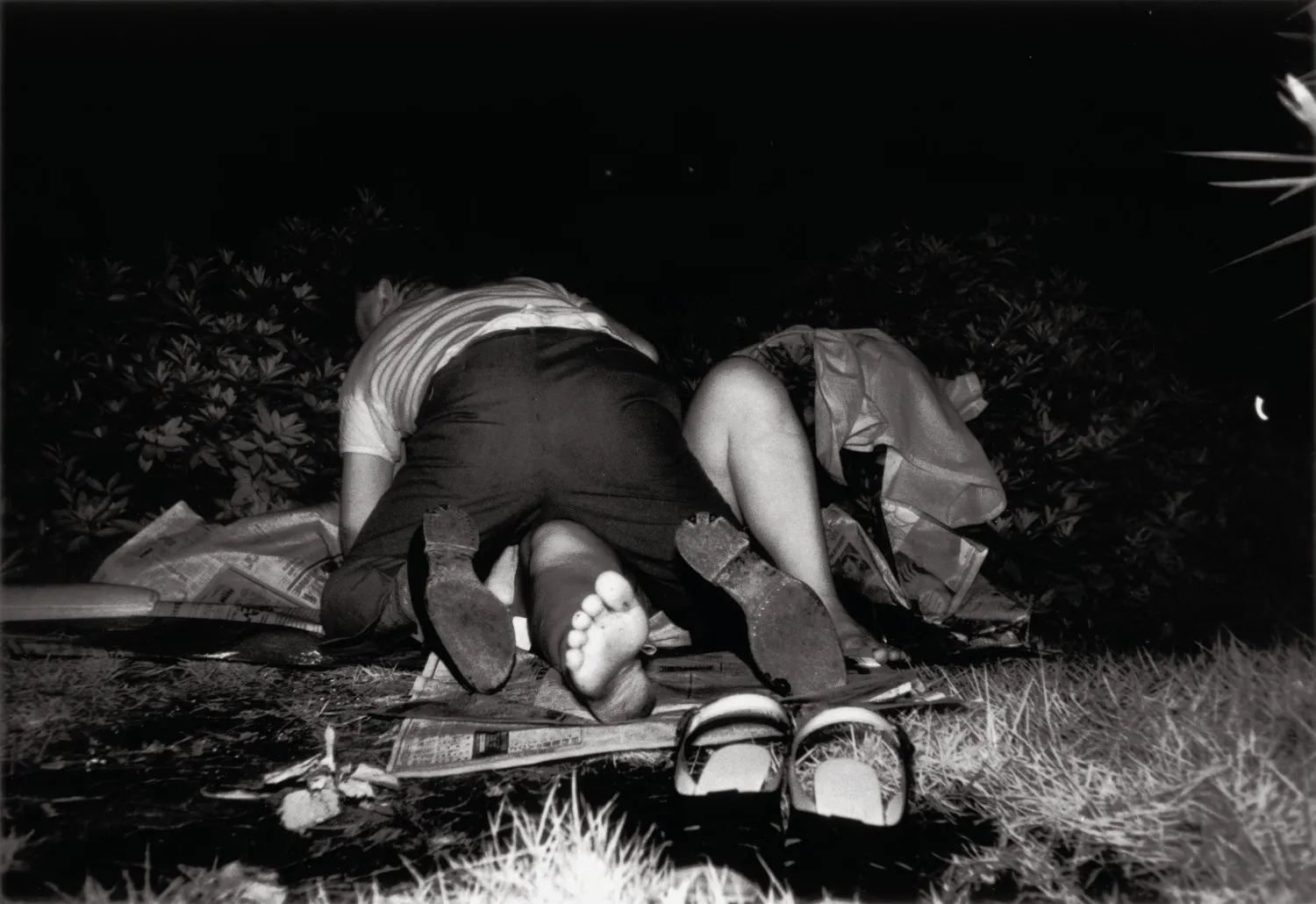

Yoshiyuki's lens chronicled the clandestine gatherings in Tokyo's parks after nightfall—moments of intimate rendezvous amid an audience of spectators lurking in the bushes. Raw, voyeuristic, and unsettling, these images document not only the couples seeking secluded encounters but also the onlookers, who observed and occasionally even engaged in these acts. While initially stirring controversy upon its 1979 exhibition and publication in Tokyo, The Park gained global recognition nearly three decades later, in 2007, with exhibitions across the US and Europe.

During the societal upheaval of the 1960s in Japan, a wave of artists and photographers embarked on diverse avenues to reflect the imminent cultural revolution. The camera became a mirror to this new Japanese society, becoming a potent instrument for artists to explore their subjective experiences within this shifting reality. This epoch, characterized by daring photographers redefining the medium, came to be recognized as the golden era of post-war Japanese photography. Kohei Yoshiyuki, a young commercial photographer at the time, produced a series known as "nominally a soft-core voyeur's manual."

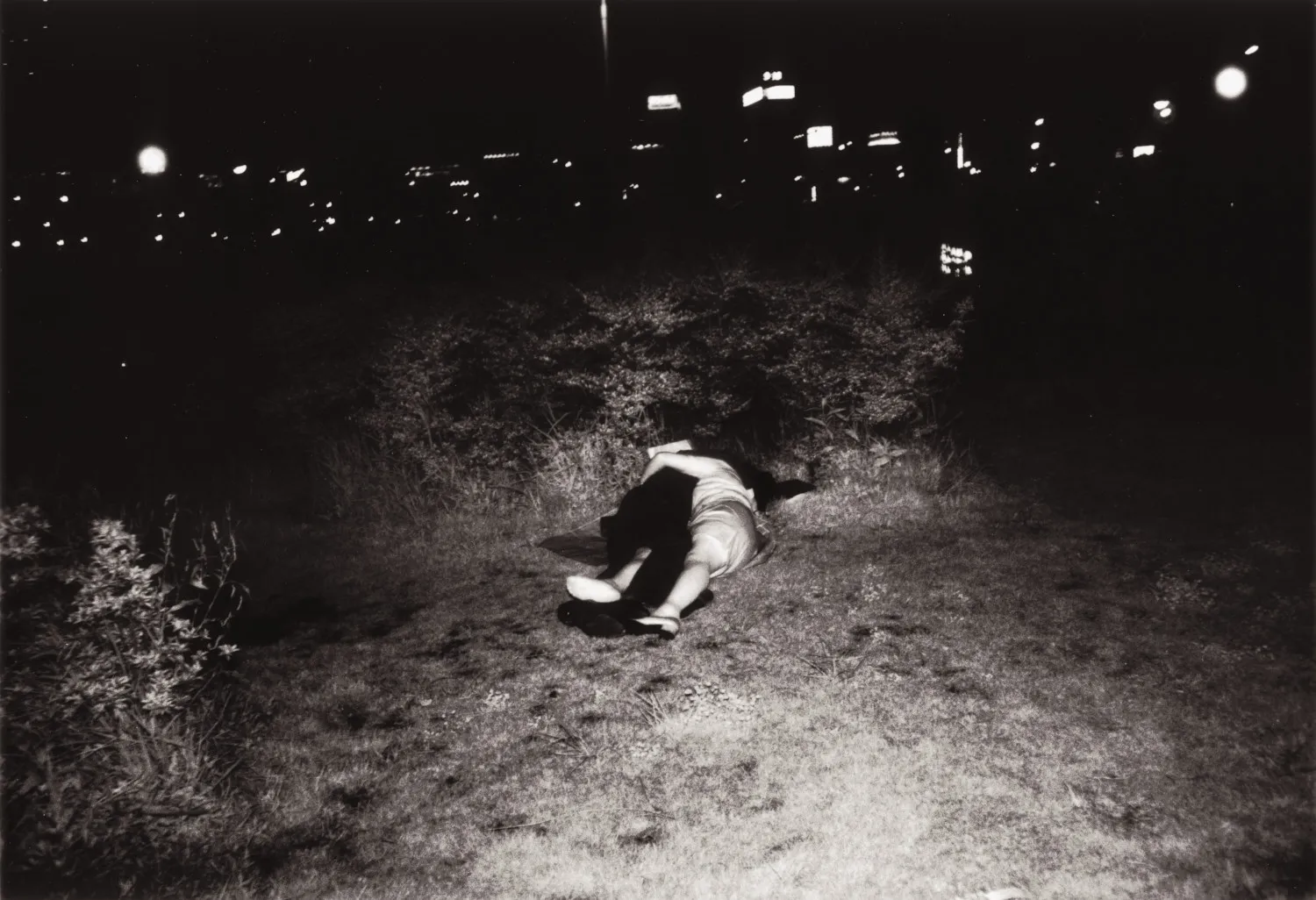

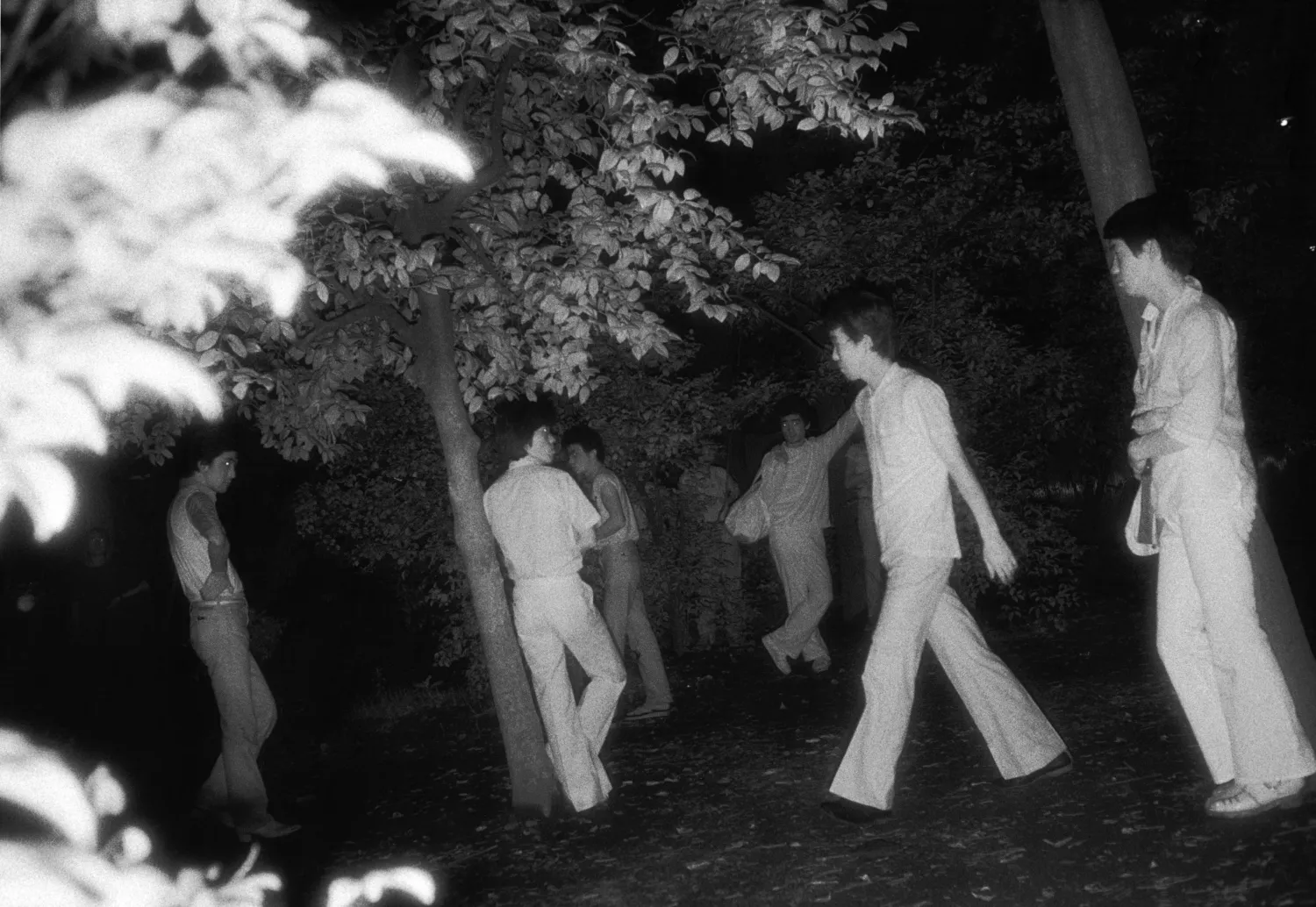

While strolling through a Tokyo park in the 1970s, Yoshiyuki stumbled upon couples using the park's darkness for intimate encounters. Yet, what drew his attention was not the act of spontaneous lust but the numerous lurking spectators who watched—and sometimes even attempted to take part in— these couplings. As a vital part of the city, parks were rare blind spots in the urban jungle where people could behave freely. What was a relaxing family place during the day would become a completely different world at night. These scenes veiled in darkness, which blurred the line between spectatorship and participation, fascinated him as a whole.

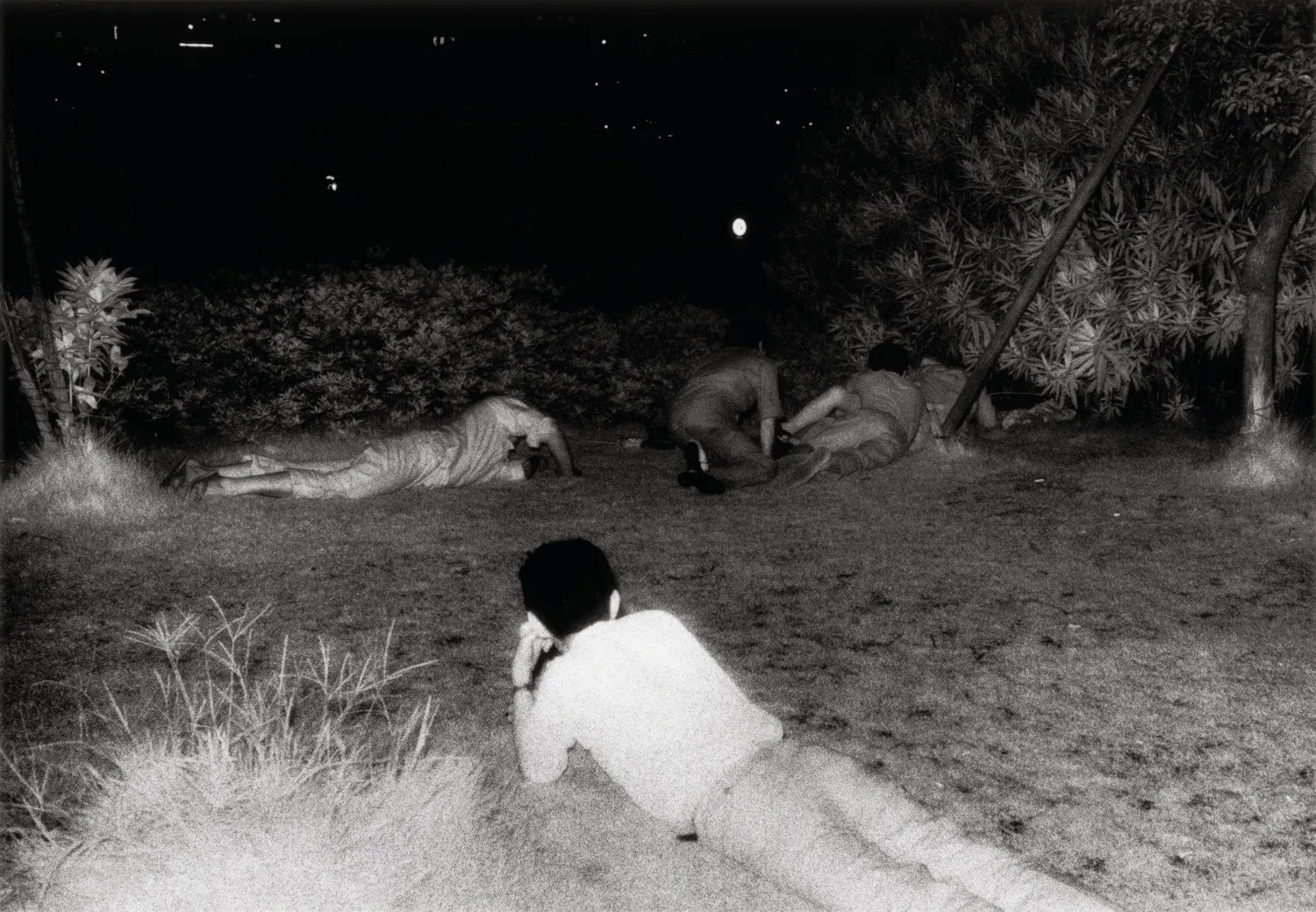

Prior to embarking on this controversial project, Yoshiyuki dedicated several months to perfecting techniques and equipment to capture these scenes in the dark. Using an infrared strobe, a then-expert-level photography method, and strategically inserting himself into this network of night-time voyeurs, he navigated through Shinjuku Central Park, Yoyogi Park, and Aoyama Park in downtown Tokyo. "To photograph the voyeurs, I needed to be considered one of them," Yoshiyuki explained. Working on this series between 1971 and 1979, he meticulously documented numerous couples, both heterosexual and homosexual, engaged in various degrees of intimacy. Capturing a marginal lifestyle in a discomfiting close-up, he created a haunting series that challenges conventional perceptions.

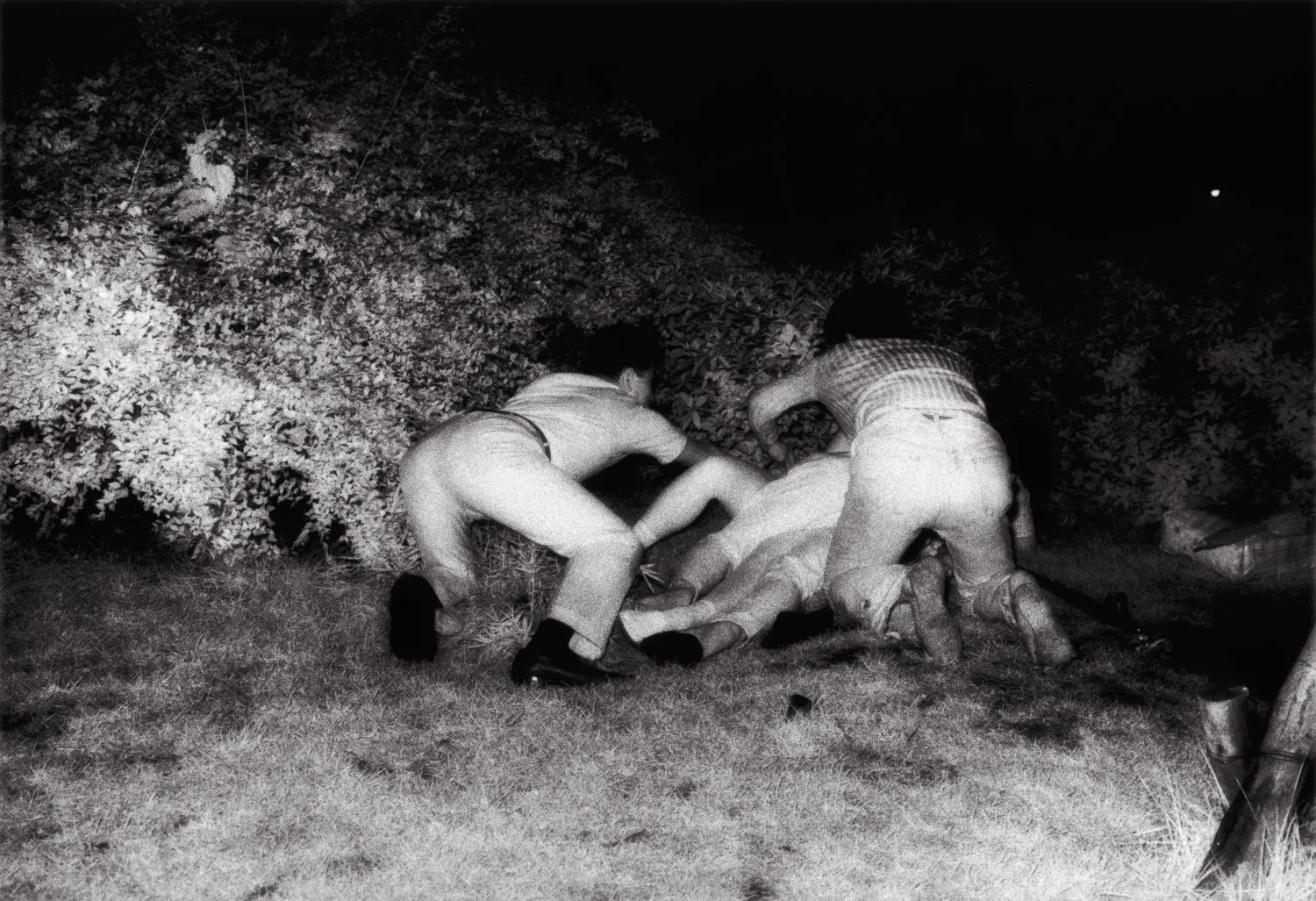

Images from the series speak of an underground scene that comes to life at night—a world of silk shirts, flares, grass stains and flashbulbs illuminating hazy figures in the dark. Images are blurred and we can vaguely see the bodies of people who are engaged in clandestine trysts. It is this invisibility that invites viewers to fill in the gaps, sparking their imagination. Rather than only depicting the couples, Yoshiyuki took a step back to capture the bizarre dynamics between voyeurs and the subjects of their gaze. The presence of the packed crowd of aroused observers surrounding the protagonists and occasionally closing in in an attempt to participate is what adds to the tension of this eerie and clandestine atmosphere. We see shadowy figures lurking within the darkness of the bushes, hands reaching out towards entangled bodies on the ground or even sly and abusive groping.

The exact nature of these invasions—whether entirely unexpected, anticipated, or simply predatory—is perpetually ambiguous. In his essay in the 2019 edition of The Park, critic Vince Aletti observed that these scenes suggest a ritualistic quality intertwined with a sense of chaos.

There's nothing romantic about this. Because everyone is bent on his own pleasure (her pleasure was another matter; it could not have been much fun for the women involved), the atmosphere in many of the pictures is dangerously feverish; several gatherings appear to be on the verge of a gang bang. If there’s a ritual, religious quality to some of these scenes, others are spinning out of control. The voyeurs stop looking like peep-show geeks and start to resemble shades in Dante’s Inferno.

There is a dark thrill in seeing these photographs, coaxing viewers to grapple with their complicity in observing intimate, covert moments. With their grainy, unrefined quality resembling surveillance footage, they immerse viewers into a complex dynamic of looking and being looked at. Set in dimly lit scenes, these images prompt viewers to peer closer, creating the sensation of being one of the lurking voyeurs captured in the images. Yoshiyuki's intensely involved point-of-view compels viewers to confront their own voyeuristic tendencies, enticing them to navigate the ambiguous boundaries of privacy, intimacy, and intrusion. This intriguing interplay redirects the gaze inwards, inviting introspection about the act of looking and its ethical dimensions.

Yoshiyuki's images unveil a hidden Tokyo, liberated from the constraints of daytime life by the shroud of night. Situated in a specific moment in Japanese history, these images reflect the economic and social realities of 1970s Tokyo, highlighting a lack of privacy in the bustling urban environment. These photographs primarily centered around Chio Koen Park in Shinjuku. This district, a hotbed of political activism and emerging sexual liberation, also attracted photographers like Shōmei Tōmatsu, Daidō Moriyama, and Nobuyoshi Araki, eager to capture their generation’s zeitgeist.

Simultaneously, Shinjuku, a major transportation hub, became a rendezvous point where couples separated by great distance or lacking private spaces could find solace in exchanging intimacy. Thus, these images not only expose the hidden sexual encounters but also chronicle a rarely-seen Japan. As Martin Parr wrote in The Photobook: A History, Volume II, the series is "a brilliant piece of social documentation, capturing perfectly the loneliness, sadness, and desperation that so often accompany sexual or human relationships in a big, hard metropolis like Tokyo."

When it was first exhibited in 1979, the series sparked outrage as it captured an otherwise un-represented area of Japanese life and revealed an underbelly to the city's otherwise polished and reserved surface. In this controversial debut in a Tokyo gallery, Yoshiyuki had chosen to exhibit his pictures in darkened rooms, handing torches to visitors as they entered the space. "I wanted people to look at the bodies an inch at a time," he said. The idea was also to create a situation that could, in a way, mimic the experience of stumbling across these scenes in a park, further enhancing the feeling that the viewers are looking at something that they perhaps shouldn't.

Being part of something that is taboo is what makes the concept of voyeurism captivating to both artists and photographers. Yoshiyuki's images position the viewer as a "peeping Tom" while simultaneously questioning the motives behind the act of viewing. The works invite introspection about who was looking, why, and whether the audience should partake in this viewpoint. As Nan Goldin famously said, "There is a popular notion that the photographer is by nature a voyeur, the last one invited to the party."

Yoshiyuki revisits the themes of intimacy and voyeurism in 1978 companion project, Love Hotel, capturing grainy stills from hidden-camera footage in Tokyo's "love hotels"—exclusive venues for prostitutes and their clients. Yoshiyuki's work joins a lineage of photographers exploring voyeurism, echoing the practices of Walker Evans, who photographed subway riders in the late 1930s using decoy lenses and concealed cameras, or Weegee, who utilized infrared flash and film in movie theaters during the 1940s to capture unsuspecting viewers and amorous couples.

A body of work that only gained global acclaim decades later, The Park has left an indelible mark on visual culture. By capturing the clandestine world of Tokyo's parks, Yoshiyuki unearthed a society liberated from the constraints of daylight, evoking nocturnal nature photography. Captivating yet unsettling, these images provoke contemplation about the intricate dynamics of observation while raising questions about our attitudes towards surveillance, voyeurism, and photography within ever-evolving societal norms.