Maria Sibylla Merian, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, 1705

Maria Sibylla Merian, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, 1705 For several years, starting in 1699, an unnamed group of Surinamese people was sent into the jungle to collect insect and plant specimens for a European naturalist and entomologist. Her name was Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), and together with the younger of her daughters, Dorothea, she left the shores of Europe for South America, specifically for today's Suriname, where she planned to document the life cycles of insects and the botanical wonders of the region. Forgotten by history and deemed insignificant to be mentioned by their names even by Merian, this group of Surinamese remains among many Indigenous contributors to European science, whose knowledge and labor were exploited without acknowledgment.

The outcome of this forced alliance is a marvelous collection of New World plants, insects, and animals published in 1705 that fascinated scientists for its incredible details and accuracy, titled Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (Transformation of the Surinamese Insects). However, this achievement was soon forgotten. The fascinating book and its author only resurfaced in recent years following feminists' efforts to highlight neglected historical accounts of important women.

The latest news on the topic comes from Amsterdam, where The Rijksmuseum announced the acquisition of the first edition of Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium for its collection. "This acquisition marks the fulfilment of a long-held wish of the Rijksmuseum. Good copies of the first edition from 1705 rarely appear on the market," explains Alex Alsemgeest, curator of the Library collections.

This book's artistic quality and innovative scientific approach make for a work whose every aspect connects with the stories we want to tell at the Rijksmuseum.

However, the story of this masterpiece of art and science and its author framed as a heroic narrative of a woman's fight against the gender norms of her time and a scientific breakthrough is incomplete without the consideration of its complex colonial history, normative knowledge production, exploitation, and even kidnapping.

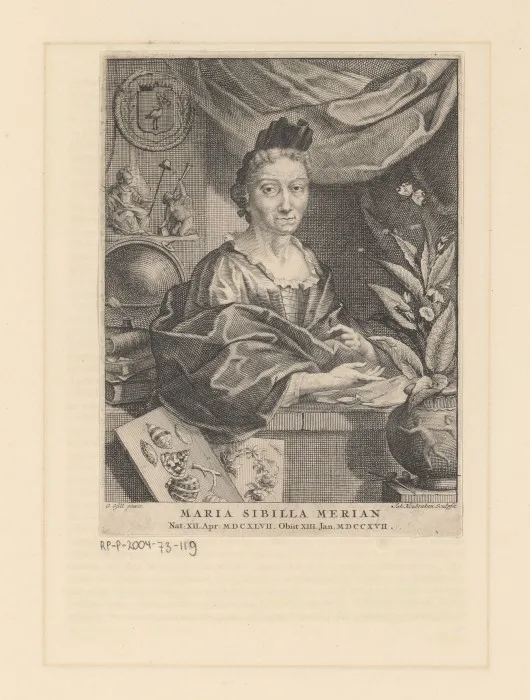

Born in Frankfurt am Main in 1647, Maria Sibylla Merian came from an artistic family. Her father, Matthäus Merian, was a famous engraver, artist, and publisher, and her stepfather, Jacob Marrel, was a painter and art dealer. She showed interest in insects from a young age and bred caterpillars herself to explore their development. Her scientific eye was complemented with her talent for drawing, and many researchers of her oeuvre praised her depictions of insects. "Merian raises the portrayal of insects to great art," wrote art historian David Friedberg in 1991.

In the 1680s, Merian moved to the Netherlands, an increasingly powerful and wealthy country thanks to its Dutch trading empire. It was also a time of colonial expansion and a strong urge among Europeans to classify and organize the known world. The idea of hierarchies and categories influenced the scientific impetus of the time, and Merian followed this trajectory. However, being a woman made it difficult to be recognized as equal among her male peers. At a time when Carl Linnaeus was hailed for his Species Plantarum—which established a binomial system for naming plants and modern plant taxonomy—Merian turned to her childhood passion, forging a niche for herself in natural history circles with her observations of insects.

Merian's trip to the Dutch colony of Suriname could be as well the first European scientific field work trip. Impressed by numerous cabinet collections filled with different wonders that arrived to Amsterdam from colonies—including numerous specimens of tropical butterflies—Merian embarked on a journey that would prove significant for a better understanding of the natural as well as social history of the time.

Seized by a Dutch fleet in 1667, Suriname remained under Dutch rule until 1975, suffering a long period of oppression and exploitation. Besides locals who were serving the Western masters, enslaved people were shipped from West Africa as well and often suffered inhuman treatment while working on plantations. The country was also attractive to Western botanists and explorers of different sorts who studied its natural resources and wildlife.

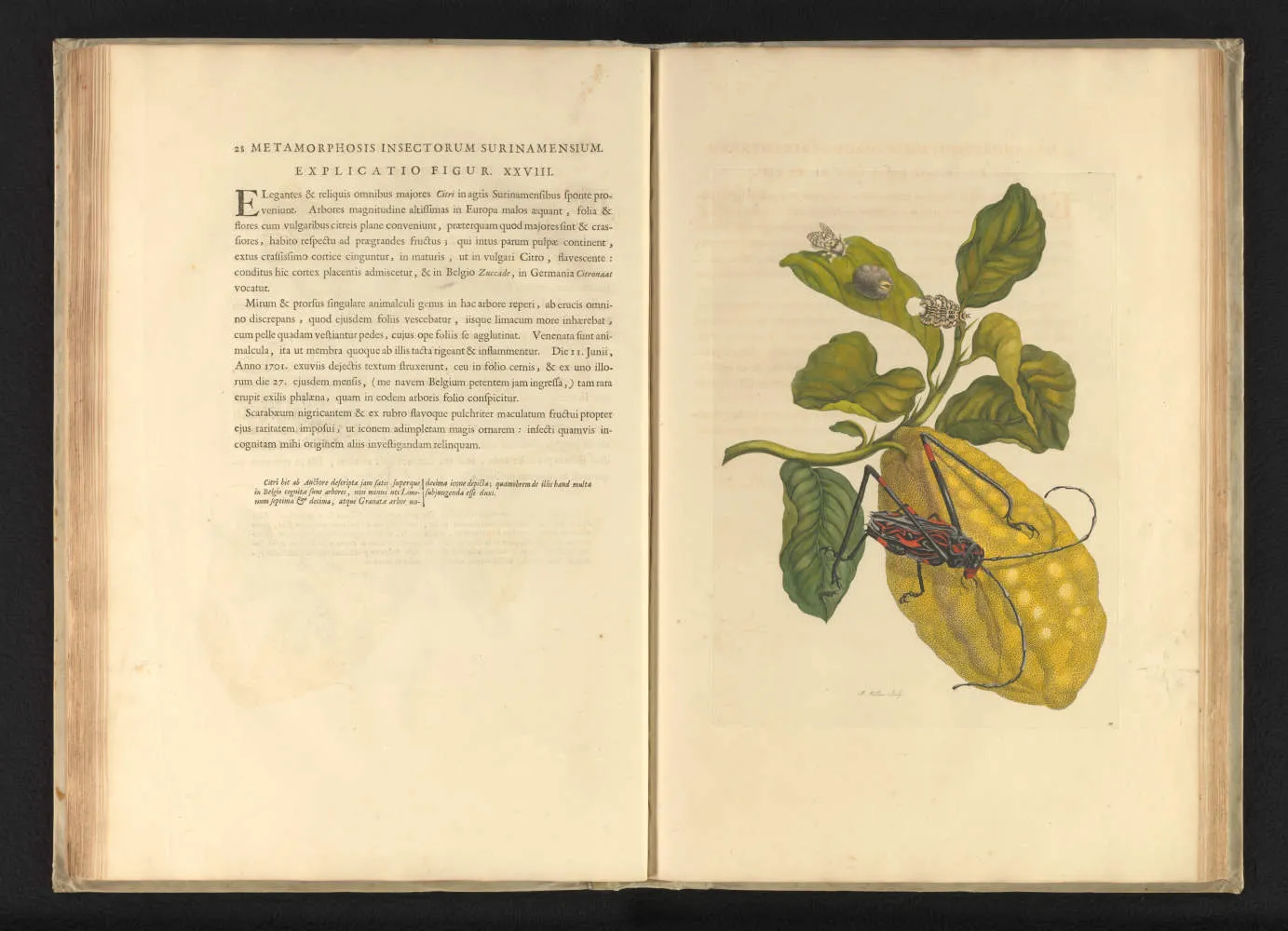

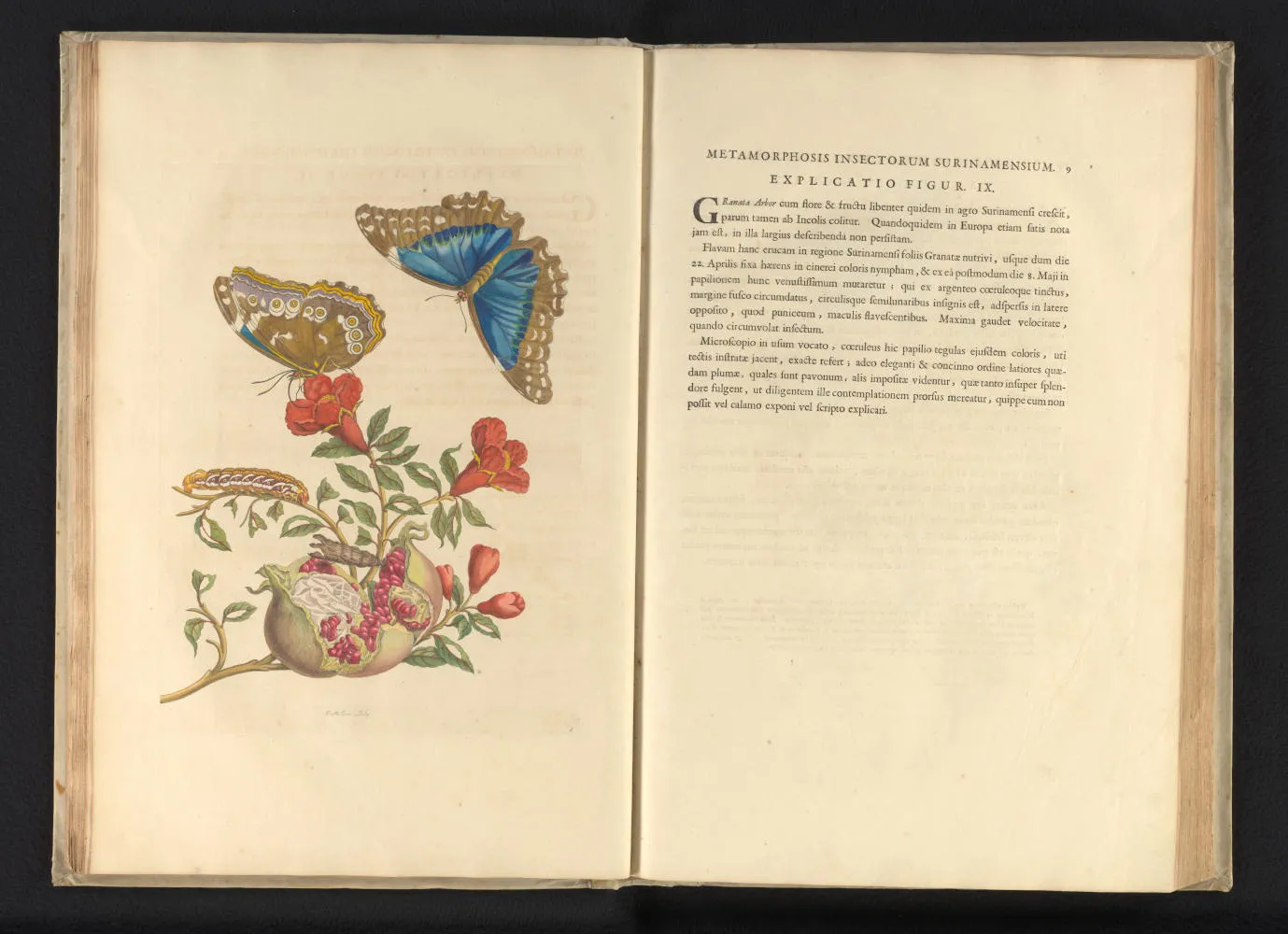

Merian and her daughter spent two years in Surinamese rain forest before returning home in 1701, where she completed the volume, including her decadent depictions of tropical plants, moths, and butterflies. Each plate was accompanied by Merian's account of her life and animals, "all of which I myself sketched and observed from life, with the exception of a few which I added on the testimony of the Indians."

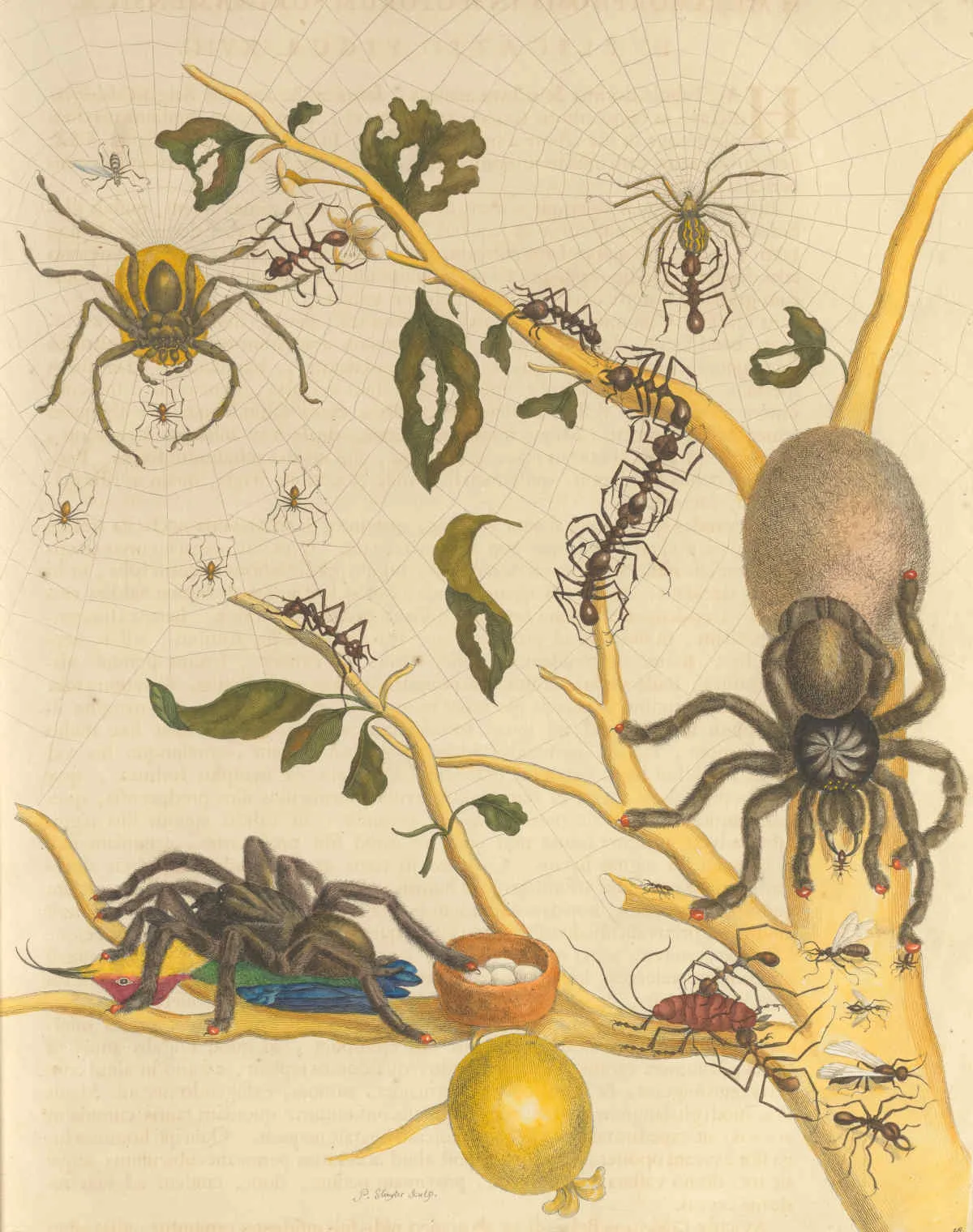

Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium was first published in Amsterdam in 1705 and contained 60 hand-colored plates featuring caterpillars, spiders, and butterflies depicted in radiant colours and rich hues. The book features the phases of their development and is interspersed with Merian's notes, including those on the Dutch colonial practices and enslaved people.

The famous description of the peacock flower included the following passage as well: "The Indians, who are not treated well by their Dutch masters, use the seeds to abort their children, so that they will not become slaves like themselves. The black slaves from Guinea and Angola have demanded to be well treated, threatening to refuse to have children. In fact, they sometimes take their own lives because they are treated so badly and because they believe they will be born again, free and living in their own land. They told me this themselves."

A particularly striking detail is her acknowledgment of the injustices the colonial system brought, as well as descriptions of medicine that women used for abortion. In this regard, "she was ahead of her time," explained biologist Key Etheridge for NYT. Merian believed that European colonists would help her get around and support her research, but when this failed, she turned to indigenous people as a source and guidance. Therefore, her book is not only filled with careful observation of insects but also of customs of the locals that helped her. Although she did not record their names, Merian recognizing their contributions and included passages that mentioned enslaved people and servants who assisted her and whom she sent into the jungle to collect plants and insects for her.

The luscious images in Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium were printed recto verso, meaning that the colour drawings were visible on the back of the paper. This detail caught the attention of the artist Patricia Kaersenhout, to her new series of drawings titled Of Palimpsests & Erasure series of drawings that highlight the context of Merian's book and the invisible work that went into it. Focusing on Surinamese women who helped Merian with the collection and depicting them opposite Merian’s illustrations, the artist addressed the fraught history of European natural science and the processes of exploitation it usually entailed.

While her contributions were significant—from discovering facts about plants and insects to collecting knowledge about natural remedies and medicine (with occasional errors)—Merian should not be observed outside the 18th-century global political economy. Natural history was the dominant science of the period, and while her work was primarily dedicated to observing the life cycles of butterflies and moths, she also contributed to the colonists' search for profitable plants and insects, the so-called 'biogold,' that would bring profit to Europeans. Quinine, when discovered by the Spanish in Peru, brought them millions, and Merian believed that she could find a caterpillar that would rival silkworms in the quality of thread.

Relying on local knowledge was so important to Merian that she even went as far as to kidnap one Surinamese woman called Mijn Indiaan and take her back to Amsterdam with her. Her destiny after arriving in Europe is unknown. Although Merian inspired other botanists, notably George Shaw, who named a tree frog after her, her work was forgotten in later decades, especially when Victorian morality pushed women back into households more firmly. However, her portrait, made by the Dutch engraver Jacob Houbraken in the style of portraits of leading scientists where her contribution to entomology is clearly highlighted, testifies to her importance and appreciation at the time.

Although recognized as a pioneering naturalist, Merian’s image remains incomplete without other women who helped her in her endeavor. In the vague drawings on the back of her illustrations, Kaersenhout recognized "a metaphor for the black women and women of color who have been 'dissolved' in history..." While Meiran received reappraisal in recent decades, these women's names remain lost to history. "The bodies of the women 'disrupt,' as it were, a dominant history and thereby at the same time claim a place in a history that has actively wiped them out or erased. When the viewer views the works from a one-sided hierarchical perspective, the work will not unfold..." Kaersenhout explains.

Only a full comprehension of the historical moment and the layers that surround the book and Merian's work will allow for this unfolding. Only through art, it seems, the full knowledge finally materializes.