Mirna Bamieh, 2024. Photo by Patrícia Soares, CRUAMEDIA

Mirna Bamieh, 2024. Photo by Patrícia Soares, CRUAMEDIA For Palestinian artist Mirna Bamieh, the kitchen serves as a powerful starting point for storytelling, reflection, and resistance. More than just a domestic space, it becomes a living archive where memory, resilience, and identity are sustained through everyday rituals. Bamieh’s work is deeply rooted in the act of cooking and sharing meals, transforming these practices into political acts that assert cultural identity in the face of oppression, carrying with them histories of displacement, survival, and belonging.

Bamieh's work transcends traditional artistic forms, inviting audiences to explore the political, social, and cultural narratives that shape Palestinian collective identity and memory. In 2017, she founded the Palestinian Hosting Society, a live art project that revives and reimagines Palestinian food practices and recipes, preserving them from disappearance. Through this initiative, meals become moments of exchange, where layers of history, identity, and memory are brought to life. By intertwining these narratives with the act of eating, Bamieh creates spaces for cultural resistance, engaging participants with stories that might otherwise fade.

Her ongoing series Sour Things, first debuted at the Sharjah Biennial in 2023, explores the intersection of traditional methods of fermentation and preservation with personal and collective histories, particularly within the context of Palestinian identity. Bamieh transforms food preservation into a narrative vessel, emphasizing its role in safeguarding cultural heritage amidst displacement and loss. The latest iteration of Sour Things—featuring new installations The Pantry, The Staircase, and The Wall—inaugurated NIKA Project Space Paris this fall, while the expansion of Sour Things: The Kitchen, which first debuted at NIKA Project Space Dubai last year, marked Bamieh's largest solo exhibition to date at ICA Shanghai. On the other hand, her installation Bitter Things is part of the current group show Ecologies of Peace II, on view at Centro De Creaction de Andalucia in Cordoba until March 30th, 2025.

Sour Things examines fermentation as a site of collective memory, autonomous archiving, and historical writing, presenting models of domesticity shaped by the tragedies unfolding in Gaza and the West Bank that have displaced Bamieh. These installations transform familiar spaces into profound reflections on dispossession and survival, inviting viewers to consider the embodied experiences of the displaced. She questions whether and how preservation is possible in a state of liminality, as she navigates the fractures of uprooting and the challenge of holding onto tradition.

In this conversation, Bamieh delves into the intersection of food, memory, and identity, shedding light on how Palestinian food culture has been shaped by political oppression, displacement, and fragmentation. Reflecting on the personal and communal significance of food, she emphasizes how cooking and sharing meals have always served as acts of defiance, connection, and cultural preservation. Bamieh also discusses her projects, such as the Palestinian Hosting Society, Sour Things, and Bitter Things, and how through her lens, decay becomes a site of potential, and preservation emerges as a powerful act of healing and resistance.

Jelena Martinovic: Your work primarily explores themes of memory, identity, and the politics of food. What early experiences shaped your relationship with food, and how do they continue to inform your artistic practice?

Mirna Bamieh: Food was a central thread in my upbringing. My mother, who married young, learned to cook as she adjusted to her new life in Palestine, away from her family in Lebanon. Her kitchen became a bridge, a way to stay connected to her roots. I remember her spending hours on the phone with my grandmother, learning recipes and reconstructing a sense of home through food. For her, cooking was not just about nourishment but also about identity—a dialogue between Palestine and Lebanon, between belonging and longing.

The kitchen table, therefore, was more than just a physical space; it became a site of experimentation, exploration, and conversation. This deeply personal relationship with food—its power to create connection, hold memory, and negotiate identity—continues to shape my artistic practice.

My serious engagement with food as an artistic medium began in 2016, during an art residency in Tokyo. It was a time of global uncertainty, especially for the Arab youth. The disillusionment that followed the Arab Spring prompted me to pause and question the role of art in moments of despair. What could art offer in a world on the brink? I sought refuge in food—a subject as layered and complex as any medium I had worked with before. Through food, I found a lens to explore history, culture, and identity, and a way to reconnect with what felt vital and human.

JM: Could you share your insights on food culture in Palestine and how it reflects the social and political realities?

MB: Palestinian food culture is a testament to resilience and continuity despite profound disruptions. Due to the political realities of occupation and displacement, much of our culinary heritage has been fragmented. Restrictions on movement, uprooting, and land confiscation have severed many communities from the foraging, farming, and cooking practices that once defined our cuisine.

I feel there's a lot of power and potential for change that can come from sharing food and making food together. In Palestinian food practices, cooking is always a communal activity. It's never about one person alone in the kitchen cooking while another just receives a plate and eats. It's always tied to family and community. Traditionally, it's the extended families working together in the kitchen. Palestinian cuisine is also deeply attuned to the seasons, the climate, and the agricultural calendar, linked to harvests and festivals. Cooking has always been a social action, and fortunately, we haven't lost all of that—but we have lost a lot.

Movement, for example, is not as accessible as it used to be decades ago. The map is literally disappearing, fragmented into isolated islands that we cannot easily access. People in Ramallah can't easily go to Jerusalem without a special permit. People in Jerusalem and the south can't go to Gaza. Gazans can't leave Gaza. Freedom of movement always involves negotiation, requiring proof that you can leave where you are, which is deeply violent. Oppression dictates daily life, determining what people can and cannot do. This disruption breaks the flow of knowledge, including kitchen knowledge.

Palestine is a small country with a very rich landscape. The north has a specific cuisine tied to its unique crops and climate, which are completely different from those in the south, where the environment brushes against the desert. Gaza, with its Mediterranean coast, has yet another distinct culinary tradition. Palestine has three seas and a mountain with snow, so these are entirely different climates. Some communities are secluded and are not exposed to the sea at all. The practices of preservation are very important and are the core of the cuisine, but these practices vary across the land. For instance, in Hebron, where intense heat limits access to fresh crops and hinders outdoor activities, preservation plays a crucial role.

So, we are talking about a very rich geography, but this diversity is cut off by political oppression, making it hard to access the full richness of Palestinian identity, and this is reflected in the cuisine. People in Gaza do not know what people in Galilee eat, and people in Ramallah do not know what the Gaza eat. For me, that is part of the disappearance. There are a lot of traditional dishes that we don't know as Palestinians because traditional recipes are also falling out of memory because it's hard to access the memory holders due to these political realities.

What makes this even more challenging is the systematic appropriation of Palestinian food and its rebranding as something else—a form of cultural erasure that mirrors the broader political struggle. Food, in this context, is not just sustenance; it is a battleground for identity, memory, and survival.

JM: There are also bans on collecting wild plants?

MB: Yes, exactly. And that really reflects on seasonal crops like akkoub, which is gondelia in English. It's a thorny plant that's very seasonal at the end of spring. People in Nablus love it so much; during the season, it's all over the mountains and markets. But now it's farmed, because the wild one is prohibited from being foraged. That affects the taste, but also, the ritual of going to the mountains, collecting the gondelia, going back home, and cutting the thorns is missing. This is how you practice your identity—by walking in the landscape, offering something to nature, and investing your time. That's what makes the dish you present to your family special. It's part of practicing your Palestinian identity.

You know, it's not just food; it enhances who you are and builds memories. Without that, when you present this dish—though akkoub is still available in its farmed form—every time you cook and eat it, you reflect on how the taste is missing. And that missing taste feels more profound because you, as a Palestinian, are missing an experience that has been prohibited by Israel, by political oppression, by injustice. So, this dish becomes different; it becomes a space of mourning, not a celebration.

We need to recognize that even these bans are intentional. For example, akkoub was prohibited after it was recognized how vital these plants are to the Palestinian psyche, contributing to a sense of richness, pride, and identity, as well as shaping how Palestinians perceive themselves. On another level, there's also an economic factor. When you prohibit locals from getting food for free, they'll find ways to get it, and with that, money can be made. Palestinians cannot stop eating, but they can be forced to buy.

For instance, the ban on za'atar started in 1976, I believe, and at the same time, there was a significant effort to start planting it. So you close access to the wild, but you open a market for farming and selling. This happened with all three crops. It’s not about making them inaccessible; it's about disrupting the ritual of how Palestinians access them. It makes it unsafe to go to the mountains to forage, but at the same time, it forces Palestinians to buy what used to be freely available.

JM: You founded the Palestine Hosting Society in 2017. How did this project come to be, and what inspired its focus on reviving disappearing Palestinian recipes?

MB: The Palestine Hosting Society emerged from my growing realization that a significant part of Palestinian culinary knowledge is at risk of being lost. This loss is tied to the political fragmentation and uprooting of our people, compounded by restrictions on documenting, foraging, and practicing traditional foodways.

I brought my background in the humanities into the kitchen, using it to study, archive, and reactivate these recipes. Culinary school gave me the technical vocabulary of the kitchen, and from there, the Palestine Hosting Society took shape. The project is a living archive, brought to life through dinner performances, talks, and walks—both in Palestine and beyond.

In 2020, my focus deepened into fermentation and preservation practices. The pandemic brought a heightened awareness of scarcity and survival, and I found solace in fermentation. This ancient process became a metaphor for resilience, transformation, and care—a way to reflect on both our shared vulnerabilities and our capacity to endure.

JM: The project brings the dishes on the verge of disappearing back to life through dinner tables, talks, walks, and various interventions. Could you walk us through your working process for these dinner performances?

MB: For me, when I started Palestine Hosting Society in 2017, it came from a need to create a project that could be a learning space for me as a Palestinian who has always appreciated the power of food. I realized there's so much richness in the traditional Palestinian cuisine that I didn't know anything about. My interest in food was always there, but thinking of food as a research topic and a medium came when I realized I needed to create projects that involved people, because that's what I missed in my life and where I saw value in my practice.

Food was a starting point because it's embedded—I really appreciate its power. When I wanted it to become a part of my life, I went to culinary school in 2016. That's when I realized what we were taught there had nothing to do with Palestinian cuisine. The Palestinian cuisine was just one class in the curriculum, even though I was studying in Palestine. When I tried to access information about it, I found that most of it was inaccessible to me. My parents didn't know much about it, and the older generation thought my generation wasn't interested, so they didn't pass it down easily.

There are also many reasons why traditional cuisines are falling out of practice, and some of these reasons are by design. Traditional dishes require more people to prepare them. Food is less accessible now, and people choose easier recipes. Foraging plants isn't as common as before, so certain dishes stop being cooked.

I started my research simply by going to the older generation and asking about the dishes they used to eat as kids but no longer eat. I would visit certain villages and cities and spend months there, trying to understand the history of the place—what they used to plant, what they stopped planting, the different communities that inhabited the area, and how they shaped its cuisine. For example, I went to Nablus, a city in the West Bank, and spent months speaking with people. I learned about the history, the cuisine, and how it differs from the cuisine in Jerusalem.

Being Palestinian helped me, of course, because I speak the language and have a deeper understanding of the place. People opened up when they realized someone was interested in the knowledge they had—knowledge that was becoming devalued and seen as not worth passing down. That started a rich journey for me, getting to know people, their stories, their family histories, and connecting the dots. It felt like an investigation, which I loved.

After focusing on specific topics, like the cuisine of Nablus, the cuisine of Jerusalem, wild plants, or wheat, I would hold a dinner performance. During the performance, I shared the knowledge I had gathered, acting as a performer. I told the stories of the dishes people were eating. It was like a theatrical experience, choreographed with sounds and music that were commissioned and related to the food being served.

Other outcomes of this research included walks, like the ones I did in the Old City of Jerusalem, and talks like the Tahini Talks, which focused on the history of tahini, the disappearance of red tahini, and how these connect to politics, time, and people.

JM: Potato Talks were also part of the project?

MB: Potato Talks marked the beginning of the Palestine Hosting Society. I realized how much could be achieved with food—how it brings people together and creates space for conversation. At Potato Talks, the focus is simply the potato.

The reason I started working with food is that I missed the human aspect in my work. As a video installation artist, by training and practice, combined with a nomadic life traveling for over a decade, my work became solitary. I worked mainly with my body, my story, and my face, and I wanted something beyond that. I wanted my practice to feel less lonely. The first edition of Potato Talks was in 2016 in Marrakesh, followed by editions in Ramallah, Jerusalem, Italy, and I will perform it in Zürich in March.

Each edition has a theme, and I work with a group of 8–12 people to develop it. The participants become storytellers—potato storytellers. We work together to connect the theme to a personal story and the potato. Once the stories are ready, they perform them.

The performances always take place in public spaces, usually in squares. Each storyteller sits on a stool with an empty stool next to them and a pile of potatoes nearby. The layout forms a cluster with pairs of stools—one for the storyteller and one for the audience member who joins. Passersby are invited to sit in the empty stool, and the storyteller gestures for them to help peel a potato. While peeling, the storyteller maintains deep eye contact and shares their story. It's an intimate, unexpected encounter, almost like a gift that falls into someone's lap. After two hours of storytelling, the peeled potatoes are cooked and shared with the people in the square, turning the performance into a collective social event.

Next year, I hope to take Potato Talks to Lisbon. I know it will happen. The project gives me energy, especially after last year when I delved too deeply into Sour Things. I was processing a lot of sourness from the world around me, and now I need balance—returning to people.

I still find ways to connect with my roots. Although I left Palestine abruptly, I continue to search for za'atar and olive oil that remind me of home. These connections are essential to my work and life.

JM: Storytelling plays a central role in your dinner performances. How do narrative and food interact in these experiences?

MB: It's all about storytelling—the performance is entirely about storytelling. I see myself as a collector of stories, not just recipes. When I tell people the stories of these dishes and how they have disappeared, I also share the stories of those who taught me these dishes. Sometimes, those same people even come to the performances and speak. Each dish carries layers of history, memory, and identity, and the act of sharing these stories over a meal creates a collective experience. The table becomes a site of resistance—a way to reclaim and preserve what might otherwise be lost.

The power of food isn't just in its nutrients or how delicious and wholesome our food and cuisine are, but in the richness of the stories behind the dishes. For me, that's where the value lies, and that’s why I want to revive these stories. They are not just individual narratives; they are stories we need to reintroduce into our collective Palestinian body. Moreover, these stories should sprout and inspire new ones that we can pass on to the next generation.

These performances create a living archive—one that generates ongoing knowledge. When people eat the dish and hear its story during the performance, it becomes part of their lives. They might talk about it, feel more curious, or even dig deeper into their own family histories. This is why I love doing these performances in Palestine: they encourage people to reconnect with the richness and importance of their own family history and heritage.

By reviving and sharing these recipes, I'm not only preserving culinary practices but also reanimating the histories they hold. This intersection of narrative and food creates a bridge between the personal and the collective, the past and the present.

I truly believe one of the powers of art lies in its ability to generate stories. As a nation that has been colonized and occupied for so long, our voices and stories are crucial as acts of resistance against the oppressor's attempts to erase our identity.

The colonizer, the oppressor, the occupier—they want us to forget our power and strength, to give up and surrender. But when we embrace this pride, this richness, and this knowledge of who we are, it becomes harder for them to erase us or make us disappear. Gathering and telling stories is a powerful space for enhancing and strengthening collective identity. And there's nothing more meaningful than having this mediated through food. When we talk about food, we're also talking about landscape, farming, people, and history.

JM: The politics of disappearance and memory are central in your work. How do you see the act of cooking and sharing meals functioning as both a personal and collective form of resistance against the efforts of erasure?

MB: Cooking and sharing food have always been integral to the resistance movement in Palestine. The kitchen is not just a place for preparing meals—it's a space for gathering, recruiting, and planning. It's about sustenance not only in the physical sense but also in terms of morale, creating community, and envisioning the future. There are countless stories about food during the First Intifada and other periods of resistance.

Even now, if we look at Gaza, food holds profound significance. It becomes a source of hope amid immense hardship, but it's also weaponized against people—making them hungry, restricting access to resources, and driving up costs to unbearable levels. In these moments, survival itself becomes an act of resistance.

Yet, you see people coming together to bake, tapping into indigenous knowledge of how to make food with the bare minimum. They learn to forage wild plants, use alternative grains to make bread, or craft their own tools, like clay ovens, when there’s no electricity. Recipes are reimagined to work with fewer ingredients, adapting to the circumstances

The heartbreaking genocide in Gaza highlights this resilience. Food becomes more than sustenance—it's a way to build community, foster survival, and resist efforts to erase identity and memory.

JM: Your Sour Things series explores themes of grief, displacement, and memory. How did fermentation become both a metaphor and a method in this body of work?

MB: Fermentation sits at the threshold of decay and preservation, life and death. It's a transformative process that mirrors the complexities of displacement, grief, and survival. Through fermentation, I began to explore how time, care, and microbial ecosystems could serve as metaphors for resilience and connection.

Fermented foods embody paradoxes—they decay to preserve, they sour to heal. These processes reflect broader ideas about how communities survive and adapt in the face of loss. The bubbling of ferments became a powerful symbol for me, evoking ecosystems of care and transformation, even in challenging conditions.

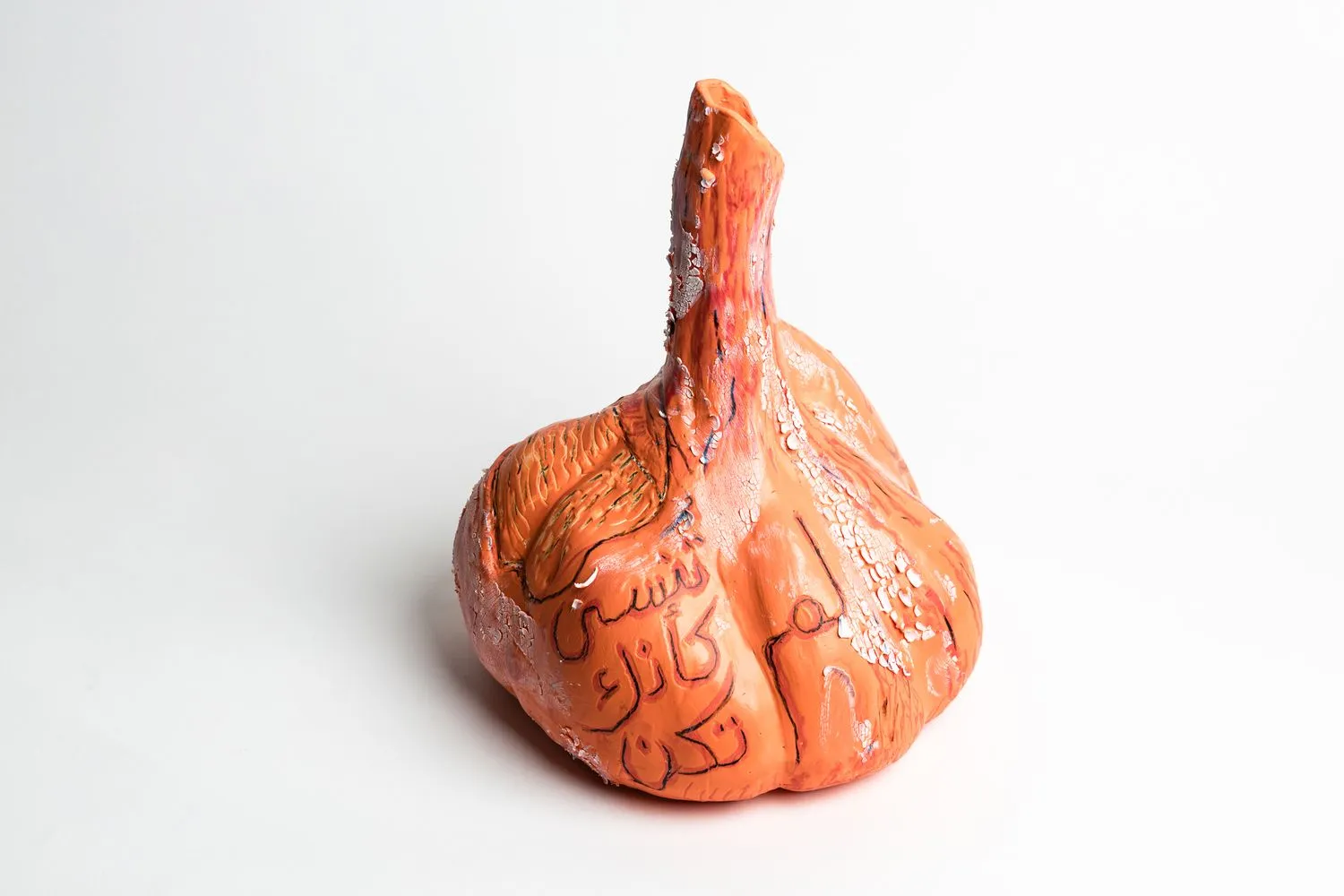

Sour Things is still an ongoing project. We've had two iterations of The Kitchen, and together, Sour Things is a single apartment. It includes the kitchen, the pantry, the hanging pieces, and the show. The Sour Chords are part of Sour Things, as is The Staircase. The Grieving series is also part of Sour Things, specifically The Wall. This year, I'm working on Sour Things: The Door, Sour Things: The Bed, and hopefully Sour Things: The Table and The Washroom. Together, they form one apartment.

For The Door, I'm focusing more on the immigration experience and the food that people pack from their homeland to bring to their new places of residence. It’s about this connection through food that people create with the places they come from. These foods are like memory capsules. They’re not just olive oil or whatever; it's the symbolic bond with the homeland that people don't want to sever. They want to ensure that the connection becomes part of their life in the new country and part of their family's life in that new place.

JM: The notion of a pantry, both as a space of sustenance and anticipation of scarcity, is key in your recent work. How does this speak to the Palestinian experience of displacement, uprooting, and the loss of space?

MB: In The Pantry installation, I was looking at uprooting—how the pantry of an uprooted person looks when you have no control over access. It's not just about control over a place, but about losing access to the space that defines the pantry itself, which is often part of a house. When you're forced to leave your home and can't access your pantry, the act of preservation shifts: your body becomes the space you need to preserve in order to survive.

I view the pantry in this context as the "guts" of the uprooted—the gut of the immigrant, the gut of the displaced. It’s a space that exists and doesn't exist at the same time. This idea came from a personal experience. I was in Palestine when the war started. I had just returned after being away for eight months, arriving at the beginning of October. When the war began, I had to leave at the end of October. Unlike previous trips, I wasn't sure when or if I would be able to return.

This time, I had to empty all my jars, clean my kitchen, and discard my kombucha culture, which I had nurtured for five years. It was like bidding farewell to my pantry, my kitchen, and my house without knowing when I might return. Although it doesn't compare to the destruction happening in Gaza, where houses are demolished over people’s heads, it was still a violent and deeply political experience for me. I wouldn't have chosen to leave if it weren't for the war. Not knowing where I would end up or what the future held added to the anxiety.

In The Pantry installation, the emptiness of the jars reflects this anxiety. The pantry is filled instead with objects, drawings, and videos created during the war. These include drawings I worked on when I first arrived, as well as videos made during my last week in Palestine. The process was intense—I worked 15-hour days from December to mid-January, trying to process the trauma I was experiencing, a trauma tied to the collective body of the Palestinian people. It was too hard to contain.

The practice of preservation carries an inherent anxiety about the future—whether you’ll be able to stay in your home, whether your land will yield a crop. But it also offers a sense of control in the moment. When you have access to produce, you preserve it to ensure survival: drying tomatoes, pickling, fermenting yogurt, or making cheese and jameed. You dry okra, chili, garlic, and onion, string them into necklaces, and fill jars with olive oil. These are all practices of preservation we've developed to prepare for times of scarcity.

War intensifies this anxiety, especially when you can no longer preserve food because you've lost your home. It becomes even more violent. The question then becomes: how do you preserve your body when it is under attack? How do you ensure survival and create self-preservation so that you can reach a future?

JM: In your current exhibition in ICA Shanghai, you have created a space where the body intersects with the structure and contents of the kitchen. Could you tell me more about this relationship between the body and the kitchen?

MB: The body is a significant theme in my work. Much of what I create reflects on the body—my own, the human body, and non-human bodies, like bacteria cultures, in relation to mine. I explore what we, as humans, can learn from non-humans, such as bacteria, which are so much stronger in many ways.

In The Kitchen, specifically in Sour Things, I deal with themes of access, ingestion, digestion, and overflow. The Kitchen installation in Shanghai is the same structure as the one first shown at NIKA Project Space in November 2023, which was the first piece I presented after leaving Palestine. It was designed as a kitchen for one person, reflecting on the idea of forced consumption—not only of food but also of media, news, and things we are compelled to take in against our will.

There's also an anxiety that arises from how people engage with the piece. The space is heavy—there's the sound, the videos, and the structure itself, which is open and L-shaped, but it really engulfs you. I always think about the viewer's body in relation to movement when creating installations like Sour Things. Part of that experience includes the pantry, where the objects are placed, and viewers often have to kneel or get closer to see them. The sound adds another layer of physical experience, entering both the body and the mind. The text I've written also induces anxiety.

The Shanghai iteration retains the same structure but features fewer, larger objects. For instance, in Dubai, there were 40 small ceramic fingers; in Shanghai, there are just two, but each is 40 centimeters long, making them grotesque and impossible to ignore. This change emphasizes presence and visibility—the objects are louder and more visceral, shifting the work into a statement rather than just an installation. Similarly, what were once small hands are now oversized, nearly 50 centimeters, resembling bodies themselves. These changes transform the installation into a statement.

JM: This exhibition also features recipes and texts that combine poetic observations with personal histories?

MB: As you know, it's a solo show, and actually my biggest one. It's quite large, with The Kitchen as the centerpiece, but there are other components as well because it's also in NYU Shanghai. There's an interactive aspect to how things were made. For example, there was a reading table with texts I created for Sour Things, which includes recipes. Writing always precedes making things for me. My work with fermentation started in 2019, and that was the trigger. It started in Warsaw, and I began writing without knowing where it came from, but it came strongly, like a gush. I realized that there were things I could express through writing—feelings I could induce—that I couldn’t do with other mediums I work in. Writing has always been the blueprint for everything I do with Sour Things.

For this exhibition, 11 texts were accessible for people to read. We did something similar in Sharjah in 2023 at the Sharjah Biennial. There was a long waiting table with objects, and then there were the shops. We repeated this in Shanghai, where people could sit and read and see the recipes connected to the pieces.

JM: How do Bitter Things, currently on view at TBA21 in Spain, differ from Sour Things?

MB: Bitter Things is another kitchen project, distinct from Sour Things. It is inspired by the bitter orange—a citrus abundant yet underutilized. Unfortunately, as we are losing the knowledge of how to process this bitter citrus, it is often planted as urban decorations, facing neglect and disconnection from traditional knowledge. This disconnection from traditional knowledge is a growing issue, particularly in Andalusia, where these trees have become part of urban planning.

For an exhibition with TBA21, I worked with trees from the museum’s grounds, harvesting 200 kilos of bitter oranges. Without this project, the fruit would have been discarded—a fate common across regions. The harvested oranges became central to the installation, highlighting this neglected resource. We documented the process, juxtaposing Palestinian and Andalusian marmalade recipes in text and video.

In Palestine, the bitter orange has long been part of culinary traditions, with recipes for concentrated juice and marmalade. In Lebanon, there are even dishes made specifically when the citrus ripens. Yet, much of the fruit remains unused, leading people to cut down the trees in favor of planting apples or sweet oranges. As a result, the bitter orange is disappearing from the landscape.

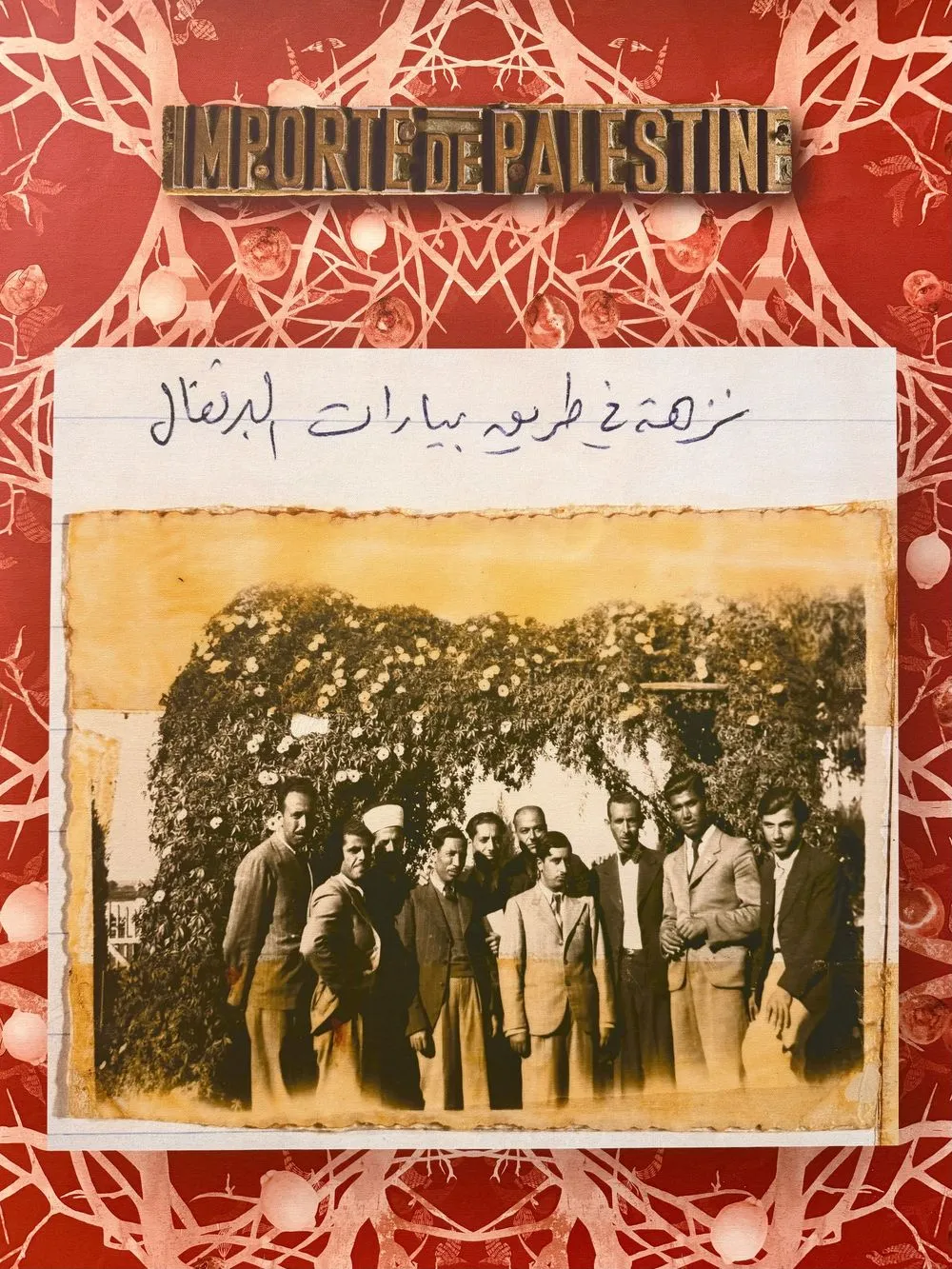

The other breed of orange I was working with was the Jaffa orange. The Jaffa orange holds personal significance for me—my paternal family hails from Jaffa. The project explores its disappearance and the intertwined histories of politics and displacement. In addition to ceramic pieces and videos, I also displayed archival prints related to Jaffa oranges. One was a memoir by a family member recounting her experiences in Jaffa, excerpted from the first book in Arabic written by Palestinians from Jaffa about the city. This archival documentation provides a vital link to the cultural and historical identity of the region.

JM: In Sour Things, there's a recurring relationship between decay and preservation. How do these concepts resonate with both personal and collective narratives?

MB: The interplay between decay and preservation is central to the Palestinian experience, both personally and collectively. These concepts are not simply opposites but rather interdependent forces that shape identity and memory. Decay, in the context of Palestine, often signifies the erasure of physical and cultural landscapes—whether through the destruction of villages, the fragmentation of communities, or the deterioration of cultural practices under occupation. However, decay does not only represent loss; it also exposes the mechanisms of power that seek to overwrite history and identity.

Preservation, then, becomes an act of resistance. It is not a passive process of safeguarding what remains, but an active re-inscription of meaning. It involves memory work, storytelling, and the reclamation of spaces and symbols. This dynamic is evident in practices like the replanting of uprooted olive trees, the archiving of oral histories, and the reinterpretation of traditional crafts in contemporary contexts.

In Sour Things, I am drawn to how decay and preservation function not only as material realities but also as metaphors for survival and resistance. The sourness of preservation—the act of fermentation, for instance—becomes a way to confront decay, to transform it into something that endures. This process mirrors how Palestinians navigate the tension between loss and continuity, finding ways to preserve not only physical artifacts but also the intangible: dignity, identity, and the will to endure.

I see this relationship through the lens of cultural and political resistance. Decay may be seen as part of a colonial strategy, a deliberate dismantling of connection and continuity. Preservation, then, becomes a decolonial act, a refusal to submit to the finality of loss. It is about asserting presence in the face of erasure, transforming the inevitable processes of decay into a testament of resilience and reimagined possibilities.

JM: In Sour Cords, the suspended ceramic food objects reference traditional preservation methods. How do these works connect to themes of healing and resilience?

MB: The ceramics in Sour Cords were inspired by sun-drying, an ancient preservation practice. The removal of water—life's essential element—paradoxically ensures the food's survival, only to be rehydrated when needed. This cycle mirrors the resilience of displaced communities, who hold their traditions in suspended states, waiting for the moment when they can bring them back to life.

In creating these objects, I found a personal metaphor for healing. They remind me of an idea I wrote for To Jar, a film I made in 2020:

"When the world was flipped upside down, those jars were my anchor, an enduring presence. While I was confined between walls, those jars opened a boundless space before me, speaking unlike ever before, of when to hold our breath inside us and change, and when to open up and breathe."

This balance between holding and releasing, between endurance and transformation, lies at the heart of my practice. The pantry becomes a space of survival and possibility, where food—and art—becomes a vessel for resilience.