© Neal Slavin, The Star Trek Convention, Star Trek Associates, A Division of Tellurian Enterprises, Inc., Brooklyn, New York, 1972-75

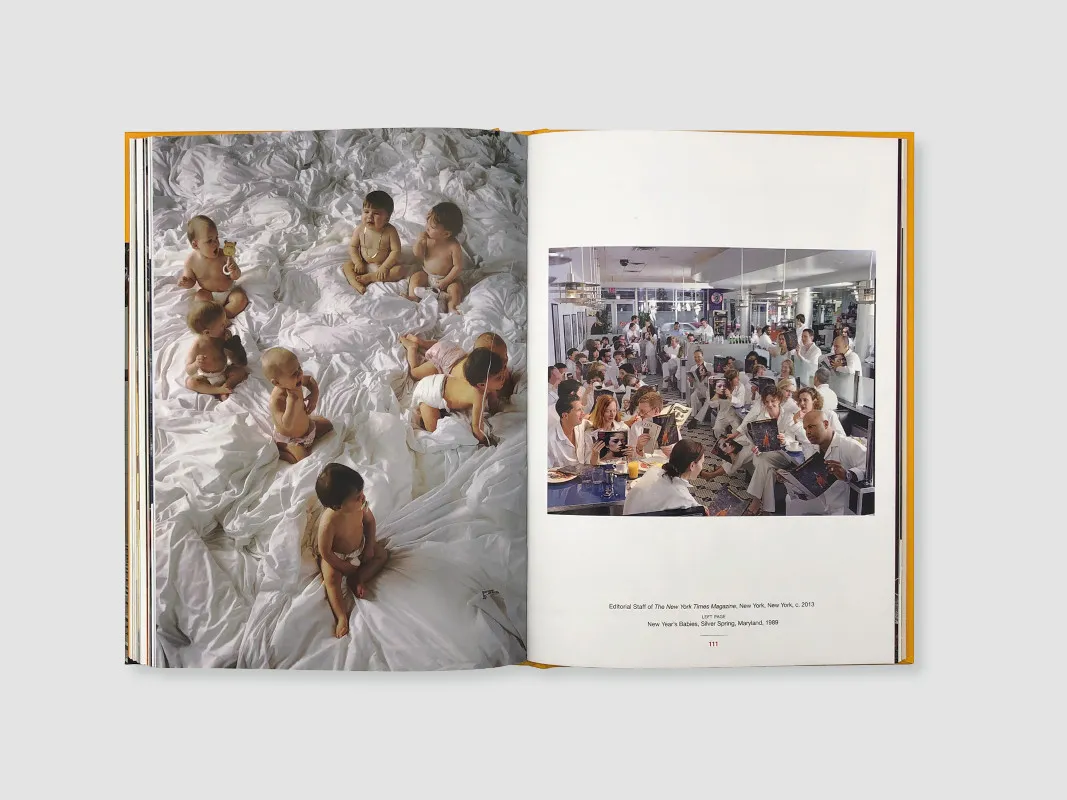

© Neal Slavin, The Star Trek Convention, Star Trek Associates, A Division of Tellurian Enterprises, Inc., Brooklyn, New York, 1972-75 Neal Slavin, renowned for his captivating group portraits, has spent over five decades documenting the essence of human connection. His work masterfully explores the dynamics of collective identity while highlighting each individual’s place within the group. What distinguishes Slavin is his ability to convey the complexity of togetherness, capturing the spirit of belonging, camaraderie, and interaction within diverse communities. The new expanded edition of his iconic book, When Two or More Are Gathered Together, revisits these collective moments, where individual identities and communal bonds intersect.

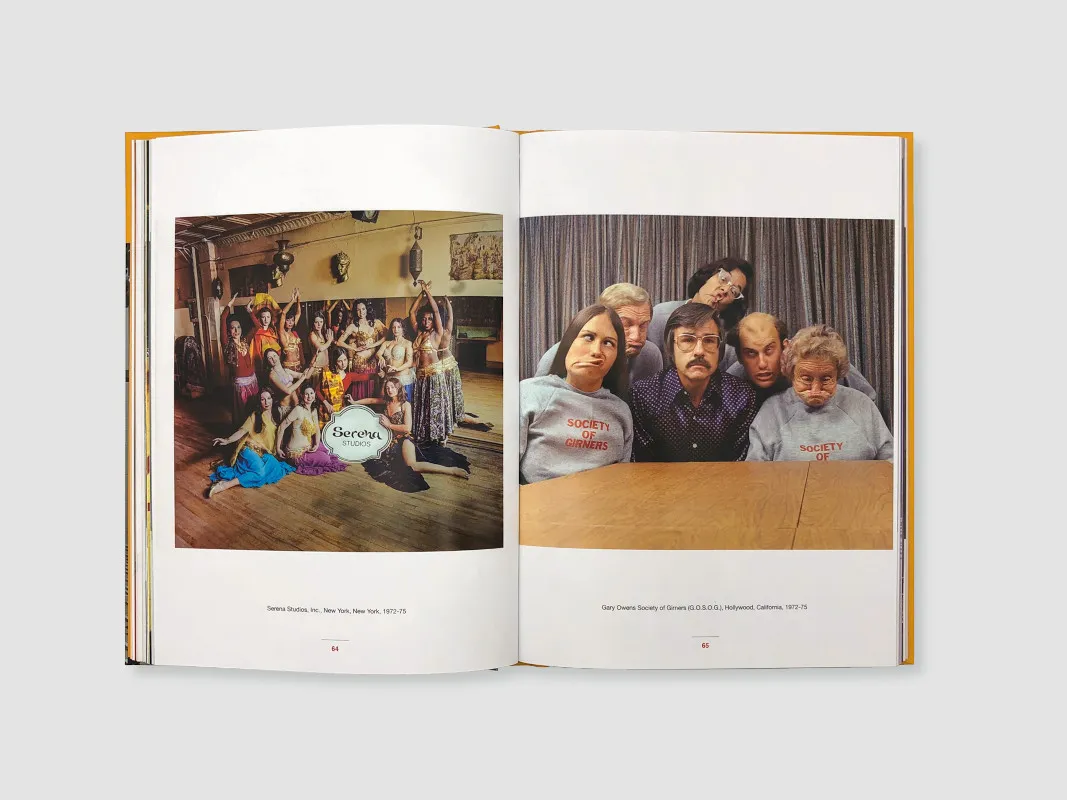

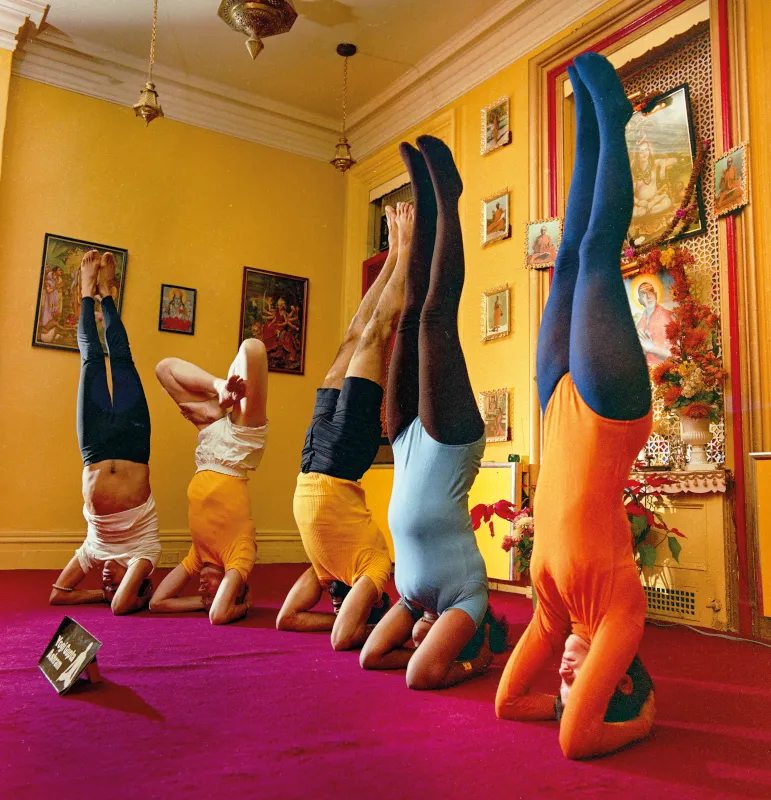

At a time when most photographers were committed to black-and-white, Slavin’s embrace of color became a defining element of his work. For him, color was not merely a stylistic choice but a vital tool for rendering the nuances of reality, making it an important dimension in his exploration of social life. His portraits—whether of business professionals, quirky fan clubs, or church choirs—go beyond surface appearances, revealing the shared experiences and subtle tensions within each group.

Throughout his career, Slavin has been fascinated by the wide variety of communities that shape American life. His work reflects this diversity while serving as a rich visual study of the human need to connect. His portraits are heartfelt explorations of human connection, reminding us of the joy and significance of being part of something larger than ourselves. Each image tells a story of identity, belonging, and the shared humanity that unites us, making them as emotionally resonant as they are visually striking.

The original release of When Two or More Are Gathered Together in 1976 marked a significant moment in color photography, capturing the complexities of American social life and sparking critical discussions about community. Fifty years later, as the United States faces profound social division and political unrest on the eve of a presidential election, the expanded anniversary edition published by Damiani Books revisits themes of social unity with new subjects and an insightful essay by art historian Kevin Moore that contextualizes this important body of work.

In this conversation, we delve into what inspired him to focus on groups, his shift to color photography, and how these collective portraits speak to the complexities of identity, belonging, and the broader American experience. Slavin reflects on the evolving cultural landscape, his unique approach to portraiture, and the powerful narratives that emerge when two or more are gathered together.

Jelena Martinovic: You have been taking group portraits for the past 50 years. What first drew you to photographing groups, and what do you think happens when two or more are gathered together?

Neal Slavin: I was at a friend's house who was working on opening credits for a movie, and she asked me to bring snapshots of my family from the 50's. They were all black and white pictures. As we want over them, one picture caught my eye—a panoramic view of a Boy Scout troop featuring my brother-in-law. I cannot, for the life of me, understand why I was attracted to that picture out of all the pictures I brought. I remember looking at it and wondering, “Whatever happened to these boys?” It had been 12 years since the photo was taken, and for some reason, this one stood out to me the most. It was all about memory—who they were and where they were now. Then I looked more at it and realized it was a fantastic photograph.

Visually, the photograph was extraordinary because of the uniformity—they were all wearing the same uniforms, and the repetition of tone and shape caught my eye. I noticed the different expressions on each of their faces, which told me a whole story. I was in a receptive mood, searching for my next project, and this image struck me deeply. The very next day, I called a friend who worked for a volunteer ambulance corps and asked if I could photograph their group, and he agreed. I told him to bring the ambulances out with all of their trophies-they had ambulance races at that time for which they would receive them. The picture was not too good, however, I knew then that I had stepped into something very meaningful. When I looked at the black and white picture, I couldn't tell the difference between a silver trophy and a gold trophy. It looked exactly the same. But when I looked at the color, it was all there. All this information hit me, and I asked myself, “why aren't I working in color?”

JM: So, it added a whole new layer of meaning.

NS: Totally! I realized then that I had to work in color. It wasn’t just about aesthetics; color became a form of information. I remember reading that Cartier-Bresson avoided color because he felt it conveyed too much information, but I found that I wanted as much information as I could get. So, I joined a small group of photographers in New York who started working in color. At that time, in order to be recognized, you had to work in black and white, but we refused. We took the criticism of working in color and we all went our way with our work. The color opened an entire world for me.

JM: It must have been challenging to push through with color photography in its early days. How did you manage that shift?

NS: For me, it wasn’t too challenging because I had been doing commercial work in color. However, the challenge was how to make various pictures of these groups in color and make it work, make it mean something. But I just did it. Once I understood that color was information, I didn’t look back. I didn’t overthink it; I just kept moving forward with the work.

JM: Your photographs feature a wide range of groups, from hot-dog vendors and fire department chaplains to pug owners and Star Trek conventioneers. How did you select your subjects?

NS: At first, I was finding them myself. I started with groups that fascinated me, that I felt expressed something. The first group I did was a Twins Association and then a group of blind people. Afterwards, I laid the photographs out and realized they were talking to each other. There was a connection. between all of the images. The 1960 and 1970s was a heady time—everyone was moving to SoHo, and there was an energy in the air. All we wanted to do was to have big spaces to work in, to paint in, and in my case to photograph in.. America was turbulent at that time. There was so much going on in terms of the Civil Rights Movement, etc. I realized that these group portraits were more than just pictures; they were a way to make a statement about America. It had never been done before the way I wanted to do it.

August Sander, the German photographer, was my role model for this. He set out to photograph the entire German people before the war. For example, he would take a photograph of three ministers to represent all the ministers or one soldier to represent the whole army, etc. I thought I would like to do something similar in America. Not literally, of course, but by photographing different groups to represent segments of American life. So, I began photographing groups like the American Begonia Society and found it much more meaningful than photographing a single person. In a group, each person has their own expression, their own body language, and together, they create a symphony of people in a single group. No two people were alike. Someone would put his shoulder up front, while someone else would turn to the side because he did not really want to be photographed. There was a narrative and a story within a group of people. Multiply that with tens or hundreds of pictures, ...what a portrait that would make!

As the project grew, it became too big for me to manage alone, so I hired a researcher to help find the groups. This was an enormous task, but she found them, and the work kept expanding. I could see in my mind that it was growing.

So, this is the second edition of the book, which originally came out in the mid-70s. The reproduction quality wasn’t great back then, but younger generations have discovered and loved it, which is fascinating to me. It means that it has stood the test of time. The new book is an expanded 50th Anniversary edition of the original, featuring additional work I’ve created since the 1970s up to 2023. Kevin Moore, the editor, wrote an essay for the book that I believe truly captures the essence of the work. He understood it well, and his writing encapsulated many of the ideas behind the photographs.

These photographs are about the human need to be together. They show that we support one another, that we belong together. At a time when America is so divided, these images address that fundamental need for connection—whether it’s a handshake, a hug, or simply being part of something larger. It’s human nature, and that’s what this book is about.

JM: I’d like to address what you’ve just said about the human need to be together. While America is often viewed as a land of individualism, you argue that groups are the true American icon. How does your work challenge this traditional notion of individuality? Additionally, how do these portraits reflect broader aspects of American culture and society?

NS: I'm going beyond that. In the 19th century, there was a Frenchman, Alexis de Tocqueville, who came to America and observed (in his book ‘Democracy in America) how remarkable it was that Americans of all ages joined together in various organizations which he called associations. At that time, everyone worked in small groups. He thought it was unique (to America) because he came from a society where a king or queen decided what was to be done. In America, nobody ordered things; people simply collaborated in groups. De Tocqueville believed that it was a true American way of life, and that for democracy to survive, it would be through the idea of groups gathering to pursue shared goals. I was very impressed by this, and when I read it, I felt I was on the right track with my photography.

At first, I was captivated by the great, quirky, serious people coming together. People often ask me how I managed to bring them together for my photographs. My answer is simple: you just do it. I didn’t realize at first the significance of what I was embarking on. I began to understand that having your peers is essential for a fulfilling life. You need to relate to people, and that’s very rewarding.

For example, I have a morning coffee group that used to have 15 people. Now, due to Covid and relocations, it's down to four or five of us. If I skip that gathering and spend the whole day in the studio, I feel empty. I started realizing the importance of social connection. I was contacted by various sociologists who connected with my ideas and wanted to discuss these for their books. They wanted to explore the notion that we’re not alone and that sociologically, people need to interact and communicate with each other. The takeaway is that we are more alike than different.

JM: Your work explores this tension between individuality and group belonging that we have already discussed, but also between the identity one holds and the identity one presents to the world. How do you navigate these complexities in your portraits, and what insights have you gained through this exploration?

NS: My book BRITONS (Andre Deutsch) was a very different form of presentation, using a huge Polaroid camera. People present themselves differently to that camera than with a smaller one like Hasselblad or Leica, like in When Two or More are Gathered Together. It’s like when you’re at work, and at the end of the day, you change to go to a party—there’s a different presentation of yourself. We have a private persona and a public persona. In group portraits, the public and private personas come out, and sometimes people don’t realize how their body language reveals things. I love that about photographing groups—it all unfolds in front of my camera.

When I set up a picture, I don’t tell people where to stand. I pick a space I think will fit the group, and then I ask someone who knows the group to arrange them, because they understand the dynamics. In those 10 or 15 minutes when I’m photographing, I will have an intimate relationship with those people, but then it’s over. But in those 10 or 15 minutes, a whole world is presented to me, and I find that fascinating. The difference between an individual and a group is there, but at the same time, it’s not. If I photograph someone individually, they would present themselves in a certain way, but when they’re in a group, there’s a subtle shift. They won’t change completely, but they will alter just enough to present themselves differently in front of the camera. Everyone has their two sides.

JM: Can you walk us through your working process? How do you prepare for a shoot, and what steps do you take to capture the essence of each group in a single frame?

NS: If possible, I like to visit the location beforehand, but sometimes it’s not possible—like when I’m shooting in Muncie, Indiana, and I’m from New York. So, I plan the space in advance, lighting it accordingly, even without the people there. I use an assistant to stand in different spots to get a sense of the layout. Once the group arrives, the director or head arranges the people. I don’t get involved in that because I don’t know the group dynamics. If I were to arrange them myself, there would be something false about it. I enjoy this process because you see the group coming together, watching as they adjust and interact with each other. Then, I just observe and start shooting.

JM: How has this approach influenced your final images? Were there any surprises in how groups chose to present themselves?

NS: There are always surprises. When the picture is done, I look at every single face as if under a microscope. When you're looking at every single face it's fascinating on its own. There’s always someone smiling that I didn’t notice or someone frowning, or someone looking away. These unexpected moments give the image a heartbeat that wouldn’t be there if I had ordered them around. When you try to direct people too much, you lose that life force. The best portraits happen when people are allowed to be themselves. If I put my heart and soul out there, they respond to that. That’s what gives the picture its energy.

JM: Which shoots presented the greatest challenges? For example, while looking through the book, the photograph of the NY Stock Exchange particularly stood out to me in that regard.

NS: Oh, that’s a great one to choose; it was a memorable one! We started working at 4 PM, setting up the cameras and lights, and finished at 5 AM. We started again at 7 AM, since we had to be ready by 9 AM because the stock market opens at 9:15, and we only had 15 minutes to shoot. There were about 10 or 12 assistants helping. As everyone was leaving for a break, I realized the front row wasn’t lit properly. So, I added some soft lights on the floor to give them an underlight. One of the assistants, a young guy, came over to me, absolutely hysterical, telling me I couldn’t put lights on the floor. He’d learned in school that lights always had to be on stands. I just told him, “Well, this is a different school.” So, one of the memories of that shoot is this kid telling me I cannot put lights on the floor. (laughs)

But yeah, that was quite a shoot. It had 500 people, and you can go through each one and find that no two are alike looking up the camera. You can do it forever and explore different sections of the photo. I had a show a few years ago where the gallery told me that they had never experienced people spending that much time in front of a photograph. They would sometimes spend half an hour going through it, looking at every single face, every little detail. And this is what I want them to do because in that looking, there's a whole world that you discover, and what you really discover is that people are together. I am a person who is about WE, not I. That’s my mantra.

JM: I think that’s a beautiful mantra that centers the community.

NS: Absolutely!

JM: There’s a lot of humor in your work, blended with profound social commentary. What role does humor play in your portrayal of these groups?

NS: Humor is big in my work, but it’s found humor. I don’t tell people to laugh or smile. The best kind of humor is when you discover it naturally. My work isn’t funny—it’s quirky because life is quirky. I laugh with people, not at them. That’s a huge difference. If you laugh together, it’s okay. If you laugh at someone, that’s not right. I find these little quirks in people that I love, and I photograph them with appreciation, not mockery. For example, if I see someone wearing a quirky hat, and if I were to photograph him, I wouldn’t say, "You look funny in that hat." That’s already putting them in an uncomfortable position. Instead, I might ask, "Can I take a photo of you because I love your hat—where did you get it?" And I would really mean that. You get a certain amount of truth and honesty when you approach people that way as a photographer.

JM: The new edition of the book features fifty-four additional photographs taken since the original book was published. How challenging was the editing process, and how did the new photographs contribute to the overall narrative of the book?

NS: It’s essentially a continuation, but there’s growth in the subject matter I’m choosing. For example, the photo with the pug owners—I’ve never really done a portrait of dogs before, and I love that one. I’ve never explored that area before. There is a lot of growth in other areas as well. Growth is about not sticking to the same patterns, even though some may think that’s what I do.

Currently, I’m working on a series of projects for a new book on prayer. What does it mean to gather and pray? What does that look and feel like? This work is very different from my previous projects because it lacks quirkiness; it’s not humorous, but the subject matter is fascinating.

JM: How do you approach this current subject of prayer, as compared to your group portraits?

NS: The gatherings I document occur during this ceremonial time, and I’m capturing what I see. I work hard to ensure each picture stands out on its own, but they also need to communicate with one another. If they don’t connect, I stop working. In fact, we recently laid out ten 50-inch-wide pictures on easels in my studio, and they really did talk to each other. It was surprising. If you ask me to describe that connection, I can’t pinpoint it, but there’s definitely a relationship between the individuals in each image. Ultimately, it’s less about religion and more about the realization that we are more alike than different, regardless of our beliefs.

JM: That’s a very poignant takeaway.

NS: Absolutely, and I think we need that insight now more than ever. It’s all fascinating, especially in these chaotic times when the whole world has gone crazy. We need much more than I can offer through these photographs, but in my own small way, I tried to make a statement that resonates with the world.

JM: I would say that is precisely the role of art—to illuminate what often goes unnoticed and help us imagine other ways of coexisting.

NS: Yes, exactly. That is the role of art. If anyone is willing to truly look at photography, they’ll discover a world waiting for them, one that can profoundly change their lives.

JM: Since the original publication of When Two or More Are Gathered Together, how do you think the nature of groups has changed, especially in the context of modern social dynamics and online communities?

NS: Unfortunately, it’s not for the better. Let me put it this way: I walked out of my building one day and saw two teenagers. One was across the street, and as the other crossed over, he turned his head and said, "I'll see you online." That moment struck me. Just like the two of us—we are seeing each other right now, but there is a screen between us. It creates a distance that impacts our relationship.

This disconnect is indicative of our current environment. Platforms like Instagram and Facebook create their own massive groups, where rejection can lead to devastating consequences. I've seen young people feel so isolated and hurt by not receiving enough likes or acceptance from these large online communities that they’ve tragically taken their own lives.

Being part of a group now feels precarious. For instance, if someone in a group says something negative about you and you’re suddenly pushed out, that rejection can be more hurtful than the joy of that you felt when you joined the group.

I think it’s no longer a group anymore. Am I going to try to photograph a group on Instagram? No, because it lacks the essence of a true connection. I can’t touch you, shake your hand, or give you a hug. Those fundamental human interactions are absent. And what a perfect time for AI to step in and try to fill that void, right?