Courtesy Nour Zoghby Fares

Courtesy Nour Zoghby Fares Nour Zoghby Fares is an architect, artist, PhD candidate, and mother of two young children who runs a ceramics studio, Fabrica Design Platform, in Beirut, Lebanon. At Fabrica, Nour works with more than 650 students; the oldest student is 85, and the youngest is three. The historic building where Fabrica is sited is a charming one: It's inside the Dar Khawla Building, which is named after Nour's grandmother, Khawla Rizk. Fabrica is just off of General Foaad Chehab Road, not far from the Nicolas Sursock Museum. On the ground floor, Nour's mother operates a small shop called Nour Artisan where she sells art, fashion, and homegoods produced by local artisans. The staircase that connects Dar Khawla Building's floors is itself a gallery. There, a beautiful, bespoke object offers small podiums where artists can display their sculptures. Wonderful drawings line the walls, and ornate floor tiles bring warmth and geometric wonder to the space.

Remarkably, Nour kept Fabrica open through the ceasefire that was passed on November 27th, albeit one that Israel quickly violated when it bombed the Lebanon-Syria border region. Her ceramics classes became three hour long escapes for people in Beirut looking to zone out, mold clay into pottery, and simply talk about what they were feeling. "We haven't closed. Not a day," Nour told me over Zoom just hours after the ceasefire was reached. "I didn't want people to deal with, you know, the sound booms we were hearing that were terrifying for all of us. It just doesn't get easy. It's crazy when you think about it. There were bombs coming down right next to us. And people were just living their lives."

"This was pretty challenging for many reasons, if I am being honest, on an economic level too," Nour said. "A lot of small businesses had to close down completely because there was zero income, and costs were so high. I feel really grateful, actually, that we were able to open our doors for everyone who wishes to come. Sometimes, our classes had just one student. There was no way I was going to close class if there was a student there. 'If the student wants to come, let them come,' we said. For three hours, during this war, we can forget everything here."

At Fabrica, students "talk about their lives," Nour told me, while shaping clay into vases, sculptures, and whatever they please. "One of the main topics people talked about was what they were going through. I feel like Fabrica was a way to disconnect. The kids shared their personal experiences about what they were going through. People help each other out when they talk about these things. It was therapy, in a way. For me, I was constantly stressing, 'How can I help?' This is a terrible feeling because, on a large macro scale, you feel like what you do doesn't have much of an impact. But watching people open up and talk about their lives brought me happiness and satisfaction. I hope it means something.”

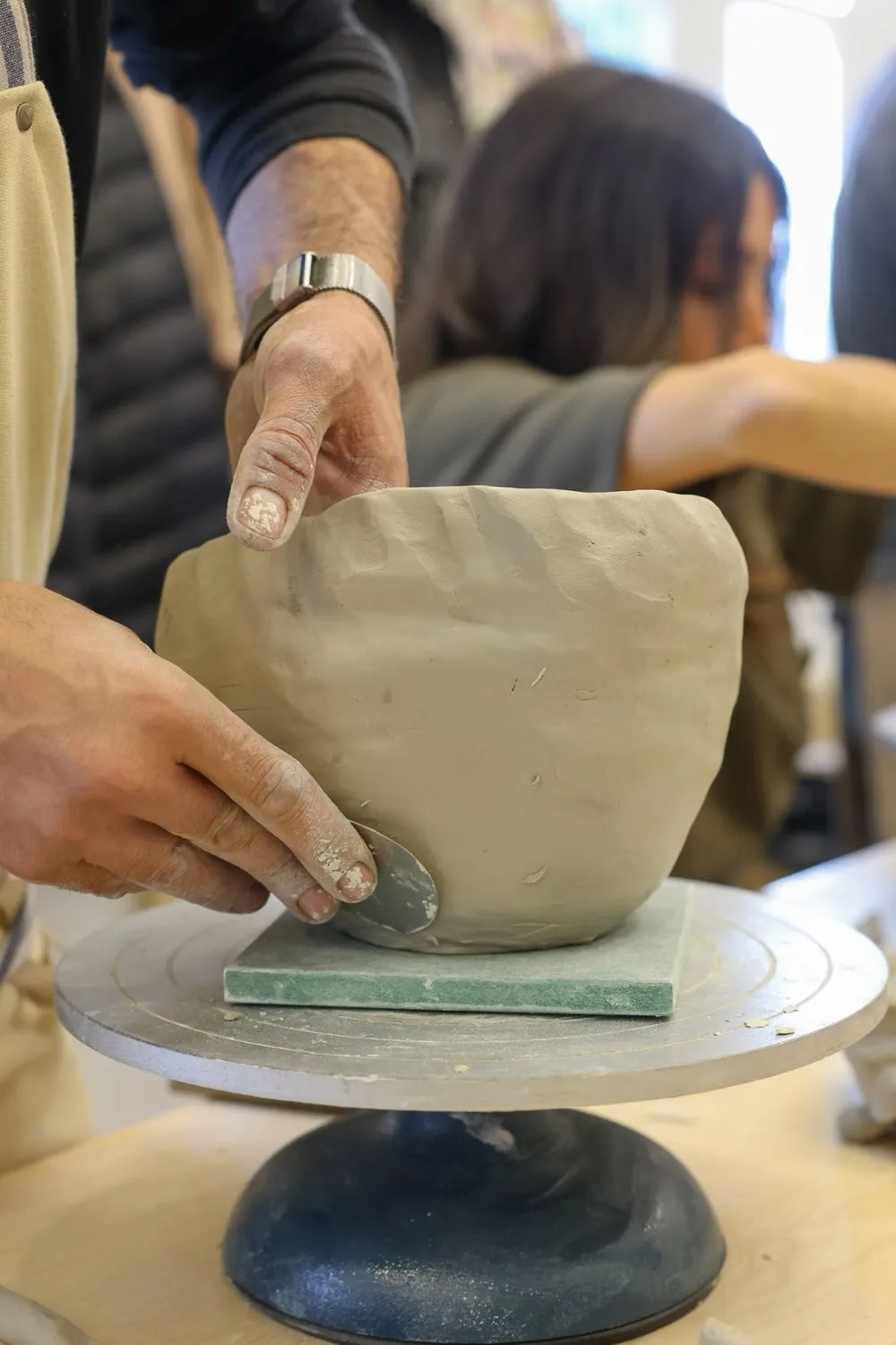

"Something happens when people sit down for three hours, and make something with their hands," Nour continued. "The second you use your hands to touch the Earth, with your muscles, this releases a sense of relaxation. People just start working, and they don't talk about anything. They're just in this zone. And they don't want to talk about anything. When you look at them, it's nice. You know they're into it. It's the tactile nature of the clay, and how we interact with it using our hands," Nour continued. "We have a very big network that depends on us economically, but also emotionally and psychologically, so we had to be creative and innovative. We represent local artists by promoting and selling their works. But we also work with many local suppliers for materials, glazes."

Nour noted that many people left Beirut for the mountain region outside the city, and the country more broadly, when the shelling picked up. We saw this happen in the early days of Israel's wanton bombing campaign, when Beirut's central arteries were clogged with traffic. People were desperate to get out. "I have a lot of friends that left,” Nour said. "Some people just left and started their lives elsewhere, you know. They said, 'We're not dealing with this anymore.' They registered their kids in other schools, and found other temporary solutions. They worked remotely. And then there were the people who stayed in Lebanon. You had people who stayed in Beirut, and you had people who were going to work in Beirut, and sending their kids to school in Beirut."

After a few weeks into the bombing campaign, Nour herself eventually left Beirut for the mountains with her husband and two children. But Fabrica kept its doors open, and Fabrica's employees kept teaching, even if there was just one student in class that day. Nour also began selling artworks from Fabrica to raise money for meals, which was the most urgent thing, because "people didn't have anything to eat," she said. Nour and her team eventually sent food to cities and towns all over Lebanon by selling art by Alain Vassoyan, Charles Khoury, Léa Bou Habib, Majdoline Hattoum, Nay Rouhban Yafi, Nayla Abi Yaghi, Nicole Abou Farhat, Pascale Harres, Patricia Assaly, Stéphanie Boueri, Vanessa Dammous, Zeina Bacardi, and Zouhair Dabbagh. They also also figured out clever ways to teach ceramics classes for students who left Beirut.

"We got creative to address what was happening," Nour said. "We created these art kits so people could make their own ceramics, wherever they were. And we started delivering the art kits to our clients' homes, so they could work from there. And then we would go and pick them up, and fire them for the students, and then send them back to their homes for glazing. The older generation isn't really familiar with Zoom, so we coordinated everything on WhatsApp. To assist people, we did voice and video calls. We made a document that explains how to use the art kit, a simple 2-page form. In the document we talk about how the art therapy kits can help relieve stress."

For Nour, the post-ceasefire agreement offers a slice of respite for reflection about the past, present, and future. "A lot of Lebanese people cannot hear this word 'resilience' anymore. Honestly, they're sick of being resilient, you know," Nour said. "It's like, especially with our government, they can throw anything at us, and we can put our feet back on the ground and get up. Everything goes on the next day, which is somewhat beautiful, because we have a very strong sense of community, in both our businesses and our families. We are all here for each other. But we've gotten to a point where academics and scholars are like, 'What is this resiliency getting us? We should kind of also stop being resilient, right? Maybe we should start resisting our government?' I feel like these things aren't either/or. We can find a balance between these traits of resiliency, which are important for our characters. This is something I think has happened at Fabrica."