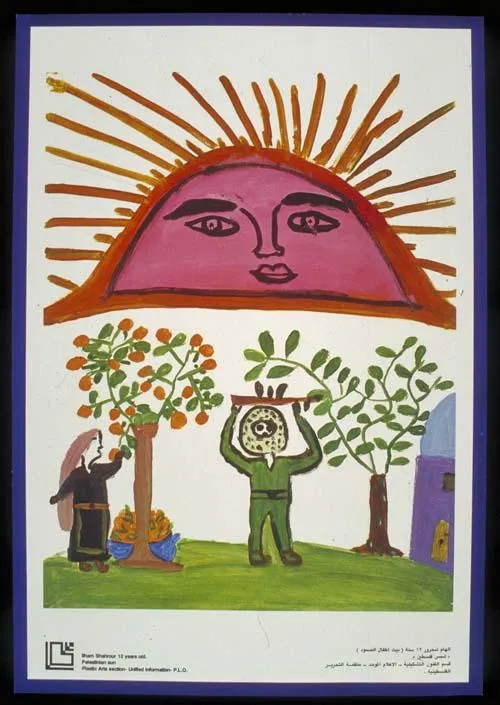

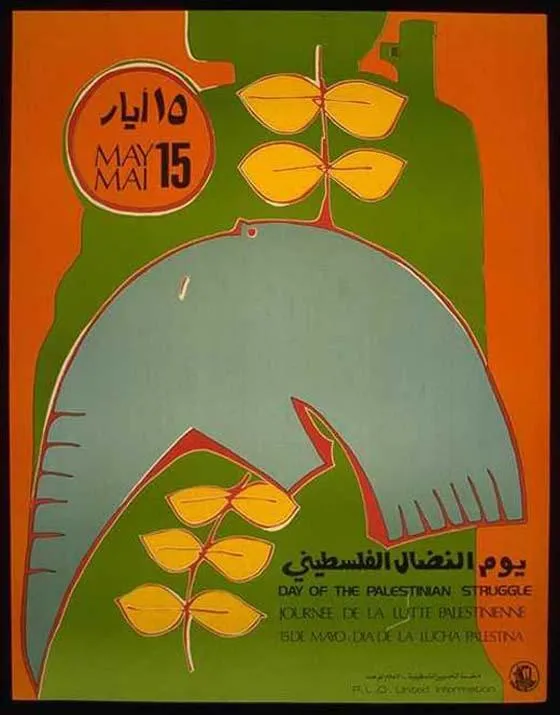

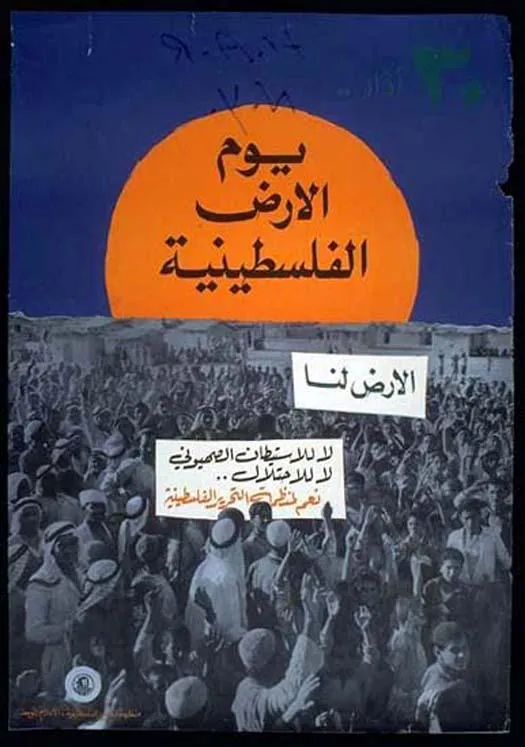

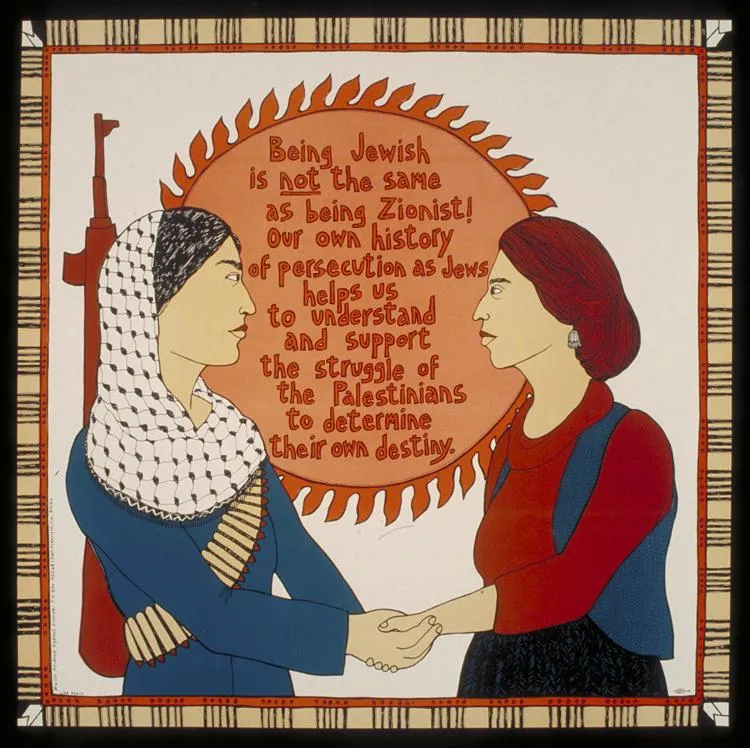

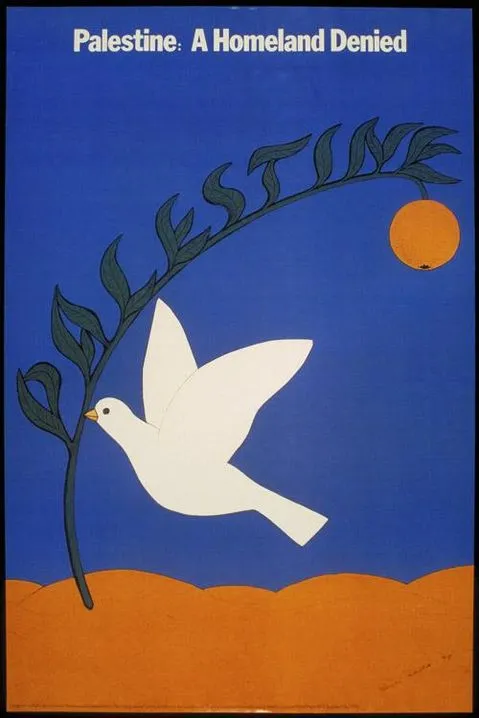

Marc Rudin, The Nakba Remembrance Day, 1989. The Palestine Poster Project Archives.

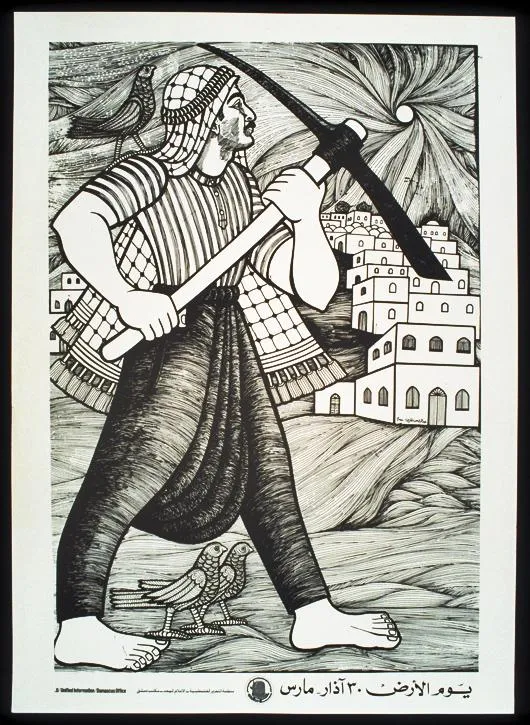

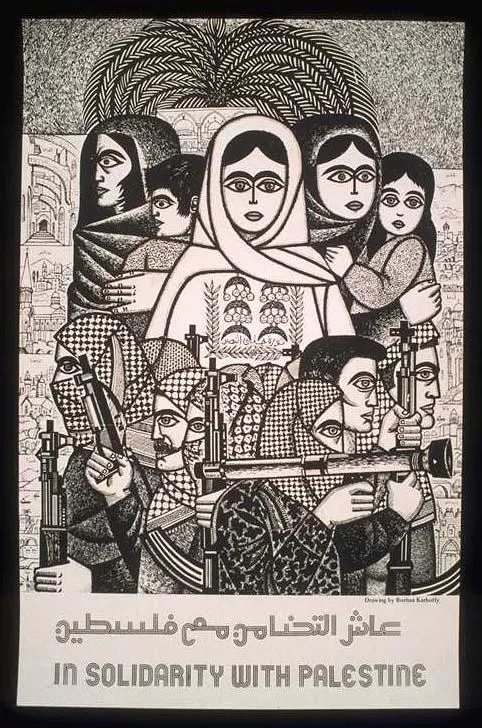

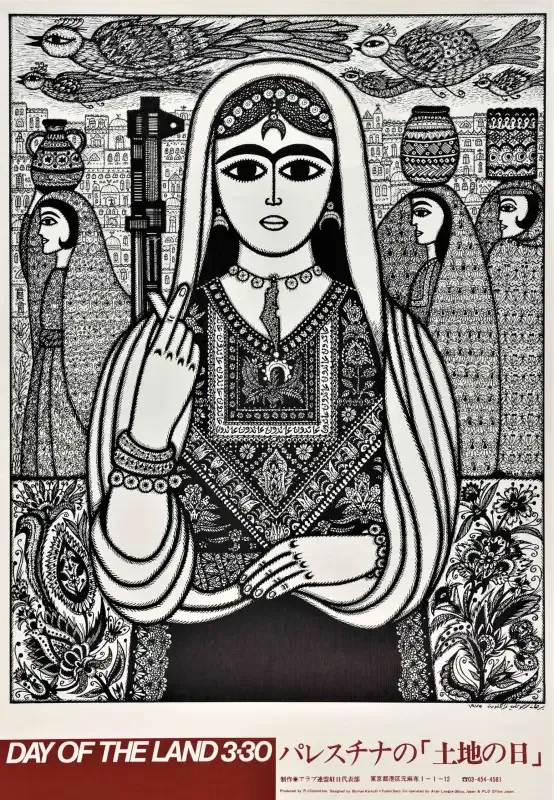

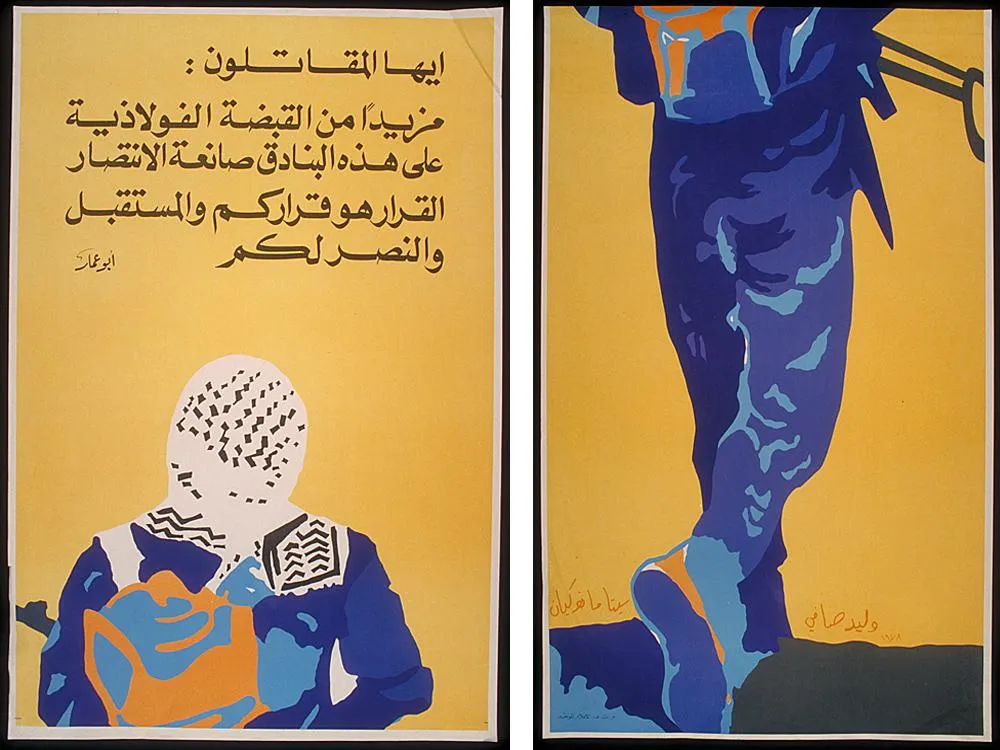

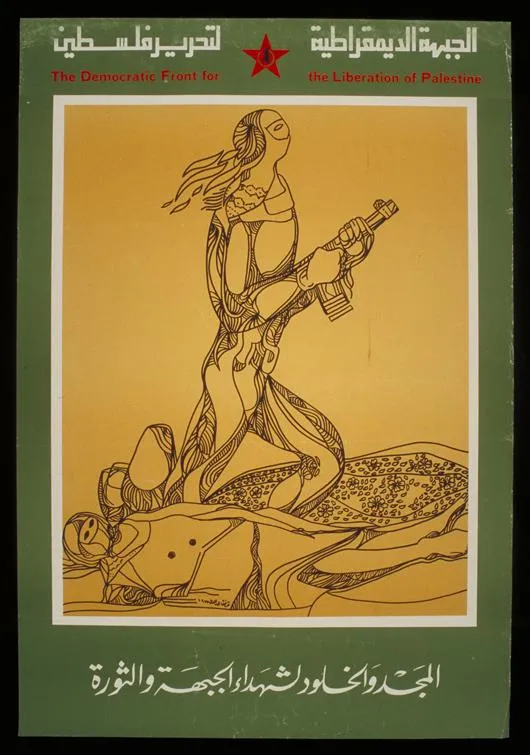

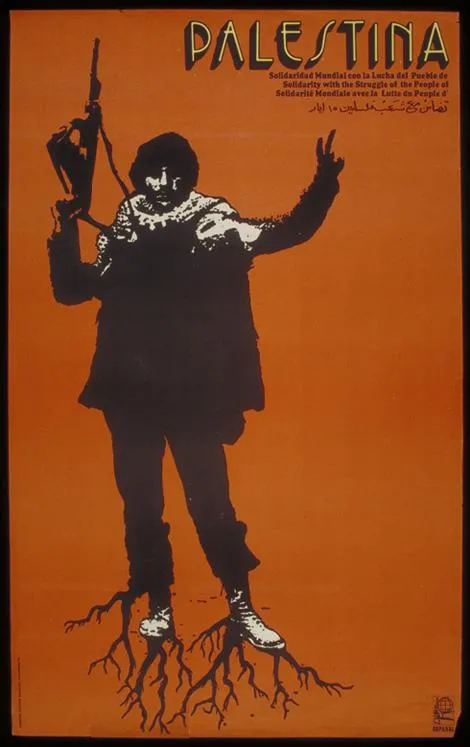

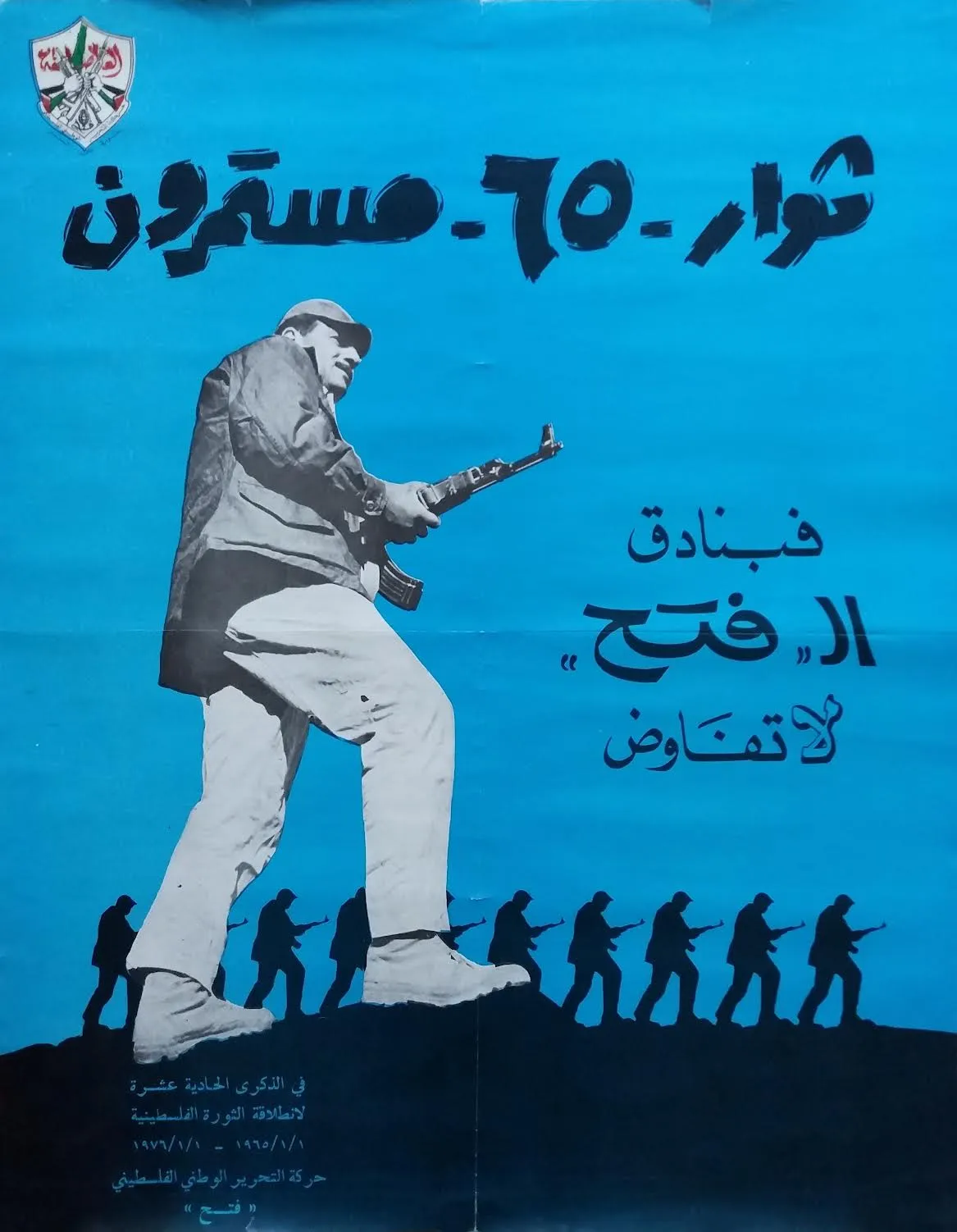

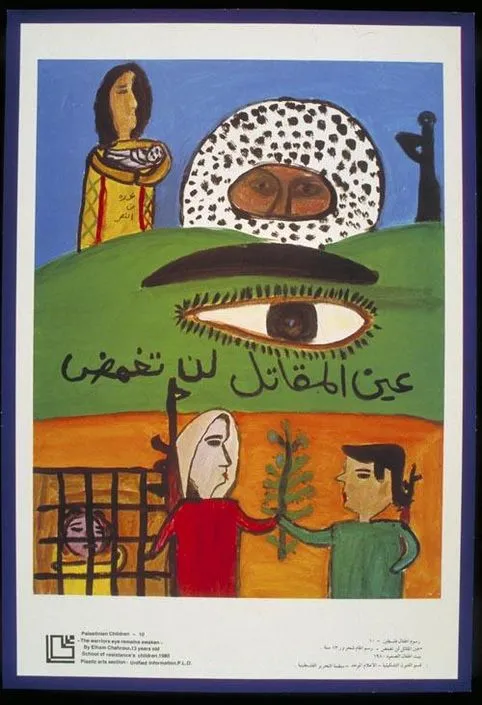

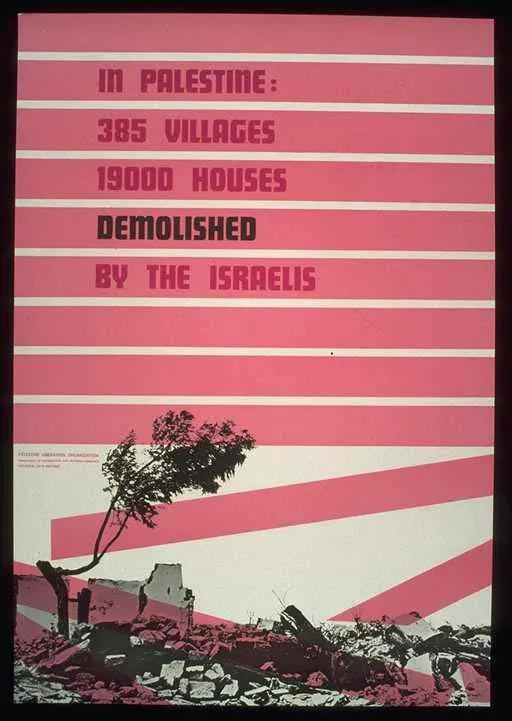

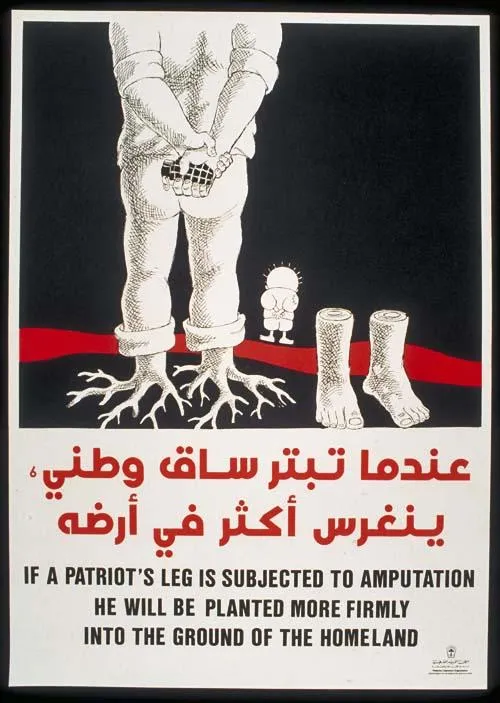

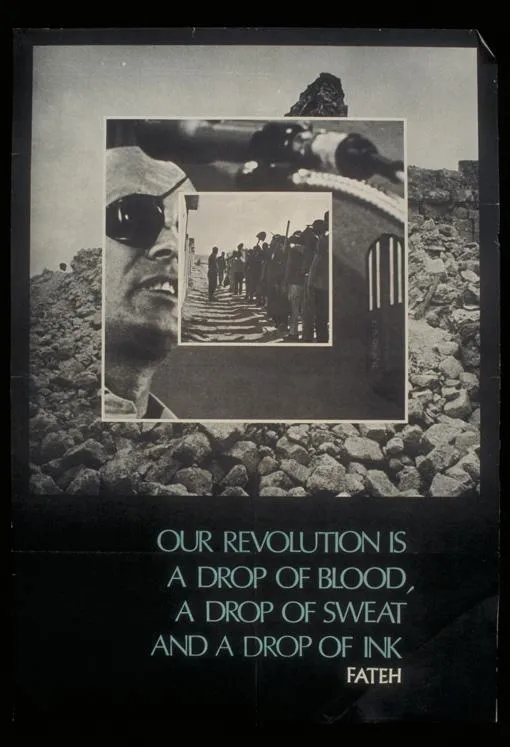

Marc Rudin, The Nakba Remembrance Day, 1989. The Palestine Poster Project Archives. For decades, Palestinian revolutionary posters have served as a defiant visual language—proclaiming identity, hope, and resistance against occupation and exile. These graphic works have become enduring symbols of expression, embodying the spirit of a people's struggle for justice and freedom. Instigated by the post-1948 adversarial climate, the need for artistic, political, and insurgent expression arose in the form of powerful, easily understood, and swiftly distributed graphic visuals that conveyed the spirit of the fight. Palestinian posters provided a way to rebel, maintain hope, and sustain a collective identity during a decades-long fight for freedom—an act of rebellion and a manifestation of resilience through art.

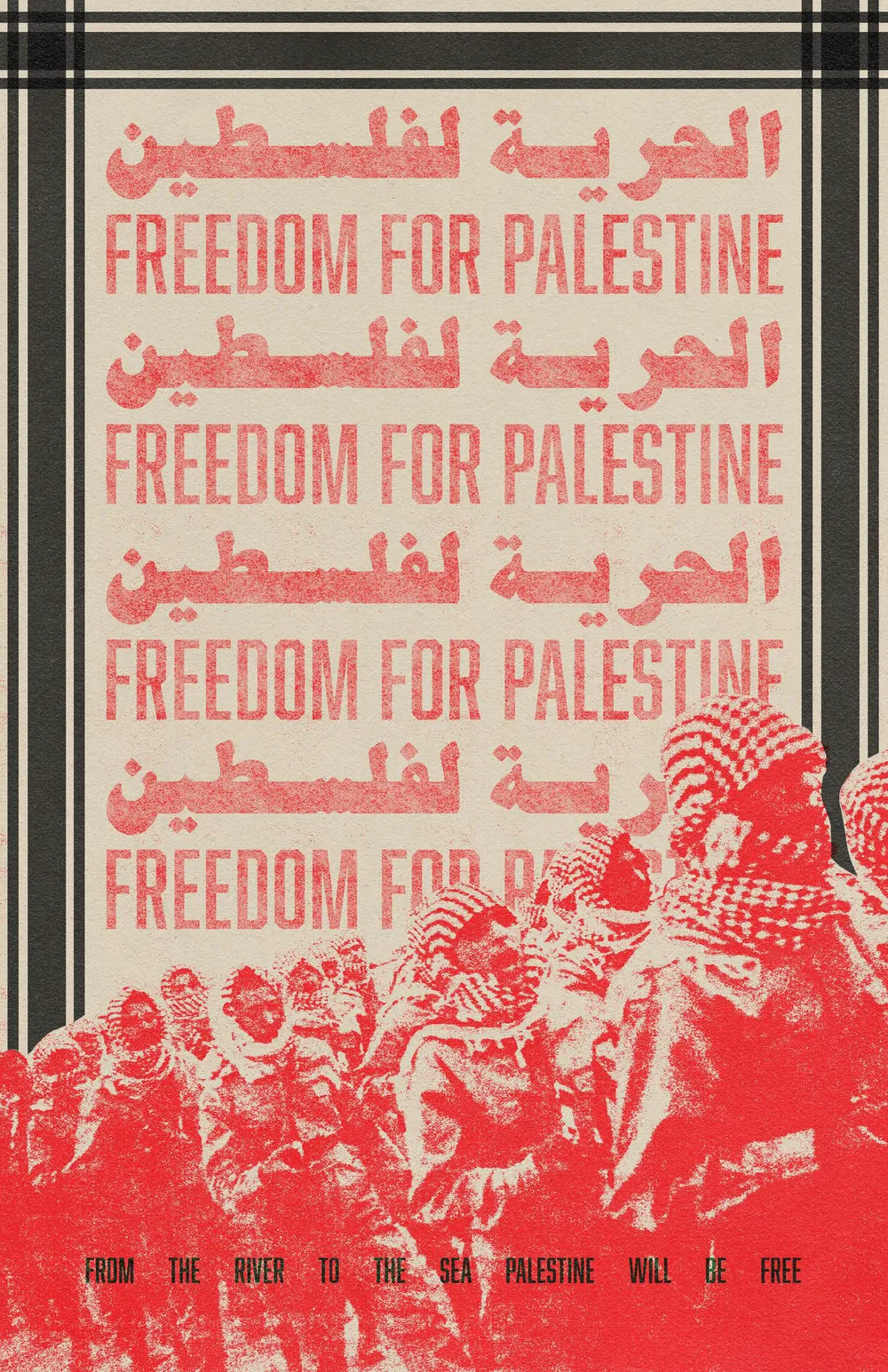

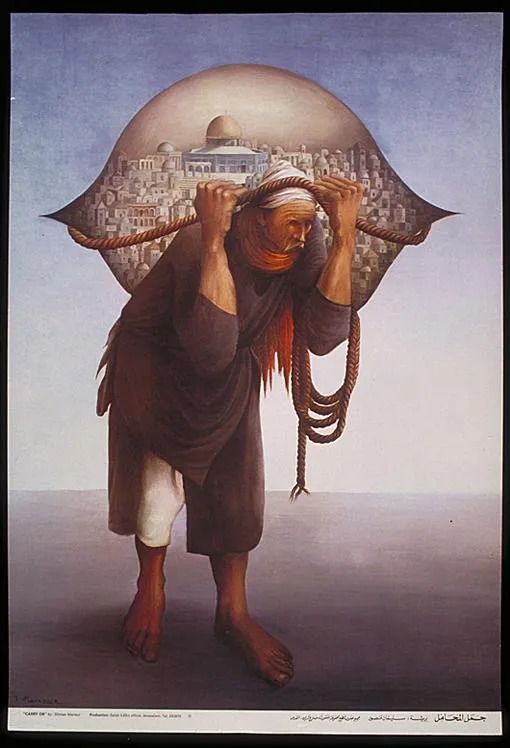

As genocide continues in Gaza and the West Bank, pushing the Palestinian people toward further devastation, the urgency of revisiting the historical vocalizations and visualizations of their struggle for freedom becomes ever more clear. Driven by the aftermath of the 1948 war, Palestinian artists felt the urge to respond to a constellation of a community dislocated, scattered, disrupted, and decimated. Adapting to their new reality, Palestinian artists regrouped, finding the strength to voice their revolt in revolutionary posters that bolstered their national and religious identity, providing hope for liberation and peace.

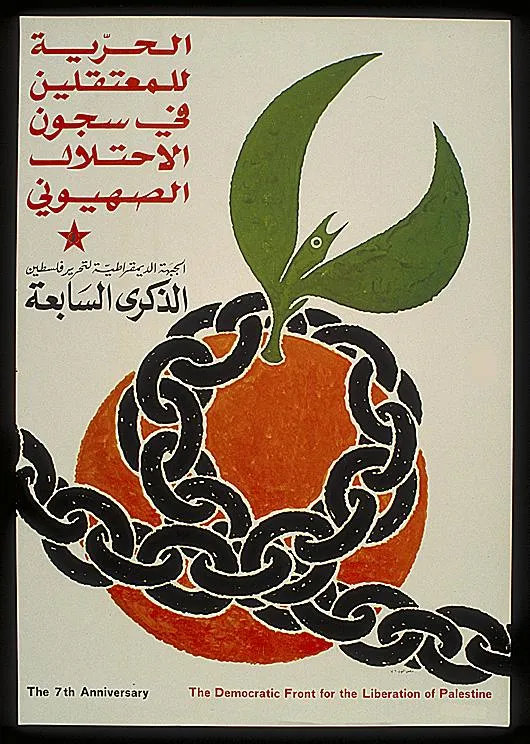

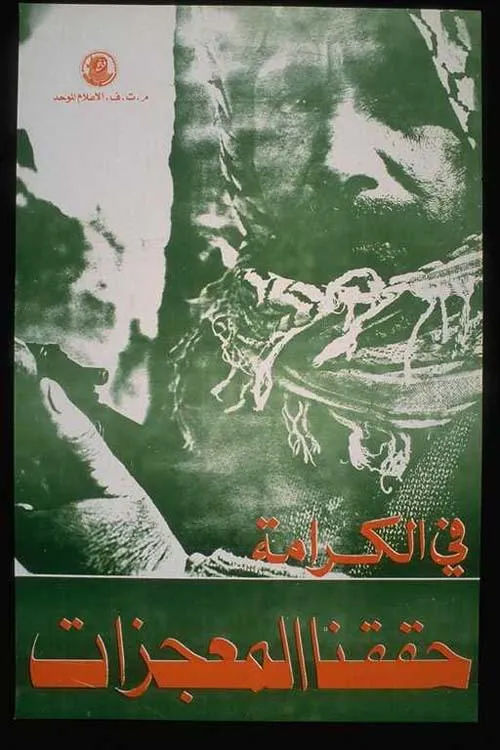

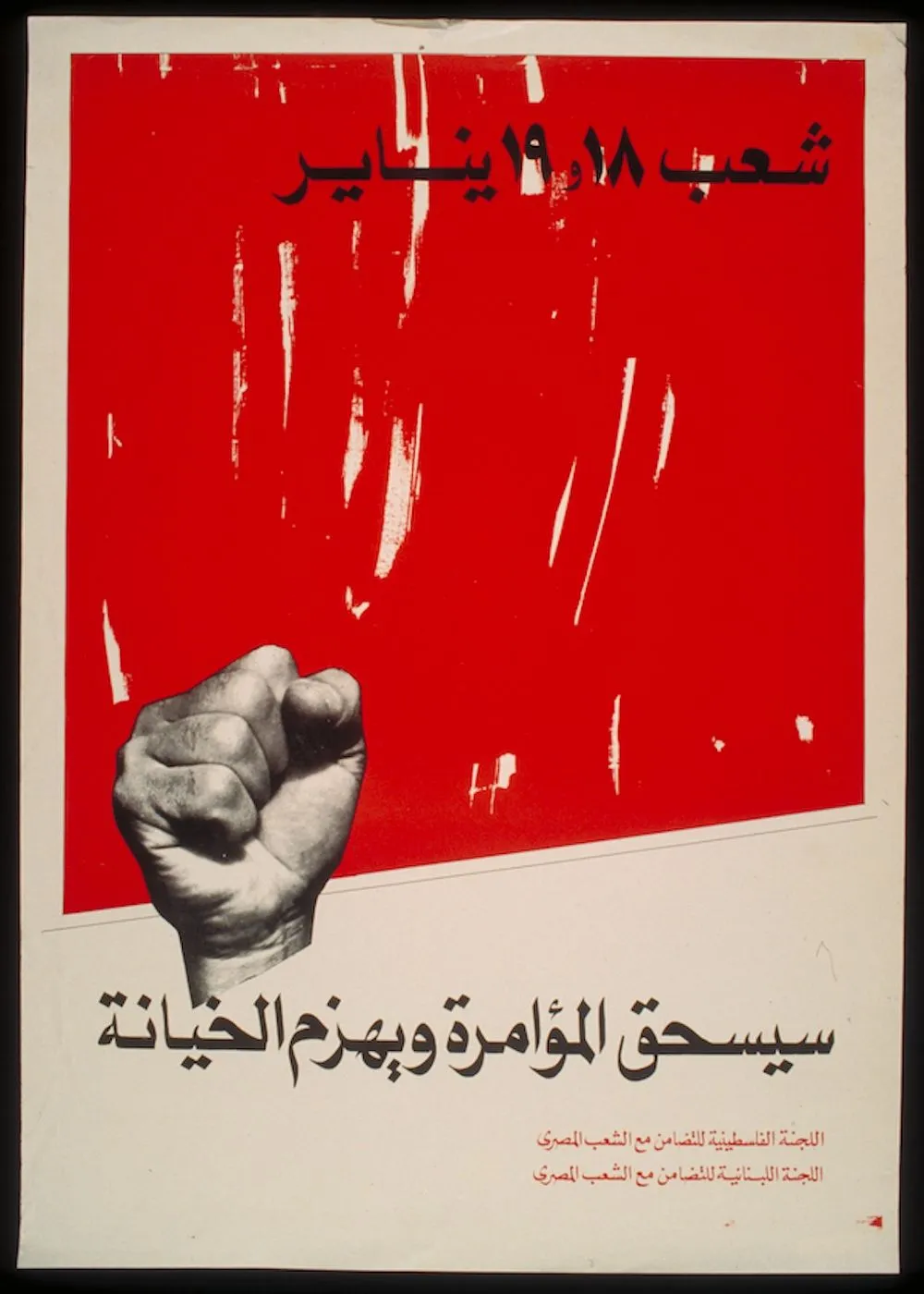

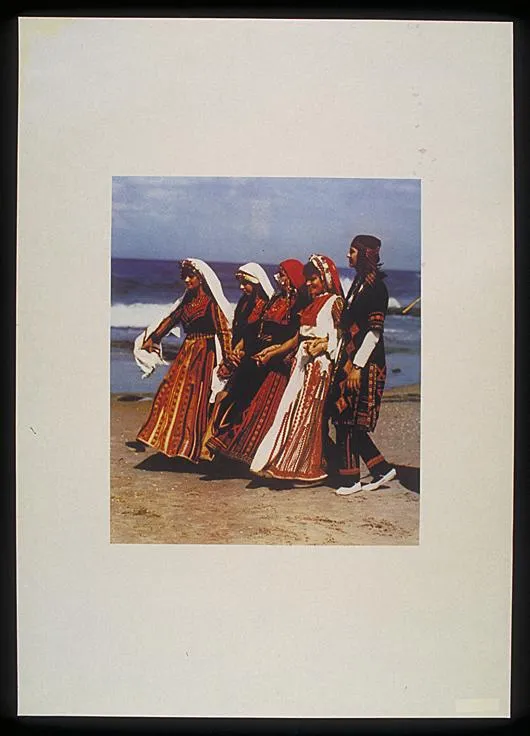

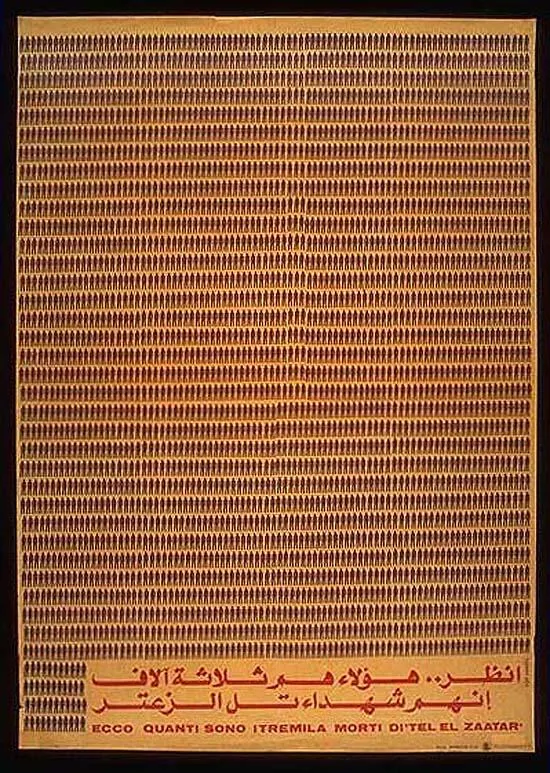

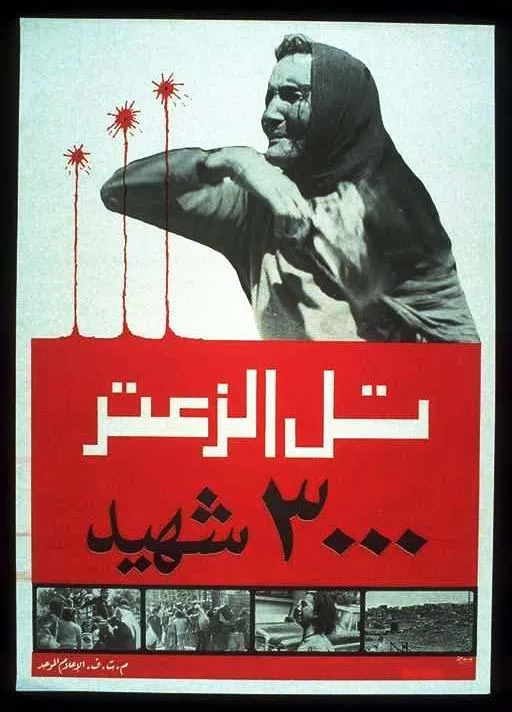

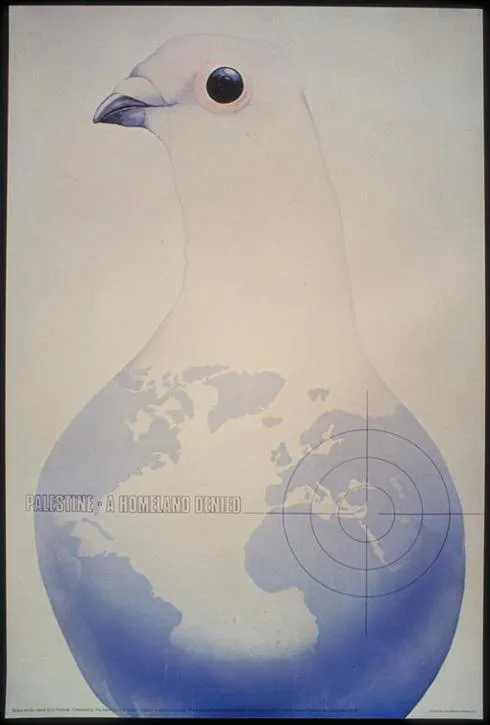

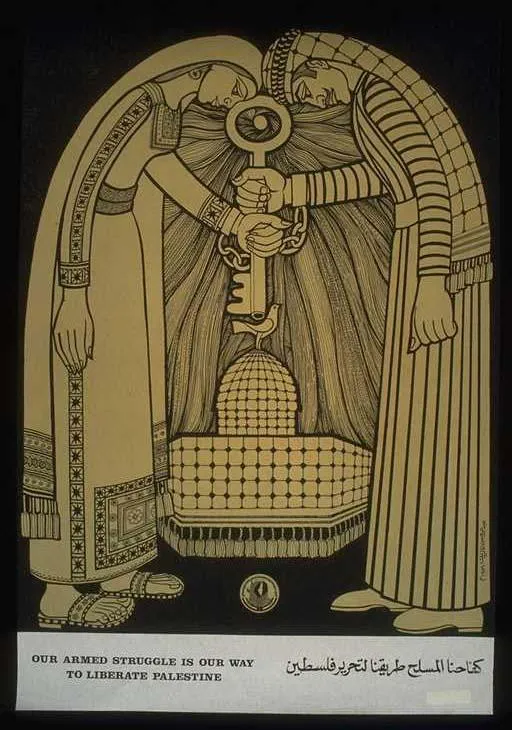

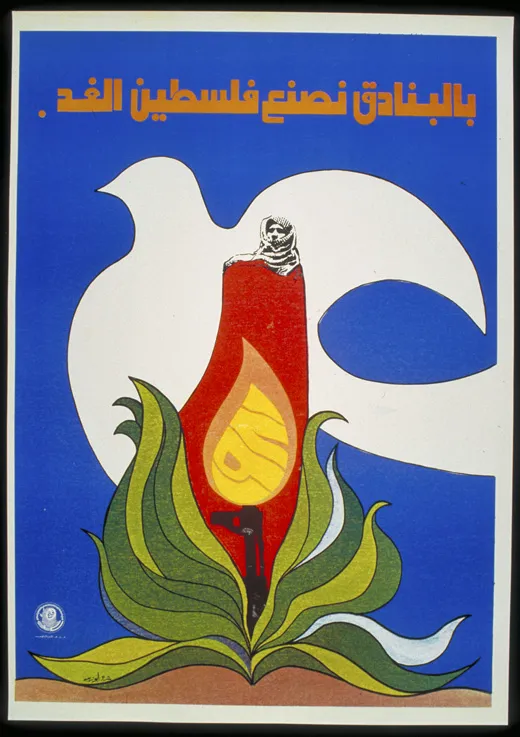

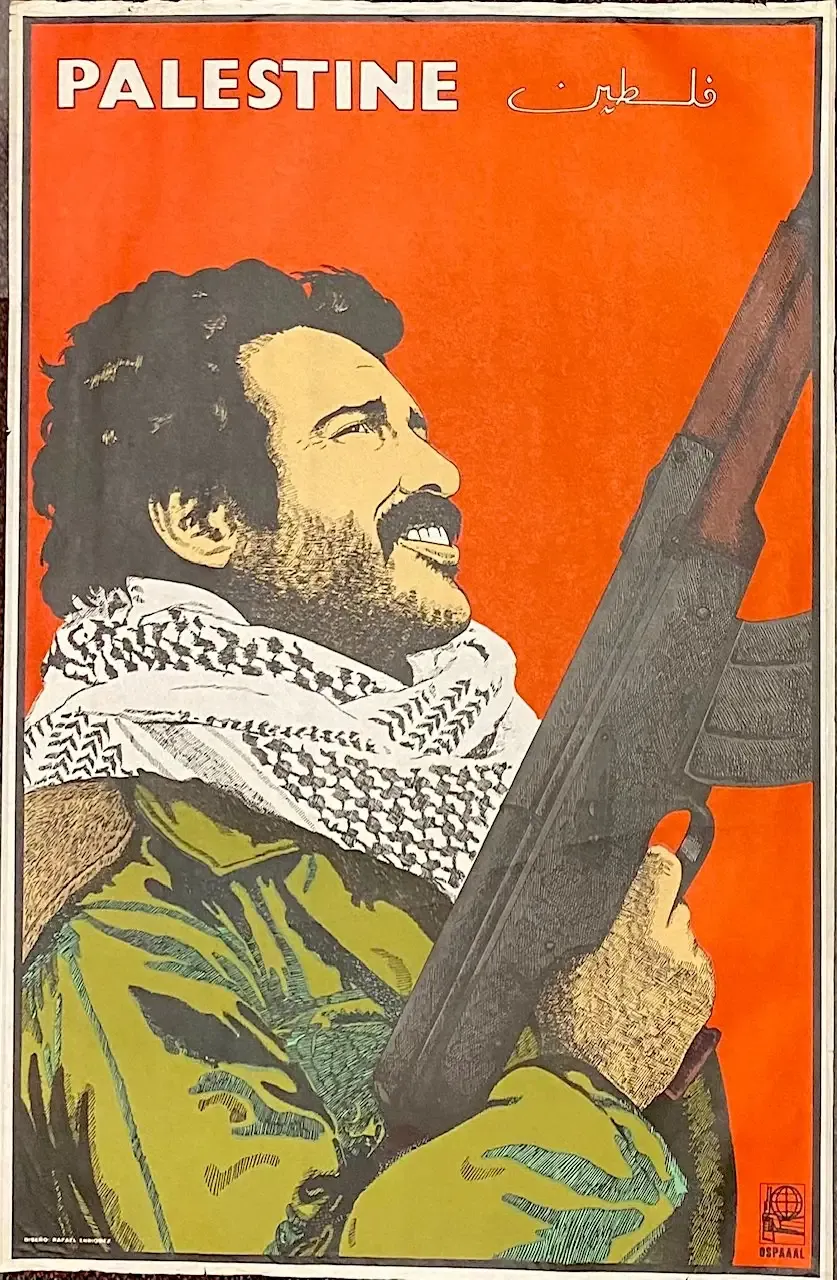

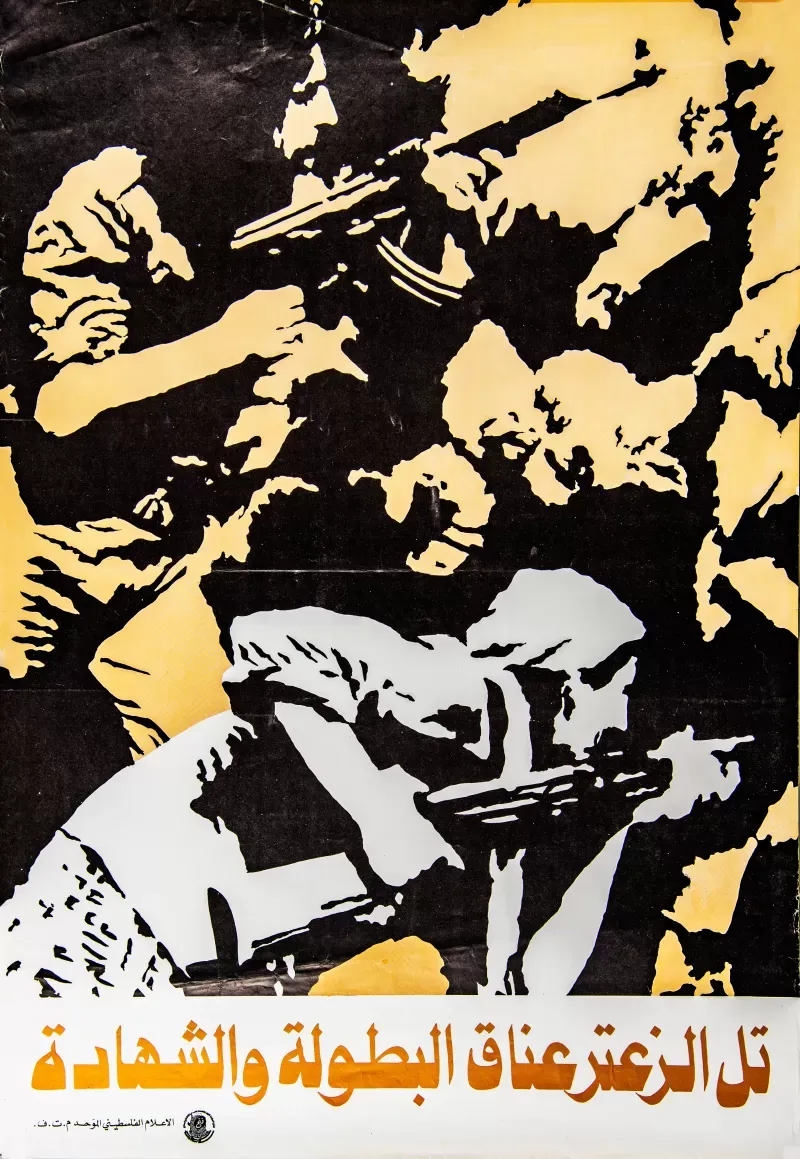

Stateless, dislocated, and dispersed, the Palestinians found comfort and a means of spreading the message within the prosaic poster. Depicting powerful symbols of hope, such as a dove or olive branch, or reflecting the call to arms, Palestinian posters form a testament to the resilience of a people drawn into a corner and forced to sustain their identity in alternate modalities of existence and creativity by harnessing the power of easily distributed prints.

Flourishing as a multicultural area in the first half of the 20th century, the Palestinian region under British rule manifested a vital artistic shift from religiously-dominated expressions of the late Ottoman era. Palestinian artists actively and eagerly contributed to the idea of modernity, developing painting practices, teaching/working studios, and cultural centers that reflected their authentic interpretations of Western influences. This intersection of cultures was dissected during the Arab-Israeli 1948 war when the British withdrew, terminating the mandate and allowing the State of Israel to form on grounds depleted of their former Palestinian residents.

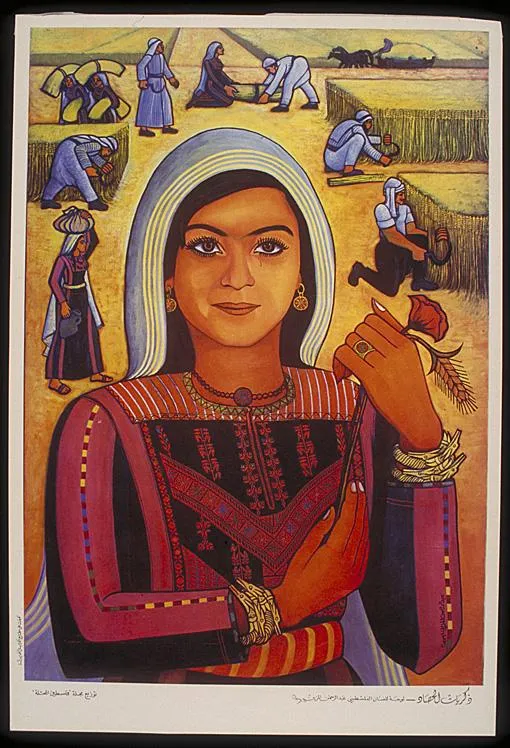

Forced to flee their home and dispersed in cities like Baghdad, Beirut, Damascus, Cairo, and Amman, as well as in the West Bank, Gaza, and Israel, once well-established artists of Jaffa, Haifa, and Jerusalem had to work tirelessly to rebuild their lives and careers, articulating their dislocated identity within and through their work. Although they appeared long before as an artistic expression, Palestinian prints overtook the role of paving the way for the future of Palestinian art and culture while it was threatened to be extinguished.

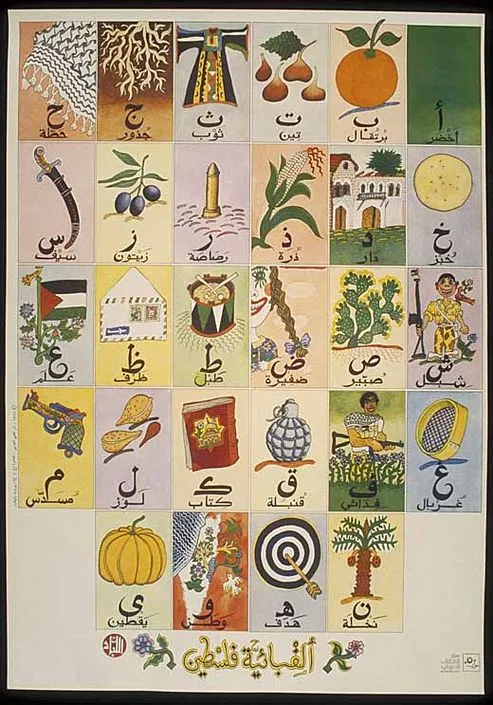

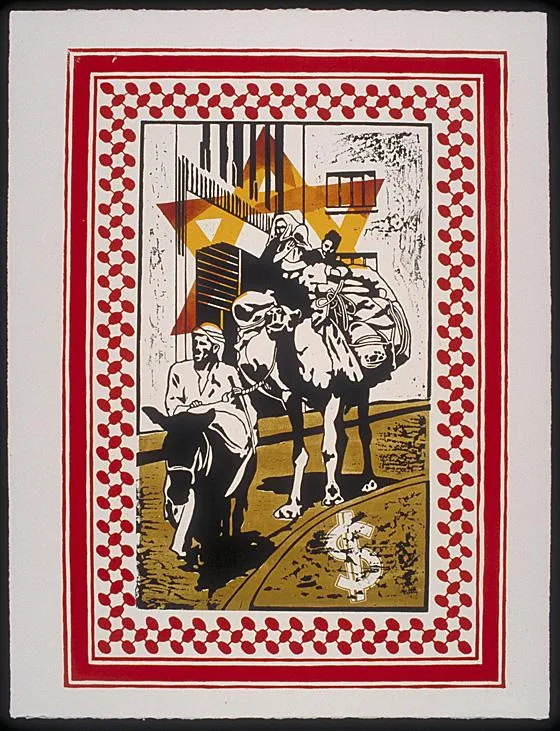

The Nakba of 1948, meaning the catastrophe in Arabic, meant the overtake of land and territory, coupled with absolute erasure of culture, heritage, and traditions, fabricating narratives of an area desolated and unpopulated. Although ephemeral in nature, the power of the poster as a visual empowering, emancipating tool emerged as an efficient instrument in sustaining, creating, and controlling the narratives. Propelled by the liberal movements of the 1960s, Palestinian posters became a means to retake and reclaim the stories, with artists discovering the emancipatory, empowering, and comforting properties of graphic prints.

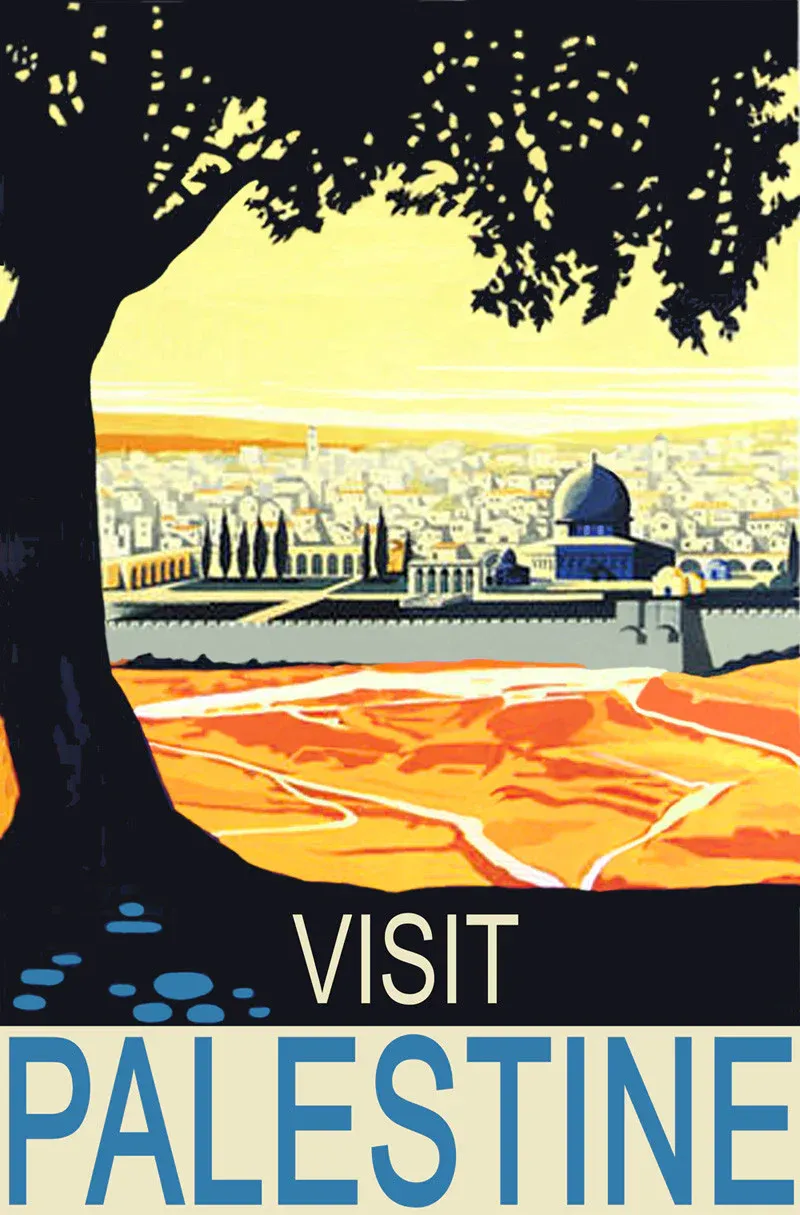

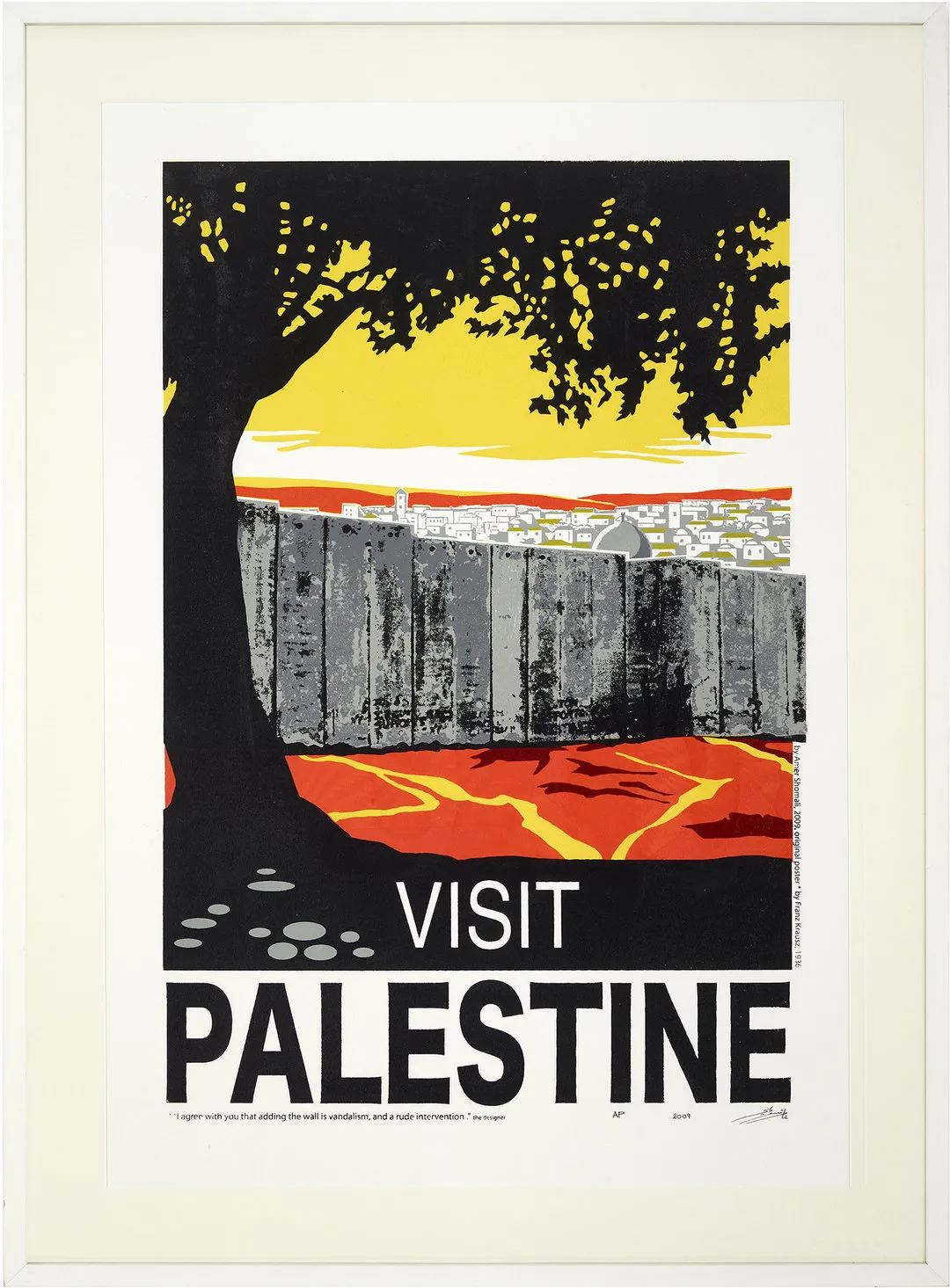

The infamous example of the poster design of the Austrian Jewish Franz Krausz, who emigrated from Germany to Palestine in the 1930s before the Holocaust, records the inclinations of the Zionist associations in Palestine and Israel to motivate people to "repopulate" the land. The idyllic commercial poster of Krausz's Visit Palestine from 1936, featuring a sun-drenched Al Aqsa in Jerusalem, permeated visual culture again in 1995 after David Tartakover reprinted the poster. Since then, the graphic print has been among the most reproduced, reprinted, and replicated designs, often remixed and alternated to provoke. The empowering capacities of the image are most evidently observed in Palestinian artist and designer Amer Shomali's reiteration of Visit Palestine (2009), remastering the work with slabs of wall obscuring the view of the city's landmarks.

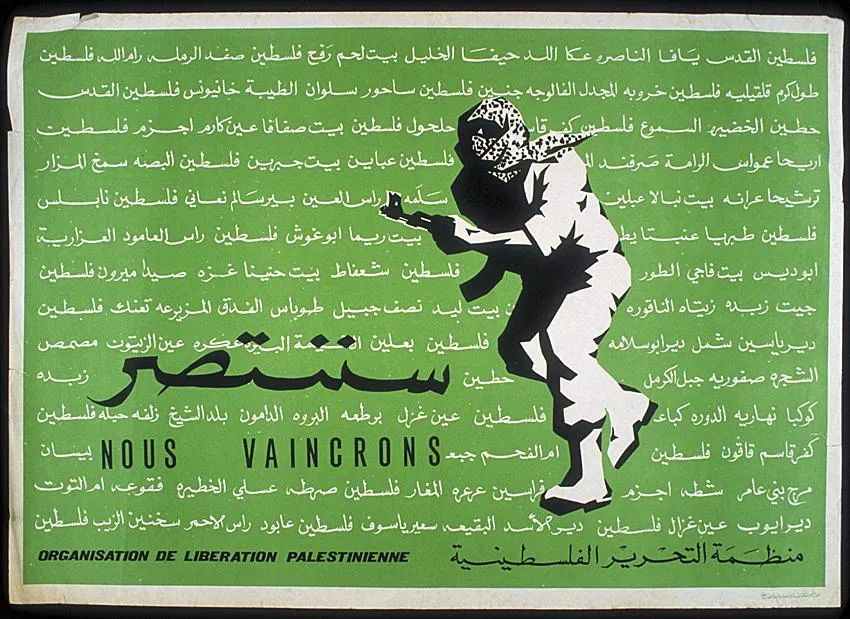

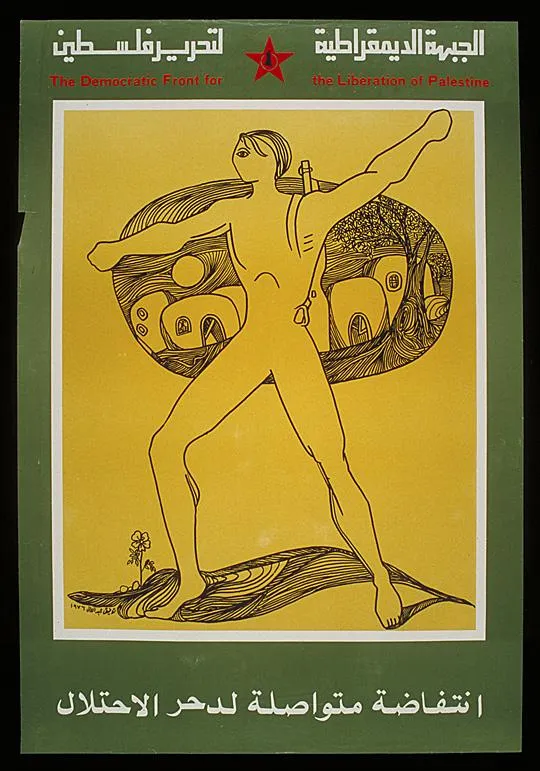

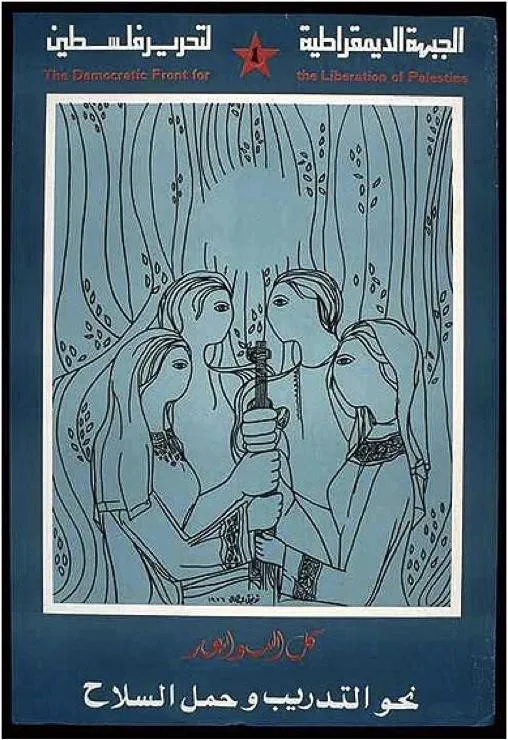

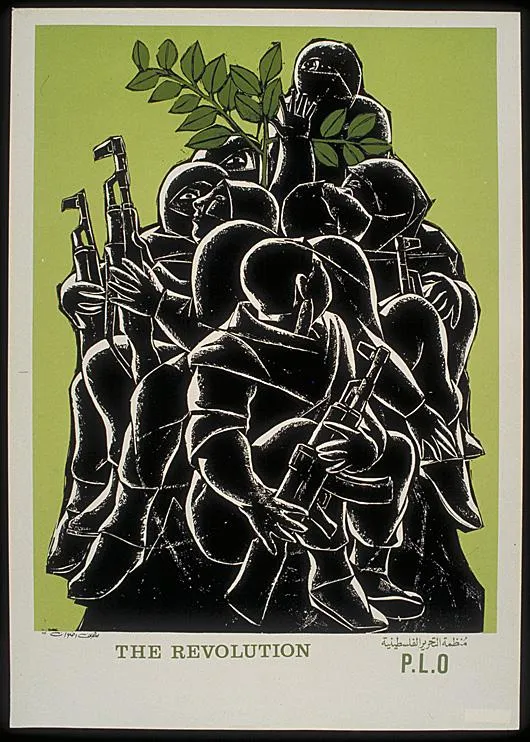

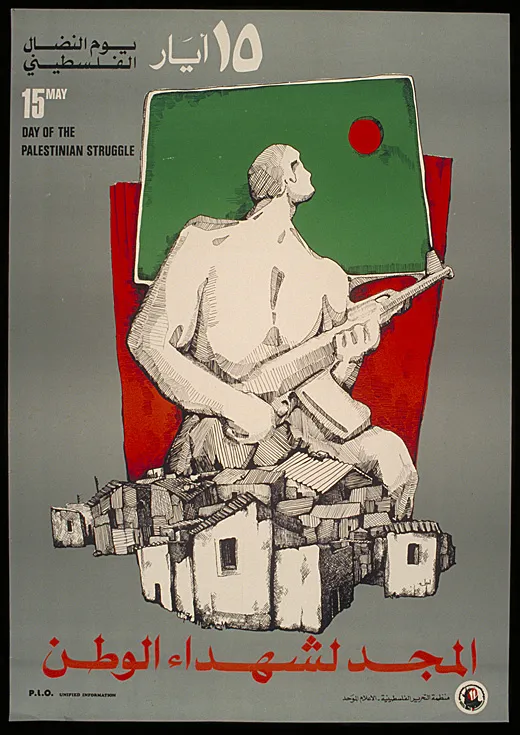

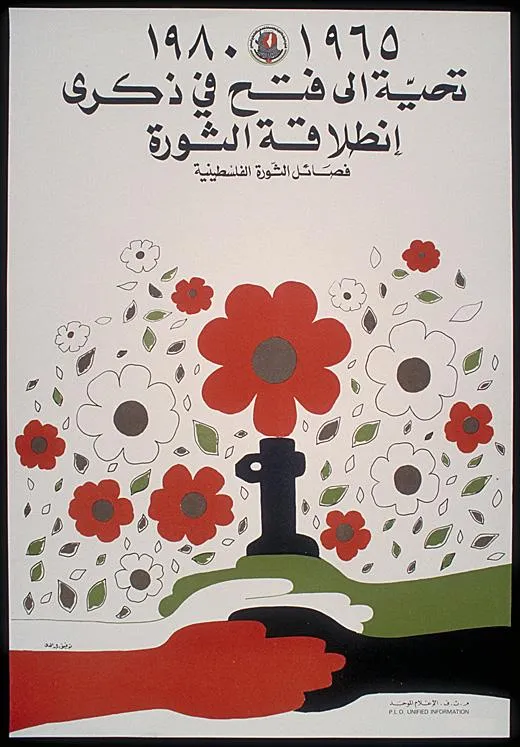

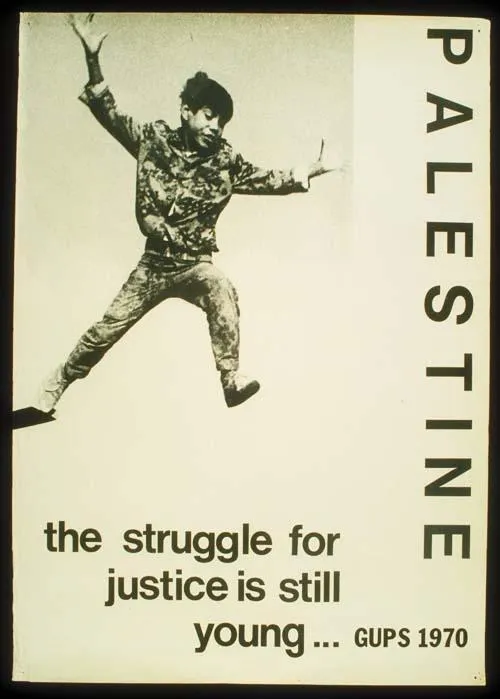

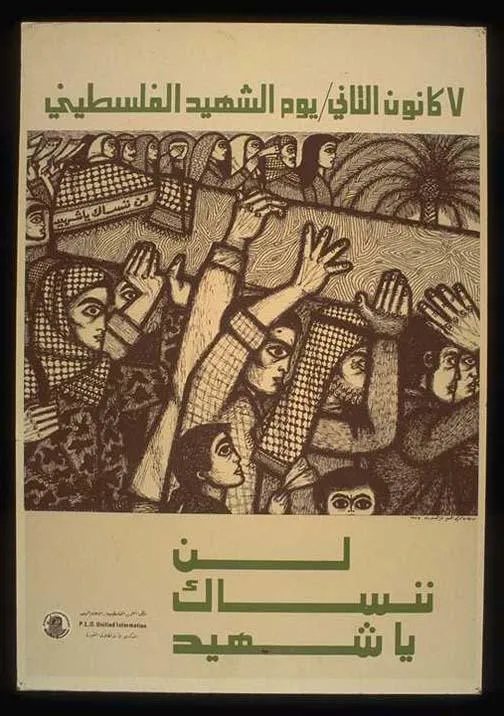

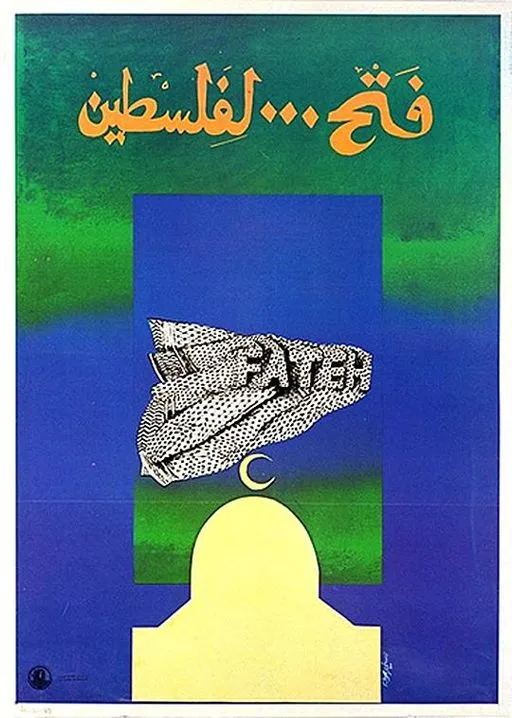

Although the seeds of revolution were planted as early as the 1950s, with aspirations of establishing a free and independent Palestinian state, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) was not set up until 1964. A year later, the PLO established the Department of Arts and National Culture with artist and art historian Ismail Shammout at its helm, with Beirut as their stronghold. The incentive in exile, thus, gained momentum, formulating a concentrated endeavor to utilize the power of the visual image within their cause.

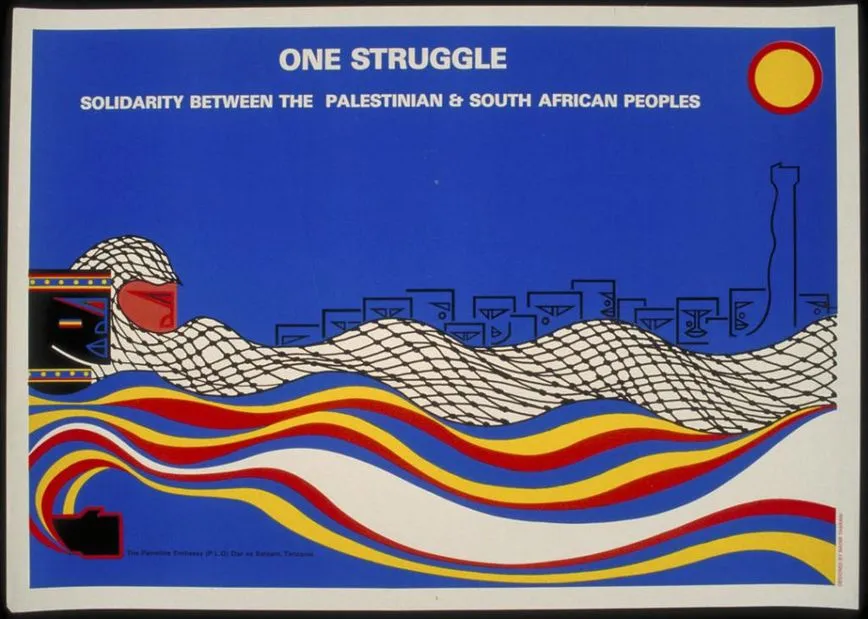

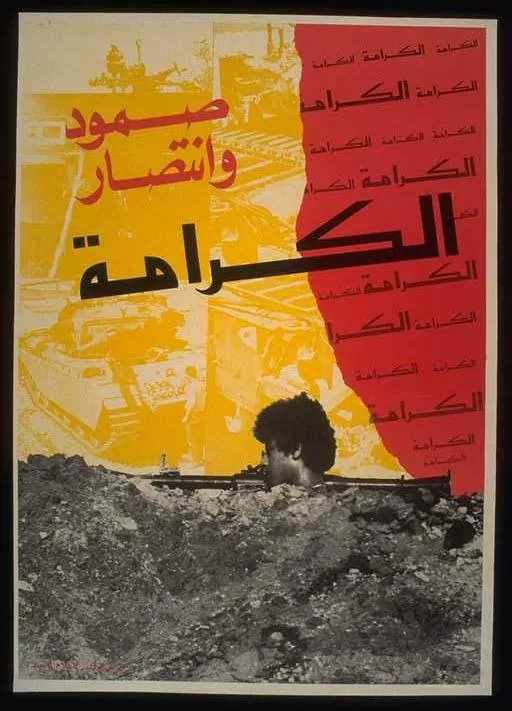

In Of Dreamers, Ezzeddine Qalaq and Palestine's Revolutionary Posters, Rasha Salti explains that the Palestinian revolution was perceived as "a profoundly transformative project," attracting "a nebula of dissident, gifted and innovative artists and intellectuals to Beirut."

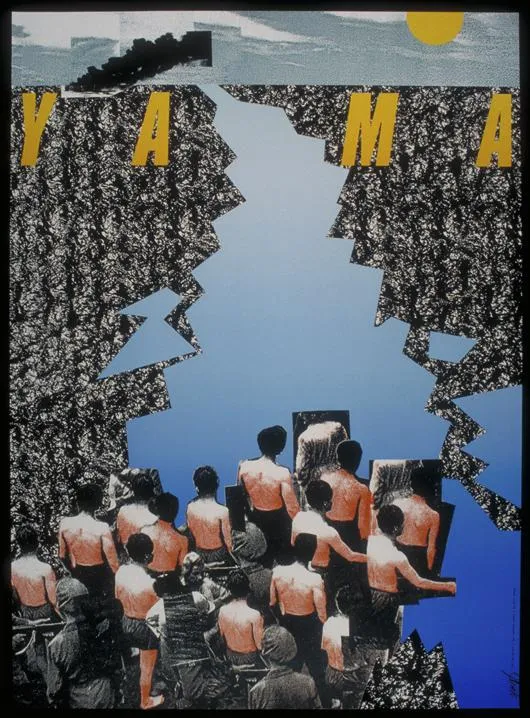

Artists and poets contributed to the production of posters. ... In their turn, artists discovered the institutional realm as well as the resources to innovate and experiment. ... The array of experimentation, diversity and creativity of Palestinian posters is bewildering. It has remained unprecedented in the Arab world, and remarkable on a worldwide scale.

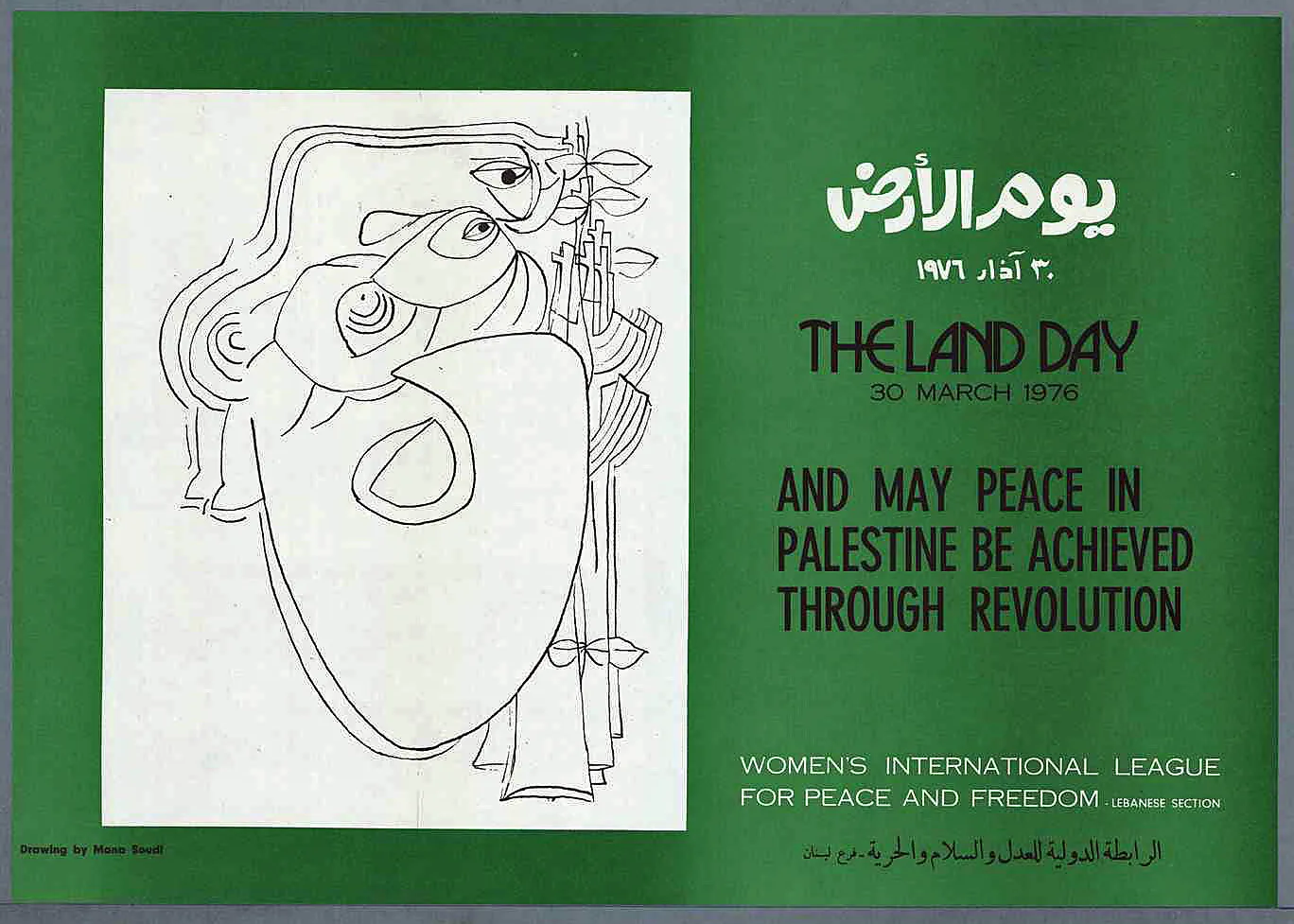

Leading artists such as Mona Saudi (b. 1945), Ghassan Kanafani (1936-1972), Sliman Mansour (b. 1947), Samir Salameh (1944-2018) Muaid al-Rawi, Rafic Charaf (1932-2003), and Mustafa al-Hallaj (1938-2002) joined the revolt, designing powerful graphics that conveyed the struggle for freedom and voiced their desires to return home. Formidable riffles were coupled with the keffiyeh, the traditional Palestinian headscarf, and impactful symbolism such as the dove, the olive branch, the horse, barbed wire, and folk elements integrated within the posters. From expressive to classical Arabic, the style of each print differed, focusing on finding ways to communicate with the people in, most often, richly-colored, simple, but powerful ways, superimposing the visuals with Arabic lettering, poetry, or political slogans.

As an instrument of mass communication, posters are marked by transience. Most often displayed on a wall of a public building, they are designed for a specific purpose to reflect an event and time, but they often continue to resonate beyond their original context. Thus, the incentive to preserve these invaluable documents of the Palestinian struggle has become precious — an act of cultural resistance and solidarity.

Institutional endeavors to defy the test of time include collections held at the American University of Beirut's Jafet Library, the International Institute of Social History, the Ethnographic and Art Museum at Birzeit University, the Center for the Study of Political Graphics in Los Angeles, and the Museum of Design in Zurich.

Publicly showcased, private collections such as those of Ezzeddine Qalaq, George Michel Al Ama, and Saleh Abdel Jawad's intifada poster archive also represent a bastion of hope in preserving the narrative of the Palestinian people. Among the most ambitious initiatives is the Palestine Poster Project Archives (PPPA), founded by Dan Walsh — a vast, open-source database preserving thousands of paper ephemera and digital images. The PPPA's digital collection now exceeds ten thousand entries, with over four thousand posters held physically.

In 2017, Walsh nominated Palestinian Posters for inclusion in UNESCO's Memory of the World register. The proposal was vetoed by the organization's Director, Irina Bokova — marking the first time a nomination was blocked in such a manner.

Alongside these archival efforts, the Artists Against Apartheid initiative has been instrumental in keeping the Palestinian cause alive through the visual arts. Over 6,000 posters have been submitted in solidarity with Palestine, highlighting the ongoing resistance and keeping the visual language of defiance and resilience in circulation worldwide. These posters are not just archived but actively used for outreach, pasted up in towns and cities, and shared as symbols of solidarity.

Today, under the imminent threat of erasure, preserving the narrative of the Palestinian people is not just a gesture of solidarity — it is an act of defiance, a moral imperative, and a commitment to memory. To collect, to archive, to circulate takes on an urgent form of resistance. In the face of violence and historical denial, to preserve is to persevere.