Hylozoic/Desires. Image courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation

Hylozoic/Desires. Image courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation As the doors of Sharjah Biennial 16 closed, the questions it posed refuse to settle. Titled to carry, this edition moved with deliberate slowness through histories, geographies, and political intensities, resisting spectacle in favor of sustained attention.

Curated by a five‑person team—Alia Swastika, Amal Khalaf, Megan Tamati-Quennell, Natasha Ginwala and Zeynep Öz—to carry rejected the monocular logic of the blockbuster in favour of what the curators called a 'para-cartography': a map drawn by many hands, across many tempos. Over four months, more than 150 artists, archives, collectives and sound projects braided Indigenous cosmologies, feminist lifeworlds, and post‑extractivist critique into a roaming, polyphonic exhibition across Sharjah and beyond.

The urgency felt palpable. While wars, climate collapse and far-right retrenchment dominate today's headlines, to carry insisted on kinship and co‑learning as forms of resistance. Rather than parcel out space discipline‑by‑discipline, the curatorial quintet wove their lines together, letting a Ghanaian step‑well echo next to a Filipino pearl‑market, or a Gaza darkroom converse with a Delhi graveyard.

We sang, we rejoiced, gazing at the sky adorned with a thousand stars. Together, we stood. No matter how heavy the trials, we will keep guarding this land. This land is our bone, and the water is our blood.

— Mama Deci, one of the leaders of the Indigenous community in Kapan, Indonesia

What do we carry when we migrate, mourn or simply survive? As this "open‑ended proposition" recedes, ten standout works, reviewed below, show how artists metabolised the curators' prompt: turning sound, salt, shells and orphaned newsreels into tools for way‑finding amid precarity.

In a time when even "green" futures are too often built on sacrifice zones, to carry proposes the Biennial as a threshold space: part vigil, part laboratory, part gathering well. Here, artistic practice doubles as collective cartography—charting not the fixity of borders, but the moving solidarities we will need to navigate what comes next. The exhibition may be over, but its call to shoulder history—tenderly, defiantly, collectively—remains.

we are carried.

In bellies. In arms.

In love. In hope.

In caskets. In urns.

In grief. In memories.

Our whole lives

And into the next

We are carried

— We Are Carried by Sara Rian

Bathed in red light, two monumental murex seashells hang mid-air in Monira Al Qadiri's Gastromancer (2023), inviting viewers to press their ears against their glossy cavities. Instead of ocean waves, we hear an eerie, tender dialogue between the shells as they recount their transformation—from female to male—triggered by tributyltin (TBT), a red biocide used on oil tankers.

This real phenomenon, first documented by scientists in 1981, showed that TBT disrupts hormonal systems in marine mollusks, erasing reproductive functions and collapsing populations. Al Qadiri draws on this unsettling science and blends it with speculative fiction, referencing The Diesel (1994) by Emirati author Thani Al-Suwaidi, a novel exploring gender and identity in the wake of the Gulf's oil boom.

By animating these shells as narrators, the work probes how extractive industries don't just pollute ecosystems—they transform bodies, futures, and the very fabric of being.

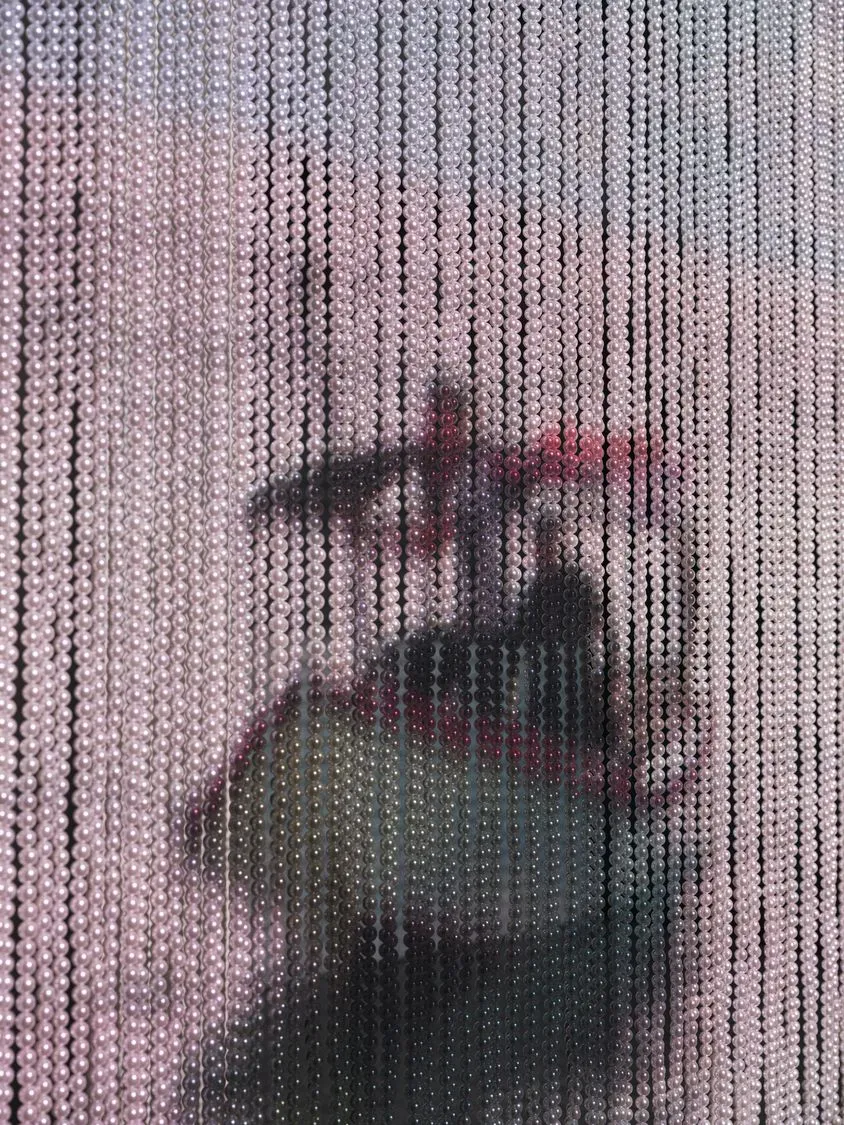

Stephanie Comilang's Search for Life II (2025) turns one of the the Sharjah Art Foundations's galleries into a tidal zone where history, commerce and sci‑fi speculation wash over one another. Two video streams face each other. One is projected onto a gleaming curtain of thousands of pearl beads; the other onto a conventional screen framed by a tiered wooden pier that echoes the rise‑and‑fall rhythm of traditional Gulf pearl diving.

The first channel drifts through archival fragments and present‑day footage from the Arabian Gulf and the Philippines—boats slipping out at dawn, divers resurfacing with lungs ablaze, songs that once synchronized communal labour. The second scrolls like an endless feed: Chinese livestreams hawking cultured pearls, TikTok tutorials on spotting fakes, manicured hands flaunting gem‑encrusted nail art. Together they chart the pearl's metamorphosis from rare ocean treasure to mass‑market click‑bait, exposing the hidden labour and ecological toll behind its lustre.

Comilang calls her method a "science‑fiction documentary," and the label fits. By collapsing eras and viewpoints, she lets the pearls themselves seem to narrate—glimmering witnesses to extraction, migration and the digital afterlives of desire.

The Hedge of Halomancy (2025) by Hylozoic/Desires, the multimedia duo of Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser, unfolds a mesmerizing journey through lost colonial histories and speculative futures. Centered on the vanished Great Hedge of India—a sprawling 4,000-kilometer barrier planted by the British Empire to enforce a deadly salt tax—the film installation blends historical fact with poetic fiction. At its core is Mayalee, a defiant courtesan who uses salt divination, or halomancy, to disrupt imperial control and weave a secret network of resistance.

Presented within a salt-encrusted frame, the 23-minute film visualizes the hedge as both a physical and metaphorical border—porous, fraying, and alive. Termites consume the hedge as colonial power crumbles, while Mayalee's prophecies unsettle the hedge's commissioner, Allan Octavian Hume, whose gradual disillusionment parallels the empire's unraveling. The installation evokes a world where vegetal borders and indigenous knowledge pulse with subversion, bridging the material and spiritual.

A survivor of the Armenian genocide, Kegham Djeghalian Sr (1915–1981) founded Gaza's first professional photography studio, Photo Kegham, in 1944. For nearly four decades, he documented everyday life in the city—portraits, family gatherings, and official events—quietly building a visual memory of Gaza in the mid-twentieth century.

In Photo Kegham of Gaza: Unboxing (2020–2024), his grandson, artist and educator Kegham Djeghalian Jr, reactivates this legacy through a poetic and critical gesture. After discovering three red boxes filled with negatives and keepsakes in his father's Cairo home, Djeghalian Jr embarked on a research journey shaped by the gaps and silences in the archive. Organised into four themes, the project forgoes captions and chronology to foreground an 'unmade archive'—one that resists fixed historical readings and instead invites reflection on disrupted lineages and the fragility of memory.

Pallavi Paul's How Love Moves (2023) is a quiet epic of mourning, care, and resistance. Set in Delhi Gate Cemetery, the 63-minute film unfolds across five chapters named after Islamic prayer times—marking the rhythm of a day, a breath, and a life. At its centre is Shamim Khan, a gravekeeper whose daily rituals of tending to the dead offer dignity amid devastation.

Through Khan's perspective, Paul weaves together fragments of personal loss, state violence, and ecological collapse—from the Delhi Riots to mass COVID-19 burials. Official records, whispered stories, and lyrical interludes build a cinematic tapestry of grief that refuses closure. The narrative resists linearity, instead embracing a kind of devotional montage where mourning becomes both political and planetary.

Rendered with tenderness and urgency, How Love Moves is less a documentary than an amulet—mourning what's lost while safeguarding the sacred in the everyday. Paul shows that love, even when fractured by borders and death, still moves: through breath, through soil, through care.

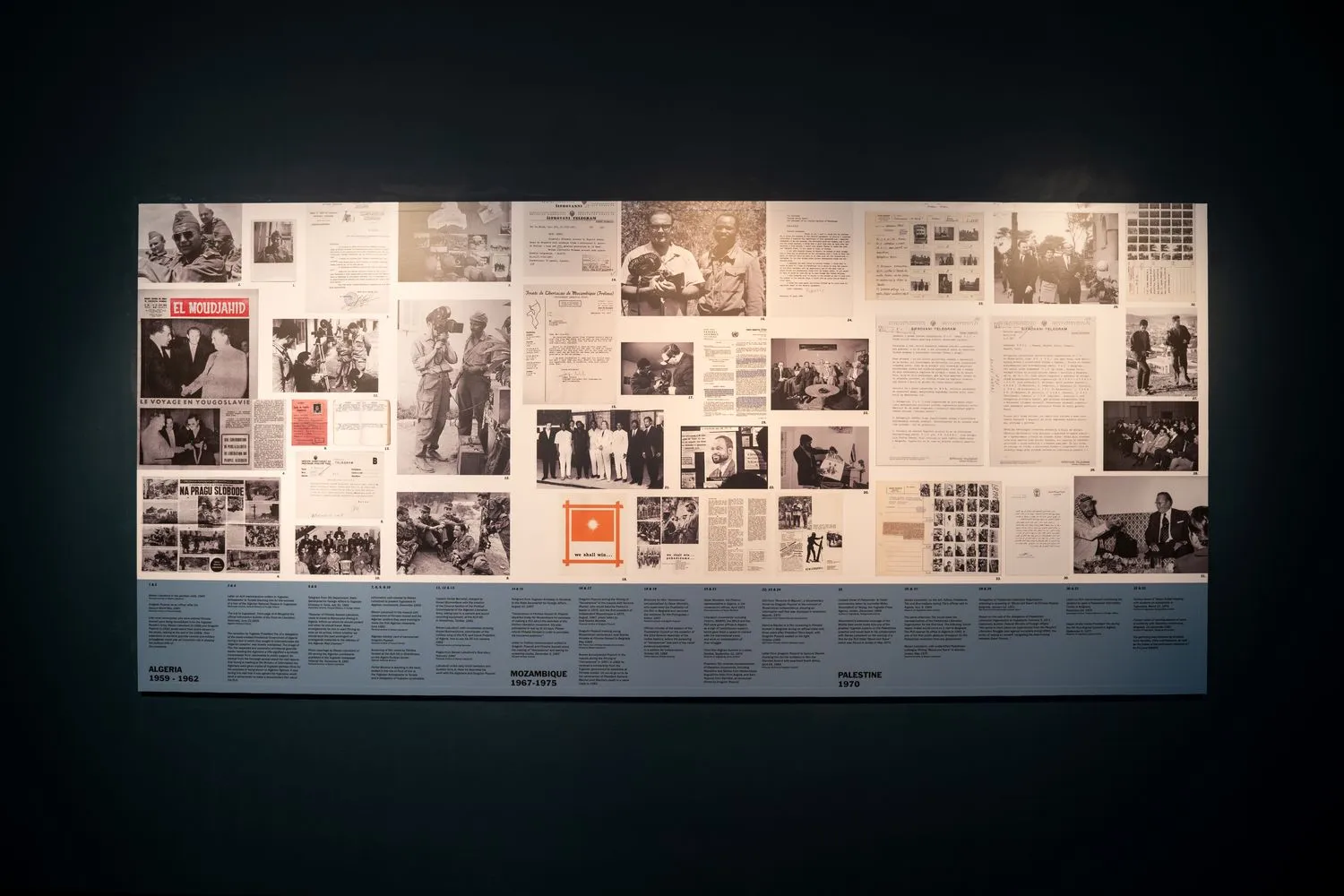

Since 2016, filmmaker and archive artivist Mila Turajlić has been digitizing forgotten reels from the Yugoslav Newsreels agency, unearthing a vast visual record of the Non-Aligned Movement's cinematic solidarity with decolonizing nations. Shot without sound by cameramen Stevan Labudović and Dragutin Popović, these images—capturing struggles in Algeria, Palestine, and Mozambique—were filmed as acts of internationalist support, yet languished for decades in the vaults of Filmske novosti, unindexed and unseen.

With Non-Aligned Newsreels: Voices from the Debris, Turajlić reanimates this material through public workshop series held in countries and diasporas linked to the 1961 Belgrade Conference, where communities reencounter the footage and narrate it aloud, layering it with personal and political memory. These gatherings create a living archive, transmitting South-South solidarities across generations. These sessions become spaces of shared reckoning, where histories of resistance are reclaimed and passed on—not as fixed narratives, but as living inheritances.

Rather than treating the footage as static documentation, Turajlić reframes the archive as a porous, political space: one where solidarity can be remapped, and where fragments from a fractured internationalism might offer tools for imagining decolonial futures still to come.

Amid the dim light of the Old Al Jubail Vegetable Market, Aziz Hazara's multichannel installation I Love Bagram (ILB) (2025) unfolds like an understated reckoning, offering a quietly searing reflection on the aftermath of foreign military occupation in Afghanistan. Working with photography, sculpture, video, and sound, Hazara assembles a counter-archive of everyday debris left behind at Bagram Airfield—a site first militarised by the Soviets, later expanded by NATO, and abruptly evacuated by U.S. forces in 2021. Flatscreens rest on battered crates, looping footage that speaks to what endures after the soldiers have gone: scattered consumer goods, discarded tools, and charred documents reveal the material imprint of decades-long imperial entanglement.

In MoonSighting (2024) and Skin Care (2024), Hazara turns to photography, capturing fragments of daily life and black-market leakage that seep through imperial cracks. With sharp irony, he reportedly ships some of Bagram's leftover trash back to the U.S.—a quiet act of poetic justice. Beneath the project's restrained aesthetic lies a deep moral indictment of war, aid, and profiteering, countered by gestures of play, resistance, and kinship. Hazara doesn't just show what was left behind—he asks who must live with it.

Far from being a static archive, Singing Wells moves to the rhythm of memory. Born from a collaboration between Nairobi's Ketebul Music and London's Abubilla Music, this living project has spent over a decade tracing the sonic lifelines of East Africa—recording, archiving, and amplifying the musical traditions that pulse across Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Mozambique and South Africa. Built as a roaming studio, Singing Wells travels with its ears open, forging moments of encounter rather than extraction. Musicians, storytellers, and multi-instrumentalists shape the archive as co-authors, their performances echoing with celebration and lament, lineage and improvisation.

At Sharjah Biennial 16, Singing Wells is transformed into an acoustic gathering. The exhibition space hums with voices and rhythms—taarab music carried across the Swahili coast to the Arabian Gulf, the plucked resonance of the nyatiti, and the testimonies of families who have kept songs alive across generations. Assembled by project co-founder Tabu Osusa and researcher Helena Wheatley, this first-ever listening space doesn't simply document the past—it vibrates with the urgency of continuation, offering a resonant reminder that heritage is not what we preserve in silence, but what we dare to keep singing.

Suzanne Lacy's landmark works blend performance, politics, and collective ritual to confront entrenched social narratives. In In Mourning and In Rage (1977), created with Leslie Labowitz, grief becomes protest. Staged on the steps of Los Angeles City Hall and broadcast across local media, the performance challenged the sensationalism surrounding a series of murders, demanding public attention to the systemic roots of gender-based violence.

The Crystal Quilt (1987) reframed cultural perceptions of ageing through a striking live tableau: 430 older women seated at patterned tables in a quiet, coordinated act of visibility and dignity. Decades later, The Circle and the Square (2017) echoed this commitment to community—bringing together Muslim and non-Muslim residents of a post-industrial English town in a shared act of song. Sacred Harp hymns and Islamic vocal traditions intertwine in a two-channel video that captures not only harmony, but healing.

Concrete Thread Repertoire is less an artwork than a living, breathing archive of Indonesia's resistance cultures—woven together by artists, researchers, and grassroots communities across the archipelago. Presented as a collaborative installation, the project maps out what scholar Melanie Budianta terms "emergency activism": urgent, often improvised civilian responses to state and corporate violence. From post-1998 reformasi movements to the century-old anti-capitalist Samin resistance, it brings together a constellation of case studies unified by the material and poetic tactics of everyday struggle.

Through documents, motifs, and objects—some natural, others fabricated—the archive traces how resistance is enacted, remembered, and shared. It is grounded in situated knowledge: not only through institutional reflection but through the voices of Komunitas Wadas, Mothers of Mollo, and other frontline communities. Their stories, songs, and artefacts are threaded into the work as forms of collective authorship and care.

Rejecting the abstraction of political theory, Concrete Thread Repertoire foregrounds tangible, embodied strategies for solidarity and survival. It's a project that insists archives are not just about the past—they are tools for imagining a more just and grounded future.