David Goldblatt, A Pensioner with the child of a servant. Wheatlands, Randfontein, Transvaal. (Gauteng), September 1962. Courtesy of Jean Bigue

David Goldblatt, A Pensioner with the child of a servant. Wheatlands, Randfontein, Transvaal. (Gauteng), September 1962. Courtesy of Jean Bigue The famous South African poet Mongane Wally Serote wrote about the importance of creativity for survival. "There is an intense need for self-expression among the oppressed in our country," he noted. "We neglect the creativity that has made the people able to survive extreme exploitation and oppression. People have survived extreme racism. It means our people have been creative about their lives."

Photographers in South Africa who suffered under the apartheid system—enforced by the white minority and prescribing strict racial segregation in all spheres of life—used photography as a creative tool to document their daily realities and those of their Black communities. From picket lines to mundane everyday topics, South African photography presents a visual archive of a country built on the exploitation of the majority and the extreme racial violence it continues to grapple with.

Amongst the horrors, humanity prevails. Images that documented atrocities and brutalities of the apartheid, followed by those made by the 'born-free- generation that re-examine racial categorization and identity, societal tropes, memory, and tradition, became resonant over and beyond the national borders as symbols of resistance to oppressive regimes and the struggle for equality, inclusion, social justice, and cultural expression. They also offer hope and belief that struggle can bring change and that the sacrifice of many is not in vain.

In the present circumstances of the ongoing genocides around the world, South African photography gains new currency and meaning, prompting a reflection on our shared global history, and revealing that through acceptance, reconciliation, and understanding, a different future is possible.

One of the photos that captured the horrors of the apartheid regime is Sam Nzima's The Soweto Uprising (1976), listed by Time Magazine in 100 influential images of our time. The protest erupted in the Soweto township after Afrikaans was introduced in black schools as the language of instruction. Led by Black school children, the uprising was brutally suppressed, leaving hundreds of children dead. Nzima's photograph shows Mbuyisa Makhubu, a fellow student, carrying the body of Hector Pieterson, who was just 12 years old at the time, with Pieterson's sister, Antoinette, next to him. It was widely circulated both domestically and internationally, becoming an iconic image of the anti-apartheid struggle that rallied oppositional voices and helped dismantle the system.

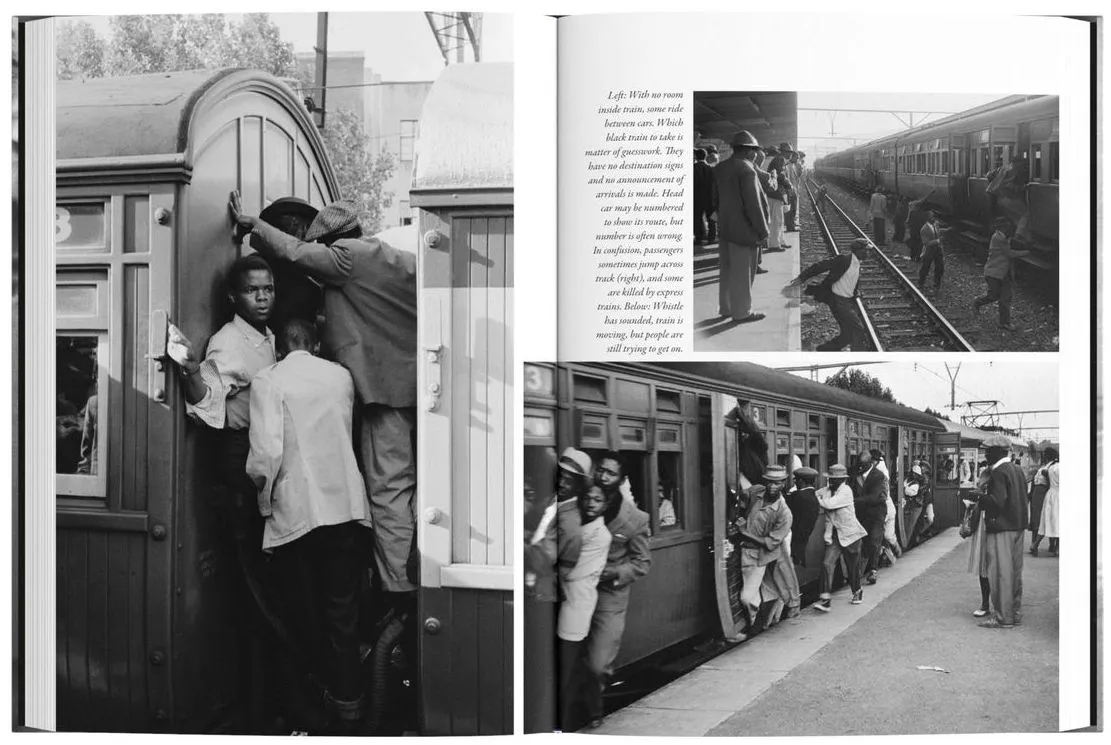

Working alongside Nzima—and often risking their lives to capture the truth—were also David Goldblatt, Ernest Cole, and Peter Magubane. Instead of going to picket lines, Goldblatt engaged with politics more subtly, exposing the dynamics of discrimination through everyday shots. Commenting on the new reality of South Africa after apartheid, he criticized the persistence of racial inequalities. "Apartheid has gone, its half-life will continue beyond knowing." Similarly focused on the everyday is the work of Ernest Cole, who had to smuggle negatives for his House of Bondage book out of South Africa in order to publish it.

Official photographer of Nelson Mandela, Peter Magubane, followed the protests and captured some of the most disturbing images of the apartheid, including the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 when police opened fire on protestors, killing 69 people. He often carried his camera in loaves of bread, hollowed-out Bibles, or milk cartoons to avoid the police. "I did not want to leave the country to find another life. I was going to stay and fight with my camera as my gun," he said in 2015. "I did not want to kill anyone, though. I wanted to kill apartheid."

Following long decades of struggles and suffering, the oppressed people of South Africa finally defeated the regime of racial segregation in 1994, when the first democratic government led by Nelson Mandela was established. The shift in social organizing brought with it the urge to examine one's identity, as well as to document new, democratic changes that were happening.

Photographers were once again at the forefront of the events, using their cameras more freely to capture the transition, liberated from the urgency to witness the injustices. New themes seeped into the repertoire, including examinations of national and personal identities, memory, spirituality, and social issues. The work of Zanele Muholi comprises arresting portraits of the LGBTQ+ community that aim to remove negativity attached to queer identity, as well as "re-write a black queer and trans visual history of South Africa for the world to know of our resistance and existence at the height of hate crimes in SA and beyond." Santu Mofokeng, another 'visual activist' who shaped South African photography, arrested attention with his body of work that addressed weighty subjects with a poetic style featuring different diaphanous materials, such as smoke or mist. "I was less interested in 'unrest' than in ordinary township life," he once explained, which is evident in the themes that preoccupied him, such as memory, spirituality (Train Church series), and the trope of land in the Black community.

However, the apartheid and post-apartheid do not mark a simple dichotomy. The continuity of unsolved conflicts, poverty, the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and other social issues signaled to artists that while the epoch of 'heroic documentary,' in the influential art critic and curator Okwui Enwezor's terms, may be over—an epoch when artists often risked their lives to document injustices—the issues of human suffering and brutality were continuing and needed to be addressed anew.

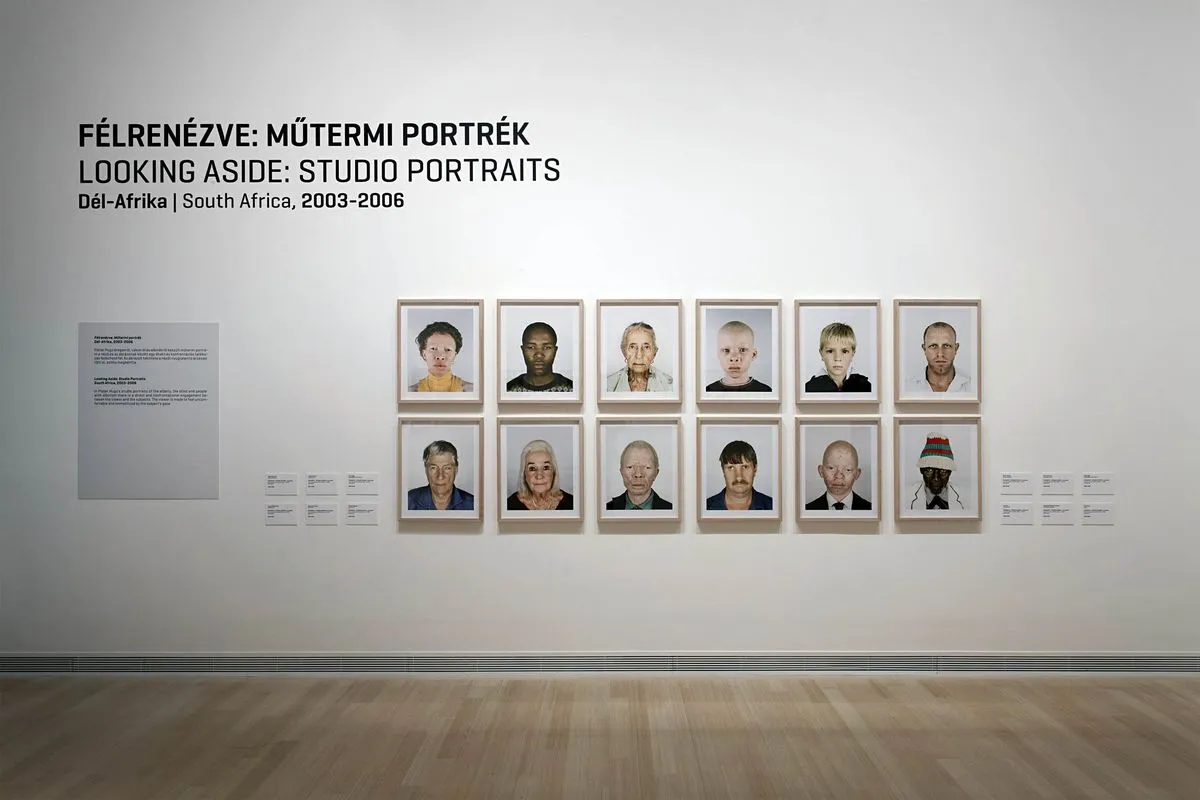

Pieter Hugo thus dedicated his time to documenting marginalized groups, going beyond the state borders to photograph the effects of colonization, exploitation, and globalization across the African continent, including children who survived the Rwandan genocide and technology dumpsites in Ghana. In his celebrated series Looking Aside (2004-2005), he focused on people with albinism, combining the aesthetic of ID photos with a strong political statement on the new visual language South Africa was adopting, exclusionary in new ways. "All South Africans were required to carry a photo ID," he explained. "My series turns this loaded compositional style on its head to document people marginalized by the glib visual propaganda of the 'new', liberated South Africa."

Exploring cultural identities and injustices is also the work of Jodi Bieber, who received the World Press Photo of the Year award in 2011 for the portrait of Bibi Aisha, an Afghan woman whose face was mutilated by her husband and brother-in-law. Her Real Beauty project addressed the advertising culture that promotes Western ideals of beauty in SA and issues of body identity and self-image.

The complex post-apartheid period riddled with various problems and the culture of violence also drew a new generation of artists born 'free' to take cameras and continue documenting the South African reality. Among them is Lindokuhle Sobekwa (b.1995), whose images show the effects of drug epidemic but also explore his personal story, and Sydelle Willow Smith, who, as a white South African, is engaged in revealing "the intimacies of class and race that continue to define South Africa's hopes."

"I have been told that I am a child of the "rainbow nation," that the advent of democracy means that racial differences would cease to exist. Yet it's clear that our relationships in this country remain largely mediated – affected, limited, constrained, corroded, delineated – by race," she said in a 2019 interview for Huck magazine.

Besides being of documentary relevance, photography in South Africa was also used to examine entrenched identity politics rife with colonial references and epistemologies. In 2013, Santu Mofokeng published The Black Photo Album/Look at Me: 1890-1950, made of digitally retouched studio photography showing Black working- and middle-class families he had collected over the years. Aesthetically fitting into Victorian photographic discourse, the photos raise questions about intention—were they taken to counter epistemic violence of social Darwinism that put Black people in natural history books, or were they a symptom of 'mental colonization'? Enwezor wages in on this by saying that they provide "an ethical sense of African agency" and are symptomatic of Black people's resistance to colonial violence and marginalization.

"In particular, the use of dandy and sailor style clothing and the choice of Scottish dress are perceived as a subversive, performative strategy of appropriation, which contributed to the production of visual counter-knowledge, to subject formation and individual agencies within the Black community," explains art historian Elisaveta Dvorakk.

Mogokeng's powerful address of the issue through The Black Photo is one of the examples of artists reclaiming their heritage and taking over the narrative by rejecting the colonial, Western gaze and stereotypes. From the younger generation of South African photographers, the work of Lebohang Kganye stands out for its inventive use of memory and fantasy to explore personal and collective identity. Thabiso Sekgala (1981-2014), another artist from the 'born-free' generation, turned to his neighbors and land in KwaNdebele—a settlement established for Black people forced out of urban areas by apartheid government—to show the psychological effects of forceful displacement, migration, and resettlement. The portraits he took, showing sympathy and understanding, speak of lost hopes, the deep complexities of recovering individuals and society, and the enduring racism and inequality. "Images capture our history, who we are, our presence and absence," he noted.

Confronting the past and current machinations of political elites of the Rainbow Nation, South African photography has made significant contributions to global narratives on race, gender, culture, and politics. Dealing with local circumstances, it beacons the universal themes of social justice and freedom that resonate with audiences worldwide, and also investigates the black subject, replacing the prevailing stereotypical image with a more sympathetic one. In doing so, it unsettled the apparatuses of power, allowing for a complex, heterogeneous image to emerge.