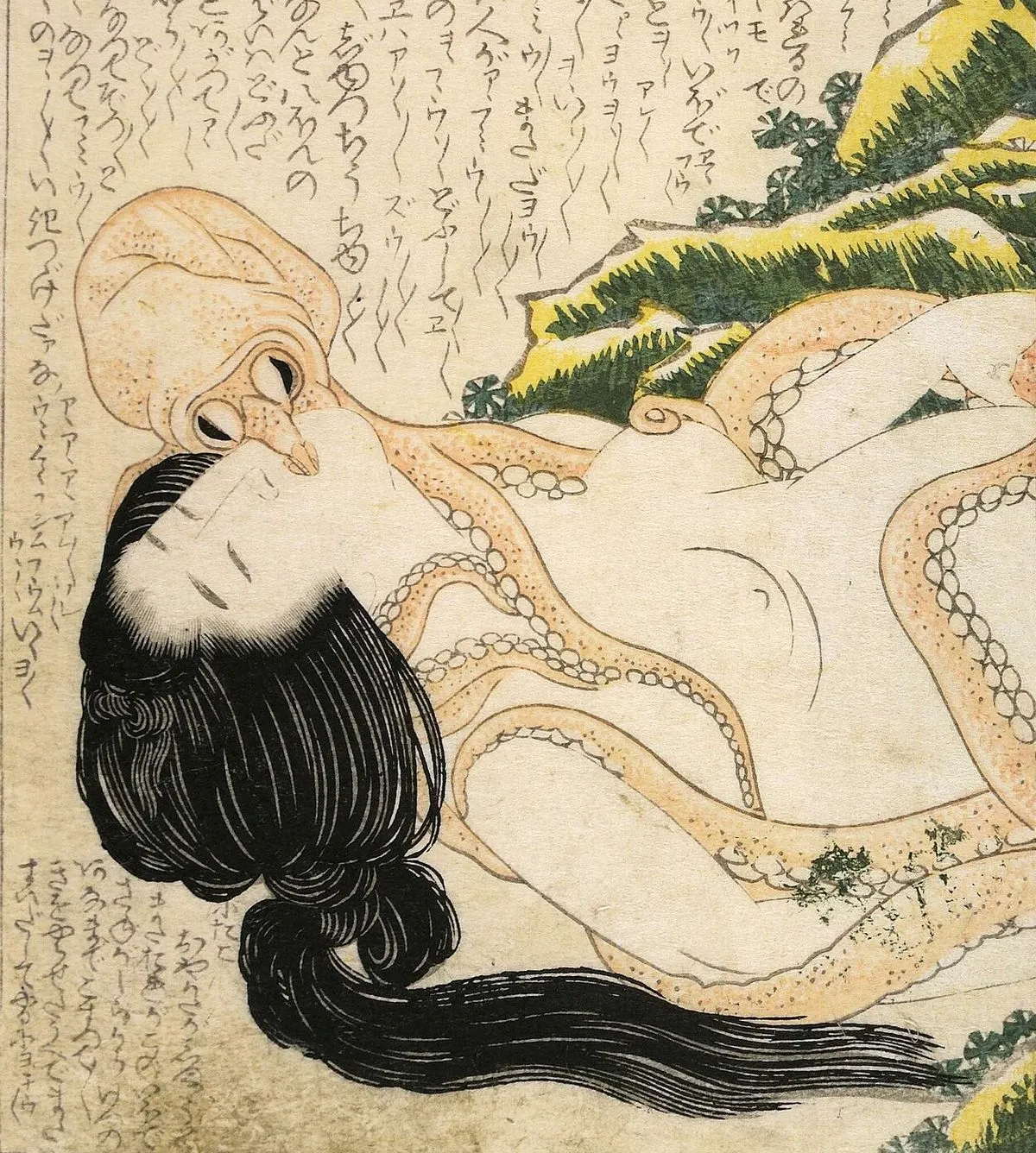

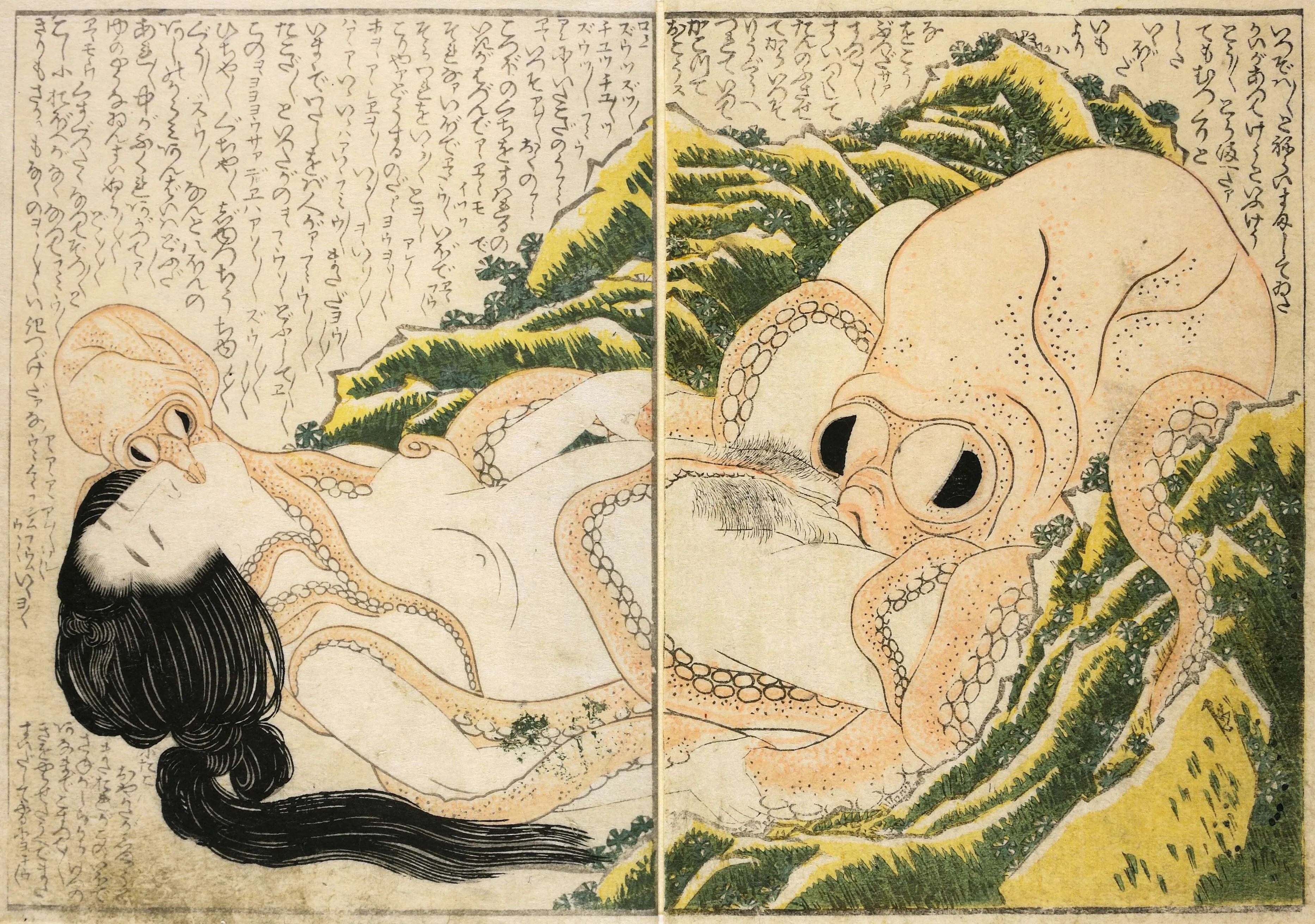

Hokusai, The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife (detail), 1814. Creative Commons

Hokusai, The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife (detail), 1814. Creative Commons The artist who created one of the most iconic images in the history of art, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, 1831, showing sailors fighting a huge wave with mount Fuji looming in the background, is also behind some of the more controversial works of Japanese erotic art called shunga.

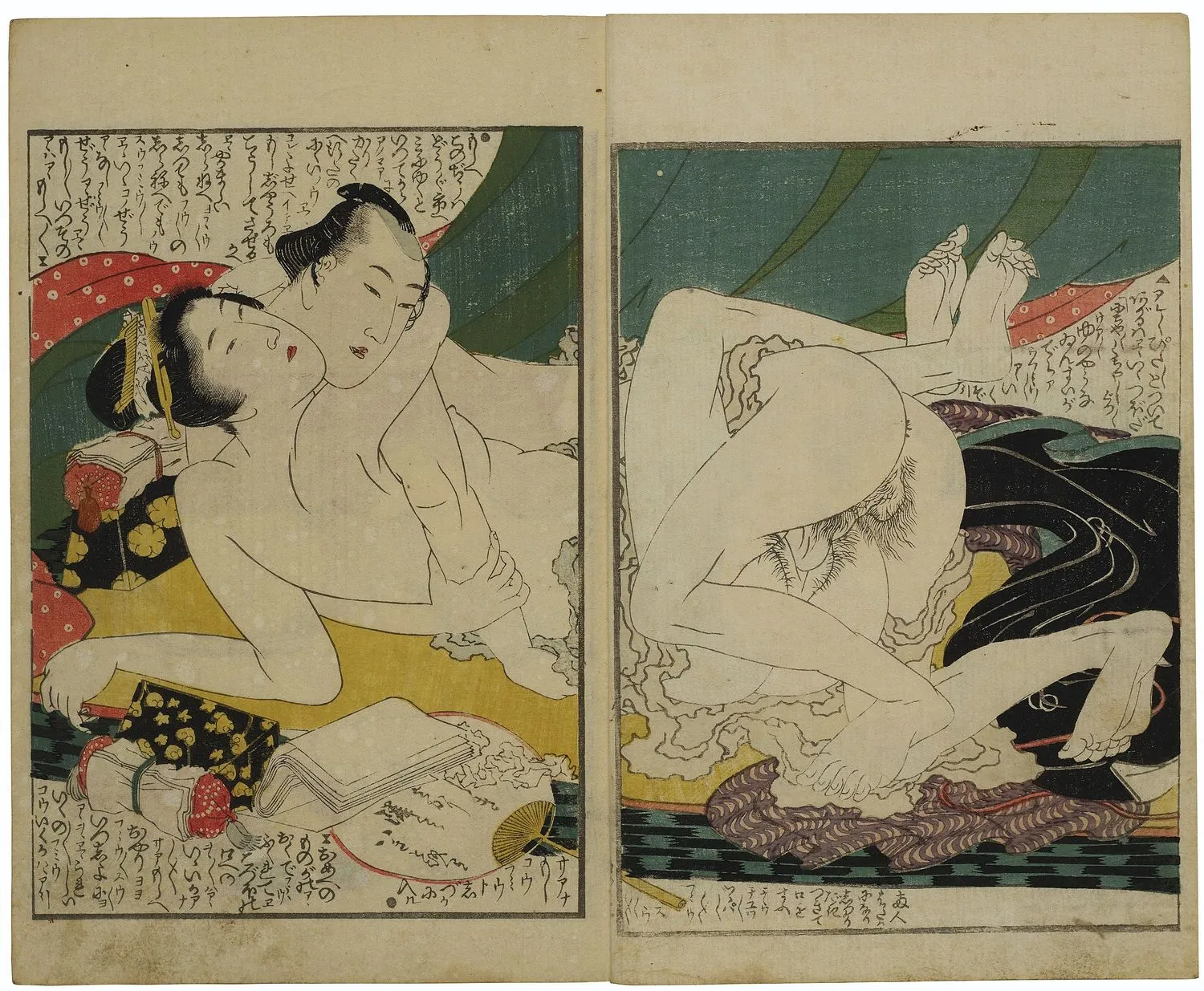

Katsushika Hokusai (1760 – 1849) was the celebrated artist of woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e, which had a profound influence on European art of the 19th century. Ukiyo-e, meaning the images of the floating world, was just one aspect of the rich Japanese visual culture of the time, its subset being provocative and titillating shunga, the erotic prints enjoyed by all social groups.

In 1814, Hokusai created Kinoe no Komatsu or Young Pines, a three-volume book of shunga erotica which includes his most famous work in this genre, The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife (Japanese: 蛸と海女, or Tako to Ama). Known also as Octopus(es) and the Shell Diver, Girl Diver and Octopi, and Diver and Two Octopi, the woodblock print hugely influenced the genre and the related contemporary tentacle erotica that proliferated with manga.

Hokusai's The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife remains one of the most iconic and provocative works in the genre of shunga. The intricate interplay between the figures and the text evokes a complex web of emotions, challenging both the viewer and the reader to confront their own interpretations of the piece's eroticism and symbolism. As the print continues to stir debate about its meaning, it reveals much about the boundaries of representation in art and the cultural context of its time.

Large Octopus: My wish comes true at last, this day of days; finally I have you in my grasp!

Maiden: You hateful octopus! Your sucking at the mouth of my womb makes me gasp for breath!

The famous work by Katsushika Hokusai depicts an ama (a shell diver) reclined across rocks and enveloped in the tentacles of two octopuses. The larger one performs an erotic act on her, while the smaller one wraps around the woman's mouth and neck. The naked woman has her eyes closed in apparent enjoyment, while the octopuses seem focused and determined.

Besides the figures and the rock on which the woman lies, no other visual description of the place is available. However, to add to the expressive imagery, Hokusai wrote a short dialog between the actors, in which the woman seems to resent the giant octopus while at the same time enjoying the erotic act. A further segment from the text reads as follows:

Maiden: Yes, it tingles now; soon there will be no sensation at all left in my hips...Boundaries and borders gone!

Small Octopus: After daddy finishes, I too want to rub and rub my suckers at the ridge of your furry place until you disappear...

The text from the print was translated by James Heaton and Toyoshima Mizuho. Heaton later commented that of all his work, the one that organically found its way from the pre-web period to the digital realm was this text, perhaps because it included a naked maiden and octopuses.

Katsushika Hokusai worked on his shunga prints before he made his most popular ukiyo-e series, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c. 1829 – 1832. While he collaborated with the famous novelist Takizawa Bakin on a series of illustrated books — including the hugely popular fantasy novel Chinsetsu Yumiharizuki (Strange Tales of the Crescent Moon, 1807–1811) with Minamoto no Tametomo as the main character — Hokusai also created a three-volume book of shunga which included The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife as well.

Some Western critics initially interpreted the printed page as a rape scene, but, as the later translation of the text and historical interpretation show, this was not the case. Analysed in the context of the time, the print turns out to be an illustration of a popular story describing a woman's sacrifice.

The motif originated in the story of Princess Tamatori, which was highly popular in the Edo period (1603 - 1867). Tamatori was married to Fujiwara no Fuhito of the Fujiwara clan, whose precious pearl was stolen by Ryūjin, the dragon god of the sea.

The princess vows to help his husband and dives down to Ryūjin's undersea palace, pursued by the god and various sea creatures, including octopuses. To hide the jewel she recovers from the palace, she cuts one of her breasts and hides the pearl inside. In the end, although she manages to run away from her pursuers and reaches the surface, she soon dies from the wound.

The borders of Japan were closed to outsiders until 1853, almost the entire prosperous Edo period, when different aspects, such as communication, technology, and agriculture, improved. Urban culture also flourished, leading to artistic pluralism and unique forms of expression that combined calligraphy, painting, and poetry. The development of woodblock prints also made art available on a scale previously unknown in the country.

The Tamatori story was a popular subject in ukiyo-e art that flourished in this period. Besides Hokusai, other ukiyo-e masters also illustrated its segments, including Utagawa Kuniyoshi and Yanagawa Shigenobu. Some netsuke carvings also include bear-breasted female figures and cephalopods.

Although not so popular when compared to other Katsushika Hokusai works, The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife has inspired artists of later generations to experiment with similar topics and forms.

In the 20th century, Picasso found the painting fascinating and created his own interpretations of the scene. Hokusai's piece is also considered a forerunner of the tentacle-related erotica present in contemporary visual culture.

The motif has been popular in contemporary Japanese animation and manga since the late 20th century and has been popularized by author Toshio Maeda. However, while in Hokusai's depiction, the sexual act between the woman and the octopus is pleasurable, in modern interpretations, this act is often violent and forced, prompting many to connect the change to the turbulent and destructive experiences of Japanese people during the 20th century.

Western popular culture also picked up this theme, including the television series Mad Man where Hokusai's print appears in several episodes, perhaps as a symbol of alpha male power, and it has inspired film director Isabel Coixet for a sex scene in the film Elisa & Marcela.

Although known and present in art for two centuries, the print is still considered somewhat controversial, perhaps for its depiction of an interspecies sexual act. Its contemporary artistic interpretations are equally problematic; in 2003, Australian painter David Laity exhibited a derivative work in Melbourne, provoking a police intervention. However, the case concluded after it was decided that it did not break the city's anti-pornography laws.