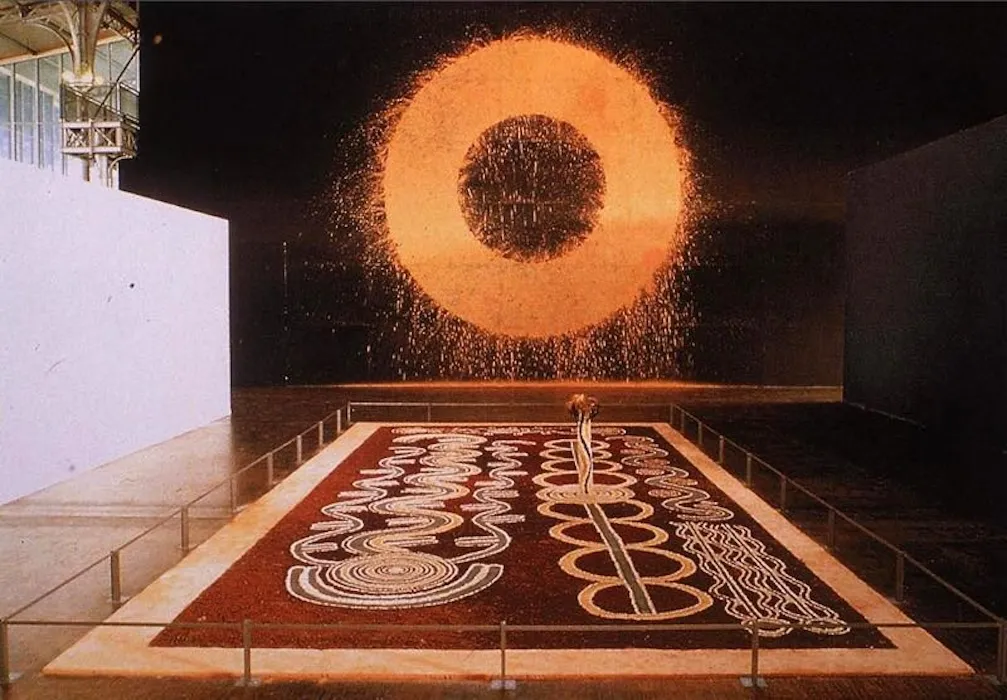

Installation view, Magiciens de la Terre, Grande Halle de La Villette, Paris, 1989 © Jean Fisher

Installation view, Magiciens de la Terre, Grande Halle de La Villette, Paris, 1989 © Jean Fisher Adriano Pedrosa's Venice Biennial gave voice to the Global South, the stranger, the migrant, the marginalized, and the outsider artist. It legitimized and cemented a decolonial discourse within a traditional and institutional framework like La Biennale di Venezia. However, Pedrosa isn't the first to challenge the dominant narrative, and many curators dared chip away at the centralized dogma. Notably, Okwui Enwezor is among the many who stirred the murky canals of the art world with his 2015 Venice Biennale exhibition All the World's Futures, continuing the shift towards global perspectives that began in the late 20th century.

But the doors of art history were unhinged many years before that when Jean-Hubert Martin staged the debatable yet momentous 1989 exhibition Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of the Earth) in Paris. The unprecedented show represents a controversial chapter in art history that has paved the way for underrepresented voices to challenge and break through a Western-centric art world. Its significance lies in the bold claims it introduced, the heated discussions it incited, and the feathers it continues to ruffle after 35 years. It leaves us to wonder: what undertones does the echo of Magiciens de la Terre convey today?

While working as the director of Kunsthalle Bern, Jean-Hubert Martin laid the groundwork for the exhibition in 1984 when he established the criteria for a show highlighting the artist as a creative force. In an attempt to disrupt a Eurocentric framework, Martin wanted to produce "the first worldwide exhibition of contemporary art" that would disregard the nationalistic framework often implemented at various biennial exhibitions.

Preparing for the show entailed lengthy research, lots of travel, and consulting various professionals, such as art historians, critics, ethnographers, and anthropologists. Martin and his team toured the world in search of objects, installations, and practices aligned with the curator's vision. At its core, the curatorial concept emphasized the living artists and site-specific artwork that could be created on the spot.

As explained by Martin in the preface to the catalog, the show was informed by the practices of Joseph Beuys and Robert Filliou, in particular, by their insistence on cross-cultural dialogue and a universal notion of aesthetic creativity. The exhibition intended to present the universality of human creation, thus breaching the barriers that perpetuated the colonial gaze of the Other in contemporary art.

Featuring around 100 artists, Magiciens de la Terre was staged at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Grande Halle de la Villette in Paris under the slogan "one exhibition, two venues." Aiming for equality, half of the artists hailed from the "West." In contrast, the other half belonged to the so-called "peripheries," which, according to the curators, included "artists from the Third World and Socialist countries." Over half of the artists presented their work at the Grande Halle de la Villette, a 19th-century cattle market, with only two-fifths showcased at the Centre Pompidou.

Both venues presented the works with as little didactic information as possible. Labels usually included the artists' names, places and years of birth, nationality, and residence. However, there was an effort to unite the diverse works conceptually with proposed routes that hinted at possible themes, such as birth, origin, healing, and death, without adequately addressing or explaining the specific clusters.

For Magiciens, two famous shows functioned as "negative points of reference"—the 1931 Parisian L'Exposition Coloniale and the infamous 1984 exhibition Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern at MoMA, New York. However, the exhibition demonstrated an inconsistent curatorial approach, highlighting the tension of Otherness that it set out to disrupt. To begin with, the West was represented by well-established contemporary artists, with most of them based in the United States. On the other hand, Magiciens preferred artists from Central and Eastern Europe who have already emigrated to the West, such as Marina Abramović and Krzysztof Wodiczko.

In contrast, the selection of artists from "the periphery” was ridden with discrepancies. For example, the project wholly ignored modernism in non-Western regions, including India, Nepal, Tibet, and Australia, to name just a few. It also disregarded African academic art, giving prominence to works that were marked as anthropological or traditional. Sidelining Arab and Muslim culture, the Middle East was reduced to paintings by Moshe Gershuni and Yousuf Thannoon, but some regions were neglected altogether, such as Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia. Exceptionally, three emerging contemporary artists from China were part of the exhibition, but other than that, Indigenous art from non-Western regions came to the fore.

Moreover, some site-specific works by non-Western artists were subjugated to display strategies of ethnographic museums, including constructing mock-ups of original structures. This includes a replica of Esther Mahlangu's Ndebele house, a faux Tohossou temple for Benin-based sculptor Cyprien Tokoudagba, and a towering iron structure for the bark painting produced by a group from Papua New Guinea led by Nera Jambruk. While aiming to avoid decontextualization, the exhibition arguably did just that by placing traditional and folk works in a contemporary setting, removing them from their cultural contexts and reducing their complexities to visual objects.

In doing so, the exhibition reduced these artists' works to ethnographic displays, emphasizing the "exotic" and "authentic" over their contributions to contemporary art. This raised concerns that some non-Western artists were being framed as anthropological curiosities rather than recognized as contemporary creators. Many critics echoed this sentiment, arguing that the exhibition reinforced stereotypes of non-Western cultures as "magical" or "primitive," thereby perpetuating colonial attitudes that view these cultures through a lens of exoticism. As art critic Hal Foster argued, while the exhibition claimed to create equality, it often reduced non-Western artists to symbols of cultural difference, sidelining the complexity of their work.

Among the many points of contention was the title itself. Martin opted for "magicians" as if timidly shying away from any art-based vocabulary. Instead, the "magic" phrasing implicated an other-worldliness of the exhibited items, pivoting around "a presumed spirituality" that should tie all these works together. "Who Are the Magicians of the Earth?"—Barbara Kruger raised the question in her work for Magiciens. According to Jean-Hubert Martin, they are contemporary, self-taught, migrant, folk, and traditional artists. However, contrary to Enwezor's and Pedrosa's exhibitions, these artists are reduced to "producers of mysterious objects" without a voice of their own. Kruger later recalled:

The exhibition was prescient in terms of the inclusion of different threads of visual practice, but to choose to title it in that way was certainly not a paradigm shift, it was as old as the hills.

In its essence, decoloniality implies looking from within—grounded in recognition of one's own perspective, history, and experience that function as building blocks for a fresh framework to perceive, express, and articulate a pathway, diverging from a discourse infested with self-proclaimed cannons, norms, and rules. As philosopher Enrique Dussel remarked:

It is the struggle for the affirmation of the Other as other, not as the same.

And therein lies Jean-Hubert Martin's detrimental mistake. Intent on tackling Eurocentrism, he pushed for provisional equality, creating visually similar sequences in an attempt to erase the differences that constitute the identities that should have been affirmed. Ultimately, its legacy is within its errors. Because of failing, Magiciens de la Terre became a platform for conversation, critique, and discussion, anticipating a decolonial shift and serving as a vital lesson for future curatorial practices. Identifying its particular issues has paved the way for recognizing the need not only for marginalized voices to be represented but also to be heard by shaping the narrative from within.