Installation view of Ferma by Gabija Grušaitė. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius

Installation view of Ferma by Gabija Grušaitė. Photo: Jonas Balsevicius A subconscious smirk shows up on my face when I meet people who I presume have had no direct experience with war, liberation or post-communism; who (I presume) bear no geographic destiny that moulds you to 'just know'; a destiny that provides you with a cunning, almost, which helps you appreciate, say, a farmhouse full of stuff not as a readymade, but as a portal. It's the smirk of superiority, a defense mechanism that convinces your ego that, by design, you can understand and feel things with more nuance, or as the familiar East–West cliché goes: you approach them with soul.

I come from a country that fell apart in the 90s, where hoarding has become a soothing principle of survival. The sofas in our houses had to be convertible couch beds, in case someone had to sleep on them. Our garages and basements, closets and cupboards were always full of everything but the things they were designed to contain, our freezers were packed with bread saved for later. My mother still keeps her money hidden in a bar of soap somewhere in the house. That's what we call soul.

This kind of soul helps me understand the world of the artist Marius Grušas — father of Gabija Grušaitė, an artist as well, whose site-specific installation Ferma I saw this August in Sariai, Lithuania. Like many fathers of that generation, Marius seems to have started countless projects with enthusiasm, only to leave behind a collection of beginnings. That is the type of father I recognize: one who wanted to turn substance into form, but never had the luxury to stop worrying about the future. Gabija's life is the opposite. Where his was seemingly improvised, hers is mapped out. The European economic order had redrawn the coordinates by the time she came of age, so her future looked more like a layout: rules, boundaries, language. She uses that language literally — as a successful writer — and now as the grammar of her art.

The installation starts way before you enter the house. Whereas some of my European colleagues were worried (and not unrightfully so) about the location's proximity to the national border, my sentiment was actually all about familial relations. We were, in a way, in Gabija's (rather her father's) home, welcomed and served with food and drinks. We had pickles from a jar with a year written on it, and strong liquor called moonshine, in two variations: clear and red — like the moon itself can be. We had wine, endless amounts, meat, and a special kind of fried pastry the word for which I forgot. Cheese. Bees were everywhere, but nobody seemed to mind; and I kept obsessing over potential ticks in the woods around us.

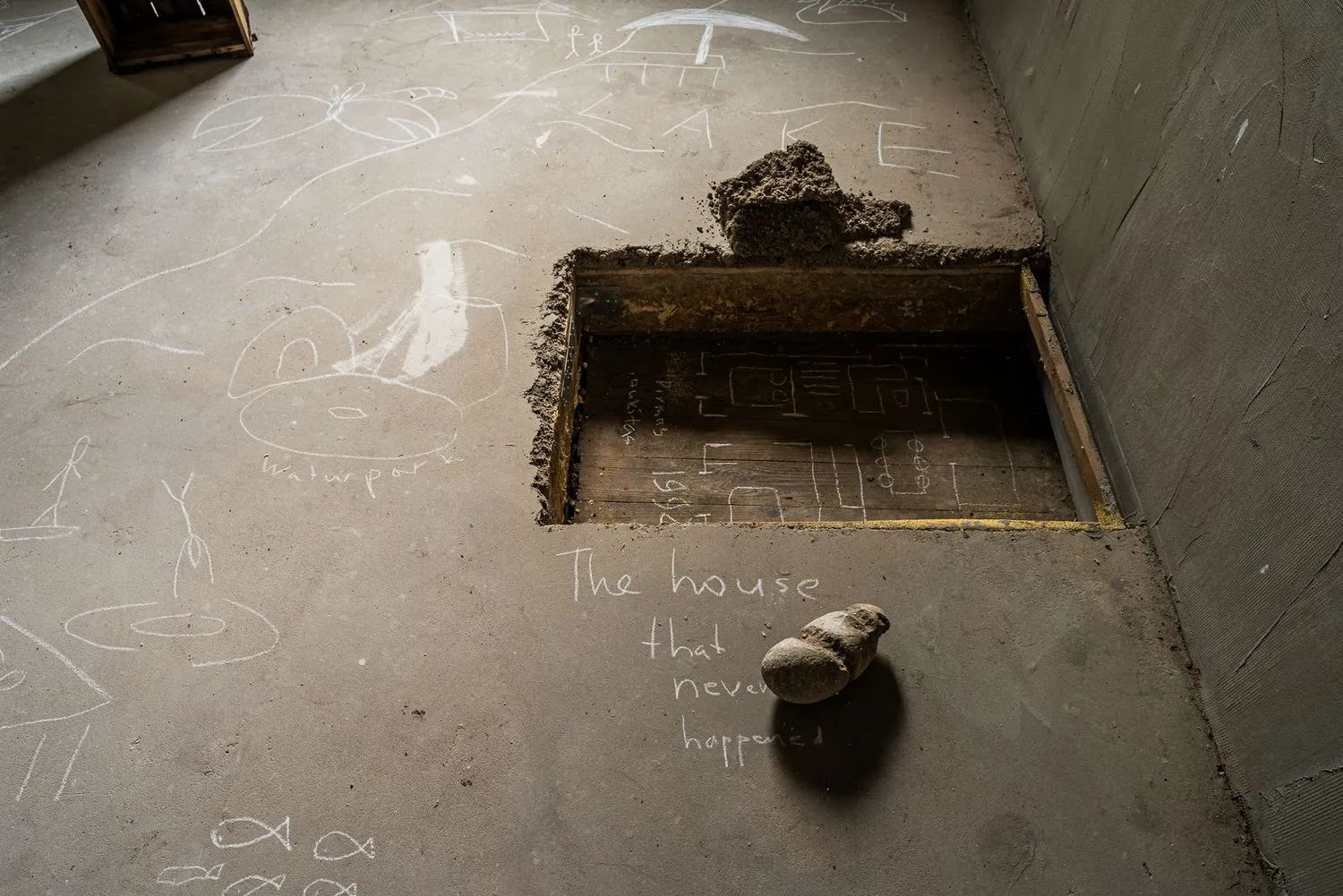

Once inside, there is a room, the kind I know too well from my life in the Balkans. Its surfaces all unfinished, it is functional rather than beautiful, in which lies its aesthetic. Through the small windows, I can see other people roaming around the garden. On the naked floor, there is a map drawn with chalk. It's Gabija's creation: she guides us through a literal blueprint of her memories, a virtual slide with stops that include "Soviet ruins," spots where "normal people live" and associations between raspberries and evil spirits, myths and half-myths from the Baltic folklore and her personal perceptions of reality growing up.

In contrast with the empty room, the shed we enter next is full of things, and this is what Ferma alludes to. The word itself means "farm," as the property had in past been used as a collective dairy farm. What guides you is the sound — it takes you through a countless amount of objects to one of the two sides of this long, rectangular space. At the very end, there is the video projection, barely visible from all the clutter. It's a test for the senses. Everything everywhere all at once: an old Ford parked among it, a pair of pliers, stacks of paintings, books and vinyl records, some toys, a shoe, a mattress, a spindle. "Everything is a potential tetanus risk," said one of the people on the bus on the way there.

I sit on the improvised bench to watch the video. In it, I see the space that I am in, in a different season when it's snowing, inside and out. Through this dioramic mirroring, Gabija actually creates the subject: the liminal space, the border. I can truly feel that my mind is touching something that pushes and pulls like a membrane. It feels like anxiety, as I'm entering someone's both physical and mental private space. Like an invasion.

I wanted to understand what made it special, or different from what I've known about my own world. My anxiety found its subject in an almost microscopic thing—a potentially infected tick that hides somewhere in the woods. The tick is a placeholder. There are things, in the woods, behind the woods, and inside our minds, that are also invisible, and also real, and far more dangerous than the tick. There are things that we have premonition about, but even the war-informed cunning, the knowing I mentioned in the beginning, cannot prepare us for it. Ferma was a place to drop the smirk.

I talked about soul. Perhaps, soul is what you feel between the two identical immaterial video projections, and the larger-than-life tangle that sits so solidly between them. Or, how much space, and what type of space is taken by Gabija, and what type by her father and his own ancestors. My friend Ana Konjović recently coined this one: home is where the heavy is. And if we can agree on anything about Marius's collection of stuff, I'm sure we can agree that it is heavy.

With a voice of solace, Gabija talks about storks toward the end of her piece. They are light enough to fly away in the winter. But they come back—they always do (her words, not mine).

Ferma was a site-specific installation by the Lithuanian artist and writer Gabija Grušaitė, which took place on August 7th, 2025 in Sariai, Lithuania. The project was curated by Francesco Urbano Ragazzi.