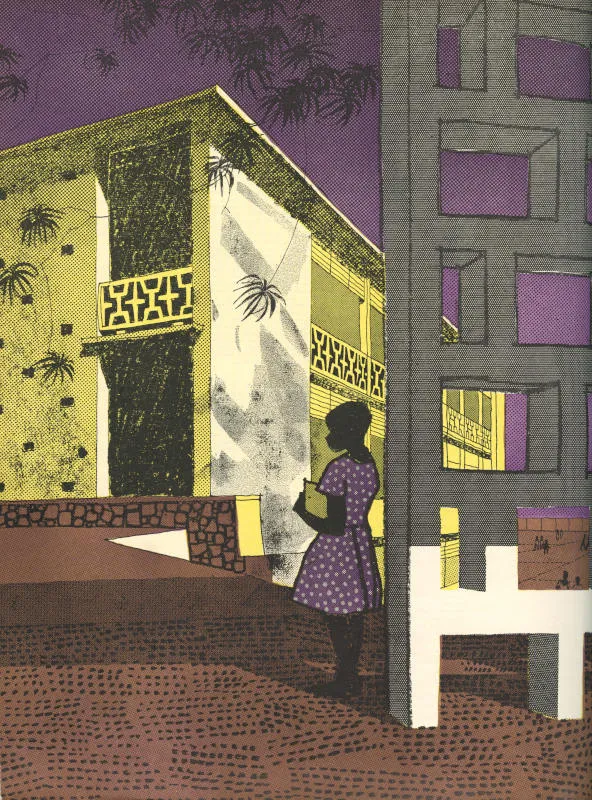

Black Star Square, Accra by Ghana Public Works Department. Film still from 'Tropical Modernism - Architecture and Independence', © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Black Star Square, Accra by Ghana Public Works Department. Film still from 'Tropical Modernism - Architecture and Independence', © Victoria and Albert Museum, London Writing about their designs, which included West African symbols and forms, British architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry described them as 'relics of a beautiful savage life.' The pair traveled to Ghana in the mid-1940s on a mission to change the architectural appearance of the British colony along the modernist tendencies that had been dominant in Europe since the 1920s. Their approach, based on the expansion of Modernist architecture to include local environmental requirements, soon developed into a style and movement known as Tropical Modernism.

However, the history of Tropical Modernism is much more complex than a mere spread of ideas and forms would betray. Modern architecture and its local variant were also deeply intertwined with colonial and postcolonial expansion, where those whose culture and life were deemed 'savage' took control over the narrative and used Tropical Modernism as another building block for their recently liberated nations, along the lines of internationalism and progressiveness.

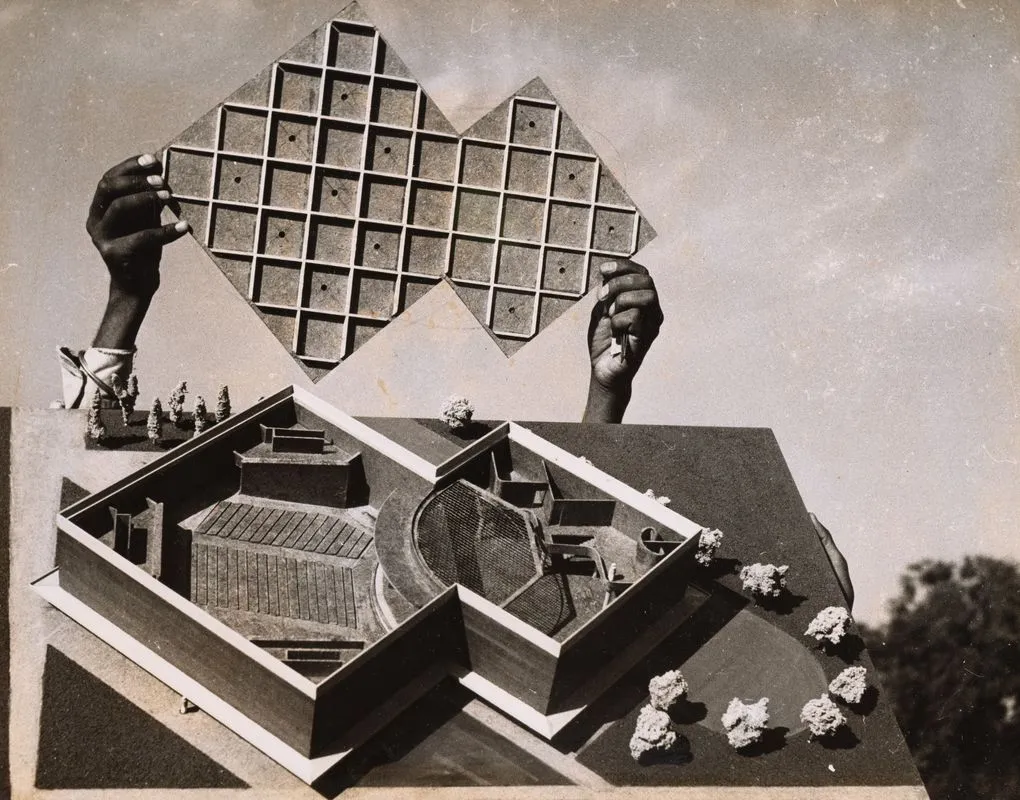

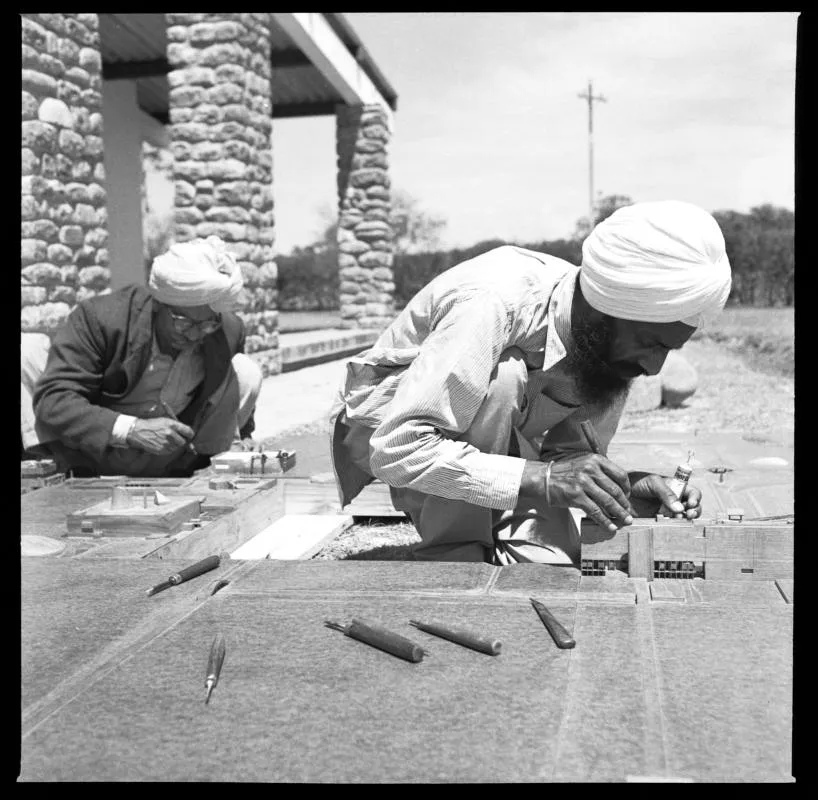

Exploring the rich legacy of Tropical Modernism and its social and political context, V&A South Kensington recently staged the exhibition featuring models and various archival ephemera that bring attention back to this unique style that evolved from its colonial associations into a symbol of postcolonial times.

"The story of Tropical Modernism is one of colonialism and decolonization, politics and power, defiance and independence; it is not just about the past, but also about the present and the future," said Christopher Turner, the V&A's Keeper of Art, Architecture, Photography & Design and Curator of the exhibition.

During the 1940s and 1950s, when voices for independence grew stronger among the colonized nations, the British government tried to suppress them by showing greater interest in local conditions and investing in local infrastructure in West Africa. While Modern architecture failed to take root in the UK, its main proponents, Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, decided to move to the British colony of Ghana and apply its principles to local conditions.

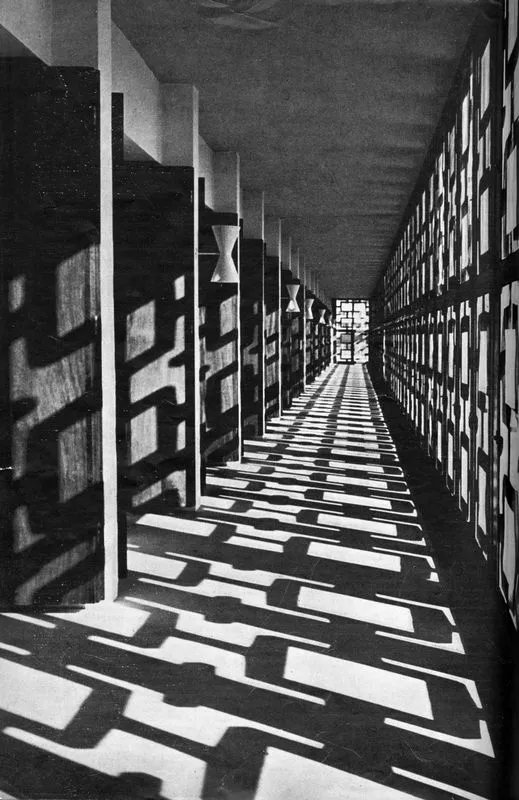

Clean lines, lack of ornamentation, flat roofs, and expanses of glass were the staples of Modernist European architecture that, through its two most prominent proponents—Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius—traveled the globe and became dominant architectural style between the 1920s and 1970s. Tropical Modernism builds on this heritage and ingeniously fuses form and function, adapting the built environment to the requirements of the hot, tropical climates. Its main features include wide overhangs, providing enough shade from the strong sun; open layouts that allow optimal ventilation; and elevated structures to protect from floods. By analyzing meteorological data, architects focused on orienting their buildings along the north-south axis, positioning the shorter sides with solid walls to the East and West to block the sun. The longer sides also featured adjustable louvers and brise soleils, providing passive cooling, shade, and ventilation. The ornamental perforations in the brise soleil often referenced local traditional forms and symbols, going against European Modernism's rejection of ornamentation.

However, Tropical Modernism is much more than a 'derivative' style; it symbolizes the broader movement for emancipation in the Global South and was adopted by its leaders as an expression of modernity that rejected colonial epistemologies. While referring, in its stylistic postulates, to the European modernist tradition, ideologically, the style adopted values and ideas that rejected the European colonial heritage and culture that defined it. Its prime proponents were the leaders of postcolonial Ghana and India, Kwame Nkrumah and Jawaharlal Nehru, and the projects they initiated testify to the movement's strong internationalist and environmentalist outlook.

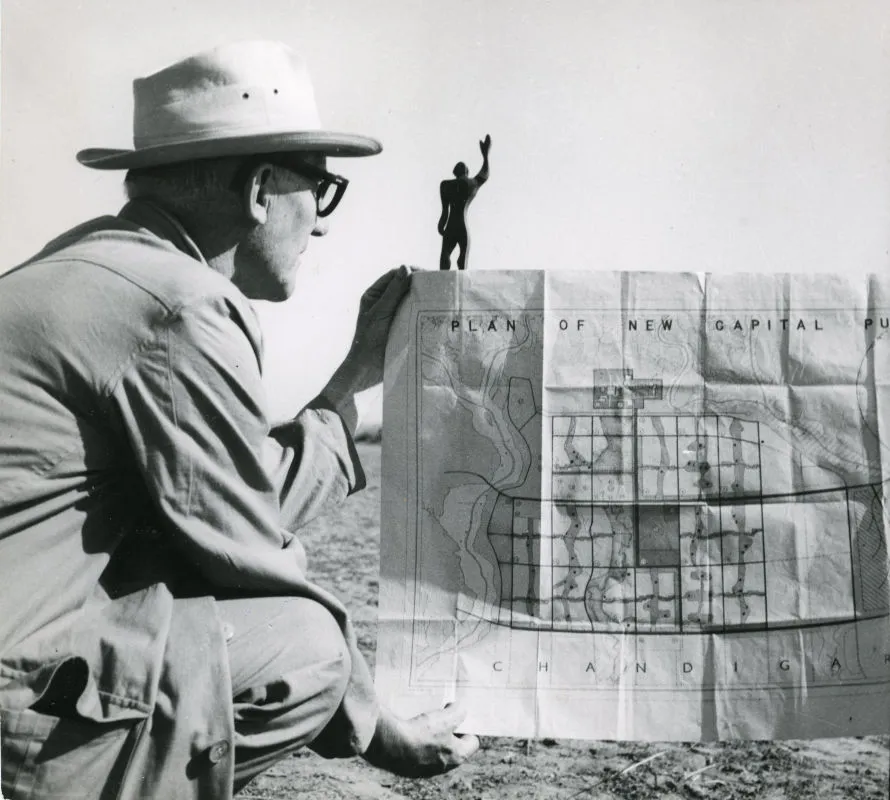

In the immediate aftermath of India's independence and the partition of Pakistan in 1947, the new government led by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru decided to build a new capital for East Punjab to replace Lahore. The outcome: the modernist city of Chandigarh, where locals joined forces with international architects, most notably Le Corbusier, to create a new city for the postcolonial age.

"There is too great a tendency for our people to rush up to England and America for advice. The average American or English town-planner will probably not know the social background of India. He will therefore be inclined to plan something which might suit England or America, but not so much India," explained Nehru.

He insisted on employing local forces in the city's development that would pay heed to local particularities and culture. While the outcome of this attempt was later criticized as it excluded some traditional features of an Indian town, it helped younger architects explore the possibilities of Modernist architecture, including names such as Aditya Prakash and Balkrishna Doshi.

Indeed, it was not Fry and Drew who were the main protagonists of Tropical Modernism, as the prevailing narrative states, but local architects, as Ghanaian architect Nana Biamah-Ofosu, explains for the AD Middle East. Fry and Drew founded the Department of Tropical Architecture in 1954 at the Architectural Association in Ghana, but it was locals who became the leading representatives of the new style that "came to represent newborn countries of independence, hope, and promise." After independence, Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana's new president, urged Ghanaian architects to actively join in shaping the environment of the liberated state, leading to the spread of Tropical Modernism as the dominant style with leading representatives including John Owusu-Addo, Samuel Opare Larbi, Alero Olympio, and Lesley Lokko.

The style that indiscriminately subsumed vast regions of the world under a common name, often neglecting variations of local Modernisms, also continued to shape urban landscapes in later decades. Within the widespread movement of eco-friendly architecture, its visionaries include Ken Yeang and Vo Trong Nghia, who further expanded the possibilities of Tropical Modernism in their climate-responsive creations.

While Tropical Modernism declined since the 1970s, with the introduction of AC systems speeding up its demise, today, when the limits of natural resources are more than evident and their excessive exploitation destabilizes ecosystems worldwide with often devastating consequences, the need to return to sustainable architectural solutions looms large. However, to do so, including reviving Tropical Modernism, without a thorough systematic change would fall short of its goal.

While a more decisive turn to sustainable architecture could help address one issue, the overall effect would be insignificant if the forces that push global climate change are left unchecked. It would be of little help to live in a passive building if global capital and its multinational corporations continue their profit-oriented operations around the world with no or little regard for climate change and the environment.

Instead, a call for an international movement based on ideological principles of the formerly colonized nations that foregrounds solidarity, environmental consideration, and anticapitalism would be in order. Otherwise, Tropical Modernism, revived today, would be just a superficial makeover for the continuation of business as usual.