Àngels Miralda, tour guiado en la Bienal Contemporánea TEA, Tenerife 2024.

Àngels Miralda, tour guiado en la Bienal Contemporánea TEA, Tenerife 2024. Most curators talk, some are experts in looking—and a few run tirelessly. Àngels Miralda is one of them. She describes her curatorial practice as a secret politics of materiality, rooted in the belief that materials carry embedded meanings tied to global chains of extraction, trade, and industry. She curated exhibitions at venues such as the Contemporary Biennial TEA in Canary Islands, Spain, Something Else III in Cairo, MAAC in Guayaquil, Ecuador, and P////AKT Foundation in Amsterdam, among others. She also served as Editor‑in‑Chief of Collecteurs, the world's first collective digital museum, dedicated to creating public access to private collections and keeping the art world independent and open.

Some time ago, we walked the streets of Barcelona to plan this interview, the first of many I hope to conduct with curators. My goal at Loophole is to explore the practice of curating in the global arena: to understand the subjects that keep curators awake at night, as well as their passions and political commitments in troubled times.

In this first conversation, we talk with Àngels about her curatorial ethos, the latest projects, her love of running, and her impressions of Santiago—the city from which I write these lines.

Ignacio Szmulewicz: My dear Àngels, to start, I want to acknowledge your wonderful energy and enthusiastic force in curatorial practice. I see you running almost every day, especially through the mountains. When did you start? And why do you do it?

Àngels Miralda: I started running in 2020, before the global pandemic, and it became a nice way to have some goals during this period and create a daily schedule. Slowly, it became a kind of antidote to the often unfair art world systems that consistently fail to value personal discipline and determination. In running, your own progress is your fair reward for hard work, and I even won some trophies from it. It made me value time and effort, and think of the ways that we create energy and endurance through everyday practice.

In general, the running community is supportive and motivational, which I find lacking within the art world. Despite institutional discourse, that is not a place of solidarity—instead, this is found in the underground cultural communities that are generally kept out of the museums.

Trail running is also relevant to my practice as a curator, as I often look towards materiality and nature. Spending time in the landscape and moving through it freely gives me a unique perspective to discuss our relationship with land, time, and geography. It brings me to places off the beaten path and to rural, sometimes harsh and inaccessible environments.

Ignacio Szmulewicz: I first came across your work several years ago at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MAC) in Chile. Could you share a bit about the exhibition's focus and the artists involved?

Àngels Miralda: Yes, this was my first exhibition within an institutional framework! I really enjoyed working on this project and recreating it with a few of the Chilean artists in different contexts. That exhibition was titled The Base, The Pillars, and the Firmament. It included works by artists including Miguel Soto, Alejandra Prieto, Elizabeth Burmann, Alejandro Leonhardt, and others.

The idea of the exhibition was to imagine the room in the MAC as a core sample of the earth laying on its side. On one side, some artworks had to do with rock and rare earth minerals; later it progressed into soil and buried remnants. At the end, it moved into flora and plantlife, mainly represented by the group CINC (Círculo de Ilustradores Naturalistas de Chile), who have a lot of expertise in the local biodiversity of Chile.

Ignacio Szmulewicz: Was that your first time in Latin America? And how did you perceive the art scene in Santiago?

Àngels Miralda: That was my first time, at least professionally, in Latin America. I went to Chile on the invitation of the residency programme Molten Capital that was run by Benjamin Zawalich and Armando Valenzuela. I met Zawalich during our studies at the Royal College of Art in London and there was the possibility to think about how a curatorial residency could be proposed to an institution like the MAC. I traveled to Chile and spent a month doing studio visits with artists and seeing lots of exhibitions in galleries and museums, and getting into in-depth discussions about the local art context late into the night at bars and artists' houses. It gave me quite a good overview of Chilean art, and after the closing of the exhibition, I continued working with a few of these artists in other contexts.

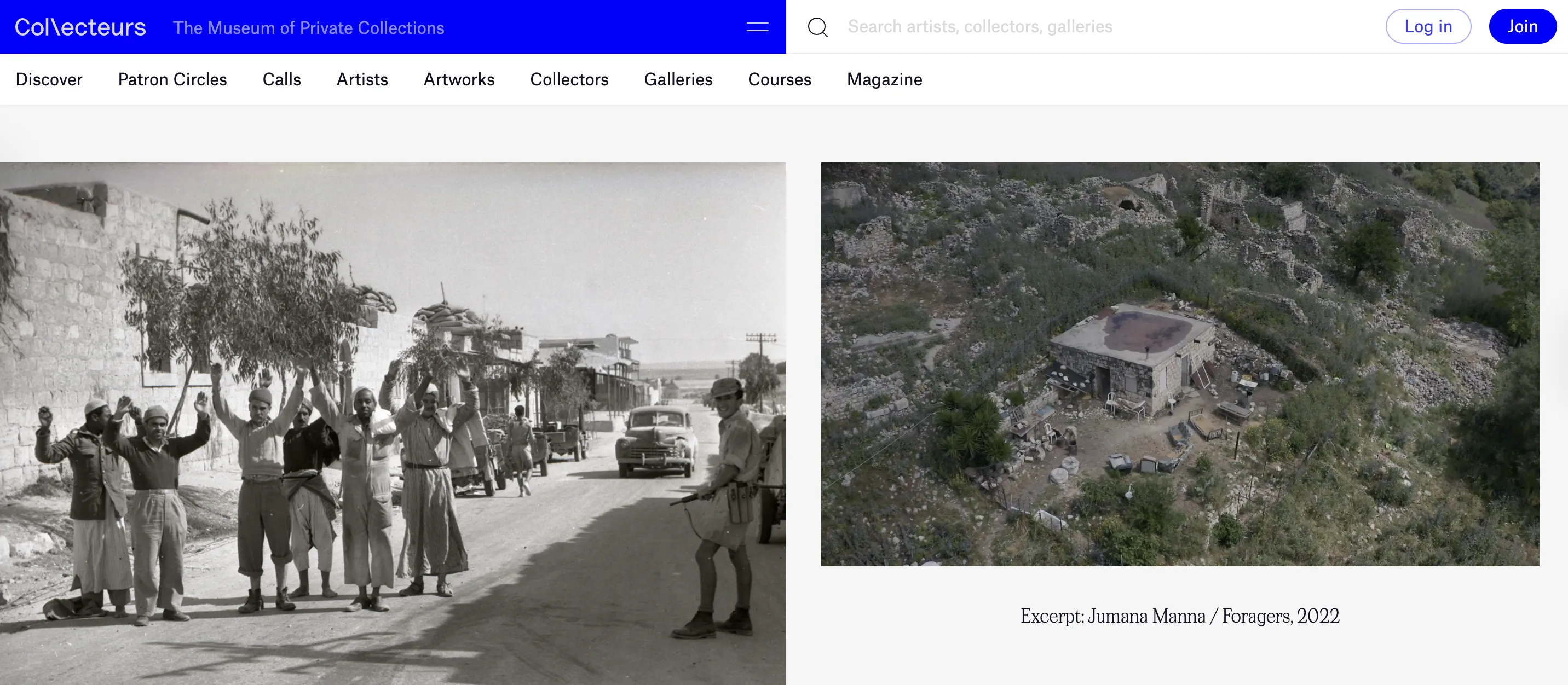

My impression was that there were many interesting voices, but that it was difficult to move work due to distance. Despite this, the Chilean context provides valuable insights and theoretical discussions of relevance on a global scale—from the postcolonial context to indigenous land struggles, community and social change. Recently, with the conversations on Palestine, I have worked with Chilean artists such as Nicolás Jaar and Francisca Khamis, who come from the significant Palestinian diaspora in Chile. All of these subjects are both local and central on a global scale. Back in 2017, the artistic context in Chile became the ground for my opposition to binary logics of local and foreign as they are perceived from the Eurocentric lens.

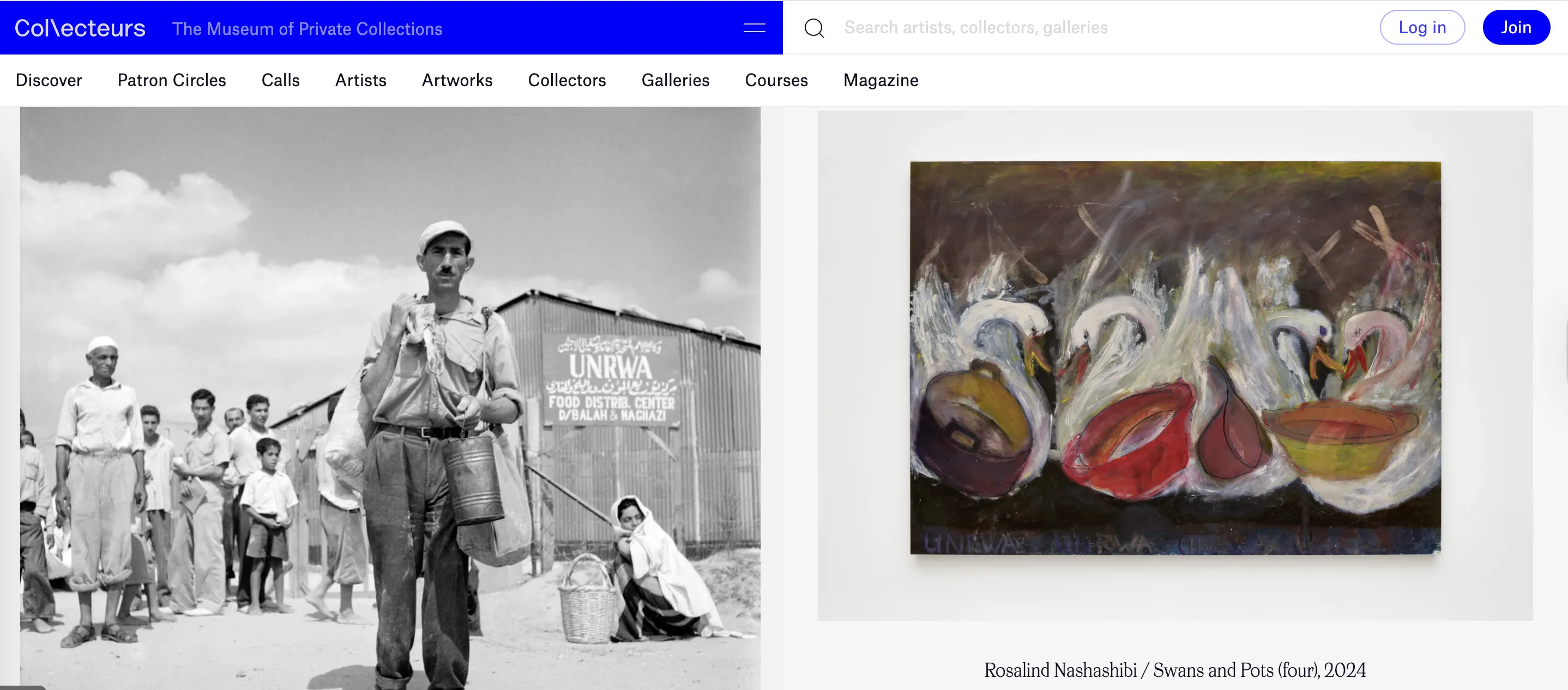

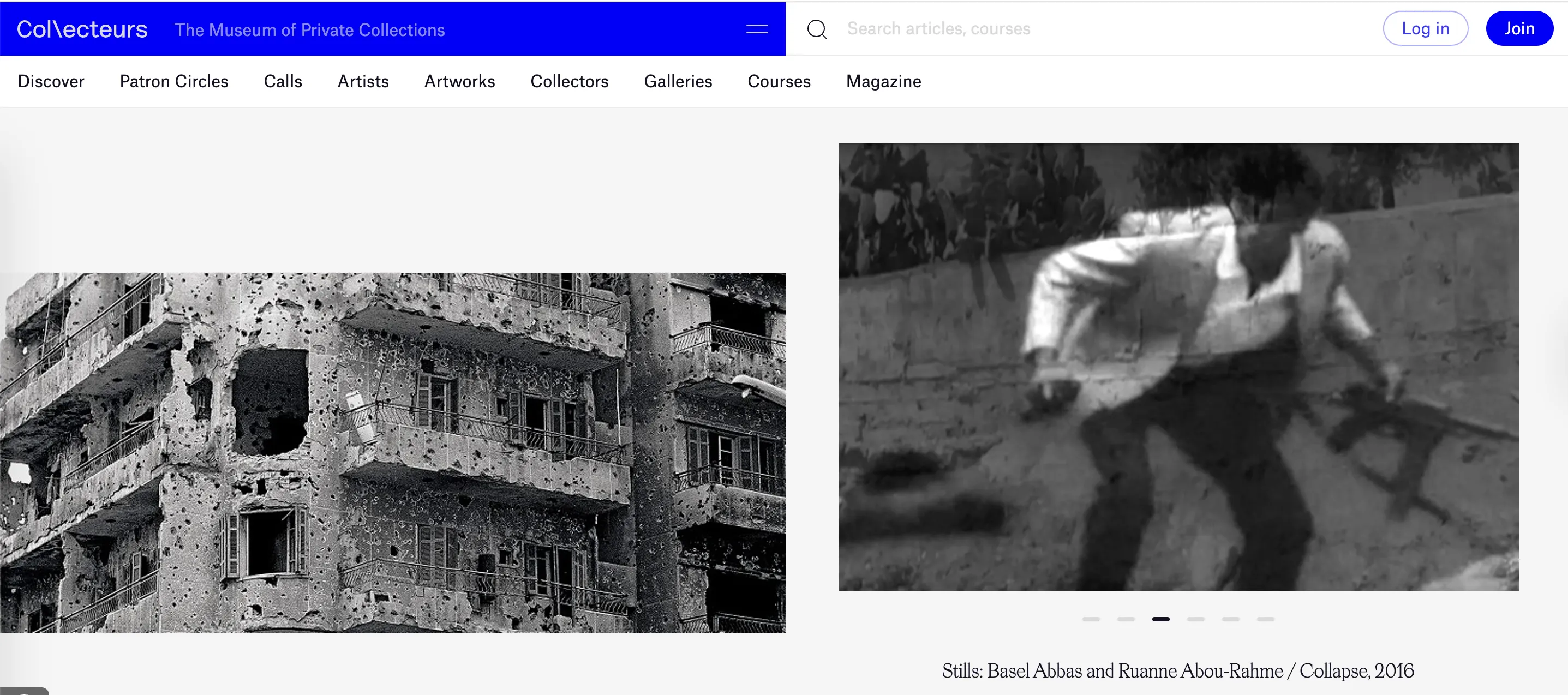

Ignacio Szmulewicz: You worked with Jaar and Khamis while you were editor-in-chief of Collecteurs from 2021 until mid-2024. How did your work as editor evolve during that time, and how did it shift as the platform increasingly focused on Palestine and broader political issues?

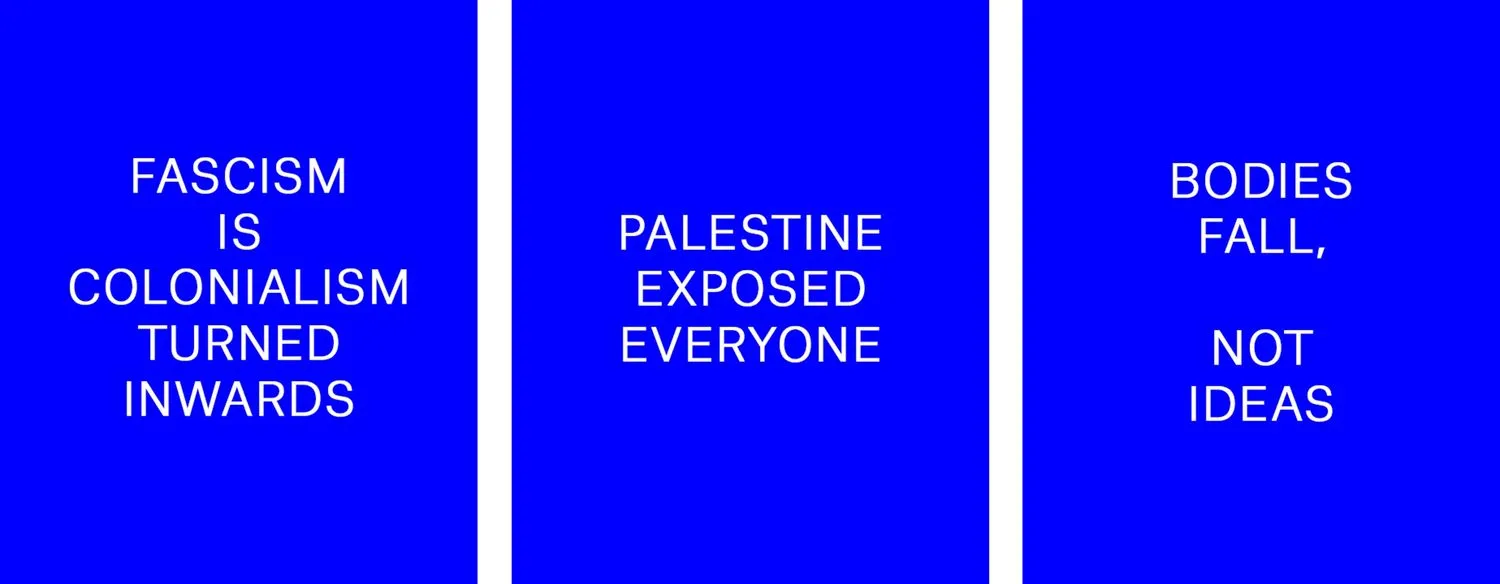

Àngels Miralda: I deeply value the time I spent at Collecteurs and everything that we built together as a team. Although our Instagram account was deleted, I think many people globally have the imprint of the blue Horrorscope posts burned into their memory. At that time, I was also a contributing writer at Artforum, which fired its editor, David Velasco, over a statement in support of Palestine. During the fallout of this process, we at Collecteurs, as a team, decided to go all out until the ceasefire. We all felt the urgency of it—the absurdity of life continuing in parallel to live-streamed genocide. We had spent years working together to build guidelines for ethical collecting, and it was a beautiful moment to realise that we all shared this basic human value as well.

Ignacio Szmulewicz: As Collecteurs focused more on Palestine, the platform faced serious challenges, including political pressure and censorship. How did that period affect the team, the platform, and your own view on the role of independent art platforms in politically charged contexts?

Àngels Miralda: There were immediate consequences to our decision. Many collectors left the platform, and we received harassment in various forms. I feel very fortunate not to have been affected as strongly am a Spanish citizen, and in general, we hold quite pro-Palestinian views. The Turkish members of the team were similarly supported by their own immediate surroundings. But you can imagine how difficult life was for the team living in the United States. It was tough, and I am forever in awe of their moral fortitude in withstanding that time while staying true to their values. It's not the same to join a protest there as it is in Barcelona!

Ignacio Szmulewicz: The last time we saw each other was actually in Barcelona, walking the streets of Raval, Gothic, and Born. You showed me Àngels Barcelona Gallery and the Joan Brossa Museum, and we ended up having coffee in a small square, where we talked about your experience curating the Contemporary Biennial TEA. Tell me more about that experience?

Àngels Miralda: It was wonderful! The Contemporary Biennial of TEA was co-curated with Raisa Maudit. I really enjoy collaborations with other curators because there is another voice there to bring the project in unexpected directions. With Raisa, we managed to find a strong common ground, but also to show each of our interests within the main concept. This was a very unique biennial—it was the first edition, and that always makes it more difficult because there is no template to follow. Additionally, the biennial was made entirely from an open call, which meant that Raisa and I did not develop an idea and then invite artists we already knew who fit that theme.

We did a reverse process, we made a large selection of portfolios that were all of a very high quality and then created a subject by finding links between various of these portfolios. We received almost one thousand proposals from all over the world, so this was the most difficult part, as there were so many artists we would have loved to include, but that we couldn't fit into the budget.

In any case, I still remember a lot of those portfolios of artists whom I still want to work with and invite somewhere, and I would love to have another opportunity to collaborate with Raisa again. Like any project of this scale, its success is also due to a highly professional team at Tenerife Espacio de las Artes. It was a transition moment between one director and the next, but we received a lot of support from both the outgoing and incoming directors, as well as the dedicated team.

Ignacio Szmulewicz: After that, you went to Egypt to open the Cairo Off-Biennial called Something Else. We were taught in Art History about the Pyramids and Ancient Egypt, but we lack much information about Egyptian contemporary art. How did you find the art scene there, and what interested you the most

Àngels Miralda: Egypt is an incredible place, everything is there, but that includes a lot of difficulty, both economically and politically. In Cairo, I successfully made my second exhibition as part of Something Else, which is an Off-Biennial organised by the cultural organisation Darb1718. I really admire the Artistic Director Simon Njami's pan-African vision and the way he has been able to create space for art in very difficult contexts, and I am proud to have been a part of this.

Despite all of the difficulty, the lack of financing and cultural infrastructure, I have met great artists with unique visions who I hope to work with on future occasions. For my subject of landscape and identity, I am fascinated with the Islamic and specifically Sufi view of the desert as a metaphorical space for divinity. In this edition, I was able to commission a new video work from the Turkish artist Kubilay Mert Ural, who created a script featuring a dialogue between politicians and a dervish driving among the pyramids of Giza.

Ignacio Szmulewicz: Soon after, you crossed the Atlantic to curate a solo show of works by Paul Rosero Contreras at the Anthropological and Contemporary Art Museum in Guayaquil, Ecuador. Could you tell me more about the artist and this project?

Àngels Miralda: Paul Rosero Contreras is an internationally recognized Ecuadorian artist who has consistently made works following his unique philosophy on art and ecology. I admire him a lot because he is one of the artists who I see today paving his own way—not riding waves of trending thematics but diving into a field of his own making and following through with it. I first worked with Paul Rosero in 2017 at the MAC in Chile, when I curated a selection of artist films for a public programme. Later, we participated in a truly eye-opening production residency called Re_Act in the Azores Islands.

The initiative was run by Paulo Ávila and Paulo Arraiano, who organised a stay and exhibition in the Museum of Angra do Heroísmo on the island of Terceira. My idea there was to connect Paul's existing project on the Galapagos Islands to the Azores. On the islands, he was able to identify plants whose origins came from Ecuador and that were brought there along colonial trade routes with the intention of creating new markets in Europe.

After all of these years of working together and developing projects along our shared interests, it was a special opportunity for me to show some of these works and others in this large-scale solo exhibition in the amphibious spaces of the MAAC in Guayaquil. I was able to go even deeper into his work and process.

Ignacio Szmulewicz: I am always curious how a curator selects their next project. Is it a theme, a region, an artist, a commission?

Àngels Miralda: I wish I had that much agency! As a curator, one of the most important skills you can have is thinking about feasibility. With the limited resources I have as an independent curator, I rely pretty heavily on the invitations of institutions in order to go forward with my practice. Once I receive an invitation, this is never carte blanche, even if you think it is. All institutions have needs, local audiences, contexts, and restrictions. It's part of my work to take all of these things into consideration in order to propose the best fit for the space, its audiences, as well as my own vision.

At the moment, I am trying to focus my work in my immediate context of The Netherlands, where I currently live and Spain, my home country. However, I am a sailor at heart and get wildly curious about the history and artists of many different regions and countries. When I arrive somewhere and become curious, I do a deep dive, and it's hard to get me out of there. I try to keep those connections alive as long as possible—as I have with you and other friends from Chile! I try to keep this alive through conversations and invitations to collaborate as much as possible.

Ignacio Szmulewicz: I have also read several of your reviews, articles, and texts for catalogues. What do you like about art criticism?

Àngels Miralda: I actually hate art criticism. I say that with a grain of salt. At least the art criticism of today is a watered-down version of something that used to matter. There is no space in today's art world for criticism—magazines act as advertisers for art spaces. You almost never see negative reviews anymore, and when you do, it is not about art but about politics. This dynamic defeats the purpose of art altogether, which is to have conversations and to disagree. Many exhibitions speak about chora or multiplicity of voices, yet the art world strategically creates a stranglehold for everyone to say exactly the same thing in unison. At the moment, I am writing reviews only of artists I want to support from an ethical standpoint, as well as critical articles about the structures of the art world that are producing these unwelcome changes, such as Who Killed the Independent Curator?, recently published in Frieze.

Ignacio Szmulewicz: Finally, being an independent curator and writer, in these troubling times of censorship and political struggles, how do you maintain your focus and love in contemporary art?

Àngels Miralda: At Collecteurs, we went all in for Palestine in 2023. Whatever difference it might have made or not, I know on a personal level that a moral code developed during that time—one that cannot go back to a period before the atrocities.

I think this is the perfect point to go back to Egypt and end there. I feel that in these political climates of censorship, a place like Cairo is exactly where you can see the reality most clearly. People in Germany and the United States should learn from the Egyptians—they have decades of experience in how to deal with these situations and find ways to speak in secret outside of the false veneer of freedom of expression. These artists give me hope in solidarity and our common survival in the dark times we are entering by living a radical, long-term political endurance.