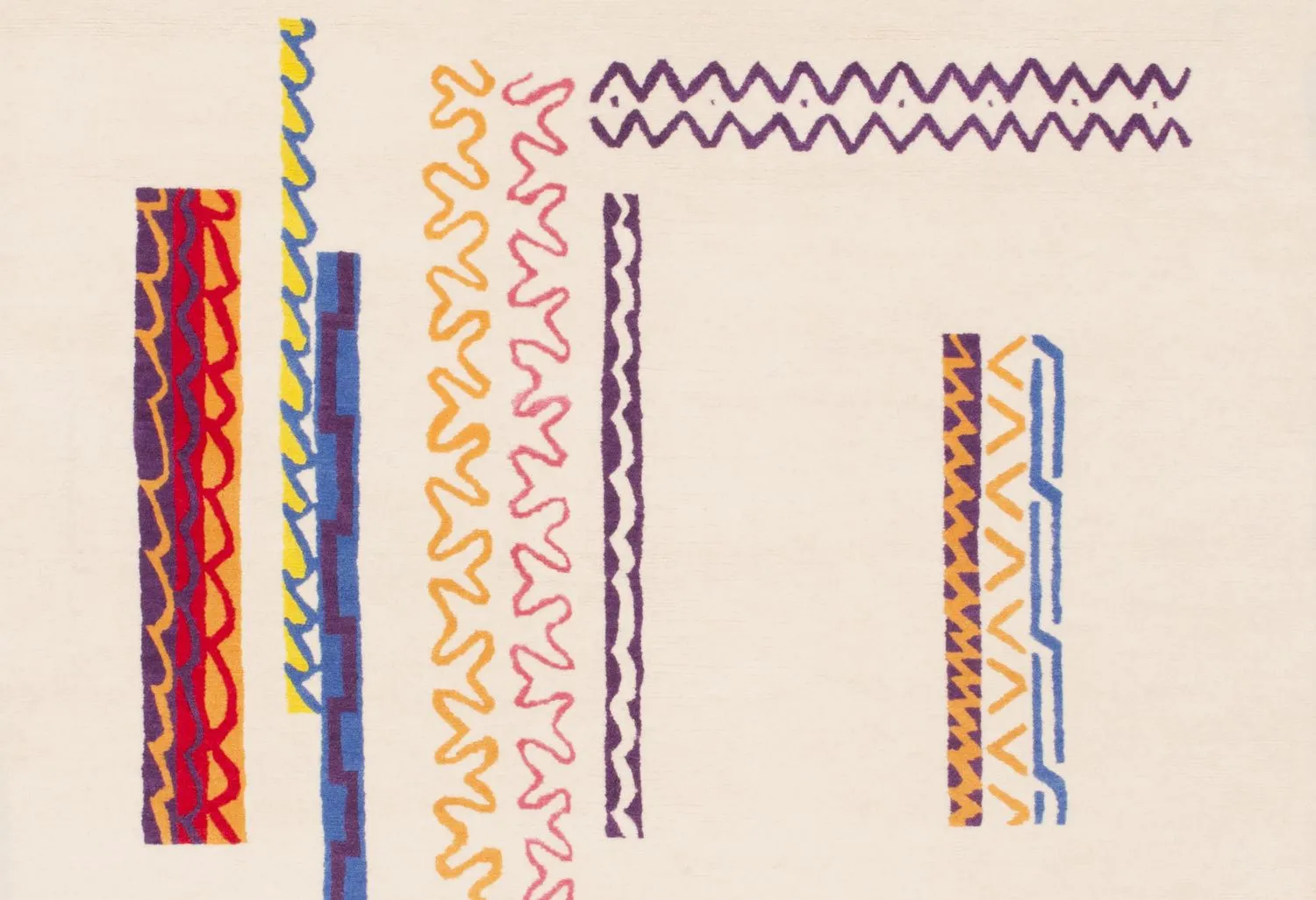

Mekhitar Garabedian, For God's sake, keep it away from candle and oil and hold it with a white cloth, I beg you (detail), 2025, handmade carpet, wool and silk, 120 x 120 cm. Courtesy of N.Vrouyr

Mekhitar Garabedian, For God's sake, keep it away from candle and oil and hold it with a white cloth, I beg you (detail), 2025, handmade carpet, wool and silk, 120 x 120 cm. Courtesy of N.Vrouyr Mekhitar Garabedian's work navigates the fragile terrain between memory, language, and heritage, tracing the ways personal and collective histories are preserved, fragmented, and translated across time and place. Drawing on his Armenian diasporic background, he examines how displacement shapes identity and how inherited narratives continue to echo across generations. Working in drawings, texts, installations, photography, sound works, and textiles, Garabedian treats language, family archives, and historical references as materials, crafting layered compositions that make intimate and often overlooked histories visible.

For his latest project, Garabedian turns to Armenian medieval manuscripts, focusing on the ornamental margins where monks allowed themselves improvisation and play. These patterns become the foundation for two new carpets created in collaboration with N. Vrouyr, whose long-standing expertise in weaving and craftsmanship provides a rare dialogue between contemporary vision and traditional technique. The carpets will be first presented at BRAFA 2026, taking place between January 25th and February 1st 2026, at the Brussels Expo, offering a new encounter with Garabedian's ongoing engagement with cultural heritage, ornament, and language.

In this conversation, we explore how diaspora and multilingual experience inform his approach, the ways in which language and ornament function as both material and concept, the sensitivity to margins, the fragility of heritage, and the dialogue between Garabedian and the Vrouyrs that shaped these recent carpets.

Jelena Martinović: Your work often engages with migration and diasporic experiences. How has your personal and family background shaped the way you approach themes of memory and identity in your art?

Mekhitar Garabedian: I was born in Aleppo, Syria, where my father was born and raised. My mother was born in Beirut, Lebanon. My parents are Armenian by descent and were both raised in Armenian communities in diaspora. Their parents and grandparents lived within the then large Armenian communities in Anatolia, which is now Turkey. In 1915-1916, they had to escape the Turkish atrocities and massacres during the Catastrophe. The generation of my grandparents grew up in orphanages, in their case in Syria and Lebanon.

My father used to work in Aleppo and Beirut and his job frequently took him to Europe. My parents wanted to settle themselves in Beirut, but because of the civil war in Lebanon, among other things, my parents decided to relocate to somewhere central in Europe and by accident that turned out to be Belgium. My parents carry with them the Middle Eastern culture, history, and the Arabic language with which they grew up. This personal sketch already shows some of the complexities of diaspora.

I not only share an Armenian ethnic origin, but also a diversity of cultural capitals or presences collected from different countries of migration: Anatolian, Syrian, Lebanese, and broader Middle Eastern presences, combined with a Belgian present/presence. These places and their histories, as well as their contemporary political, economic, and cultural situations, are meaningful, significant, and vital presences in my daily life. Diaspora means experiencing a disseminated, shattered, divided self.

In diaspora, both the old and the new, the original family and the new community, their languages and cultures, appear equally attractive and problematic, resulting in a subjective condition marked by longing and belonging, and by always being in between cultures, times, places—layering, contaminating, and balancing different pasts, presents, and futures—being here, and, at the same time, always already there. It means to keep feeling threatened by this past, by this former territory, and to be caught up in memory, the memory of a happiness or a disaster—both always excessive. Diaspora means being rooted in metaphor, symbols, history or family, rather than in one place.

Jelena Martinović: Many of your works are concerned with language and its limits. How do you work with language as a material, and what conceptual possibilities does it open up in your practice?

Mekhitar Garabedian: Diaspora is marked by translation. Inhabiting two or more languages concurrently challenges our subjectivity, as we are pending, undecided, between two languages. Bilingual or multilingual consciousness is not the sum of two languages, but a different state of mind altogether—defined by the mode of translation. You find yourself in a position in which you can no longer speak of a mother tongue—always in between (two, or more) languages, always speaking the words of others.

Language has appeared in different ways in my work, as I have tried to understand its significance in our lives. My mother, quite rightly, says: "Hearing our language is a joy for us." My maternal language is Western Armenian, a language in the process of disappearing, increasingly with each successive generation. Western Armenian was spoken in Anatolia and became the language of education and culture for the Armenians of the diaspora: mainly the Middle East, but also France, the US and Canada.

The poet, novelist, and literary critic Krikor Beledian writes: "It is understandable that we lose the language when its place disappears, when its country essentially vanishes from sight, unguarded and forbidden. Language becomes abandoned, a dialect stripped of land, something I have called an un-peopled language." The disintegration of the mother tongue experienced through migration in general and by the Armenians living in the diaspora specifically, is a central concern in my research and work.

Most Armenians of the diaspora are bilingual, if not multi-lingual and/or multi-dialectical, and each language serves a certain purpose and/or context. At different ages, too, people make transitions between languages, changing the emphasis from one to another. Yet there is an evolution towards a monolingualism of the host language.

Armenian is a language I was never taught (in school), which I speak with an intuitive grammar and with a limited vocabulary. I speak it, but I barely read or write it, so that very few or no new words are added to my basic vocabulary. I only use it with my immediate family. My Armenian is a language that is in the process of disintegrating without ever leaving me. Dutch is the language of my scholarly education, the language of my public (and intellectual) life. It is the language I speak with my partner, yet Dutch will never feel as completely mine and while Armenian might be the language I dream in, it also does not feel completely mine.

In addition to Armenian and Dutch, my parents used a third language, Arabic, the language of their education and public life, which they employed as a secret code in regard to us, their children, when they wanted to discuss something in private. Language has the power to create an immediate sense of inclusion or exclusion. If you want to stigmatize someone as a foreigner, simply speak a language he or she does not understand in their presence. The subtleties and differences in the language we speak can unite as well as distinguish us. Edward Sapir, the anthropologist and linguist, states: "He talks like us" is equivalent to saying "He is one of us."

Jelena Martinović: Your work often navigates the space between personal memory and inherited collective histories. How do these layers interact or shape each other in your practice?

Mekhitar Garabedian: I touch upon different kinds of memory in my work. One is postmemory. Diasporic subjectivity is marked by postmemory; to grow up dominated by narratives that precede your birth. Even though the Catastrophe did not take place in my lifetime, nor in that of my parents, the narratives and experience of that history had a major influence on us (with differences for each generation). These experiences were transmitted so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right.

To grow up with inherited memories means to be shaped, however indirectly, by fragments of events that still defy narrative reconstruction and exceed comprehension. These histories are not merely narratives of a faraway past disconnected from contemporary subjectivities and memories; they are also histories of the present. The legacies of displacement and dislocation are critical features of the present, their effects continue into the present.

Diaspora is marked by a loss of a place, a vanishing of culture and traditions, and by living with melancholy about an abandoned period of time. There is a loss of a place and of a time, which cannot be recuperated or recovered, but which leaves its ambiguous traces. What has been lost, or left permanently behind, keeps returning, haunting, and continues to determine the present and one's identity. The temporality of diasporic subjectivity is haunted by the past.

Diasporic subjectivity is defined by montage, by a multiple exposure of different times and places. It means living in an unhomely world, with all its ambivalences and ambiguities of having lost home and feeling out of place. Diasporic subjects are continually confronted and occupied with questions about how to translate different pasts into the present. They experience time and history out of joint, haunted by the past, by an other time, another life, other countries and languages, and so on. They live in different time zones at once, always asking, "What time is it there?"

Jelena Martinović: For the carpets you created with N. Vrouyr, to be shown at BRAFA, you draw on Armenian medieval manuscripts, especially their ornamental margins. What led you to this manuscript tradition, and why did you choose to focus on the margins rather than the center?

Mekhitar Garabedian: I have always been engaged with and researching heritage; Lebanese, Syrian, Armenian, Belgian, etc. In September 2020, Azerbaijan invaded the Armenian enclave of Artsakh (also known as Nagorno-Karabakh). In September 2023, after an illegal blockade of almost a year, during which fuel, food and medicine were withheld from the population and the delivery of humanitarian aid was prohibited, Azerbaijan launched another military offensive.

By October of 2023, almost the entire native population of the region had fled to Armenia, marking the end of the millennia-old Armenian presence in Artsakh. Ethnic cleansing, displacement and dislocation became a reality for Armenians again. The region's rich architectural heritage is still at risk and many historic early Christian churches and monuments may face destruction now that they are out of Armenian hands. This tragic event led me again to explore the fragility and weight of cultural heritage.

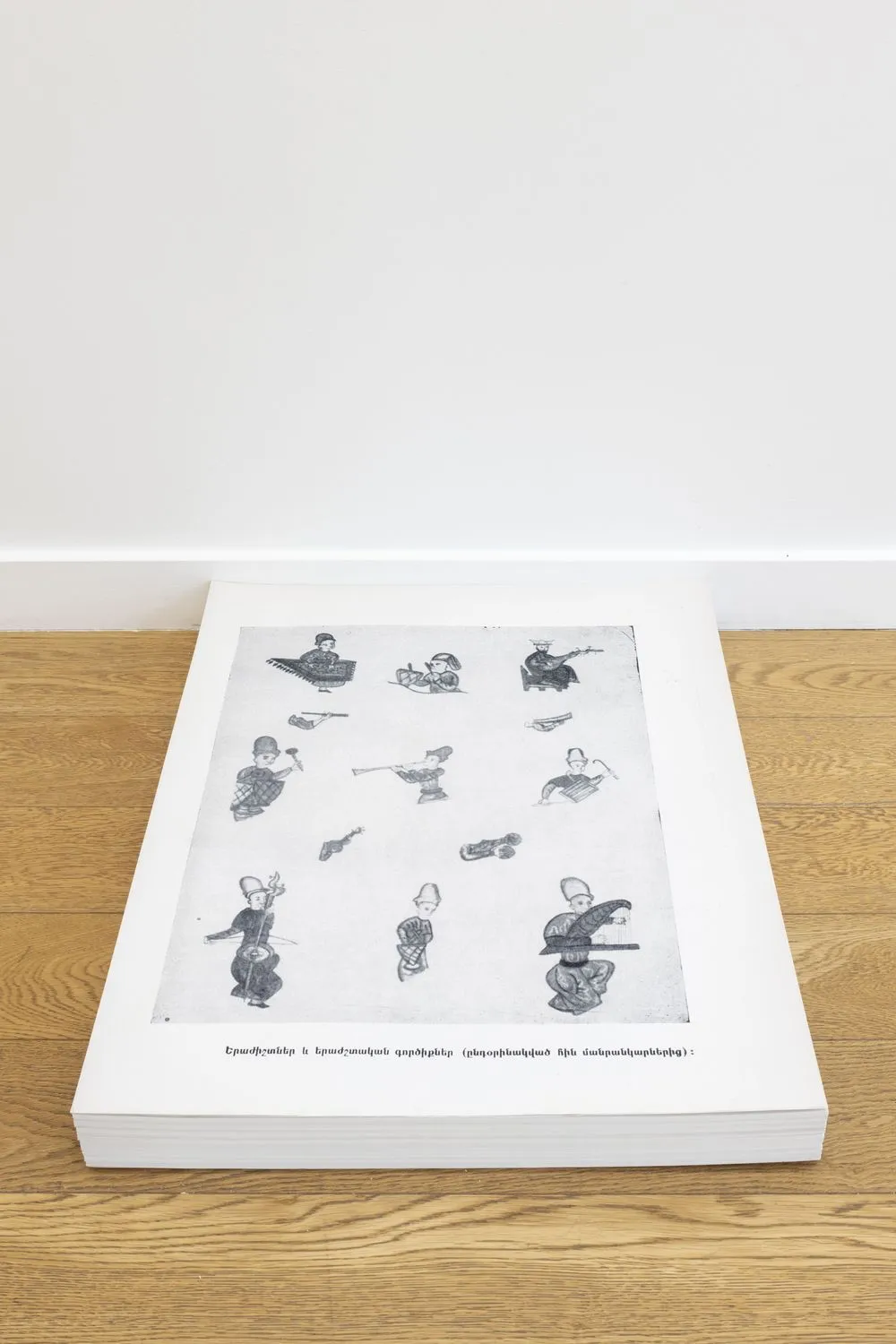

While preparing for a project, I was reading about Komitas, the Armenian priest and musicologist. By chance, this led me to discover a medieval drawing of musicians. Through these rare medieval depictions of musicians, I started looking with more attention to the tradition of copyists and medieval illuminated manuscripts. At that time, I was making drawings, mostly just for myself, in which I was exploring patterns and ornamentation.

Gradually, I started making compositions with the ornamental patterns drawn by the monks in the frames of the religious scenes. Because these patterns were in the margins of the images, often ignored or neglected, the monks could allow themselves more freedom and experimentation, unlike the religious scenes for which there were traditions, and thus rules, to follow. The ornamentation feels surprisingly modern, when isolated. The colours have remained vivid in these books and the colour combinations are playful. It resonated with research I was doing on textile works and artists like Sophie Tauber-Arp, Sonia Delaunay, Mohamed Melehi, Etel Adnan, and many others.

Jelena Martinović: The titles of the carpets are unusually long and expressive. How does language function within the works alongside the designs?

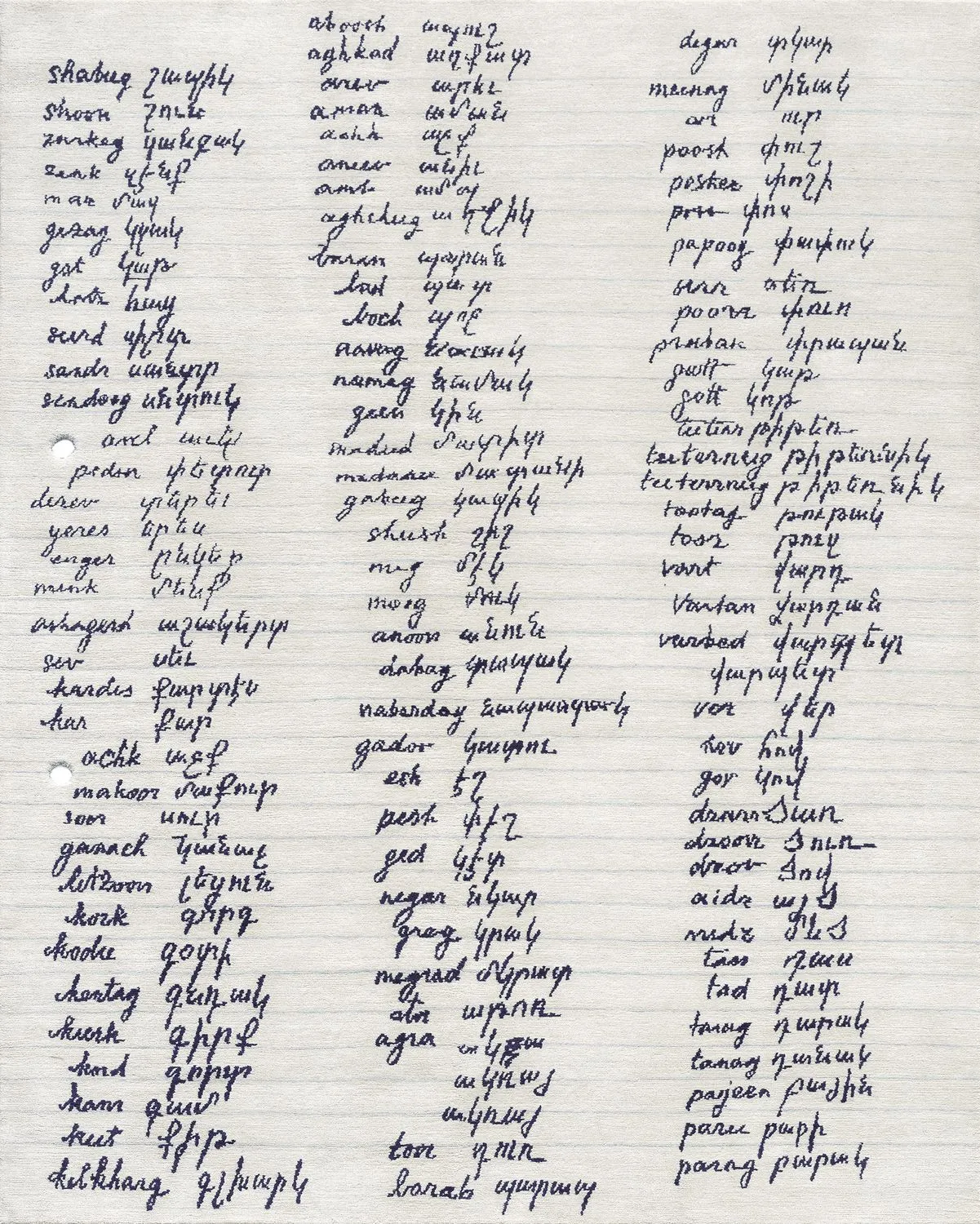

Mekhitar Garabedian: In the fourteenth century, the Armenian copyist Aleksianos complained about the conditions in which he had to perform his duties as a monk: "I am asking for forgiveness for my scribal errors, because my friend is a babbling chatterbox." During the Middle Ages, a unique tradition emerged among Armenian copyists to outline in the colophon the political, social, or personal context in which they did their work. The constant threat of hostile populations is a recurring theme in these colophons, which are often annotations of eyewitness accounts. These colophons provide valuable historical and often surprising information about the sociopolitical context as well as the personal circumstances of the monks who created these manuscripts.

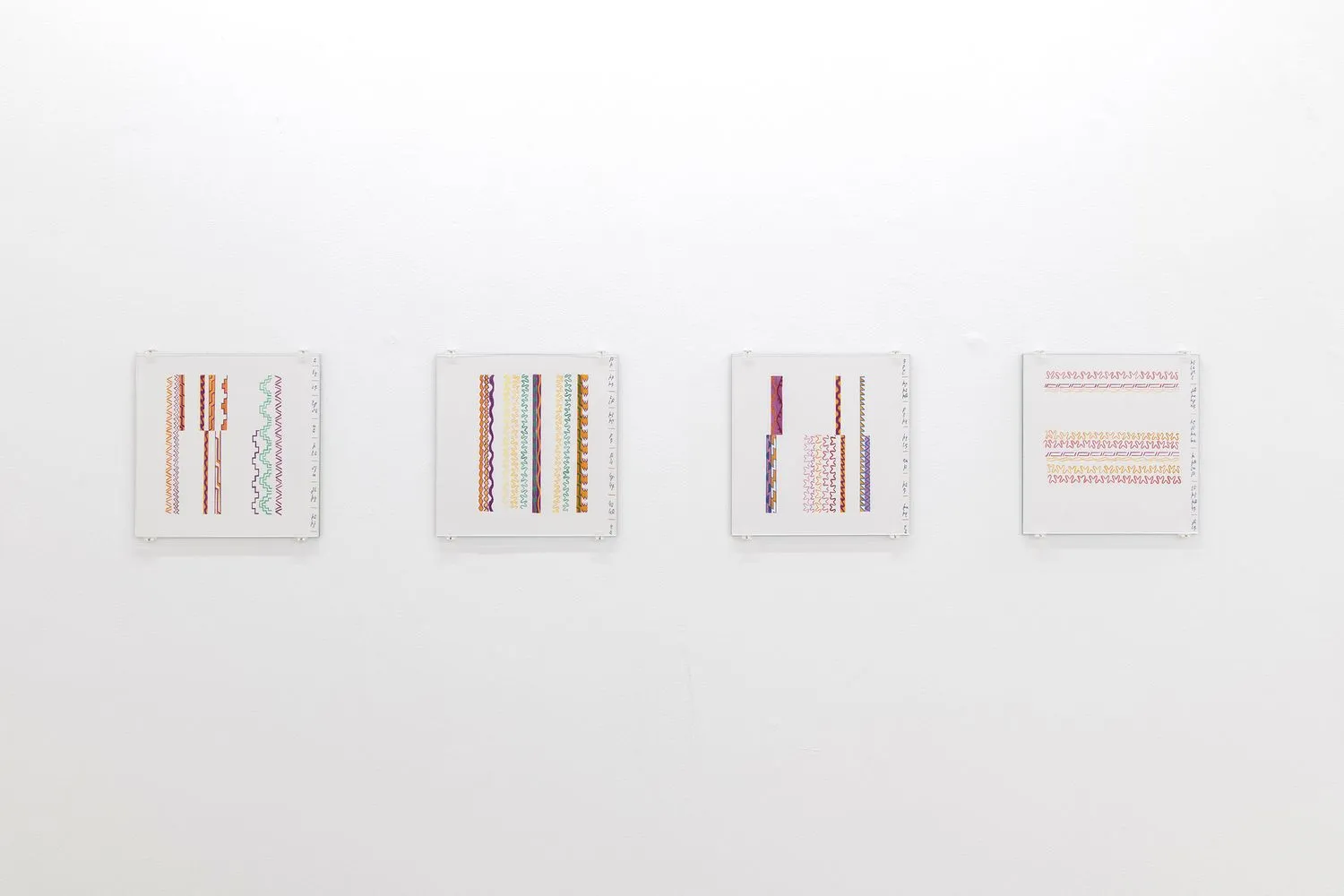

In 2023, for my solo exhibition at Baronian Gallery, I presented this series of drawings in which I was reworking and reinterpreting the decorative borders of the illuminations and rearranging their ornamental elements. In the right margin of each drawing, I copied a part of the canon tables, which are the intricate indexes of these illuminated manuscripts. The titles of each drawing, as well as the carpets, are all phrases selected from Colophons of Armenian Manuscripts, 1301-1480, A Source for Middle Eastern History by Avedis K. Sanjian, published in 1969. I have had this book for a decade, probably. The colophons are markers of the histories of dislocations, which have been a constant reality in the last two millennia of Armenian history. While making the drawings, I started re-reading the book.

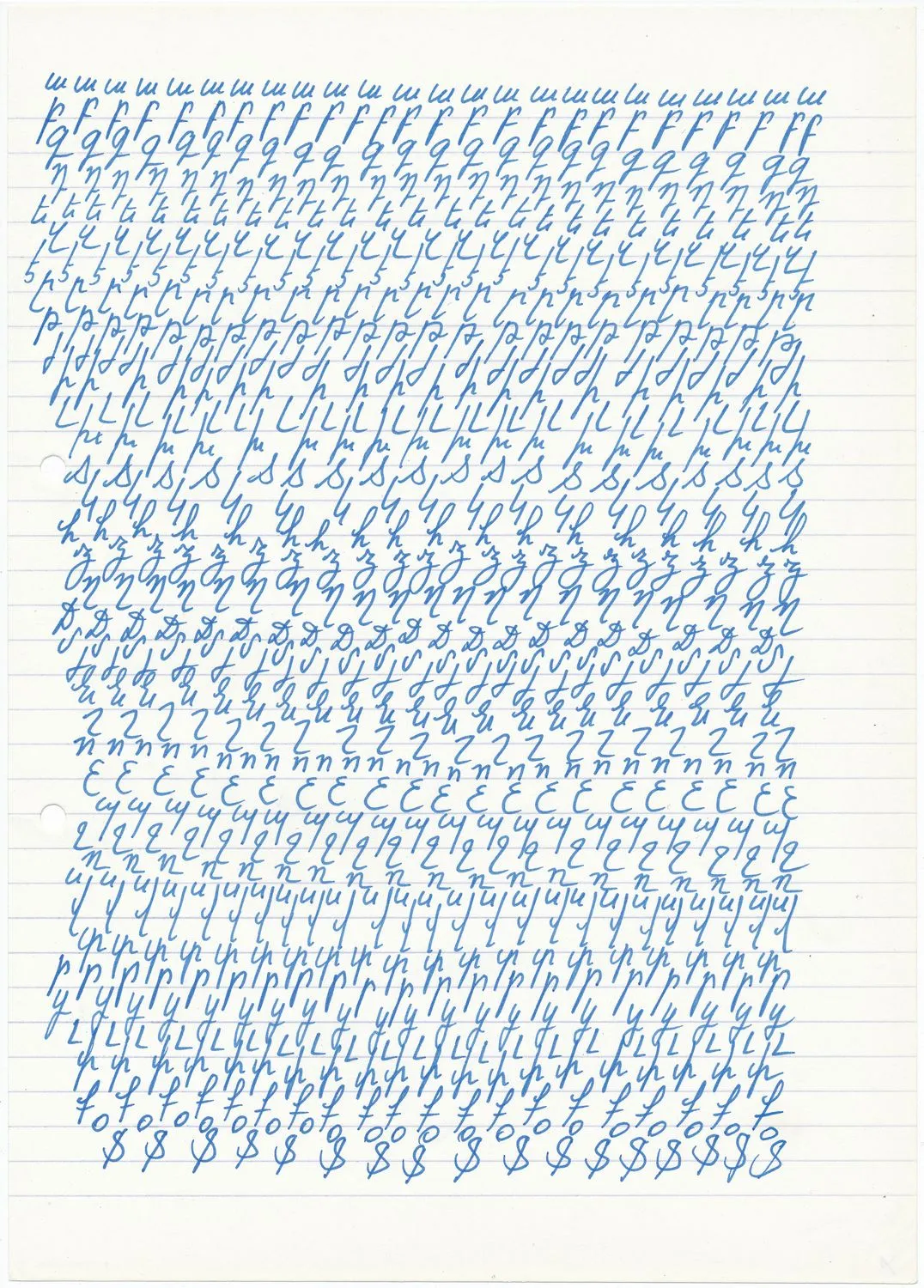

Colophons and indexes are both placed in the margins of a book and the ornaments are drawn in the margins of the religious images. In this series, I bring different kinds of margins to the centre. Language appears in the canon tables, which consist of single letters or combinations of two letters, as well as in the titles. The drawings I made are not miniatures like the originals, but they are small in size and for me already miniature work. The process of making them was fun, but also slow and meticulous work. Re-appropriating this medieval tradition and opening up graphic possibilities and combinations made me become a kind of copyist myself, reactivating the scribes' muscle memory. Appropriation, language and translation have always been at the centre of my artistic practice.

Jelena Martinović: The collaboration brings together your contemporary perspective and N. Vrouyr's long-standing expertise in carpets. How did this dialogue shape the project?

Mekhitar Garabedian: Naturally, I have been aware of the esteemed reputation of the Vrouyrs for a long time. The first carpet I had made was tufted, and while I liked the result, I was looking for something different, so I started the ongoing dialogue with the Vrouyrs. They don't just sell and produce carpets; they have, as you rightly say, a long-standing expertise which is very rare. Therefore, I feel privileged to work with them and benefit from their invaluable knowledge and advice. It is always a pleasure to visit them at their impressive showroom, which has been at this location in Antwerp since 1920, and to chat with them not only about carpets but also about current affairs of all kinds.

We share our Armenian origins, and the first carpets I made with them belonged to a series of works investigating the particular state of my mother tongue, featuring the Armenian alphabet and the transliteration of Armenian words into Latin characters. They depict the documentation of a learning moment, which is related to the disintegration of my mother tongue. One of these carpets was recently acquired by KANAL – Centre Pompidou. Last year, we collaborated on two new works drawing on the tradition of Armenian medieval manuscripts, which will be presented for the first time at BRAFA.