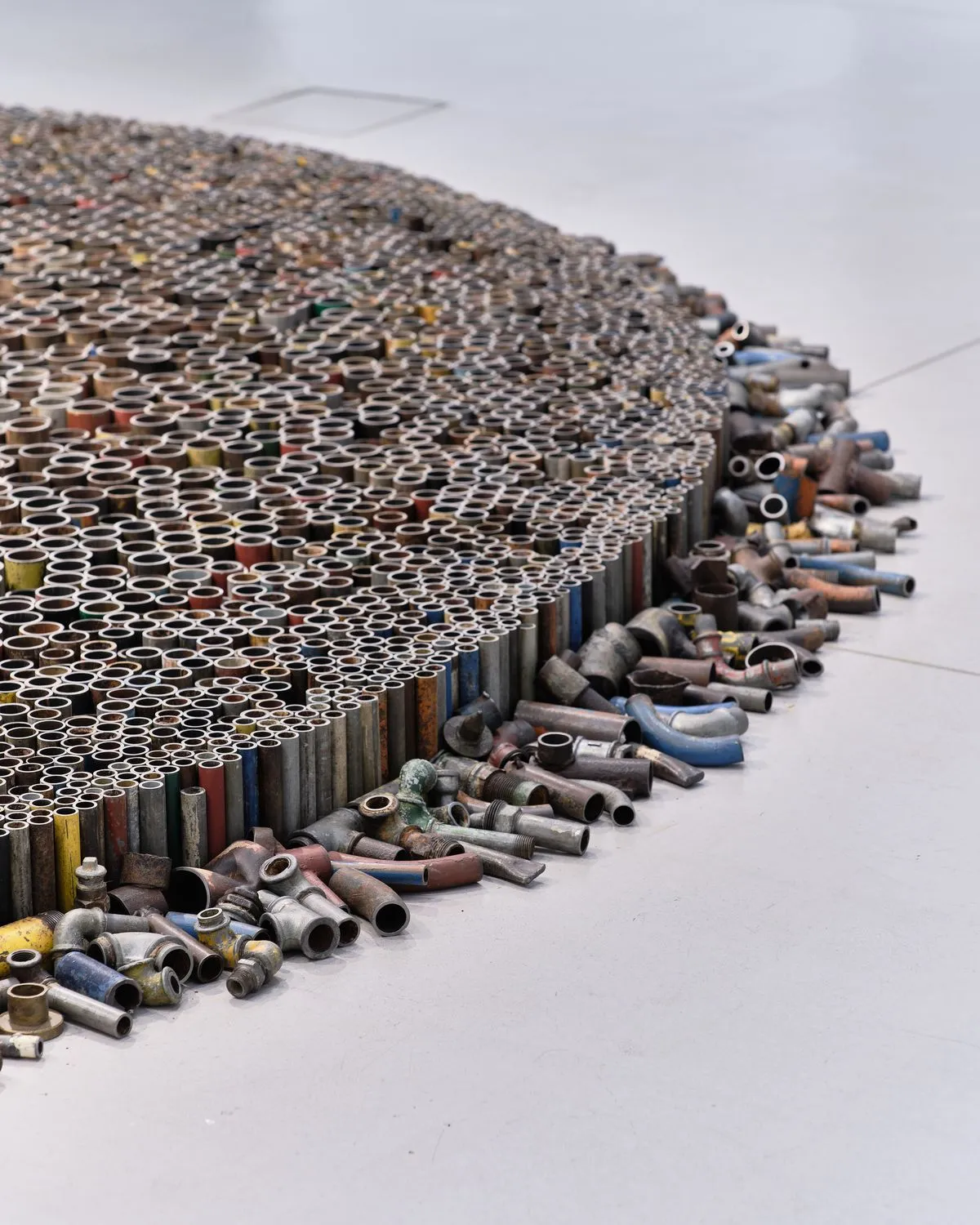

Installation view of Roman Ondak's The Day After Yesterday at Kunsthalle Praha. Photo: Vojtěch Veškrna

Installation view of Roman Ondak's The Day After Yesterday at Kunsthalle Praha. Photo: Vojtěch Veškrna Over the last thirty years, Roman Ondak has explored the rhythms of everyday life, turning familiar gestures, objects, and social routines into subtle sites of inquiry. Continuously testing and stretching the boundary between art and life, Ondak turns these situations into poetic explorations of time, memory, and identity. What might appear neutral or self-evident is revealed as a dense network of learned behaviors, social codes, and internalized norms. Rather than interrupting these systems outright, Ondak nudges them slightly out of alignment, just enough for their mechanisms to become visible. Through these shifts, he encourages careful observation of the everyday.

These concerns are brought into focus in The Day After Yesterday, Ondak's first large-scale exhibition in Central and Eastern Europe in over two decades, currently on view at Kunsthalle Praha. While the exhibition spans more than thirty years of work through a range of media, Ondak has been careful to avoid framing it as a retrospective. Arranged thematically rather than chronologically, early and recent works are placed in dialogue, emphasizing the persistence of questions that continue to shape his practice.

Drawing from his lived experience of Czechoslovakia, as well as the political transition it went through, Ondak uses this context and his biography as a lens through which to examine wider social and political frameworks. Across the exhibition, the artist employs his characteristic methodologies: the collapse of private and public space and the layering of different time registers, where political history folds into individual lives.

The work The Day After Yesterday, from which the exhibition takes its name, pairs a found snapshot of Ondak's family with a staged photograph taken at the same location, in the same clothes. By combining chance and careful orchestration, the work brings different moments into close proximity, allowing past and present to appear side by side. The title itself further underscores Ondak's playful and slightly disorienting way of thinking about time. Across the exhibition, the private continuously intersects with the public, inviting reflection on how individual experience takes on shared meaning. Works such as Sea in My Room, Freed Doorway, and Demarcation transform intimate objects, from the artist's childhood room door to his building's doorbell, into points of collective attention.

Placing familiar objects in unfamiliar conditions is a recurring strategy throughout the show. In Do Not Walk Outside This Area (2012), a detached airplane wing is laid out on the gallery floor, allowing visitors to walk across an object normally off-limits. While engaging with the piece may feel rebellious, this access is provisional. A similar condition structures Escape Circuit (2014), where a series of interconnected cages forms a closed loop with no exit. Movement is possible, even encouraged, but it never leads beyond the structure itself. Together, these works show how choice can appear available while remaining shaped by constraints, exposing freedom as something designed or simulated within existing structures. In a world marked by deepening instability, these works feel especially timely, pressing on questions of what freedom means today.

In Ondak's work, ordinary gestures are never neutral; they carry meaning. Performed by real people in real time, these modest, often banal actions extend from individual experience into the collective, revealing social and relational dimensions. In Across That Place (2008-2011), Ondak turned a simple act—skimming stones across the Panama Canal—into a moment of shared participation. Volunteers took part in a playful activity that unfolded against the canal's complex political and historical backdrop. Photographs, hand-painted posters, and other materials from the event form an installation, extending the action beyond its original moment.

Perhaps Ondak's best-known participatory work, Measuring the Universe (2007), draws from the familiar gesture of parents measuring their children. Visitors are encouraged to mark their height on the wall, creating a collective portrait over time. Unfolding only through audience involvement, the work turns into a visual representation of how individual actions help shape a larger system, raising questions about the responsibilities that come with it. Placed in a corner of the gallery, Resting Corner (1999) features a simple sofa and shelving unit—familiar furniture from socialist-era Czechoslovakia. By sitting, visitors turn an ordinary gesture into a performance, becoming part of the artwork. Those moving around the gallery are also implicated, observed by the seated participants and contributing to the relational dynamics.

Across Roman Ondak's practice, time is experienced as layered and cyclical, with past and present coexisting. The weight of political history meets individual lives, appearing as a force shaping lived experience. In Event Horizon (2016), this approach is materialized through the rings of a 130-year-old oak tree: each disc marks a year between 1917 and 2016, inscribed with an event Ondak considers significant. As different discs are displayed daily over the course of the exhibition, collective history is continuously folded into the present. A similar compression of timelines appears in Bad News Is a Thing of the Past Now (2003), which brings together two black-and-white photographs of Ondak's father and, decades later, the artist himself, seated on the same park bench reading a newspaper covering the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Ondak's interest in video and performance reflects the same concerns seen across his practice. His videos center on small, simple actions situated in everyday public space. The Stray Man follows a figure who repeatedly pauses outside a gallery window, looking in but never entering, foregrounding the act of observation and the boundary between art and daily life. Resistance records a group of people moving through an exhibition with their shoelaces untied—a minor breach of social convention that can be corrected instantly, but when shared across the group, registers as a collective gesture, resistance even.

Ondak's work trains our eye for how individuals move within the systems they inherit and help sustain. If history returns in cycles, the question is not whether bad news belongs to the past, but how we recognize its recurrence—and what it means to act within it.

The exhibition The Day After Yesterday is on view at Kunsthalle Praha in Prague, until March 9th, 2026.