Shoji Ueda, Dad, Mom and Children, 1949. Silver Gelatin Print. Courtesy Each Modern Gallery.© Shoji Ueda

Shoji Ueda, Dad, Mom and Children, 1949. Silver Gelatin Print. Courtesy Each Modern Gallery.© Shoji Ueda Japan has long been recognized as a hub for photographic innovation, with a rich history of both technical development and artistic exploration. The country's relationship with photography is distinctive, marked by a deep cultural engagement with the medium and a unique blend of traditional and modern influences. Known for its amazing Nippon publications and highly developed photo industry, Japan has one of the most innovative and distinctive photography cultures and is an excellent place to eye new talent.

Following World War II, cameras became much more affordable in the country, and with their technical characteristics improved, many more people tried their talent in photography. Soon, Japan became one of the world centres for photography with leading camera brands and photo equipment originating and developing there. Photojournalism was also on the rise in this period and many Japanese photographers took cameras to record the world around them in their work.

Between 1957 and 1972, a ground-breaking group of radically experimental photographers, which significantly contributed to 20th-century art, emerged in Japan. With the traumas of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, followed by the US occupation, Japanese photographers turned to the fast and intuitive qualities of the photographic medium to capture the nation's post-war experience. Bold in their execution, these artists, grouped in the Provoke collective, developed a new visual language that broke all the rules and created iconic images with a strong narrative thread. Although photography was on the rise, the market was still small, so photographers turned to photobooks and magazines like PROVOKE, Asahi Camera, and Camera Mainichi to circulate their work, a tradition that continues to this day.

While the field was significantly dominated by men, Japanese women photographers have also played a crucial role in shaping the country's photographic landscape. Despite facing significant societal and cultural barriers, women photographers began to make their mark in the post-war era, challenging gender norms and offering fresh perspectives on both the medium and their own experiences. Focusing on themes of identity, gender roles, and the female body, these photographers have not only expanded the narrative of Japanese photography but have also used the medium as a powerful tool for personal and social empowerment.

In 1974, a group exhibition titled New Japanese Photography opened in MoMA, which launched Japanese photography on the international scene. After MoMa, a number of solo and group retrospectives of Japanese photographers followed, which raised the profiles of these artists. The 1989 exhibition Japanese Women Photographers: From the 1950s to the 1980s at the Lehigh University Art Galleries (LUAG) in Pennsylvania also helped to highlight the contributions of women to the field, offering a broader recognition of their impact.

Below, we highlight a selection of the most influential Japanese photographers, each known for their distinctive approaches to the medium. These artists have shaped the landscape of contemporary photography with their groundbreaking work, continuing to resonate with and inspire new generations of photographers across the globe.

A self-proclaimed addict of cities, photographer Daidō Moriyama (b. 1938, Ikeda) is a pivotal figure in street photography, known for his raw, high-contrast images that capture the chaos of urban life. Emerging in 1968, Moriyama’s work delves into the chaotic undercurrents of modern life, focusing on themes of alienation, transience, and the darker aspects of urbanization. His images—a mix of grainy textures, high contrasts, and blurred compositions—reject conventional photographic aesthetics in favor of a raw, visceral immediacy.

"Chaotic everyday existence is what I think Japan is all about," he said once. "This kind of theatricality is not just a metaphor but is also, I think, our actual reality." This statement underscores his philosophy of embracing imperfection and disorder as reflections of authentic reality. His signature visual language mirrors the theatricality and fragmentation of urban life, challenging viewers to grapple with the emotional and psychological landscapes of his subjects.

Some of his best works are printed in the photo books Hunter and Farewell Photography. Moriyama's oeuvre is not just a documentation of urban life but a critique of modernity itself—its speed, its alienation, and its beauty in decay. By embracing the imperfections and ephemerality of his subjects, he redefined the possibilities of street photography, carving out a space for spontaneity and emotional resonance.

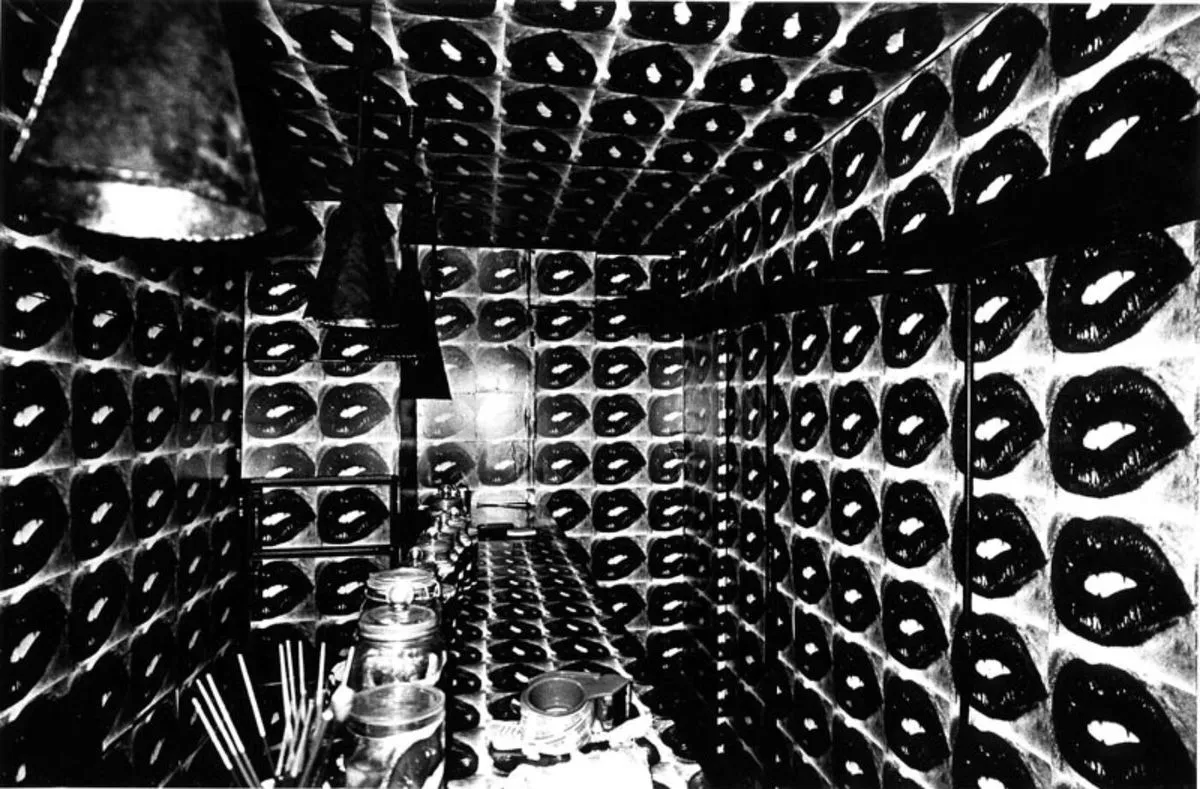

Nobuyoshi Araki (b. 1940, Tokyo) is one of the most prolific and provocative photographers, renowned for his irreverent, often controversial imagery. With around 500 photo books to his name and a daily commitment to taking photographs, Araki's work explores themes of sexuality, intimacy, and mortality. His bold approach challenges conventions, blending eroticism with humor and capturing fleeting, private moments in a raw, unapologetic manner.

Araki studied photography from 1959 to 1963 before joining the advertising agency Dentsu, where he honed his experimental style. His work often ventures into mixed media, using collage, film, and even performance to push boundaries and provoke thought. Known for his series on bondage and urban landscapes, Araki’s photography is deeply personal, reflecting his experiences, emotions, and the fluctuating rhythms of life.

His distinctive approach has made him a central figure in contemporary photography, influencing a wide range of photographers and artists. For Araki, photography is not merely an art form but a way of living, capturing both the beauty and darkness of existence.

One of Japan's most influential postwar photographers, Shōmei Tōmatsu (1930–2012) captured the complex emotional landscape of a nation in recovery. His work spans the spectrum from despair to hope, often oscillating between moments of profound darkness and bursts of light. Tōmatsu’s photographs are not just visual documents but visceral responses to the shattered world around him, reflecting the trauma of war and the societal shifts that followed.

"After the defeat, darkness and light became clearly visible and values shifted 180 degrees. . . . My most impressionable years were spent during those times, and that intense experience became a filter through which I've seen things ever since," Tōmatsu explained, highlighting the profound impact of the postwar period on his vision. His images are marked by an emotional intensity that goes beyond mere documentation, capturing the fleeting essence of a nation grappling with its identity.

Tōmatsu’s work remains a powerful meditation on the psychological and emotional scars of war, as well as the resilience of the human spirit in the face of devastation. His ability to distill the complexity of the Japanese postwar experience makes his photography a central part of the country's artistic history.

Hiroshi Sugimoto (b. 1948) is known for his conceptual photography that explores the passage of time, history, and perception. With his meticulous approach, Sugimoto uses an 8x10 large format camera and long exposures to create images that evoke a sense of timelessness and contemplation. His work spans a wide range of subjects, from natural landscapes to constructed environments, but always with a focus on the passage of time and its effects on human experience.

His major series include Dioramas, where he captures museum displays with painterly precision; Theaters, which depict empty movie theaters with ghostly, long-exposure effects; and Seascapes, which offer serene, vast ocean views as meditations on infinity. Other works, such as Portraits and Architecture, explore light, shadow, and abstraction.

Sugimoto's work continuously invites viewers to question their perception of time and reality, often revealing the ephemeral nature of both. His contribution to contemporary photography is immense, with his iconic images appearing in major collections worldwide. One of his photographs even graced the cover of U2's No Line on the Horizon, a testament to his influence beyond the art world.

Ishiuchi Miyako (b. 1947, Japan) is renowned for her deeply introspective and often provocative approach to photography. Her work explores the intersections of memory, identity, and the human body, offering poignant reflections on trauma, aging, and the passage of time. Ishiuchi's series 1•9•4•7 (1988–1989) is particularly significant, where she focused on the bodies of women born in the same year as herself, capturing intimate details that speak to the lives of women navigating aging and societal expectations.

Ishiuchi's work often addresses themes of loss and resilience, particularly in her haunting photos of Hiroshima survivors’ scars and her documentation of personal objects left behind by the victims of the Fukushima disaster. Her ability to capture vulnerability with both tenderness and strength has earned her international acclaim, positioning her as one of Japan’s most important contemporary photographers. Through her lens, Ishiuchi delves into the layered complexities of identity, memory, and the body.

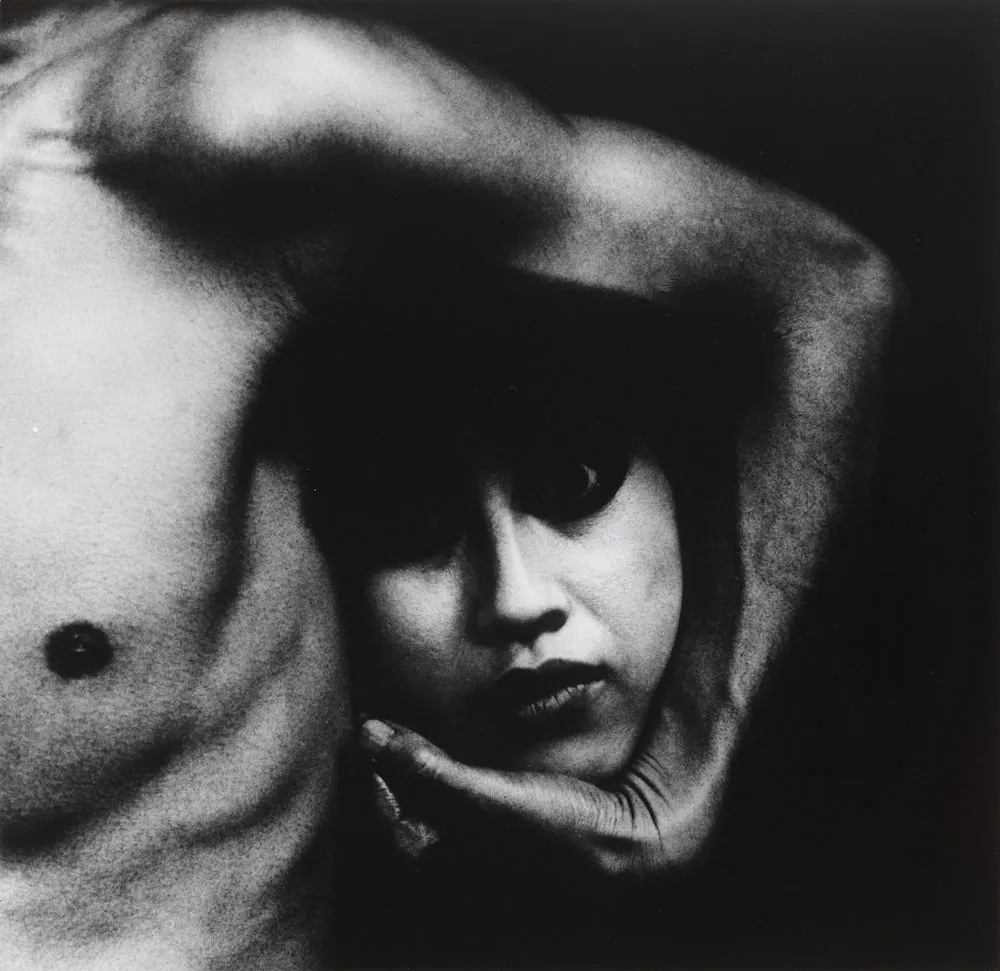

Another pivotal figure in postwar Japanese photography, Eikoh Hosoe (b. 1933, Yonezawa) is known for his bold, theatrical images that explore the complex intersection of tradition and modernity. His most famous work, Killed by Roses, produced at the invitation of writer Yukio Mishima, features intensely dramatic portraits that blend symbolism, sexuality, and mysticism. These images remain iconic within the medium, showcasing Hosoe’s unique approach to visual storytelling.

Throughout his career, Hosoe sought to expand the boundaries of photography, not only through his own work but by fostering international ties and contributing to the global photography community. He organized numerous workshops and sought to bridge cultural gaps, helping to establish Japanese photography as a force on the world stage.

Hosoe's work, marked by its theatrical and often excessive style, remains a powerful reflection of the contradictions and complexities of postwar Japan.

Issei Suda (1940–2019) made a bold decision to leave Tokyo University in order to pursue his passion for photography, enrolling at the Tokyo College of Photography in 1961. His immersion in the cultural landscape of Japan deepened when he became the cameraman for the theatrical group Tenjō Sajiki, a role that connected him to the vibrant artistic movements of the time. Suda’s sharp, investigative eye allowed him to capture the stark contrasts between Japan’s deeply rooted traditional customs and the swift social transformations following World War II.

While the postwar Japanese photographic scene was dominated by two major movements—the reality-focused Kompora group and the radical, confrontational Provoke collective—Suda remained independent. He carved out his own approach, refusing to align himself with either camp.

As he stated, "The most difficult thing for me is to work with other people. So, I worked for them as an outsider." This outsider perspective became a cornerstone of his work, allowing him to remain free from artistic constraints and explore the subtleties of a rapidly changing nation. Suda’s photographs are imbued with quiet observation, capturing fleeting moments that convey the complexity and tension of a society in flux. His work continues to stand as a deeply personal and evocative exploration of Japan’s postwar identity.

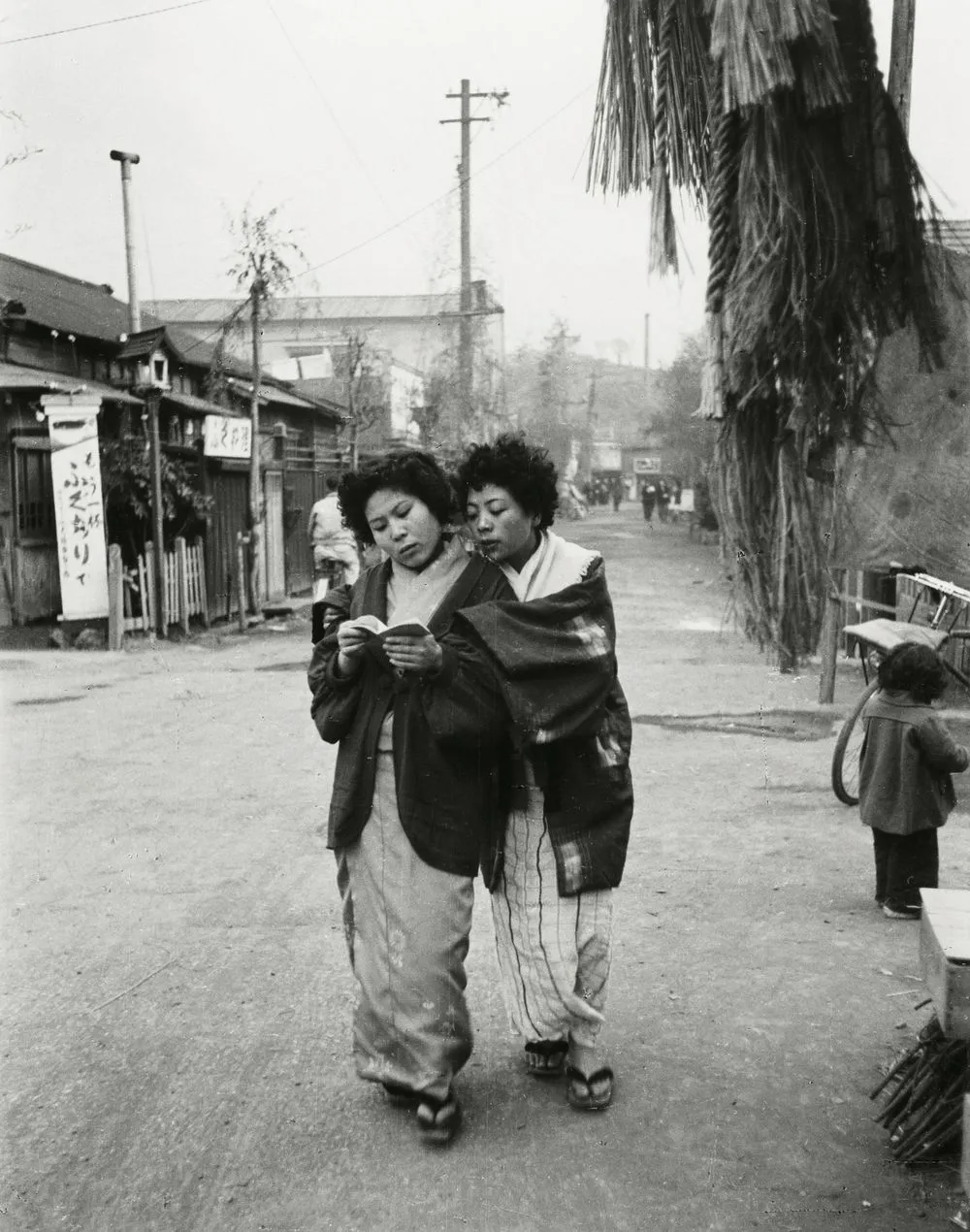

Tokiwa Toyoko (1945-2019) is celebrated for her bold exploration of femininity and sexuality in postwar Japan, particularly in her depictions of women living near American military bases. Tokiwa's photographs capture the raw, unfiltered realities of women's lives, often focusing on marginalized groups such as sex workers and bar hostesses, offering a rare and unflinching look at Japan’s societal undercurrents during the American occupation. Her work challenges the objectification of women’s bodies, providing an important counter-narrative to the eroticized depictions popularized by male photographers of the time.

Tokiwa's unrelenting focus on the lives of women in a rapidly changing Japan provides a nuanced commentary on both gender roles and the socio-political shifts of the postwar era. Her images remain a vital part of the conversation around the role of women in photography, offering a critical lens through which to view the complexities of identity, sexual autonomy, and the intersection of politics and personal life.

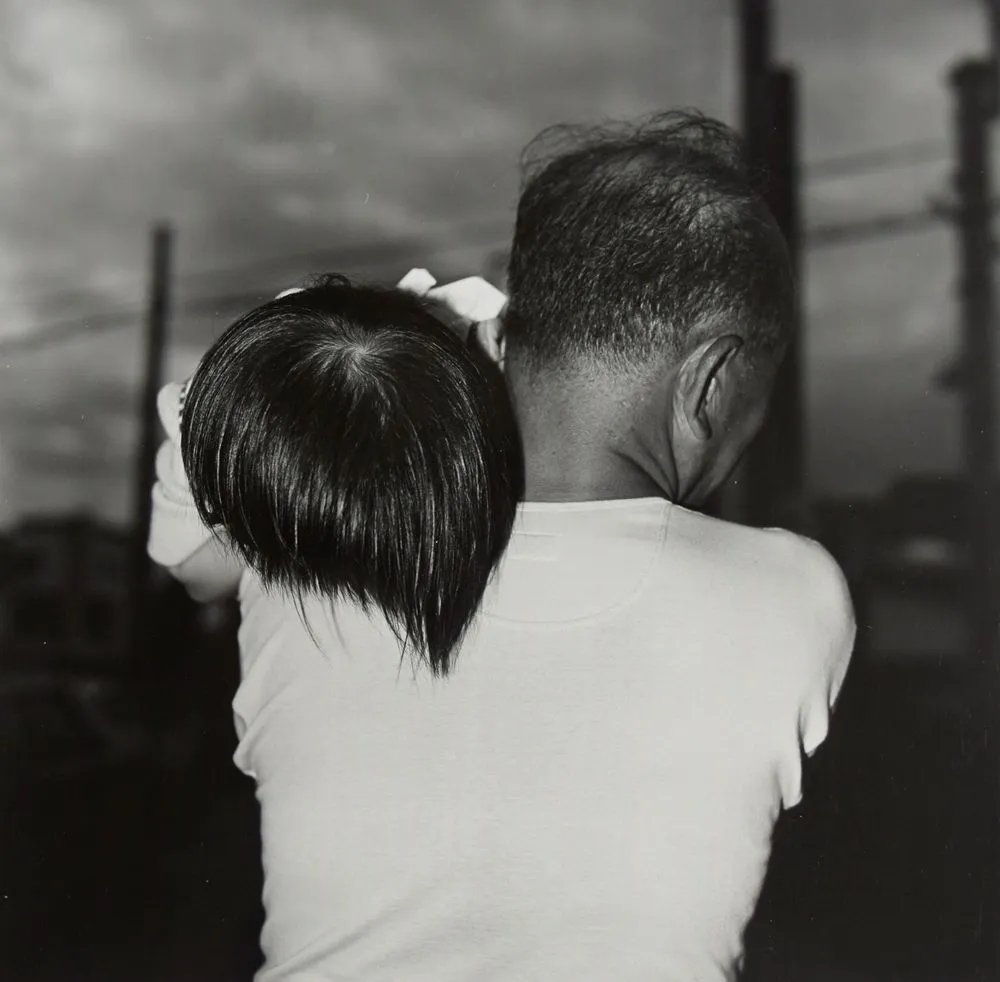

Shōji Ueda (1913–2000) is celebrated for his playful yet meticulous photography, which often captures surreal and dreamlike landscapes set against the backdrop of the Tottori Sand Dunes. Born and raised in Tottori, Ueda developed an early interest in photography, receiving his first camera in 1929. He later moved to Tokyo, where he trained in photography at the Mimatsu Department Store photo studio. After returning to Tottori, he opened his own photo studio, where his distinctive photographic style began to take shape.

Ueda’s work stands apart from the realist documentary photography of his peers, as he embraced free compositions and surrealist elements. His photographs often evoke a sense of whimsy and fantasy, merging the natural world with imaginative, sometimes fantastical scenarios. Through his unique approach, Ueda created images that were not just representations of reality but explorations of the boundaries between the real and the imagined, reflecting his deeply personal and unconventional worldview.

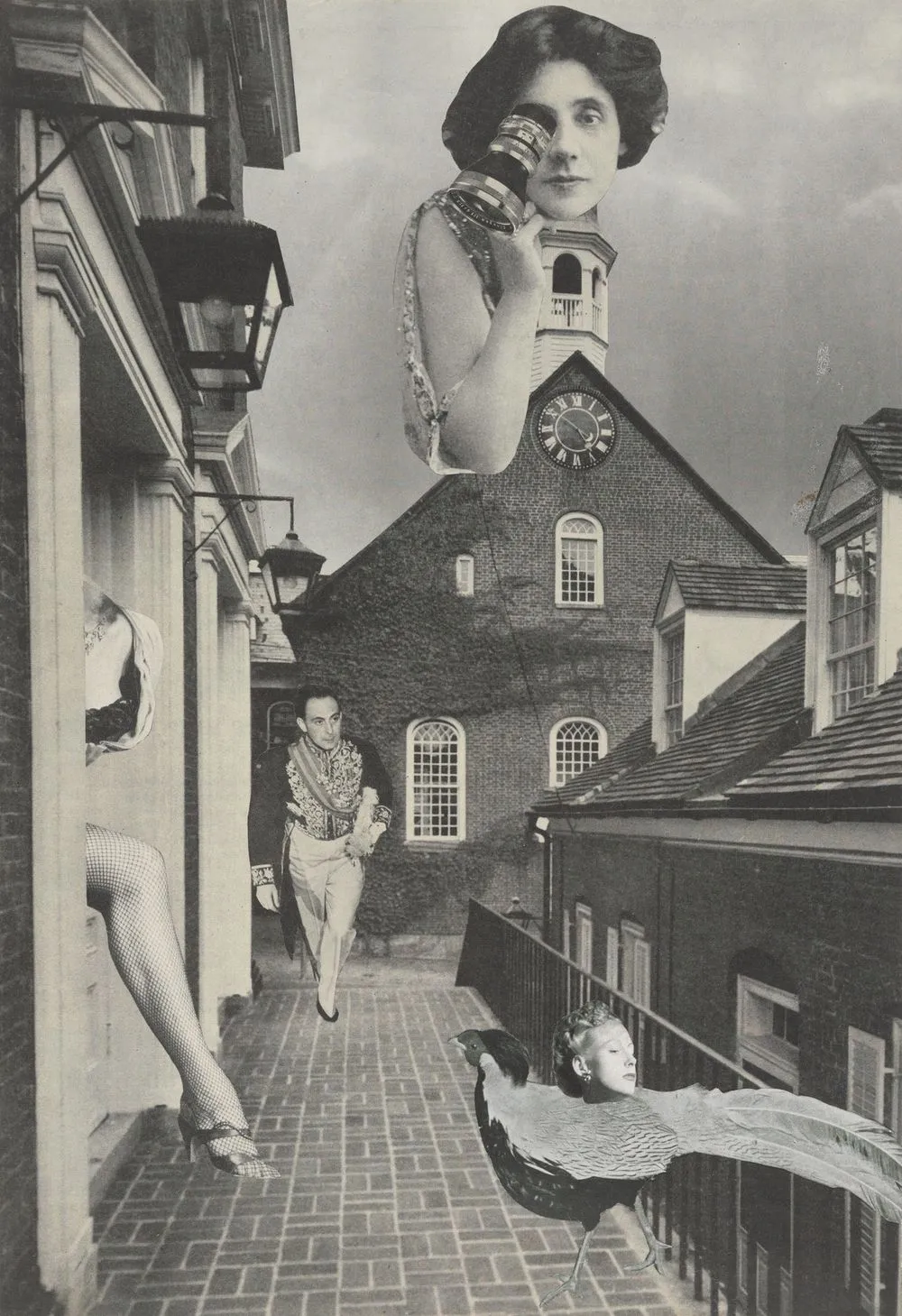

Okanoue Toshiko (b. 1936, Japan) is a pioneering figure in Japanese photography, known for her innovative use of collage and surrealistic imagery to explore themes of femininity, identity, and the body. Her unique approach blends traditional Japanese art forms with photographic techniques, creating striking, multilayered compositions that challenge conventional notions of beauty and gender. Okanoue's work often draws on the concept of hari-e, a Japanese art of cutting and assembling paper, which she incorporates into her photographs to create dreamlike, otherworldly images.

Her surrealist collages, which often feature fragmented female bodies and symbolic elements, present femininity as a strength rather than a weakness. Okanoue's work remains influential, not only within Japan but also in global Surrealist movements, where her contributions continue to resonate with artists and photographers exploring the boundaries of gender and identity.

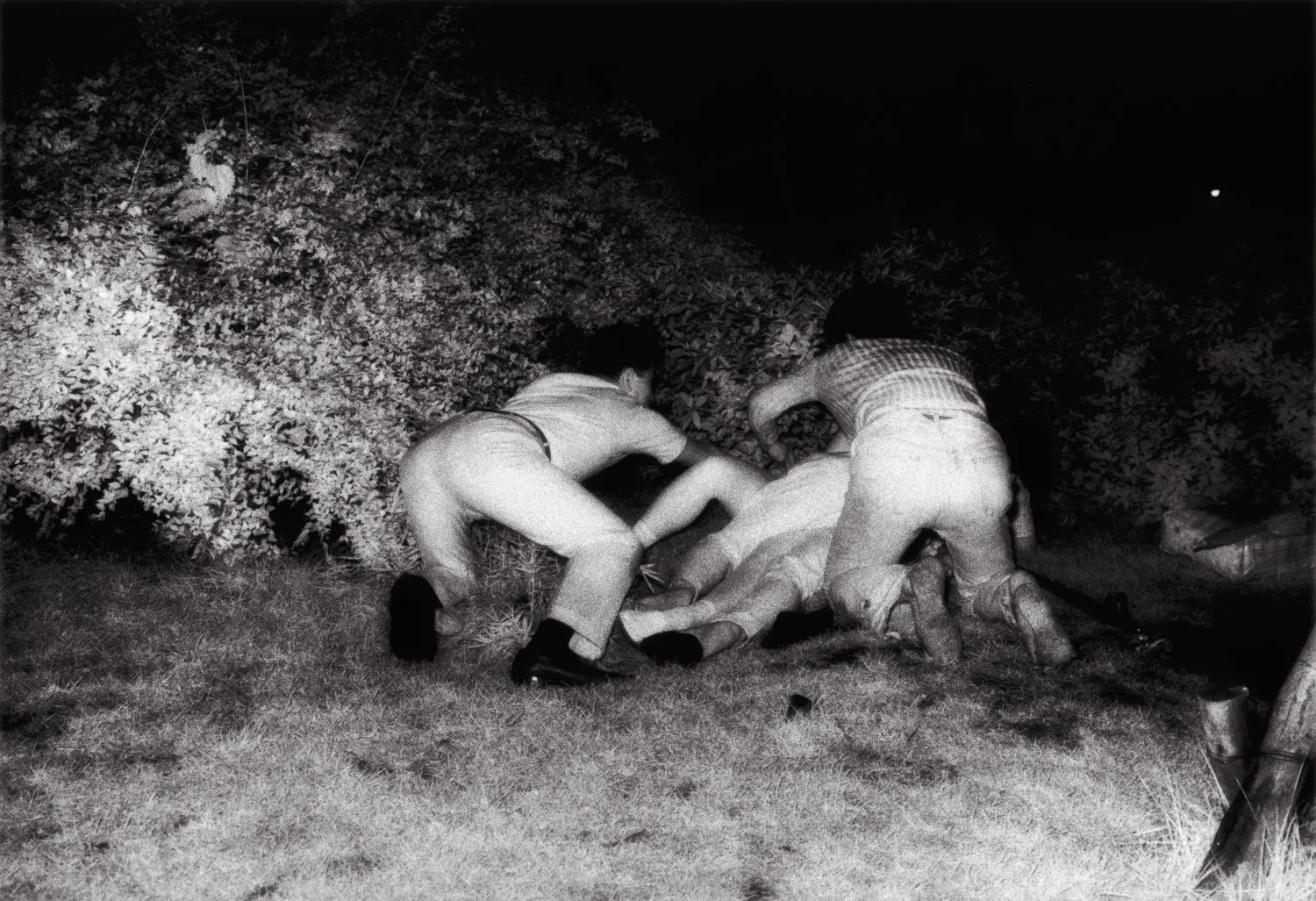

Kohei Yoshiyuki (1946-2022) is best known for his provocative series The Park, in which he captured intimate, often clandestine moments of couples engaging in sexual activity in Tokyo’s public parks during the 1970s. Yoshiyuki's images, taken with a night-vision camera, blur the line between voyeurism and documentation, exploring the tension between public and private spaces. His work challenges societal norms, focusing on the hidden lives of individuals in urban settings, and reflects the complexities of human desire and the act of observation.

Yoshiyuki's approach is deeply influenced by his interest in the dynamics of secrecy and exposure, capturing moments that are both personal and invasive. His photographs, while confronting, invite the viewer to reflect on the nature of privacy, the boundaries of consent, and the power dynamics involved in the act of looking. The stark lighting and grainy texture of the images heighten the sense of voyeurism, while also giving them an almost clinical distance. Through The Park, Yoshiyuki’s work became a critical commentary on the way modern society navigates the tension between personal freedom and public surveillance.

Watanabe Hitomi (b. 1939, Japan) is renowned for her powerful photographs that document speeches, state violence, and the aftermath of social unrest. Her work captures the raw emotional intensity of political moments, highlighting the tension between authority and resistance. Through her lens, Watanabe portrays the human cost of power struggles, focusing on both the immediate impacts of violent events and the lingering consequences in their wake.

Her photography is a profound commentary on the intersection of politics, memory, and society. With a keen eye for detail and a sensitivity to the emotional undertones of public demonstrations, her images provide a poignant reflection on the enduring effects of state violence and civil disobedience. Watanabe's work remains a significant contribution to contemporary Japanese photography, offering a critical lens on the complexities of historical and political narratives.